In our country, access to university teaching falls under the Royal Decree-Act 1.312/2007 modified by the Royal Decree-Act 415/2015 and the new evaluation criteria established by the National Agency for Quality Assessment and Accreditation (ANECA) that became effective back in November 20171 (Table 1, see supplementary data).

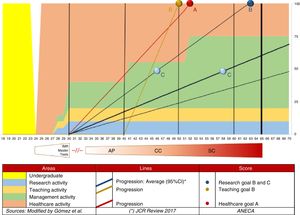

This letter analyzes the initial mandatory requirements established by ANECA to access the staff of university professors while taking into consideration the professional dedication by intensivists2 (Fig. 1).

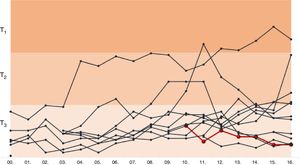

If we take a look at where Spanish journals rank within the Journal Citation Reports (JCR) we will see that most national journals of medical-clinical specialties are to be found on the JCR T3 (tercile) (Fig. 2). On the other hand, in the Scimago Journals & Country Ranking (SJR), an alternative resource to JCR designed by a CSIC Task Force and several Spanish universities, since 2005, the medical journal Medicina Intensiva is on the Q2 (quartile) and it is the best positioned of all, D1 (1996–2017) (decile), compared to the other medical-clinical specialties. Therefore, the first conclusion we can draw here is that publishing on national medical journals, in general, and on Medicina Intensiva in particular does not count according to the ANECA criteria.

A simple search on the JCR using Boolean operators shows that, of all the journals that fell into the T1+T2 of the Critical Care Medicine category during 2017, 14,832 papers were published, of which only 97 (0.61%) were signed by a Spanish author identified as an intensivist. But, if we exclude those that do not meet the ANECA criteria, only 48 papers would count. Also, if we only count leading authors, only 23 papers would remain. And if we analyze the abstracts from these 23 papers, we would see that the average time of the studies was 2.3 years (confidence interval [CI] 95%: 1.3–3.3). This shows a rhythm publication of 0.43 papers/year (95% CI: 0.77–0.30). Also, in most cases, the author is from Madrid and/or Barcelona.

This means that (Fig. 1) ANECA research level A is actually out of reach (at an average rhythm of publication, it would take us 123 years). Level B would be achieved at 63–64 years old for those who publish at a rhythm beyond 95% CI. Level C would be achieved at 58–59 years old for those who publish at an average rhythm, and at 46–47 years old for those who publish at a rhythm beyond 95% CI. It seems that only 2.5% of all intensivists would meet these criteria at a reasonable age, and also that if this were to happen, it would probably happen in Madrid or Barcelona. And all this if starting publishing as the lead author at 30 years old and dedicating only 10% of the professional careers to research – a percentage that does not change depending on the professional category.

TeachingOn this issue, two aspects seem weird to us: first that to become accredited as a university professor, the teaching achievements are precisely the least demanding of all and, second that an alleged level A accreditation in teaching does not facilitate the accreditation in other areas.

When it comes to our own specialty, the most reasonable option would be part-time dedication as an assistant professor for 10 years. Thus, by being an associate professor at 40 years old, we would be eligible for an ANECA level B teaching accreditation at 50 (Fig. 1). However, becoming an assistant professor at 40 does not seem like an easy accomplishment either given the actual professional instability (contracts on an on-call basis, task overload, extra shifts, etc.) that goes on for about a year after finishing the residency. We should take into consideration here the teaching time devoted by an intensivist – considered 10% of the professional activity – that does not change based on the professional category.

Transfer and professional activityIt seems reasonable to us that the most adequate way to do this would be to accredit four (4) achievements of professional experience. Thus, for intensivists whose healthcare activity amounts to over 50% of their professional activity (Fig. 1) this should not be a problem.

The most significant data when it comes to criteria of professional experience is that one single achievement equals eight (8) years of professional experience as an intensivist and that it can be doubled to a maximum of 2 achievements=20 years. Based on this score, the other two (2) achievements left could be accredited with a 2-year contract as a specialist at a foreign center and just by being president of a hospital commission for about four (4) years. This is the same as to say that 10 years of professional experience (daily workload, 5–6calls/month, etc.) score the same as 2 years at a foreign center or 4 years as president of a clinical commission.

Other achievements: management and academic trainingIn the best-case scenario of accreditation, the achievements in management would not be scored for this last level of accreditation. It is ironic that professional activity – that grows bigger with one's professional career (Fig. 1) – does not score for the ANECA criteria. Thus, only the level B accreditation in academic training based on the three relevant achievements remains: competitive grants or pre- or post-doctoral contracts, special awards, thesis quality traits, and other.

Comments and conclusionsThe goals of the actual system of accreditation were to avoid college professors who studied in the same university they would be teaching at and improve the quality of teaching. Reality is somehow different: medical students are not prepared for a real professional activity, there is a gradual decrease in the number of accredited professors, and, ultimately, subjects are not being taught or are taught thanks to the assistant professors’ personal comittment.3

We believe that medical schools should include departments highly specialized in research and other departments specialized in teaching and healthcare training, that is, two very different routes to become accredited. The ANECA criteria overestimate research, do not contemplate these options, and deny the possibility of choosing what kind of college professors universities wish to hire.

This is something that the executive college staff has already said: “in medicine, I want pediatricians who can see kids, not experts in mouse skin transplants”4; “[…] the number of permanent professors of medical schools has been dropping progressively […] while becoming cause for concern for both the teaching and research personnel. The way they see it, their expectations of professional development at university teaching staff are growing thinner”.5

These are the conclusions we draw after analyzing the ANECA criteria:

When it comes to research: they don’t seem to know what the actual situation of Spanish clinical research really is and they have elevated the amount of achievements required for accreditation to a ridiculous number.

When it comes to teaching: they do not take into consideration the actual teaching skills and talent of university professors, their actual dedication or teaching in other settings aside from the university context.

When it comes to transfer and healthcare activity: the achievements of transfer from an intensivist's point of view seem absurd to us and the achievements of healthcare activity get to the point of smearing how hard it is to provide healthcare in general and, in particular, is certain specialties such as intensive medicine while being extremely demanding when it comes to the level of continuous healthcare provision required.

In sum, here's our message to all those with a clear calling for teaching: intensivists, lose all hope.

Please cite this article as: Araiz Burdio JJ, Zalba Etayo B, Suarez Pinilla MÁ. Intensivistas, perded toda esperanza. Med Intensiva. 2019;43:320–322.