In view of the exceptional public health situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, a consensus work has been promoted from the ethics group of the Spanish Society of Intensive, Critical Medicine and Coronary Units (SEMICYUC), with the objective of finding some answers from ethics to the crossroads between the increase of people with intensive care needs and the effective availability of means.

In a very short period, the medical practice framework has been changed to a ‘catastrophe medicine’ scenario, with the consequent change in the decision-making parameters. In this context, the allocation of resources or the prioritization of treatment become crucial elements, and it is important to have an ethical reference framework to be able to make the necessary clinical decisions. For this, a process of narrative review of the evidence has been carried out, followed by unsystematic consensus of experts, which has resulted in both the publication of a position paper and recommendations from SEMICYUC itself, and the consensus between 18 scientific societies and 5 institutes/chairs of bioethics and palliative care of a framework document of reference for general ethical recommendations in this context of crisis.

Ante la situación excepcional de salud pública provocada por la pandemia por COVID-19, desde el grupo de ética de la Sociedad Española de Medicina Intensiva, Crítica y Unidades Coronarias (SEMICYUC) se ha promovido un trabajo de consenso con el objetivo de encontrar algunas respuestas desde la ética a la encrucijada entre el incremento de personas con necesidades de atención intensiva y la disponibilidad efectiva de medios.

En un periodo muy corto de tiempo, se ha cambiado el marco de ejercicio de la medicina hacia un escenario de «medicina de catástrofe», con el consecuente cambio en los parámetros de toma de decisiones. En este contexto la asignación de recursos o la priorización de tratamiento pasan a ser elementos cruciales, y es importante contar con un marco de referencia ético para poder tomar las decisiones clínicas necesarias. Para ello, se ha realizado un proceso de revisión narrativa de la evidencia, seguida de uconsenso de expertos no sistematizado, que ha tenido como resultado tanto la publicación de un documento de posicionamiento y recomendaciones de la propia SEMICYUC, como el consenso entre 18 sociedades científicas y 5 institutos/cátedras de bioética y cuidados paliativos de un documento marco de referencia de recomendaciones éticas generales en este contexto de crisis.

The current pandemic due to the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus that causes the COVID-19 disease is an unprecedented challenge for the entire healthcare system—especially for intensive care units (ICU)—because the most severe cases can develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), sepsis/septic shock, and multi-organ failure including acute kidney injury and cardiac damage.1

While most people with COVID-19 develop mild or uncomplicated disease, the early data from China show that 14% develop serious disease that requires hospitalization and 5% need to be hospitalized in an intensive care units (ICU).2 In Lombardy, Italy the total ICU capacity prior to the crisis was 720 beds (2.9% of the overall number of hospital beds in a total of 74 hospitals, with an occupation rate between 85% and 90% during the months of Winter). Two weeks into the outbreak the system collapsed. The patients admitted to the ICUs due to COVID-19 disease were already 556 (equivalent to the 12% of all cases that tested positive and 16% of all hospitalized patients).3

The experience gained in other countries and the reality lived daily in some of our hospitals shows the huge imbalance between the number of patients who require invasive mechanical ventilation and the actual resources available. According to data recently published by the Spanish Society of Intensive, Critical and Coronary Unit Medical Care (SEMICYUC),4 the number of ICU beds in Spain is around 3600, which is a 7.7 bed ratio for every 100 000 inhabitants (compared to 29.2/100 000 inhabitants in Germany and 4.2/100 000 inhabitants in Portugal jut to mention 2 examples of neighboring countries).5 To this day (March 22th, 2020), the number of patients (cumulative incidence) with COVID-19 who required ICU admission in Spain is already 1785.6

The dilemma between this anticipated excessive need for invasive ventilation and the limited resources available will probably be leading us to a situation of “disaster medicine” where difficult moral decisions will need to be made for allocating resources and prioritizing patients. In the short and long-term, this reality will have a tremendous impact on the patients and their families. Also, health workers will be impacted, which may be even more catastrophic that the disease per se.7

Since difficult ethical decisions will need to be made based on solid criteria and basic moral principles grounded on the equal and fair provision of services, the SEMICYUC ethics committee has promoted consensus in order to hekp healthcare workers handle this complex situation.

MethodologyGiven the urgency of the current situation, an agile and resolute 3-stage methodology has been designed:

- 1

Rapid summary of the medical literature published on the ethics behind decision-making processes under exceptional circumstances of pandemic related crises.

- 2

Design of an online, non-systematic consensus document between health workers from SEMICYUC ethics committee and experts on bioethics, geriatrics, and palliative care.

- 3

Consensus document including general recommendations signed by scientific societies and institutional ethics committees.

After extensive search of the medical literature available, 9 especially relevant papers have been found on the ethics behind decision-making processes under exceptional situations in pandemic related crises.7–15 Three of them are articles that specifically reviewed aspects of palliative care in this context.16–18

Designing the documentBased on the actual scientific evidence available and the online work conducted by the authors of this article, the first document draft was envisioned: “Moral recommendations for decision-making processes in the exceptional situation of crisis due to the current COVID-19 pandemic in the intensive care unit setting”. Two are the objectives of this manuscript: 1) bring support to the healthcare workers in the difficult decisions they will have to make by providing them with generally agreed criteria allowing them to share responsibility in the difficult decisions made under situations that require a great emotional load, and 2) specify criteria of adequacy and resource allocation in situations of exceptionality and scarcity.

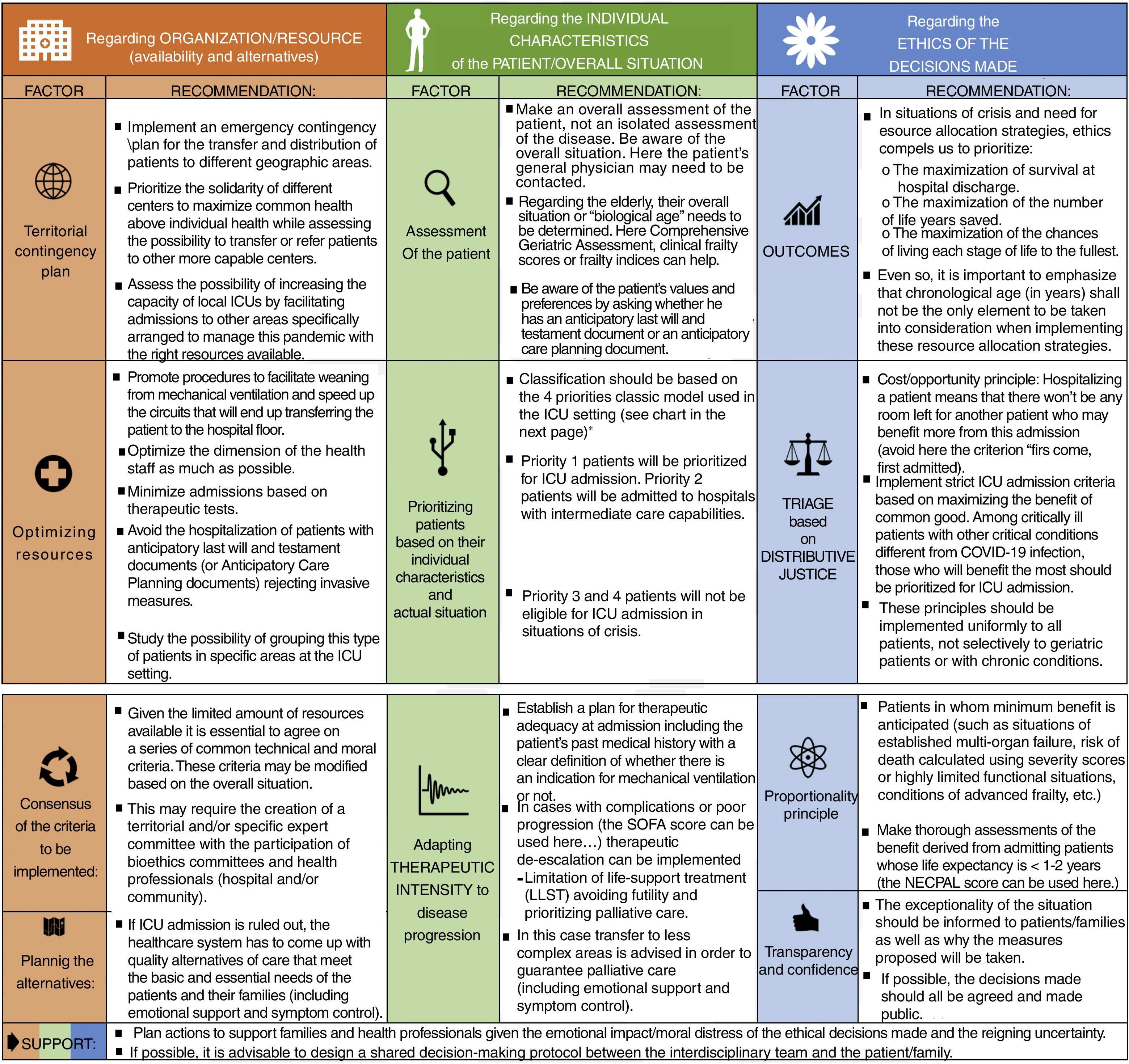

General recommendationsFirst, a series of general recommendations were developed that can be grouped into 3 large categories:

- A

Recommendations regarding organization, availability of resources and alternatives: 1) need to implement a territorial contingency plan with solidarity among different centers as the leading criterion; 2) optimization of personal, structural, and material resources; 3) consensus of common technical and ethical criteria by proposing the creation of committees including territorial experts, and 4) planning alternatives, especially for people who may need palliative care treatment.

- B

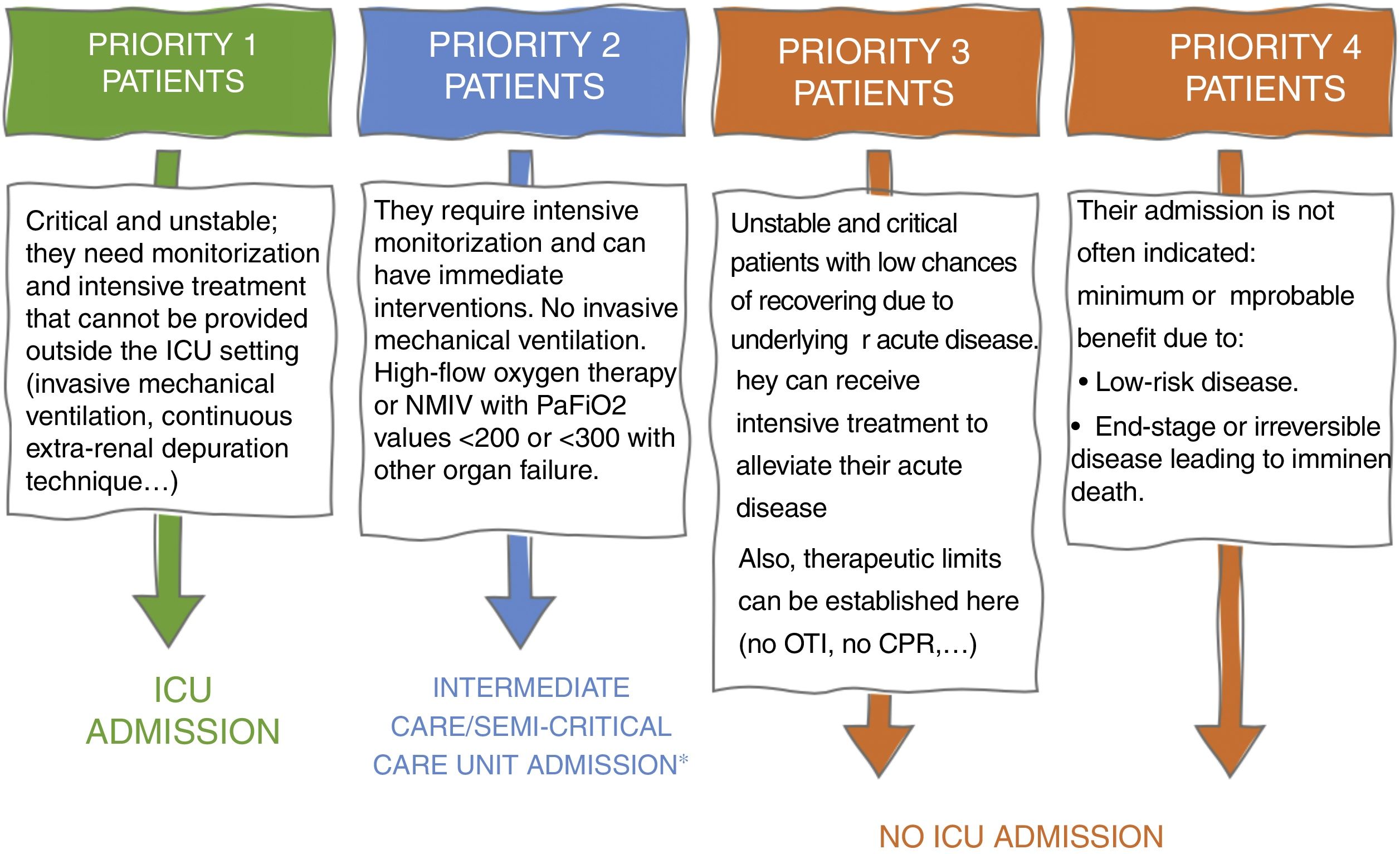

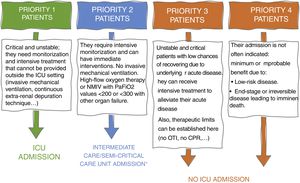

Recommendations regarding the patient’s individual characteristics and overall situation. Need to perform a comprehensive assessment 1) including a multidimensional assessment of the overall situation or “biological age” of the patient with his values and preferences including the possibility that he has signed an Anticipatory Last Will and Testament Document (ALWTD) or an Anticipatory Care Planning (ACP); 2) with better arrangements for ICU admissions based on a model of 4 categories of prioritizing these admissions (Fig. 1), and 3) taking into consideration the need for a dynamic adequacy of care by guaranteeing quality palliative care in cases with poor progression.

Figure 1.Model of 4 categories for prioritizing and allocating patients based on their individual characteristics and current situation.

CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; OTI, orotracheal intubation.

*Consider the option of admitting priority 2 patients in other health areas such as intermediate care units when available and not saturated with priority patients.

- C

Recommendations regarding moral decisions: 1) need to apply specific moral criteria for situations of crisis by implementing an allocation strategy to maximize survival after hospital discharge and the number of life years saved with this thought in mind: chronological age (in years) should not be the only element to take into account during the implementation of allocation strategies; 2) triage should be based on principles of distributive justice—prioritizing the best “cost/opportunity” ratio—and proportionality—by not hospitalizing patients with minimum benefits foreseen (like patients with advanced disease related limited life expectancy)—; and 3) if possible, recommendation to implement a shared decision-making process between the health team and the patient/family through respectful and transparent communication in a context of confidence.

Beyond these 3 categories, the medical literature is very consistent on the need to plan actions to support families and healthcare workers given the emotional impact/moral distress that follows the moral decisions made and the uncertainty surrounding the entire process.

Specific recommendations- A

In an attempt to provide medical care to all patients with acute respiratory failure (ARF), it is advisable to prioritize the fair allocation of admission based on objective criteria of adequacy and expectations of resolution of the process with good quality of life and functionality. Based on this perspective, and in a situation of crisis and lack of resources, it is advisable that only priority 1 and 2 patients (Fig. 1) should be eligible for ICU and/or intermediate/semi-critical care unit admission.

- B

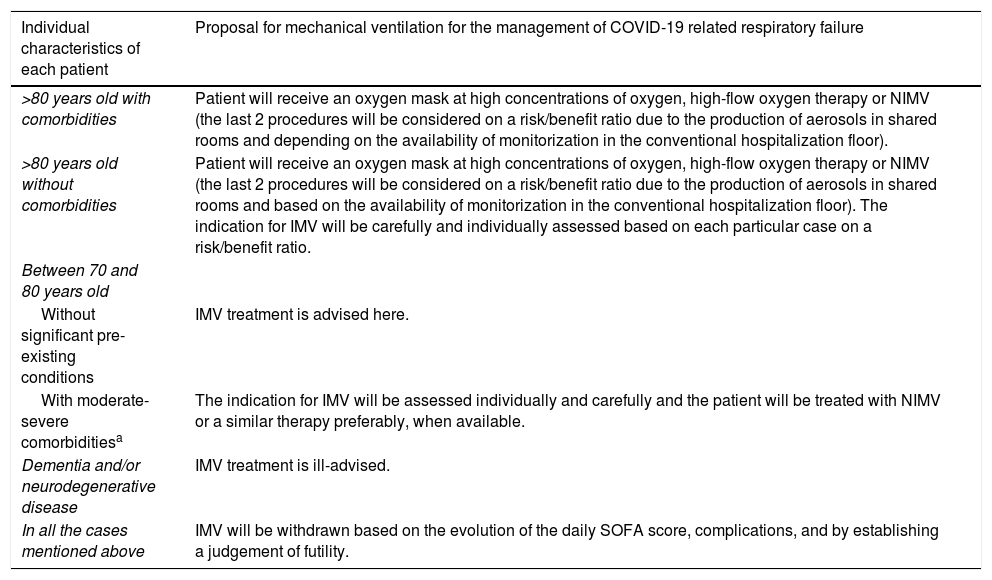

It is advisable to adequate the ventilation of patients with ARF to the individual characteristics of each patient (Table 1). Comorbidity here will be defined as the presence of several disease process different from the current one whose severity can be measured using the Charlson Comorbidity Index: no comorbidity (0–1); high comorbidity (>3).

Table 1.Indications for IMV y NIMV based on the individual characteristics of each patient.

Individual characteristics of each patient Proposal for mechanical ventilation for the management of COVID-19 related respiratory failure >80 years old with comorbidities Patient will receive an oxygen mask at high concentrations of oxygen, high-flow oxygen therapy or NIMV (the last 2 procedures will be considered on a risk/benefit ratio due to the production of aerosols in shared rooms and depending on the availability of monitorization in the conventional hospitalization floor). >80 years old without comorbidities Patient will receive an oxygen mask at high concentrations of oxygen, high-flow oxygen therapy or NIMV (the last 2 procedures will be considered on a risk/benefit ratio due to the production of aerosols in shared rooms and based on the availability of monitorization in the conventional hospitalization floor). The indication for IMV will be carefully and individually assessed based on each particular case on a risk/benefit ratio. Between 70 and 80 years old Without significant pre-existing conditions IMV treatment is advised here. With moderate-severe comorbiditiesa The indication for IMV will be assessed individually and carefully and the patient will be treated with NIMV or a similar therapy preferably, when available. Dementia and/or neurodegenerative disease IMV treatment is ill-advised. In all the cases mentioned above IMV will be withdrawn based on the evolution of the daily SOFA score, complications, and by establishing a judgement of futility. IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; NIMV: non-invasive mechanical ventilation.

Charlson Comorbidity Index >3.

From the general recommendations established by SEMICYUC ethics committee, a consensus paper was designed as a draft document whose final iteration was the consensus manuscript: “General recommendations for the management of difficult moral decisions and adequacy between healthcare intensity/allocation to intensive care units in exceptional situations of crisis” shown on Fig. 2.

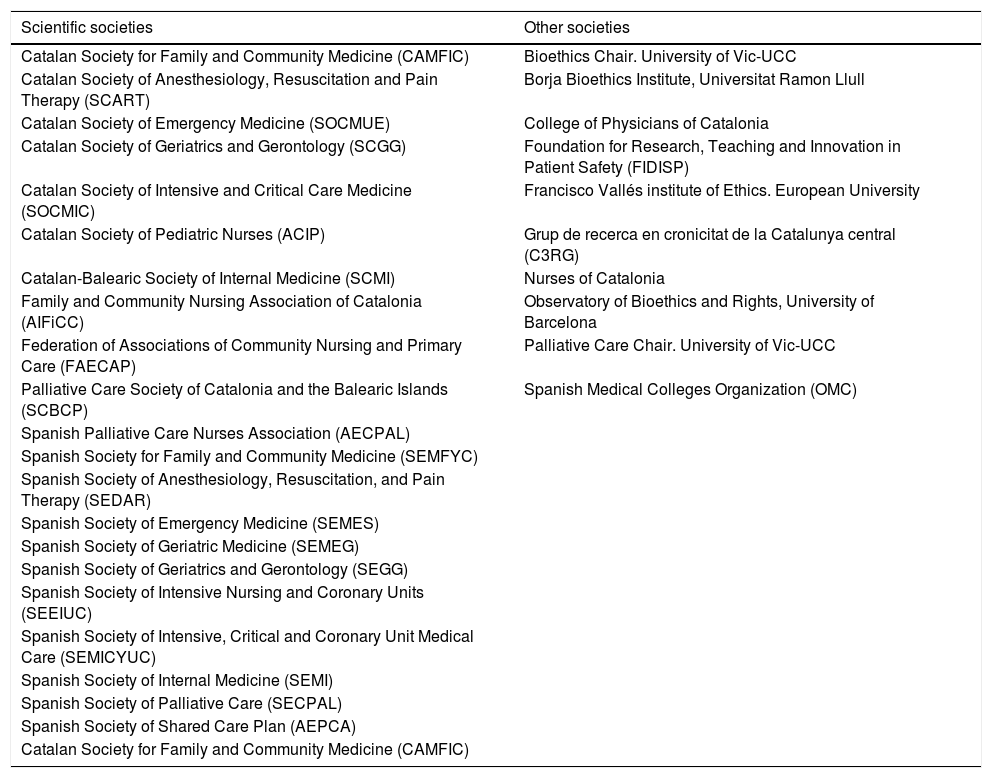

Twenty-one scientific societies, 6 ethics committees on bioethics/palliative care plus another 5 entities participated in the writing of this final consensus document (Table 2).

Societies participating in the consensus document (in alphabetical order).

| Scientific societies | Other societies |

|---|---|

| Catalan Society for Family and Community Medicine (CAMFIC) | Bioethics Chair. University of Vic-UCC |

| Catalan Society of Anesthesiology, Resuscitation and Pain Therapy (SCART) | Borja Bioethics Institute, Universitat Ramon Llull |

| Catalan Society of Emergency Medicine (SOCMUE) | College of Physicians of Catalonia |

| Catalan Society of Geriatrics and Gerontology (SCGG) | Foundation for Research, Teaching and Innovation in Patient Safety (FIDISP) |

| Catalan Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine (SOCMIC) | Francisco Vallés institute of Ethics. European University |

| Catalan Society of Pediatric Nurses (ACIP) | Grup de recerca en cronicitat de la Catalunya central (C3RG) |

| Catalan-Balearic Society of Internal Medicine (SCMI) | Nurses of Catalonia |

| Family and Community Nursing Association of Catalonia (AIFiCC) | Observatory of Bioethics and Rights, University of Barcelona |

| Federation of Associations of Community Nursing and Primary Care (FAECAP) | Palliative Care Chair. University of Vic-UCC |

| Palliative Care Society of Catalonia and the Balearic Islands (SCBCP) | Spanish Medical Colleges Organization (OMC) |

| Spanish Palliative Care Nurses Association (AECPAL) | |

| Spanish Society for Family and Community Medicine (SEMFYC) | |

| Spanish Society of Anesthesiology, Resuscitation, and Pain Therapy (SEDAR) | |

| Spanish Society of Emergency Medicine (SEMES) | |

| Spanish Society of Geriatric Medicine (SEMEG) | |

| Spanish Society of Geriatrics and Gerontology (SEGG) | |

| Spanish Society of Intensive Nursing and Coronary Units (SEEIUC) | |

| Spanish Society of Intensive, Critical and Coronary Unit Medical Care (SEMICYUC) | |

| Spanish Society of Internal Medicine (SEMI) | |

| Spanish Society of Palliative Care (SECPAL) | |

| Spanish Society of Shared Care Plan (AEPCA) | |

| Catalan Society for Family and Community Medicine (CAMFIC) |

As far as the authors know, this is the first consensus document—an extraordinarily wide one by the way—ever published in the scientific medical literature on moral and ethical recommendations to make difficult decisions in pandemic related situations of crisis at the ICU setting. Although there may be some limitations associated with how fast it was designed and developed, the 3-step methodology used gave rise to an organized and rigorous proposal.

In the first place, we saw a lack of specific papers published in the medical literature on ethics and moral under situations of epidemiological crises. Yet despite this fact, we should mention that most studies found emphasize the need to provide the resource allocation process with ethical premises. They also emphasize the need to offer quality alternatives to alleviate symptoms in cases with poor disease progression.16

On the other hand, it is striking to see the need of having to apply the principle of justice to every patient uniformly, and not just selectively based on their geriatric profile or chronic health problems.8 Therefore, although there is consensus that we should try to maximize the number of people that will be benefited, the disability-free survival at hospital discharge, and the number of life years saved, most papers separate the resource allocation decision from the patient’s chronological age as the only valid strategy, thus opening the door to assess other variables like the degree of frailty, which is equivalent to the patients’ “biological age”.19,20

Finally, beyond developing step-wise proactive strategies based on epidemiological assessments, clinical knowledge, and resource optimization, the process of handling a crisis of public health requires reflecting on values such as responsibility, inclusion criteria, transparency, sensitivity or rationality.7 The moral frameworks such as the consensus document described above will guide the healthcare workers and authorities in the difficult decision-making process that can eventually minimize collateral damage.12

Conflicts of interestNone reported.

Please cite this article as: Rubio O, Estella A, Cabre L, Saralegui-Reta I, Martin MC, Zapata L, et al. Recomendaciones éticas para la toma de decisiones difíciles en las unidades de cuidados intensivos ante la situación excepcional de crisis por la pandemia por COVID-19: revisión rápida y consenso de expertos. Med Intensiva. 2020;44:439–445.