Survivin is a member of inhibitors of apoptosis proteins family. There are not data about the association between mortality of septic patients and blood survivin concentrations. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine whether exist that association.

DesignObservational and prospective study.

SettingThree Spanish Intensive Care Units.

PatientsPatients with sepsis or septic shock according to Sepsis-3 Consensus criteria.

InterventionsSerum survivin concentrations were determined at moment of sepsis diagnosis.

Main variable of interestMortality at 30 days.

ResultsA total of 204 patients were included in the study, of which 75 (36.8%) died in the first 30 days. Lower age (p<0.001), serum lactic acid levels (p=0.001), rate of septic shock (p=0.001) and SOFA (p<0.001), and higher serum survivin levels (p=0.001) exhibited surviving (n=129) than non-surviving patients (n=75). We found in multiple logistic regression analysis an association between serum survivin concentrations and mortality independently of SOFA, lactic acid, age, INR, activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and empiric antimicrobial treatment adequate (OR=0.968; 95% CI=0.946–0.990; p=0.005), and also independently of APACHE-II, lactic acid, platelet, INR, aPTT and empiric antimicrobial treatment adequate (OR=0.966; 95% CI=0.943–0.989; p=0.004).

ConclusionsThere is an association between septic patient mortality and low blood survivin concentrations.

Survivina es un miembro de la familia de proteínas inhibidoras de apoptosis. No existen datos sobre la asociación entre la mortalidad de los pacientes sépticos y las concentraciones de survivina en sangre. Por tanto, el objetivo de este estudio fue determinar si existe esa asociación.

DiseñoEstudio observacional y prospectivo.

ÁmbitoTres Unidades de Cuidados Intensivos españolas.

PacientesPacientes con sepsis o shock séptico según criterios del Consenso Sepsis-3.

IntervencionesSe determinaron las concentraciones séricas de survivina en el momento del diagnóstico de la sepsis.

Variable de interés principalMortalidad a los 30 días.

ResultadosUn total de 204 pacientes se incluyeron en el estudio, 75 (36,8%) de los cuales fallecieron en los primeros 30 días. Menor edad (p<0,001), niveles séricos de ácido láctico (p=0,001), tasa de shock séptico (p=0,001) y SOFA (p<0,001), y mayores niveles de survivina en suero (p=0,001) exhibieron los pacientes supervivientes (n=129) en comparación con los fallecidos (n=75). El análisis de regresión logística múltiple mostró una asociación entre las concentraciones séricas de survivina y la mortalidad independientemente del SOFA, ácido láctico, edad, INR, tiempo de tromboplastina parcial activada (aPTT) y tratamiento antimicrobiano empírico adecuado (OR=0,968; IC 95%=0,946-0,990; p=0,005), y también independientemente del APACHE-II, ácido láctico, plaquetas, INR, aPTT y tratamiento antimicrobiano empírico adecuado (OR=0,966; IC 95%=0,943-0,989; p=0,004).

ConclusionesExiste una asociación entre la mortalidad de los pacientes sépticos y las concentraciones bajas de survivina en sangre.

Sepsis produces a great consumption of healthcare resources and many deaths yearly.1,2 Apoptosis is one of pathophysiological pathways that are activated in sepsis.3,4 The programmed and actively cell death by apoptosis occurs in different physiological processes (morphogenesis and tissue remodelling).3,4 In addition, an increase of apoptosis occurs in different diseases such as sepsis.3,4

The main pathways of activation of apoptosis are by death receptor activation (extrinsic pathway) and by mitochondrial cytochrome-c (intrinsic pathway).3,4 Different causes could activate the intrinsic apoptosis pathway as genetic mutations, pro-inflammatory cytokines or oxidative stress. All those factors could open the mitochondrial transition pores, therefore allowing the exit of cytochrome-c from mitochondria to cytosol. Afterwards the bind between cytochrome-c, procaspase-9 and apoptotic protease activating factor (Apaf)-1 led to apoptosomes formation. Then those apoptosomes produce caspase-9 activation, which will produce caspase-3 activation (leading to cellular death due to apoptosis).3,4 However, there is a family of inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (IAPs), among which is survivin, that inhibit the activation of caspase-9 and therefore the apoptosis.5

There is few and contradictory data about blood survivin concentrations in septic patients.6,7 In one study higher serum survivin concentrations in septic patients than in healthy controls and in non-survivor than in survivor septic patients have been found, and multivariate logistic regression was not performed to determine whether serum survivin levels is an independent factor associated with mortality.6 However, in other study were found lower serum survivin concentrations in septic patients than in healthy controls and in non-survivor than in survivor septic patients, although multivariate logistic regression revealed that serum survivin levels was not an independent predictive factor for 28-day mortality.7 Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine whether exist an association between serum survivin levels and mortality of septic patients.

Material and methodsDesign and subjectsSeptic patients admitted in Intensive Care Units from three Spanish hospitals (Hospital General de La Palma, Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora Candelaria and Hospital Universitario de Canarias) were recruited during 2017 in this observational and prospective study. The approval of the Ethic Committee from all hospitals and the signed consent from some member of the patient's family were obtained.

Sepsis-3 Consensus criteria was used to stablish the sepsis diagnosis.8 We excluded those patients with steroid therapy, radiation therapy, immunosuppressive therapy, white blood cell count <1000/μl, hematological tumor, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), solid tumor, age<18 years or pregnancy.

We registered sex, age, history of ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic renal failure and diabetes mellitus of each patient. Besides, pressure arterial of oxygen, fraction inspired of oxygen, site of infection, bilirubin, lactic acid, creatinine, the presence of septic shock, activated partial thromboplastin time, platelets, international normalized ratio, leukocytes, the presence of bloodstream infection, Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment [SOFA] score,9 Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE)-II score,10 and 30-day mortality were registered.

Serum survivin concentration assaysWe frozen at −80°C samples of serum taken at moment of sepsis diagnosis. We determined serum survivin concentrations in all samples at the same time using the Human Survivin ELISA Kit (Elabscience, Houston, Texas, United States), which had intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation<10% and detection limit of 31pg/mL.

Statistical methodsCategorical variables were described as frequencies (percentages) and compared by chi-square test. Continuous variables were described as means (standard deviation) and compared by Student T-test. We compared receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of serum survivin concentrations, SOFA and APACHE-II to predict 30-day mortality using the method of DeLong et al.11 We performed multiple logistic regression analyses to determine whether there was an association between mortality and serum survivin concentrations controlling for other potential confounding variables. We included those variables showing statistically significant differences in the comparison between survivor and non-survivor patients, and also empiric antimicrobial treatment adequate (due to that it has been associated with mortality). We performed 2 regression models including different severity scores, in one including SOFA and in other including APACHE-II. In the first model, we included serum survivin concentrations, SOFA, lactic acid, age, INR, aPTT and empiric antimicrobial treatment adequate. In the second model, we included serum survivin concentrations, APACHE-II, lactic acid, platelet, INR, aPTT and empiric antimicrobial treatment adequate. In the first model, platelet was not included due to that platelet is one variable of SOFA. In the second model, age was not included due to that age is one variable of APACHE-II. Septic shock was not included in any of regression models due to that it is one variable of SOFA and APACHE-II. Kaplan–Meier 30-day survival curves with serum survivin levels lower and higher than 56.5pg/mL (cut-off selected by Youden J index) were constructed. The possible association between serum levels of survivin with creatinine levels or with bilirubin levels was analyzed by Spearman's rank correlation coefficient. We used p<0.05 cut-off to establish a difference as statistically significant, and the statistic programs NCSS 2000 (Kaysville, Utah) and SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) to perform the analyses.

ResultsA total of 204 patients were included in the study, of which 75 (36.8%) died in the first 30 days and 129 (63.2%) remained alive at 30 days. Lower age (p<0.001), serum lactic acid levels (p=0.001), INR (p=0.03), rate of septic shock (p=0.001), aPTT (p=0.02), APACHE-II (p<0.001) and SOFA (p<0.001), and higher platelet count (p=0.01) and serum survivin levels (p=0.001) exhibited surviving (n=129) than non-surviving patients (n=75) (Table 1). There were no found differences in mortality rate according to receive simvastatin previously to sepsis diagnosis or not, and any patients received simvastatin during ICU stay.

Clinical characteristics of non-surviving and surviving septic patients.

| Non-surviving(n=75) | Surviving(n=129) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex female – n (%) | 26 (34.7) | 44 (34.1) | 0.99 |

| Age (years) – mean (SD) | 63 (14) | 55 (15) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus – n (%) | 28 (37.3) | 37 (28.7) | 0.22 |

| Chronic renal failure – n (%) | 6 (8.0) | 7 (5.4) | 0.56 |

| COPD – n (%) | 12 (16.0) | 14 (10.9) | 0.29 |

| Ischemic heart disease – n (%) | 5 (6.7) | 11 (8.5) | 0.79 |

| Simvastatin previously to sepsis diagnosis – n (%) | 8 (10.7) | 17 (13.2) | 0.66 |

| Microorganism responsibles | |||

| Unknown – n (%) | 41 (54.7) | 68 (52.7) | 0.88 |

| Gram-positive – n (%) | 19 (25.3) | 29 (22.5) | 0.73 |

| Gram-negative – n (%) | 14 (18.7) | 31 (24.0) | 0.48 |

| Fungii- n (%) | 3 (4.0) | 4 (3.1) | 0.71 |

| Anaerobe – n (%) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (0.8) | 0.99 |

| Infection site | 0.68 | ||

| Respiratory – n (%) | 46 (61.3) | 75 (58.1) | |

| Abdominal – n (%) | 17 (22.7) | 33 (25.6) | |

| Neurological | 0 | 3 (2.3) | |

| Urinary – n (%) | 4 (5.3) | 7 (5.4) | |

| Skin – n (%) | 3 (4.0) | 6 (4.7) | |

| Endocarditis – n (%) | 4 (5.3) | 5 (3.9) | |

| Osteomyelitis – n (%) | 1 (1.3) | 0 | |

| Empiric antimicrobial treatment adequate | 0.80 | ||

| Unknown due to negative cultures – n (%) | 68 (52.7) | 41 (54.7) | |

| Adequate- n (%) | 53 (41.1) | 27 (36.0) | |

| Inadequate- n (%) | 3 (2.3) | 3 (4.0) | |

| Unknown due to antigenuria diagnosis – n (%) | 5 (3.9) | 4 (5.3) | |

| Septic shock – n (%) | 50 (66.7) | 55 (42.6) | 0.001 |

| Bloodstream infection – n (%) | 10 (13.3) | 21 (16.3) | 0.69 |

| PaO2/FIO2ratio – mean (SD) | 186 (110) | 200 (113) | 0.42 |

| Leukocytes (cells/mm3) – mean (SD) | 14907 (9903) | 14825 (8301) | 0.95 |

| Lactic acid (mmol/L) – mean (SD) | 4.31 (3.86) | 2.56 (2.26) | 0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) – mean (SD) | 1.94 (1.28) | 1.61 (1.27) | 0.10 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dl) – mean (SD) | 1.65 (2.03) | 1.57 (2.38) | 0.80 |

| Platelets (cells/mm3) – mean (SD) | 159907 (125722) | 221960 (173015) | 0.01 |

| INR – mean (SD) | 1.74 (1.08) | 1.43 (0.71) | 0.03 |

| aPTT (seconds) – mean (SD) | 43 (25) | 35 (12) | 0.02 |

| SOFA score (points) – mean (SD) | 12 (4) | 9 (4) | <0.001 |

| APACHE-II score (points) – mean (SD) | 24 (7) | 19 (7) | <0.001 |

| Survivin (pg/mL) – mean (SD) | 40 (13) | 58 (59) | 0.001 |

COPD=Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; PaO2/FIO2=pressure of arterial oxygen/fraction inspired oxygen; INR=International normalized ratio; aPTT=Activated partial thromboplastin time; SOFA=Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment; APACHE=Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation.

We found in multiple logistic regression analysis an association between low serum survivin concentrations and mortality independently of SOFA, lactic acid, age, INR, aPTT and empiric antimicrobial treatment adequate (OR=0.968; 95% CI=0.946–0.990; p=0.005)(Table 2). Also we found an association between low serum survivin concentrations and mortality independently of APACHE-II, lactic acid, platelet, INR, aPTT and empiric antimicrobial treatment adequate (OR=0.966; 95% CI=0.943–0.989; p=0.004).

Multiple logistic regression analyses to predict mortality at 30 days.

| Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First model | |||

| SOFA (points) | 1.158 | 1.047–1.282 | 0.004 |

| Serum survivin concentrations (pg/mL) | 0.968 | 0.946–0.990 | 0.005 |

| Lactic acid (mmol/L) | 1.095 | 0.962–1.246 | 0.17 |

| Age (years) | 1.033 | 1.008–1.059 | 0.01 |

| INR | 0.966 | 0.606–1.542 | 0.89 |

| aPTT (seconds) | 1.022 | 0.992–1.052 | 0.16 |

| Empiric antimicrobial treatment adequate (yes vs non) | 0.819 | 0.414–1.622 | 0.57 |

| Second model | |||

| APACHE-II (points) | 1.098 | 1.043–1.157 | <0.001 |

| Serum survivin concentrations (pg/mL) | 0.966 | 0.943–0.989 | 0.004 |

| Lactic acid (mmol/L) | 1.091 | 0.959–1.242 | 0.19 |

| Platelet (each 1000/mm3) | 0.998 | 0.995–1.001 | 0.12 |

| INR | 0.984 | 0.611–1.585 | 0.95 |

| aPTT (seconds) | 1.025 | 0.997–1.055 | 0.08 |

| Empiric antimicrobial treatment adequate (yes vs non) | 0.874 | 0.439–1.740 | 0.70 |

SOFA=Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment; INR=International normalized ratio; aPTT=Activated partial thromboplastin time; APACHE=Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; INR = International normalized ratio.

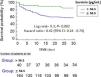

We found that the area under the curve for mortality prediction by serum survivin concentrations was 60% (95% CI=52–66%; p=0.03) (Fig. 1), by SOFA was 67% (95% CI=60–74%; p<0.001), and by APACHE-II score was 71% (95% CI=64–77%; p<0.001). There were no significant differences in the comparison of area under the curve of serum survivin concentrations and SOFA (p=0.20), od serum survivin concentrations and APACHE-II score (p=0.05), and of SOFA and APACHE-II (p=0.32).

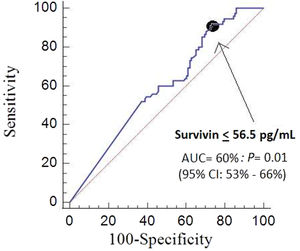

We found in Kaplan–Meier analysis lower mortality rate (Hazard ratio=0.42; 95% CI=0.24–0.74; p=0.002) in patients with serum survivin levels higher to 56.5pg/mL (Fig. 2). We have not found associations between serum levels of survivin with creatinine levels (rho=0.02; p=0.81) or with bilirubin levels (rho=0.08; p=0.34).

DiscussionThe association between septic patient mortality and low blood survivin concentrations controlling for sepsis severity found in multiple logistic regression is the main new finding of our study.

Survivin inhibit the activation of caspase-9 and therefore the intrinsic apoptosis pathway.5 We think that this association that we found between high serum survivin concentrations and lower mortality could mean that those patients who will survive to sepsis have a higher inhibition of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway. A promising fact is that the use of simvastatin in animal models of sepsis have increased survivin activity and reduced apoptosis in cardiomyocytes12 and in renal tubular cells.13 However, there were no found differences in mortality rate according to receive simvastatin previously to sepsis diagnosis or not, and any patients received simvastatin during ICU stay.

The mortality rate in our series (36.8% in the first 30 days) might seem high compared with the rate of a study with 2980 patients from 72 Spanish ICU (ICU mortality of 24%).14 However, in that study the mean SOFA was 8.6 and in our study was 10.1. In addition, the rate of patients in whom the microorganism was not isolated was high in our study, and we don’t have a clear explanation for it.

The non-determination of blood survivin concentrations in healthy subjects and during the follow-up of patients are two limitations of our study. Another limitations were the non-determination of apoptosis degree in tissues and of other blood apoptosis biomarkers. Other limitations were that we did not registered the number of loss patients (due to exclusion criteria or not wanting to participate), the exact moment when blood samples were taken (although were taken during the first 4h of sepsis diagnosis) and the time to control of infection focus. In some cases the sample was taken before the patient was admitted to the ICU, although this fact was neither registered. But the informed consent was obtained in all cases before inclusion. Another limitation was that we have not registered the body mass index and this molecule is produced in large quantities by adipose tissue stem cells and obese people have been shown to have higher blood levels.15 Other limitations were the low AUC of blood survivin concentrations to predict sepsis mortality and the lower prediction capability in respect to other severity scores (APACHE-II or SOFA). However, the objective of our study was not to determine whether serum survivin concentrations could replace severity scores to estimate sepsis prognosis; but, to determine whether exist an association between serum survivin concentrations and mortality of septic patients. We think that the association between septic patient mortality and low blood survivin concentrations found in our study and the possibility to modulate survivin activity according to results of animal studies could motivate the interest to research about survivin in septic patients and to study the effect of agents that increase survivin activity in those patients.

ConclusionsThere is an association between septic patient mortality and low blood survivin concentrations.

Key messages- -

Survivor septic patients showed higher survivin levels than non-survivor.

- -

There is association between low blood survivin levels and mortality of septic patients.

- -

LLo conceived, designed and coordinated the study, participated in acquisition and interpretation of data, and drafted the manuscript.

- -

MMM and RO participated in acquisition of data.

- -

APC, CFM and AFGC carried out the determinations of serum caspase-8 concentrations.

- -

AJ participated in the interpretation of data.

All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and made the final approval of the version to be published.

FundingThis study was supported by a grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI-18-00500) (Madrid, Spain) and co-financed with Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.