Edited by: Federico Gordo - Medicina Intensiva del Hospital Universitario del Henares (Coslada-Madrid)

Last update: December 2023

More infoSARS-CoV2 pandemic has led to multiple changes in healthcare. Unexpected changes in the incidence and etiology of infectious pathologies have been described. Among them, an increase of Streptococcus pyogenes infection prevalence has been described in 2022.1–3S. pyogenes community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) outbreaks were described in the early 20th century as a complication of viral infections such as influenza and measles.4 Case reports and small case series have been published ever after.5,6 In 2017 influenza season, S. pyogenes CAP outbreak was described in Australia, in which 92% of patients required ICU admission and 84.6% died due to the infection.7 We have reviewed all S. pyogenes CAP treated in our ICU in the last eight years. Hospital Ethics Committee reviewed and approved the study (code 2023-254-1).

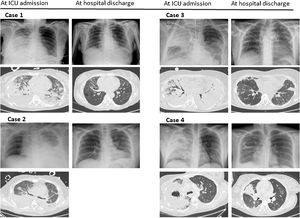

Case 1 (March-2016). A 50 years-old woman with medical background of high blood pressure presented to the emergency room with a four-days clinical picture of sore throat, high fever, productive cough, right chest pain, and dyspnoea. Complementary test results are depicted in Table 1 and Fig. 1. She was admitted to ICU due to septic shock and respiratory failure. Mechanical ventilation (MV) was initiated. The patient received ceftriaxone and levofloxacin. S. pyogenes was detected in blood cultures and sputum and linezolid substituted levofloxacin. Besides, nasopharyngeal swab was positive to H1N1 influenza. Clinical course was complicated by pleural empyema, pneumothorax and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). Tracheostomy was performed after 21 days of MV. Finally she was disconnected from MV after 63 days, and she was transferred to general ward after 72 days in ICU. She needed another 21 days in the ward to recover motor independence.

Biochemical and haematological analysis at ICU admission.

| Age | SAPSIII | SOFA | Sex | Bilateral pneumonia | Multilobar pneumonia | Leucocytes (cell/mm3) | Lymphocites (cell /mm3) | PCT (ng/mL) | CRP (mg/l) | Platelets (cell/mm3) | Fibrinogen (mg/dl) | PaO2/FiO2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 50 | 47 | 12 | Female | Yes | Yes | 610 | 130 | 18.06 | 202 | 136,000 | 628 | 83 |

| Case 2 | 40 | 59 | 12 | Male | No | Yes | 2580 | 90 | 142 | 385.5 | 125,000 | 810 | 64.5 |

| Case 3 | 51 | 80 | 16 | Female | Yes | Yes | 15,630 | 790 | 77.56 | 516.6 | 90,000 | 940 | 77 |

| Case 4 | 32 | 39 | 8 | Female | No | Yes | 10,450 | 100 | 8.22 | 364 | 139,000 | 956 | 194 |

ICU: Intensive Care Unit; PCT: procalcitonin; CRP C-reactive protein.

Case 2 (February-2018). A 40 years-old man without medical background presented to the emergency room with a one-week clinical picture of productive cough, high fever and left chest pain. Complementary test results are depicted in Table 1 and Fig. 1. He was admitted to ICU due to respiratory failure, septic shock and acute renal failure. Empirical antibiotic treatment was ceftriaxone plus azithromycin. Left pleural empyema was drained at ICU admission and S. pyogenes was isolated in pleural fluid. Azithromycin was therefore changed to linezolid. Respiratory virus PCR panel was positive to Metapneumovirus. MV and prone position ventilation was needed due to severe ARDS. Clinical course was complicated by Pseudomonas aeruginosa VAP. Tracheostomy was performed after 19 days of MV and could be withdrawn after 16 days. He was transferred to general ward after 36 days in ICU and to his home ten days later.

Case 3 (July-2022). A 51 years-old woman without medical background, and with a complete SARS-CoV2 vaccination schedule presented to a regional hospital with a clinical picture of fever, productive cough and dyspnoea following a COVID19 diagnosis. Complementary test results are depicted in Table 1 and Fig. 1. She was admitted to ICU due to respiratory failure, septic shock, acute renal failure and intravascular disseminated coagulopathy. She was empirically treated with piperacillin-tazobactam plus linezolid. Severe hypoxia was refractory to MV, prone position ventilation and alveolar recruitment manoeuvres, and therefore she was proposed for ECMO treatment two days later. The patient was connected to VV-ECMO and transferred to our ICU. S. pyogenes ADN was detected in alveolar fluid and treatment was shifted to ceftaroline and tedizolid. After 14 days, VV-ECMO was withdrawal and the patient was successfully extubated ten days later. However, a P. aeruginosa nosocomial pneumonia developed and dragged the patient into a new situation of sepsis and respiratory failure. The patient was newly intubated. Once again, given the refractoriness to other therapeutic measures, it was decided to switch back to ECMO. The clinical course was very intricate and included the need for amputation of the right hand due to ischemia. After 40 days tracheal cannula and MV were withdrawal and 9 days later the second VV-ECMO treatment could be finished. She was discharged from ICU after 92 days and discharged home eleven days later.

Case 4 (December-2022). A 32 years-old woman with medical background of type 1 diabetes mellitus presented to the emergency room with a four days clinical picture of sore throat, productive cough, fever and right forearm pain. Complementary test results are depicted in Table 1 and Fig. 1. She was admitted to ICU due to respiratory failure, and clinical suspect of necrotizing fasciitis. Empirical treatment comprised meropenem plus levofloxacin. Respiratory support consisted in high flow nasal oxygen cannula. Debridement was performed the following day and S. pyogenes was detected by PCR in muscle tissue sample. Respiratory samples were not available, and we assumed that the etiology of the pneumonia was the same. Antibiotic treatment was switched to ceftaroline plus linezolid. Local surgery was needed in three more points till surgical edges could be closed. The patient was discharged from ICU after 10 days and discharged home 19 days later.

Our results are consistent with recently published findings on the notable increase in S. pyogenes infections. We have detected two cases of CAP due to S. pyogenes in 2022, which represents a notable increase compared to the previous seven years (from 0.38% of all bacterial CAP to 3.2% in 2022). Nowadays the only attributable risk factor for this global S. pyogenes resurgence is SARS-CoV2 pandemia.1–3 Our serious clinical cases are the ultimate expression of S. pyogenes pneumonia. All of them had a complex course, a prolonged ICU stay and a high incidence of superinfections. In fact, the third case is our first experience in the use of two consecutive therapies with VV-ECMO. Our cases were treated with a beta-lactam and a toxin-producing inhibitor. 2022 cases were treated with ceftaroline. This clinical decision was based on the good results obtained by ceftaroline compared to ceftriaxone in S pneumoniae CAP,8 but it was also due to the pharmacokinetic doubts that have arisen regarding ceftriaxone in critically ill patients and the lower MIC values exhibited to ceftaroline compared to ceftriaxone by S. pyogenes.9,10 Our four patients were able to overcome S. pyogenes pneumonia and illustrate the need to consider this etiology in order to carry out correct therapeutic management and a proactive search for local and systemic complications.