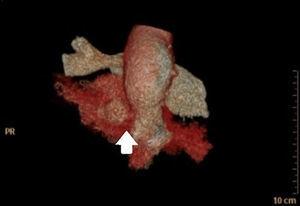

In this issue of Medicina Intensiva, García-Gigorro et al.1 analyze mortality and its potential related factors in cardiogenic shock patients requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for stabilization or recovery in a third-level hospital with a heart transplant program. Despite the limited strength of the results of the study, the article underscores that the use of cardiopulmonary assist devices, and particularly ECMO, is a reality in the management of patients with severe heart failure, and introduces a substantial change in their evolution and prognosis.

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in its different variants, i.e., veno-arterial (VA) and veno-venous (VV), is a total or partial cardiopulmonary assist system that was first used for therapeutic purposes more than 40 years ago.2 Over the decades the technique has been characterized by both advantages and drawbacks, though with the development of more compact devices and the introduction of biocompatible materials, its use has become widespread throughout the world – particularly in the early XXI century, thanks to the studies of the University of Michigan and subsequently the CESAR study,3 and the series derived from the influenza A epidemic.4 Since its creation in 1989, almost 80,000 patients have been included in the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) registry, and the current decade is clearly the time when the use of ECMO in adults has grown exponentially.5

The importance of ECMO is also reflected in both the growing number of publications on the technique (from 231 in 2005 to 1062 in 2016) and the ongoing lines of research in this field (128 studies in ClinicTrials). However, despite numerous studies with data favorable to the use of ECMO in critical patients with severe respiratory or heart failure, in which conventional management has failed, there is still not enough scientific evidence to establish a clear indication of the technique in these disease scenarios.6 Few studies have been made in Spain to date, and the existing publications are limited to several critical patient series7 and a single national registry8 with the implantation of 117 ECMO systems between 2007 and 2010, in 15 national centers.

The study of García-Gigorro et al. shows the mortality rate among cardiogenic shock patients requiring VA ECMO to be high (close to 40%), and this rate moreover increases significantly depending on the indication and severity of the patient condition (SAPS II score) at the time of implantation of the technique. These data are comparable to those of other series,9 and have resulted in prognostic scales of great use in assessing survival among cardiogenic shock patients amenable to management with devices of this kind.10

On the other hand, ECMO has been associated to frequent complications and high morbidity, despite relatively good survival among those patients in which the device has been successfully withdrawn. These results remind us of the recommendations of the ELSO when dealing with patients with severe respiratory or heart failure who need ECMO to survive. In effect, the mentioned guidelines underscore the need to take into account that successful assist is conditioned to a series of factors, such as the availability of a device suited to the disease condition and management objective, optimum timing of implantation of the device, an adequate implantation technique, and correct post-implantation management – with special emphasis on the prevention and treatment of possible complications, in order to reduce the high morbidity-mortality of these patients as far as possible.

Although the present study has few patients, and its single-center design limits the drawing of firm conclusions, it describes a series of critical patients subjected to VA ECMO that are very representative of the real-life situation in our setting, with findings similar to those published in other countries, and which paves the way to continue investigating in this area of Intensive Care Medicine.

If we believe the notion that “the species that survives is not the strongest or the most intelligent, but the one most receptive to change”, then the use of ECMO very probably will represent one of the substantial changes in the management of critical patients over the coming years. Nevertheless, both the complexity of implantation and the great material and human resources required make it essential for such change to be structured and integrated within a multidisciplinary strategy aimed at ensuring quality care for patients with severe cardiorespiratory failure.

Please cite this article as: Martin-Villen L, Martin-Bermudez R. ECMO: pasado, presente y futuro del paciente crítico. Med Intensiva. 2017;41:511–512.