Valproic acid is a broad-spectrum antiepileptic drug used in the treatment of epilepsy and commonly used in other conditions such as bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and migraine.

Valproic acid intoxication is associated with remarkable morbidity and potential life-threatening complications. Current management options for valproate toxicity are limited and often associated with challenges such as delayed elimination and increased half-life.

We describe the case of a patient in which we used meropenem as an adjunct therapy in the management of valproic acid toxicity.

In April 2023, a 59-year-old woman, with a medical history of Schizoaffective disorder and a previous suicide attempt through intentional overdose in 2004, was found by her family at home with low level of consciousness following a drug overdose. The time of ingestion was unknown.

She presented to the emergency department with a persistently low Glasgow Coma Scale of 4/15, miotic pupils, tachycardia and difficulty of breathing. The patient was administered 50 mg of activated charcoal via nasogastric tube, 0.4 mg of naloxone, and 1 mg of flumazenil. However, there was a minimal response to the latter, characterized by a flexor response of the limbs and the emission of guttural sounds upon painful stimulation. A flumazenil 0.4 mg/h continuous infusion was initiated but the Glasgow Coma Scale did not improve, leading to her prompt intubation for airway protection. She was then transferred to the Intensive Care Unit while remaining hemodynamically stable and sedated.

The initial laboratory tests showed an increased anion gap metabolic acidosis, with lactic acid concentration of 3.4 mmol/L, pH 7.33, ammonia concentration of 315.55 µg mol/L, valproic acid concentration of 503.06 µg/mL (normal range 50−100 µg/mL) and an olanzapine concentration of 175 ng/mL (normal range 20−80 ng/mL). Benzodiazepines were also detected in the urine. The patient was administered levocarnitine to prevent and reverse valproate-related metabolic disorders. A 12-lead electrocardiogram revealed an initial QTc of 464 msec, a chest X-ray indicated no signs of aspiration pneumonia. However, it was decided to begin empiric antibiotic therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid.

The patient's valproic acid concentrations subsequently decreased to 296.85 µg/mL and 282.06 µg/mL at 2 and 10 h after admission, respectively. We calculated the individual pharmacokinetics parameters using the Bayesian forecasting model that contains a population model (14–70 years) of valproic acid (Abbottbase pharmacokinetic system PKS®, Abbott Laboratories, PKS, Chicago, IL, USA). The maximum serum concentrations of valproic acid allowed in this model were 250.00 µg/mL. Accepting this adjustment, the predicted valproate serum concentrations in our patient at 36 h of admission were still above the normal range (118.15 µg/mL).

After that, it was decided to prescribe a single dose of 1 g of meropenem. Following meropenem administration, 15 h later (36 h after admission), serum valproic acid concentrations declined to 13.9 µg/mL, below subtherapeutic concentrations. Her ammonia concentration reached normal range and the patient showed increased alertness and started responding to commands. The patient was transferred out of the Intensive Care Unit on the 3rd day of hospitalization and ultimately discharged to inpatient psychiatry.

Valproic acid exhibits a complex nonlinear pharmacokinetic profile and is highly bound to albumin. The unbound fraction of valproic acid in the serum varies between 6% and 10%. However, this percentage is influenced by factors such as serum albumin concentration, serum VPA concentration, age, and the presence of end-organ failure. Therefore, relying solely on the total serum concentration of valproic acid can sometimes be misleading.1

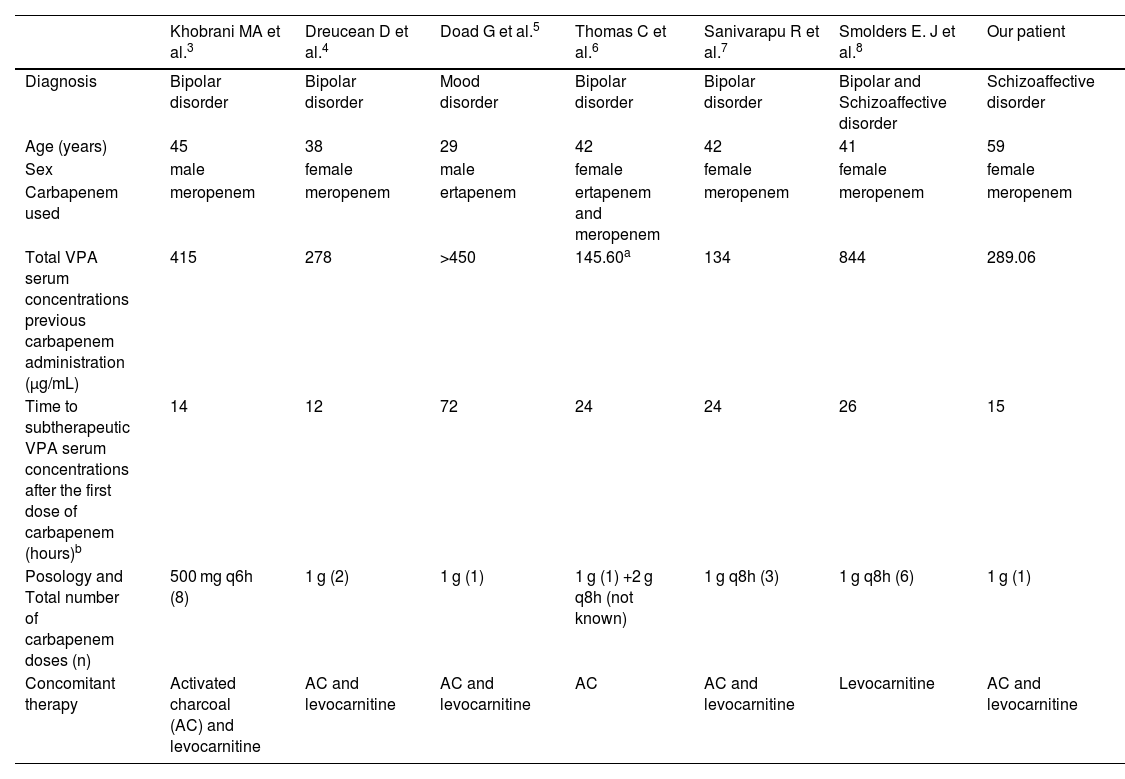

The pharmacological mechanisms underlying the interaction between valproic acid and carbapenem antibiotics, such as meropenem, are complex and not well defined. Evidence suggests that carbapenems may influence valproic acid absorption, distribution, and metabolism, leading to a rapid and pronounced reduction in serum valproate concentrations, and increasing the risk of seizures in epileptic patients.2 Because of this interaction, it is generally recommended to avoid the use of these two medications concurrently. However, based on various cases published in the literature3–8 we intentionally used a carbapenem to decrease valproic acid concentrations in our patient. Table 1 summarizes all the published studies regarding intentional use of VPA-carbapenem interaction in non-epileptic patients.

Reported non-epileptic patients with intentional use of VPA-carbapenem interaction.

| Khobrani MA et al.3 | Dreucean D et al.4 | Doad G et al.5 | Thomas C et al.6 | Sanivarapu R et al.7 | Smolders E. J et al.8 | Our patient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Bipolar disorder | Bipolar disorder | Mood disorder | Bipolar disorder | Bipolar disorder | Bipolar and Schizoaffective disorder | Schizoaffective disorder |

| Age (years) | 45 | 38 | 29 | 42 | 42 | 41 | 59 |

| Sex | male | female | male | female | female | female | female |

| Carbapenem used | meropenem | meropenem | ertapenem | ertapenem and meropenem | meropenem | meropenem | meropenem |

| Total VPA serum concentrations previous carbapenem administration (µg/mL) | 415 | 278 | >450 | 145.60a | 134 | 844 | 289.06 |

| Time to subtherapeutic VPA serum concentrations after the first dose of carbapenem (hours)b | 14 | 12 | 72 | 24 | 24 | 26 | 15 |

| Posology and Total number of carbapenem doses (n) | 500 mg q6h (8) | 1 g (2) | 1 g (1) | 1 g (1) +2 g q8h (not known) | 1 g q8h (3) | 1 g q8h (6) | 1 g (1) |

| Concomitant therapy | Activated charcoal (AC) and levocarnitine | AC and levocarnitine | AC and levocarnitine | AC | AC and levocarnitine | Levocarnitine | AC and levocarnitine |

We used meropenem as it is the most extensively described carbapenem causing this interaction.1 Nevertheless, other authors have used ertapenem with successful outcomes. Wu CC et al.9 suggest that ertapenem and meropenem have a greater effect on VPA serum concentration than imipenem/cilastatin.

A 1 g dose of meropenem was sufficient in our patient, and contrary to Khobrani MA et al.,3 we did not switch the antibiotic therapy for the treatment of aspiration pneumonia in favor of meropenem. The majority of the patients received a carbapenem course lasting more than 72 h, making it unlikely to adversely impact on antimicrobial resistance.10

Finally, it should be noted that carbapenems have been mostly used intentionally to treat valproic acid overdose in patients with low risk of seizure, and no adverse events were reported in this population. Cunningham, D et al.11 and Muñoz-Pichuante D. et al.12 reported this use in two epileptic patients (not included in Table 1), who showed no evidence of seizure activity. Further studies are needed in order to assess the safety of carbapenems in epileptic patients in this scenario.

The administration of meropenem was safe and resulted in an important reduction in serum valproate concentrations in our patient, improved clinical outcomes, and avoided the need for invasive procedures such as dialysis. The use of meropenem in the management of valproic acid toxicity holds promise and may provide a valuable addition to the current treatment strategies for this challenging condition.