Value-Based Health Care (VBH) is a concept introduced by Michael E. Porter in 2006. It means value is a concept that guides health care practice towards activities that generate the best possible health outcomes, and that are relevant to patients.1

But… Who defines value? In the NEJM, it is defined as the value defined by the patient, not by the service provider.1 And why is it important?

The patient has become an active agent in their health, making informed shared decisions and taking an increasingly prominent role in their health. We have moved from a paternalistic paradigm in which the clinician decides based on scientific knowledge, to a paradigm in which patients decide by themselves, with information and help from professional training, what is most beneficial for their health in their specific and particular situation within a framework of shared decision-making.2 In this new paradigm, considering the patient’s experience is very relevant and can be very revealing for clinicians.

The Beryl Institute defines patient experience as “the sum of all interactions, shaped by an organization culture, that influence patient perceptions across the continuum of care”.3 The continuum of care refers to the entire integrated care process of an illness.

The fragmentation of care processes, specialization, coordination, and transfers among professional services can bring associated hidden difficulties or “pain points” that worsen outcomes and value from the patient’s perspective. Analyzing and understanding these hidden needs can transform and innovate our routine daily practice through co-creation to achieve health outcomes that matter to patients and are more efficient for the system.

The ICU experience impacts patients and families. It is associated with physical, mental, and cognitive sequelae that can persist even after ICU discharge (known as the post-ICU syndrome), making it necessary to implement prevention and support strategies to mitigate these negative outcomes.4

Former experiences regarding patient experience at the ICU setting have identified unmet needs such as pain control, discomfort, communication difficulties, insomnia, and post-ICU syndrome.5 These experiences are valued negatively by patients and can be potentially preventable and avoidable.

Improving patient experience is thus the result of a collaborative and multidisciplinary discovery process to identify unmet needs of patients related to their care process and illness. These needs may include information, time management, accessibility, the impact of illness on activities of daily life, emotional needs, etc.6

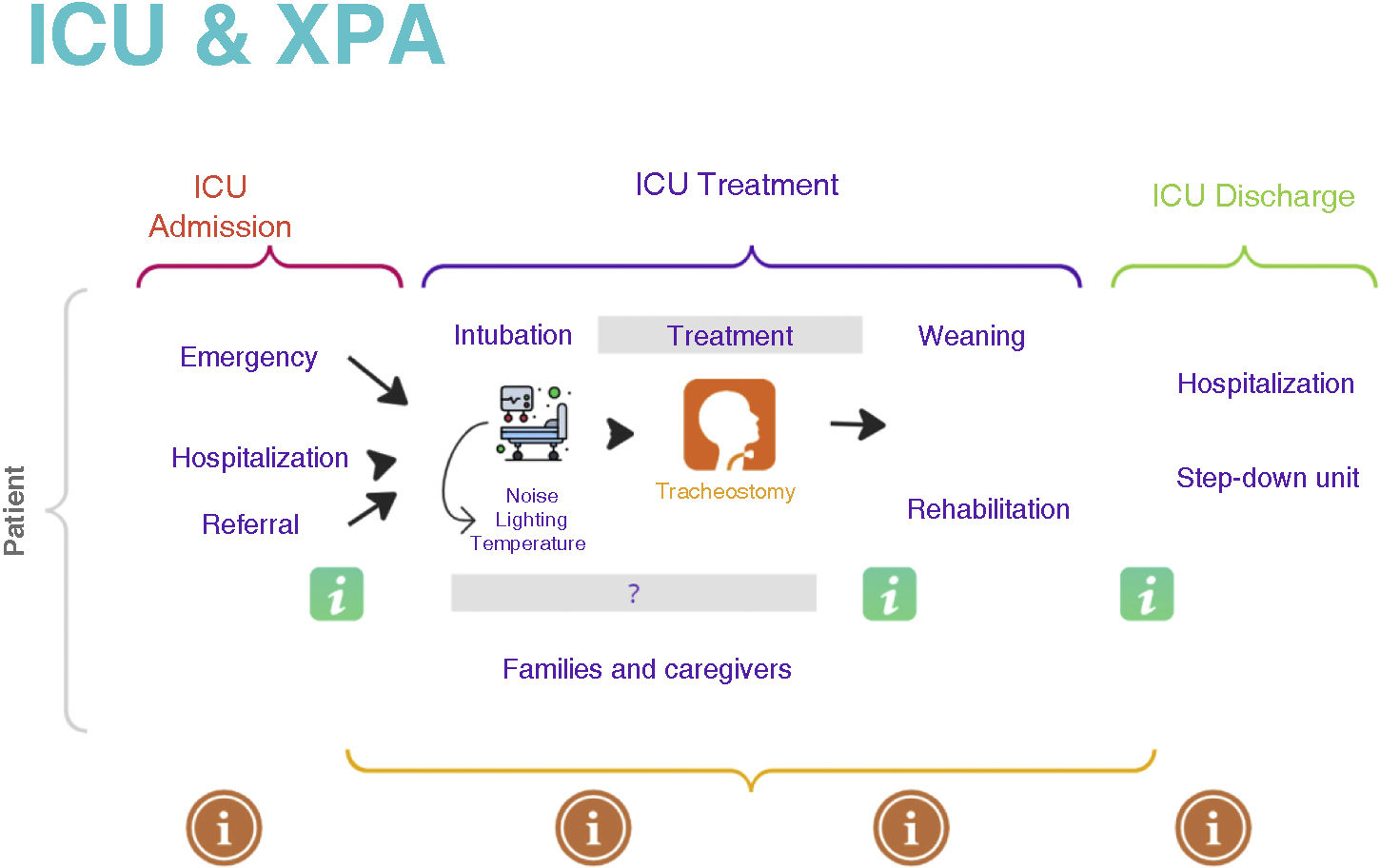

The first step would be to understand this need and construct the “Journey Map” of the ICU process (see Fig. 1) with professionals, to define the people involved in the processes, group patients into archetypes or groups based on specific needs seeking the greatest patient representativeness, and finally explore patient experience in the different groups through qualitative/quantitative methodologies such as focus groups, interviews, and/or surveys. The team should be transdisciplinary to provide different perspectives of the process, with clinical leadership that offers a vision from knowledge, ensures the implementation of improvements, and can provide feedback on results through indicators (PREMS and PROMS).

Concrete actions at the ICU setting such as improving empathy, communication, and information for patients and families at different times and in different formats, addressing emotional needs, managing discomfort triggers, structuring patient transitions from ICU to ward, adapting structures, and even improving the experience of professionals have a clear impact on the patient experience at the ICU setting.5,7,8 Moreover, all these actions can impact results that can be evaluated with indicators like PREMS, which are starting to be quality indicators in ICUs.5

It is obvious that it is necessary, and although it is also fashionable… it is here to stay. There are different experiences in hospitals that are integrating patient experience into their routine clinical practice, gradually transforming organizations and organizational cultures. Although there are various actions in this regard, what is common is the need for commitment from leadership, management, health care administrations, and the promotion of strategy from clinical leadership.

Table 1 shows factors recently described in an article on suggestions for improving the experience of critically ill patients.7

Patient experience and improvement suggestions.

| 1. Explore aspects of patient experience in the broadest terms.2. Consider patient factors, environmental factors, care, and intervention.3. Assess patient opinions through their representatives.4. Evaluate patient experience early in the post-ICU phase to better recall ICU experiences after excluding delirium.5. Assess patient experience later to detect adverse sequelae (anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder).6. Link aspects of patient experience with the quality of care at the ICU setting. |

Positive intensive care would attend to physiological needs but also psychological needs and well-being even after ICU discharge.5 Simple actions such as incorporating diaries in the ICU (information for patients) not only improve patient outcomes but also their quality of life by filling memory gaps that occur after a prolonged ICU stay, for example.9 The issue of coordinating several professionals in one visit to optimize patient time management, or nursing interventions to empower patients at ICU discharge.10

In conclusion, incorporating patient experience is a way to add value and meaning to our routine daily practice, implementing a lever for change to transform the healthcare system, redesigning processes, incorporating the patient’s voice to gain value, creating an organizational culture that generates value—value that translates into results that matter to people, contributing to quality, safety, system efficiency, and sustainability. A correct understanding of patient experience can help improve the ICU experience and outcomes for patients and professionals.

It’s not just a trend, but a necessity.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.