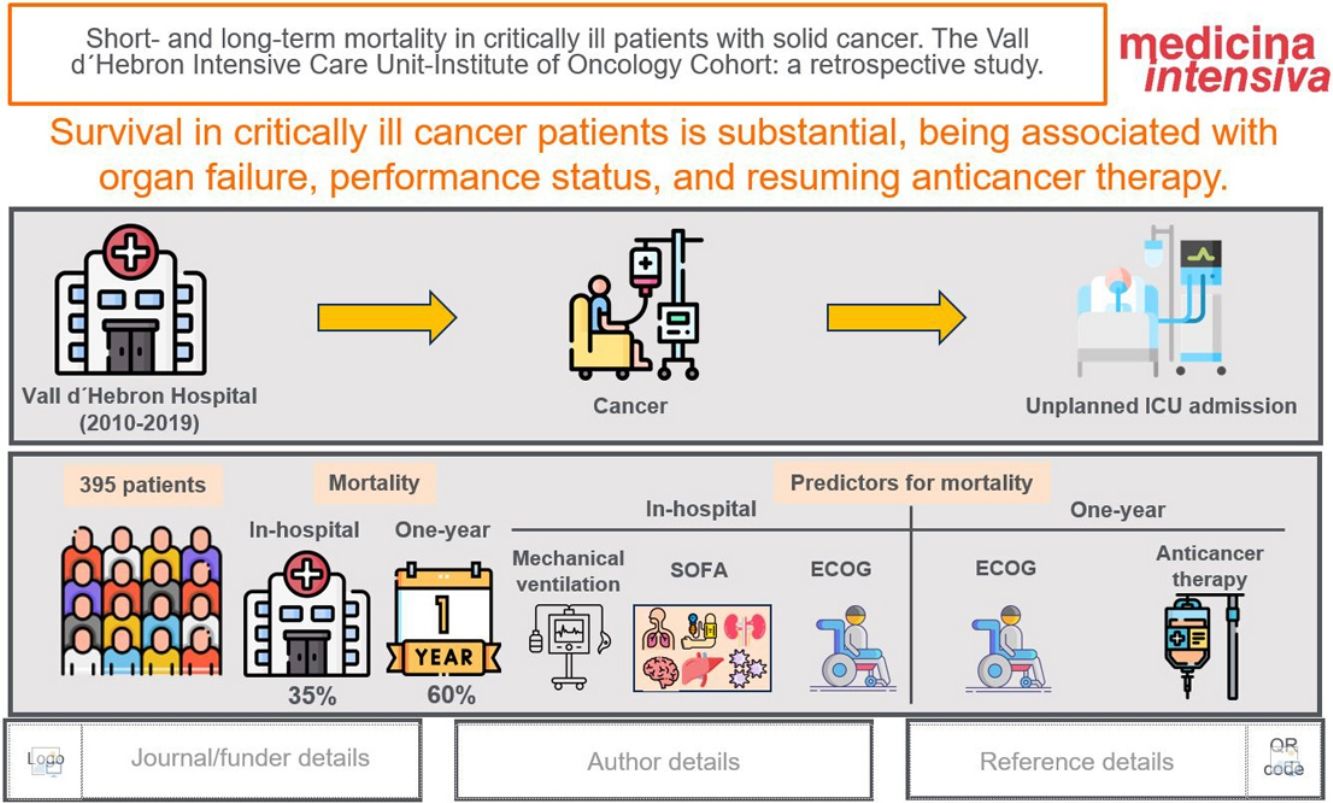

To describe in-hospital and one-year mortality and to identify prognostic variables associated with mortality.

DesignRetrospective cohort study.

SettingTertiary referral hospital in Barcelona (Spain).

PatientsConsecutive patients with solid cancer and unplanned admission to the ICU over a ten year period (2010–2019).

Main variables of interestIn-hospital mortality, one-year mortality, type of cancer, metastatic disease, ECOG, APACHE, SOFA, invasive mechanical ventilation, vasoactive drugs, renal replacement therapy.

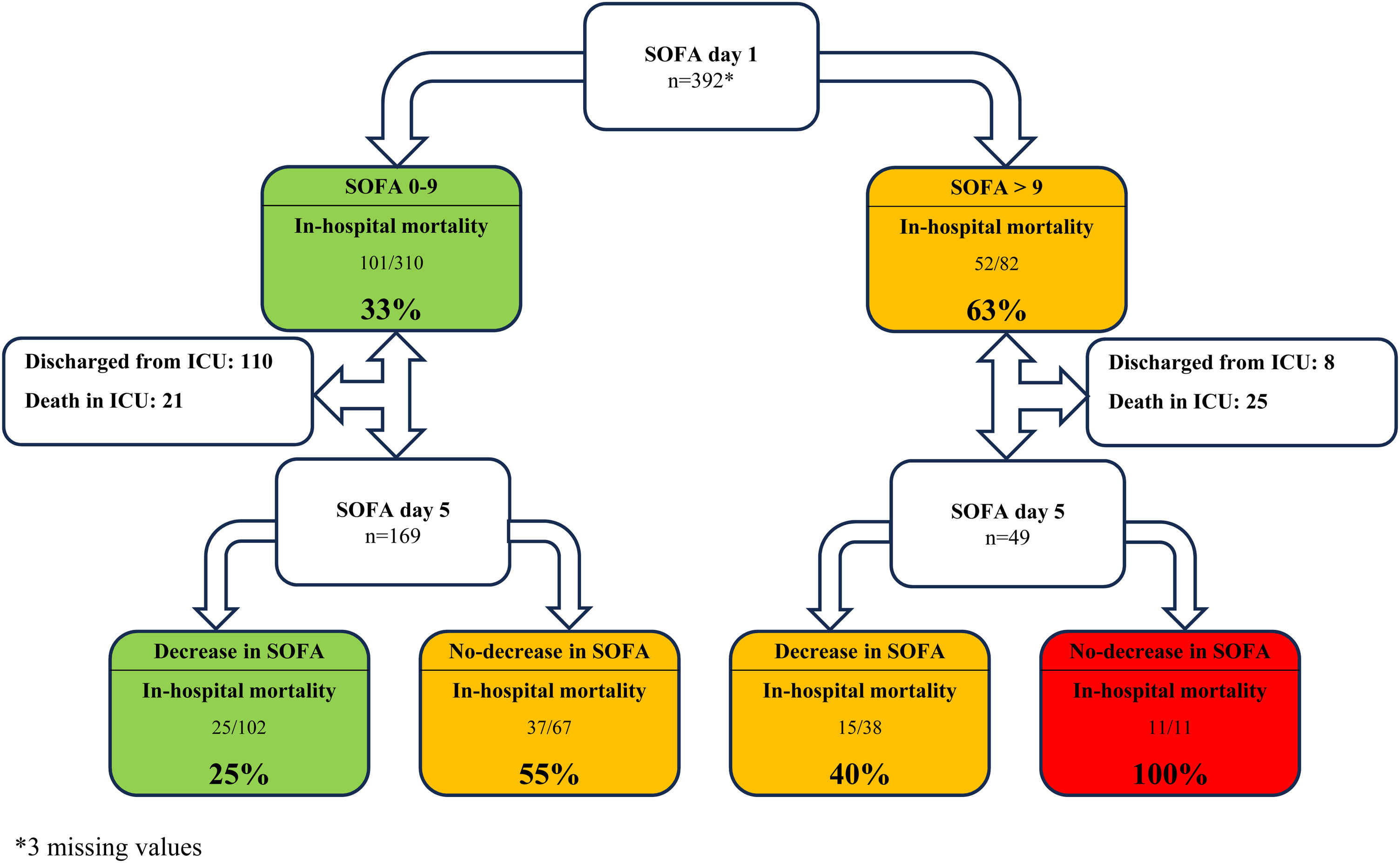

ResultsThree hundred and ninety-five patients were admitted to the ICU; 193 (48.8%) had metastatic disease, and 22 (5.9%) presented neutropenia. The median SOFA score on day 1 of ICU admission was 6 (3−9). ICU, in-hospital, and one-year mortality were 27.9% (110 patients), 39% (139 patients), and 61.1% (236 patients), respectively. A non-surgical admission, a higher ECOG, a SOFA score > 9 on day 1, a non-decreasing SOFA score on day 5, and requiring invasive mechanical ventilation were factors associated with in-hospital mortality. ECOG, inability to resume anticancer therapy, and ICU admission due to respiratory failure were associated with one-year mortality in hospital survivors.

ConclusionSurvival in critically ill solid cancer patients is substantial, even when metastatic disease exists. Short-term outcomes were associated with ECOG and organ dysfunction, not cancer per se. The prognosis of patients with a non-decreasing SOFA score on day 5 is poor, especially when the SOFA score on day 1 was >9. Long-term mortality was associated with functional status and inability to resume anticancer therapy.

Describir la mortalidad hospitalaria y al año e identificar factores pronósticos asociados a la misma.

DiseñoEstudio de cohortes retrospectivo

ÁmbitoHospital terciario de referencia en Barcelona (España)

PatientesPacientes consecutivos con neoplasia de organo sólido con ingreso no programado en UCI durante 10 años (2010–2019).

Variables de interés principalesMortalidad hospitalaria, mortalidad al año, cáncer, metástasis, ECOG, APACHE, SOFA, ventilación mecánica, drogas vasoactivas, terapias de reemplazo renal.

ResultadosTrescientos noventa y cinco pacientes ingresaron en la UCI; 193 (48.8%) tenían enfermedad metastásica y 22 (5.9%) neutropenia. El SOFA el dia 1 fue 6 (3-9). La mortalidad en UCI, hospitalaria y al año fue del 27.9% (110 pacientes), 39% (139 pacientes) y 61.1% (236 pacientes), respectivamente. Un ingreso no quirúrgico, un mayor ECOG, un SOFA > 9 el día 1, el no descenso del SOFA en el día 5 y la ventilación mecánica se asociaron con la mortalidad hospitalaria. El ECOG, no continuar el tratamiento anticanceroso y el ingreso por insuficiencia respiratoria se asociaron con la mortalidad al año.

ConclusiónLa supervivencia en los pacientes críticos con cancer es significativa, incluso en presencia de enfermedad metastásica. La mortalidad a corto plazo se asocia al ECOG y la disfunción orgánica, y no al cáncer per se. El pronóstico de los pacientes en los que el SOFA no disminuye el día 5, especialmente si el SOFA inicial era >9, es sombrío. La mortalidad a largo plazo está condicionada por el estado funcional y la continuidad del tratamiento antineoplásico.

Cancer is a major public health condition and the second cause of death worldwide. It is estimated that the incidence and mortality of cancer in 2025 will be 21.9 and 11.4 million new cases, respectively.1 Patients with solid cancer are at high risk of requiring Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission due to respiratory failure, sepsis, cancer progression with organ infiltration, and cancer therapy toxicity. More than 5% of patients with solid cancer require ICU admission within two years of cancer diagnosis.2

Over the last decades, there has been a rearrangement of the ICU admission criteria of cancer patients from highly restrictive admission policies enquiring about the benefit of ICU care for these patients to a more rational strategy based on their functional status, cancer prognosis, available therapies, and organ dysfunction.3 Solid cancer patients account for over 10% of the ICU population.4 Parallel to the increase in ICU admissions, overall mortality has significantly dropped due to new advances in oncology therapies and supportive care. However, the improvement in the prognosis of critically ill cancer patients5 has not ameliorated the significant number of patients dying in the ICU2 or having limited long-term survival6 and quality of life after hospital discharge.7

Several prognostic factors for ICU survival of cancer patients have been identified over the last two decades. These include invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV),8–10 vasoactive drugs (VAD),8 renal replacement therapy (RRT),11 poor performance status (assessed by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance status scale, ECOG-PS), multiorgan failure,12 and acute severity scores, such as the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II)10 and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA)13 scores, and Oncoscore.6 Yet, the current reliability of medical assessments in identifying patients most likely to benefit from ICU admission remains undermined.14 Accurate selection of critically ill cancer patients is challenging, with some key questions remaining unsolved: (1) Who to admit; to deliver ICU care to patients who will benefit from it, and to avoid non-beneficial or futile care, which would prolong the suffering of patients and their beloved ones; (2) How long should we provide supportive therapy during an ICU-trial without limiting chances of survival (3) How to identify patients who will have prolonged survival and resume their previous status after hospital discharge.

We aimed to describe a large cohort of critically ill patients with solid cancer admitted to the ICU of a tertiary care teaching referral hospital to evaluate the in-hospital and one-year mortality. Identifying risk factors associated with adverse outcomes will aid clinical decision-making when managing acute conditions in this challenging population.

Patients and methodsStudy designRetrospective single-center study. The manuscript was prepared according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement (Electronic Supplementary Material 1).

SettingThis study was conducted at the ICU of the Vall d’Hebron University Hospital (VHUH), a 1500-bed tertiary teaching hospital in Barcelona (Spain). The ICU department is a medical and surgical polyvalent 40-bed ICU staffed by ICU consultants on a 24/7 basis. Oncology consultants are also present at the hospital on a 24/7 model. Management of critically ill oncologic patients was based on a multidisciplinary approach, including a close collaboration between the ICU, Oncology, and Infectious Diseases consultants, leading to admission decisions, relevant management issues, and withhold-withdrawn organ support interventions. The study was approved by the VHUH Institutional Review Board (IRB) (PR (AG) 332/2022). The IRB waived informed consent due to the retrospective design of the study.

PatientsAll consecutive adult patients (≥18 years old) with active solid malignancy and unplanned ICU admission from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2019, were included in the study. Patients in complete remission for more than five years were excluded. Only the first episode was included for patients with more than one ICU admission during the study period.

Data collection and definitionsClinical data included baseline and disease-related characteristics, and patient functional status according to ECOG-PS scale15 recorded on the last follow-up visit before hospital admission. The reason for ICU admission, the requirement for organ support, and the SOFA scores16 on days 1, 3, and 5 of ICU admission were registered. A non-decreasing SOFA score on day 3 was defined as a SOFA score on day 3 equal or higher to SOFA score on day 1 of ICU admission. A non-decreasing SOFA score on day 5 was defined as a SOFA score on day 5 equal or higher to SOFA score on day 1 of ICU admission. Clinical data were obtained from the patients’ electronic medical records. Respiratory failure was defined as respiratory insufficiency requiring high-flow oxygen or non-invasive or invasive mechanical ventilation. Shock was defined as the requirement for vasoactive drugs to maintain a mean arterial pressure of ≥65 mmHg. Neutropenia was defined as a neutrophil count lower than 500/mm3.17

Primary and secondary outcomesTo describe in-hospital and one-year mortality after hospital discharge and to identify variables associated with mortality.

Statistical methodsQuantitative variables were expressed as median (interquartile range), and categorical variables as frequency or percentages. Student T-test and Mann–Whitney U-test were used to compare quantitative variables. Chi-square and Fisher’s tests were used to compare categorical variables. In-hospital and one-year mortality were the primary endpoints of the study. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p-value of <0.05 was considered for statistically significant differences. The multivariate Cox proportional-hazards model included all variables with a p < 0.1 to identify independent variables associated with in-hospital and one-year mortality in patients discharged alive. Multicollinearity was assessed by examining variance inflation factors (VIF). A non-proportionality test based on the Schoenfeld residuals was performed to assess the proportional-hazards assumption. STATA 18.0 software (StataCorp LP©, College Station, TX, United States) was employed for the statistical analysis.

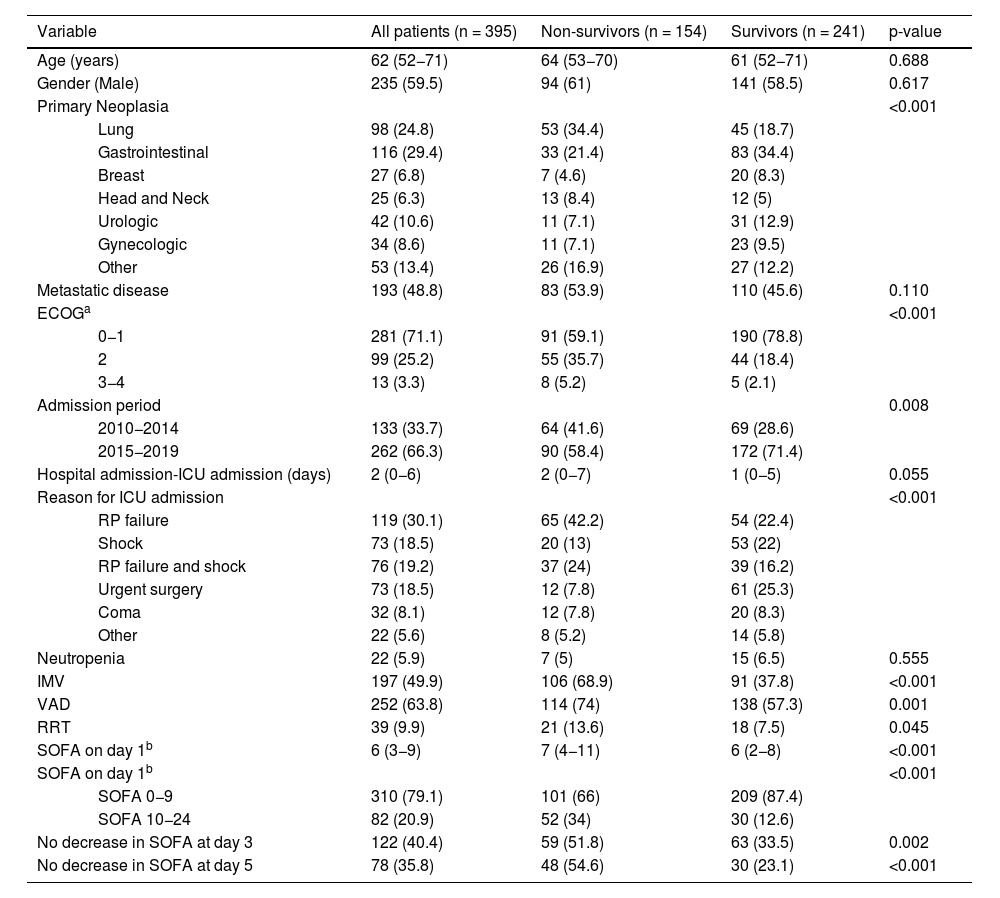

ResultsThree hundred and ninety-five patients were admitted to the ICU during the study period; 235 (59.5%) were male, with a median age of 62 (52−71) years. The most common malignant neoplasms were gastrointestinal (116; 29.4%) and lung cancer (98; 24.8%). One hundred and ninety-three (48.8%) patients had metastatic disease, and 22 (5.9%) were neutropenic. The main reasons for ICU admission were respiratory failure (119; 30.1%), shock (73; 18.5%), respiratory failure and shock (76; 19.2%), and emergent surgery (73; 18.5%). The median SOFA score on day 1 was 6 (3−9). One hundred and ninety-seven patients (49.9%) required IMV, 252 (63.8%) vasopressors, and 39 (9.9%) RRT. Two (0.5%) patients received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. Baseline characteristics during the ICU admission and differences between in-hospital survivors and non-survivors are summarized in Table 1. ICU, in-hospital, and one-year mortality were 27.9 % (110 patients), 39 % (139 patients), and 61.1 % (236 patients), respectively.

Baseline characteristics and during ICU course; differences between in-hospital survivors and non-survivors.

| Variable | All patients (n = 395) | Non-survivors (n = 154) | Survivors (n = 241) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 62 (52−71) | 64 (53−70) | 61 (52−71) | 0.688 | |

| Gender (Male) | 235 (59.5) | 94 (61) | 141 (58.5) | 0.617 | |

| Primary Neoplasia | <0.001 | ||||

| Lung | 98 (24.8) | 53 (34.4) | 45 (18.7) | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 116 (29.4) | 33 (21.4) | 83 (34.4) | ||

| Breast | 27 (6.8) | 7 (4.6) | 20 (8.3) | ||

| Head and Neck | 25 (6.3) | 13 (8.4) | 12 (5) | ||

| Urologic | 42 (10.6) | 11 (7.1) | 31 (12.9) | ||

| Gynecologic | 34 (8.6) | 11 (7.1) | 23 (9.5) | ||

| Other | 53 (13.4) | 26 (16.9) | 27 (12.2) | ||

| Metastatic disease | 193 (48.8) | 83 (53.9) | 110 (45.6) | 0.110 | |

| ECOGa | <0.001 | ||||

| 0−1 | 281 (71.1) | 91 (59.1) | 190 (78.8) | ||

| 2 | 99 (25.2) | 55 (35.7) | 44 (18.4) | ||

| 3−4 | 13 (3.3) | 8 (5.2) | 5 (2.1) | ||

| Admission period | 0.008 | ||||

| 2010−2014 | 133 (33.7) | 64 (41.6) | 69 (28.6) | ||

| 2015−2019 | 262 (66.3) | 90 (58.4) | 172 (71.4) | ||

| Hospital admission-ICU admission (days) | 2 (0−6) | 2 (0−7) | 1 (0−5) | 0.055 | |

| Reason for ICU admission | <0.001 | ||||

| RP failure | 119 (30.1) | 65 (42.2) | 54 (22.4) | ||

| Shock | 73 (18.5) | 20 (13) | 53 (22) | ||

| RP failure and shock | 76 (19.2) | 37 (24) | 39 (16.2) | ||

| Urgent surgery | 73 (18.5) | 12 (7.8) | 61 (25.3) | ||

| Coma | 32 (8.1) | 12 (7.8) | 20 (8.3) | ||

| Other | 22 (5.6) | 8 (5.2) | 14 (5.8) | ||

| Neutropenia | 22 (5.9) | 7 (5) | 15 (6.5) | 0.555 | |

| IMV | 197 (49.9) | 106 (68.9) | 91 (37.8) | <0.001 | |

| VAD | 252 (63.8) | 114 (74) | 138 (57.3) | 0.001 | |

| RRT | 39 (9.9) | 21 (13.6) | 18 (7.5) | 0.045 | |

| SOFA on day 1b | 6 (3−9) | 7 (4−11) | 6 (2−8) | <0.001 | |

| SOFA on day 1b | <0.001 | ||||

| SOFA 0−9 | 310 (79.1) | 101 (66) | 209 (87.4) | ||

| SOFA 10−24 | 82 (20.9) | 52 (34) | 30 (12.6) | ||

| No decrease in SOFA at day 3 | 122 (40.4) | 59 (51.8) | 63 (33.5) | 0.002 | |

| No decrease in SOFA at day 5 | 78 (35.8) | 48 (54.6) | 30 (23.1) | <0.001 | |

ICU: intensive care unit; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale; RP: respiratory; IMV: invasive mechanical ventilation; VAD: vasoactive drugs; RRT: renal replacement therapy; SOFA: sequential organ failure assessment.

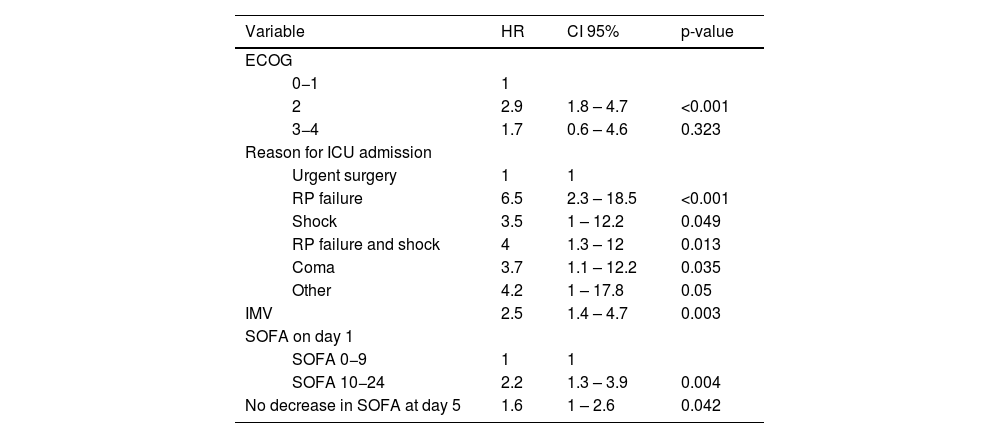

Disease-related characteristics, such as cancer type, metastatic disease, or neutropenia, were not associated with in-hospital mortality. Admission to the ICU due to a non-surgical condition, ECOG-PS scale ≥2, a higher SOFA score on day 1, a non-decreasing SOFA score on day 5, and IMV were independently associated with in-hospital mortality (Table 2). In-hospital mortality was 61% (50 patients) among the patients with a SOFA score >9 on day 1 and 32% (101 patients) among all patients. Mortality rates for patients with a non-decreasing SOFA score on day 3 and day 5 were 48.4% and 61.5%, respectively. All patients with a SOFA score >9 on day 1 and a non-decreasing SOFA score on day 5 did not survive hospital admission (Fig. 1). Depending on each subgroup, patients requiring IMV had an in-hospital mortality of 53.8%, ranging from 25.5% to 75% (Electronic Supplementary Material 2).

Cox proportional-hazards regression model of variables associated with in-hospital mortality.

| Variable | HR | CI 95% | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECOG | ||||

| 0−1 | 1 | |||

| 2 | 2.9 | 1.8 – 4.7 | <0.001 | |

| 3−4 | 1.7 | 0.6 – 4.6 | 0.323 | |

| Reason for ICU admission | ||||

| Urgent surgery | 1 | 1 | ||

| RP failure | 6.5 | 2.3 – 18.5 | <0.001 | |

| Shock | 3.5 | 1 – 12.2 | 0.049 | |

| RP failure and shock | 4 | 1.3 – 12 | 0.013 | |

| Coma | 3.7 | 1.1 – 12.2 | 0.035 | |

| Other | 4.2 | 1 – 17.8 | 0.05 | |

| IMV | 2.5 | 1.4 – 4.7 | 0.003 | |

| SOFA on day 1 | ||||

| SOFA 0−9 | 1 | 1 | ||

| SOFA 10−24 | 2.2 | 1.3 – 3.9 | 0.004 | |

| No decrease in SOFA at day 5 | 1.6 | 1 – 2.6 | 0.042 | |

ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology group scale; ICU: intensive care unit; RP: respiratory; IMV: invasive mechanical ventilation; SOFA; sequential organ failure assessment.

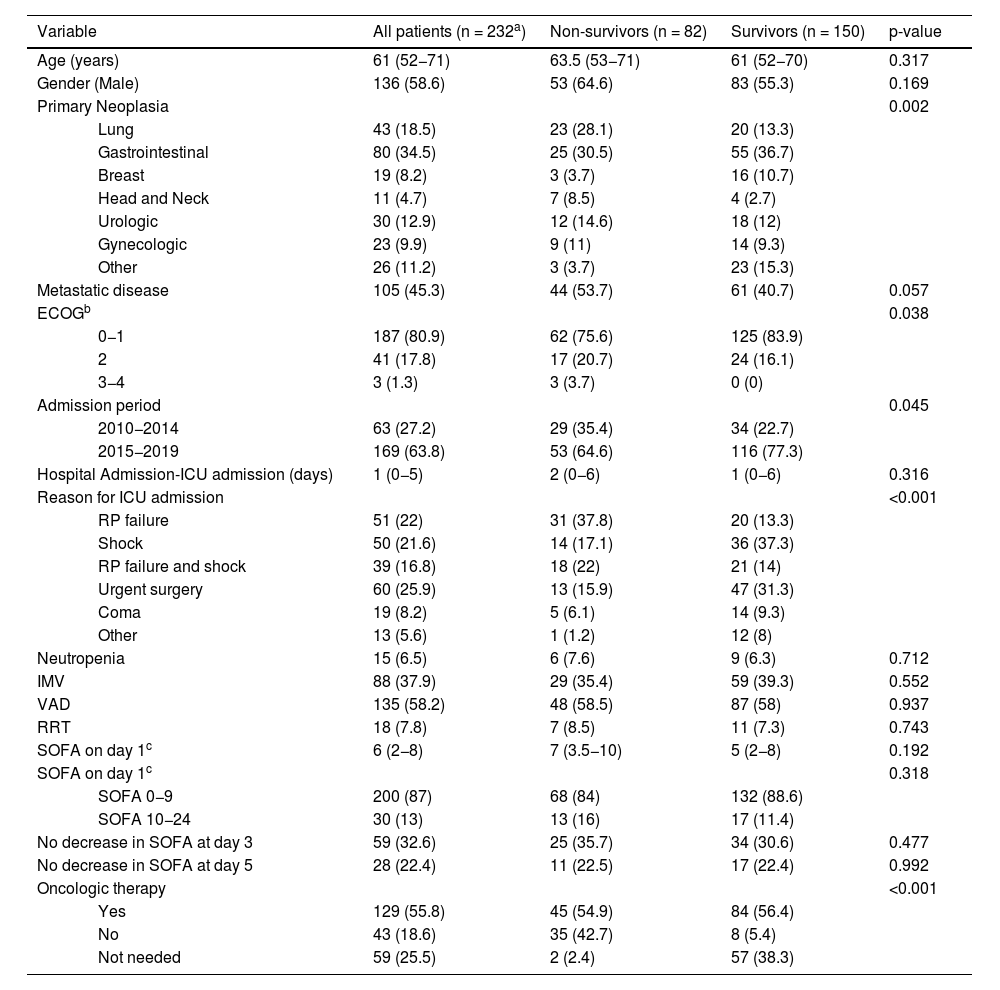

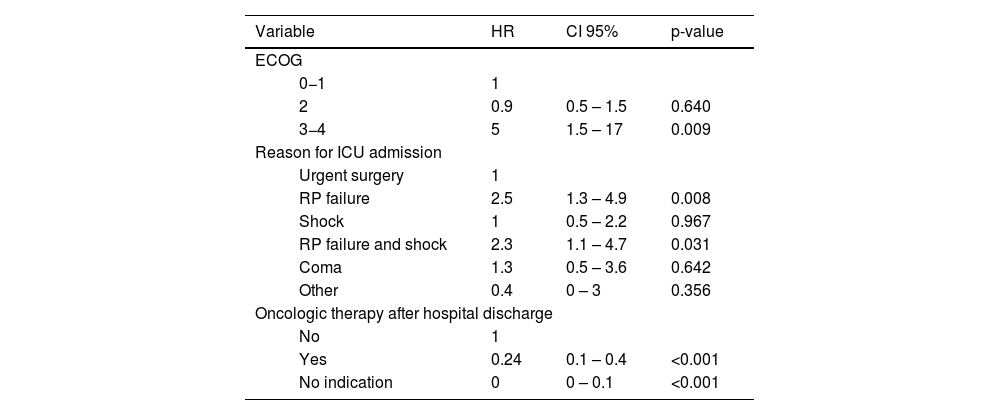

Detailed information regarding in-hospital survivors and differences between one-year survivors and non-survivors after hospital discharge are summarized in Table 3. Among in-hospital survivors, one-year mortality was higher in patients who had a poor performance status at baseline (ECOG-PS score of 3−4), who were admitted to the ICU due to respiratory failure, with or without shock, and in patients who did not receive specific oncologic therapy despite being medically indicated (Table 4).

Differences between one-year survivors and non-survivors in patients discharged alive from the hospital.

| Variable | All patients (n = 232a) | Non-survivors (n = 82) | Survivors (n = 150) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61 (52−71) | 63.5 (53−71) | 61 (52−70) | 0.317 | |

| Gender (Male) | 136 (58.6) | 53 (64.6) | 83 (55.3) | 0.169 | |

| Primary Neoplasia | 0.002 | ||||

| Lung | 43 (18.5) | 23 (28.1) | 20 (13.3) | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 80 (34.5) | 25 (30.5) | 55 (36.7) | ||

| Breast | 19 (8.2) | 3 (3.7) | 16 (10.7) | ||

| Head and Neck | 11 (4.7) | 7 (8.5) | 4 (2.7) | ||

| Urologic | 30 (12.9) | 12 (14.6) | 18 (12) | ||

| Gynecologic | 23 (9.9) | 9 (11) | 14 (9.3) | ||

| Other | 26 (11.2) | 3 (3.7) | 23 (15.3) | ||

| Metastatic disease | 105 (45.3) | 44 (53.7) | 61 (40.7) | 0.057 | |

| ECOGb | 0.038 | ||||

| 0−1 | 187 (80.9) | 62 (75.6) | 125 (83.9) | ||

| 2 | 41 (17.8) | 17 (20.7) | 24 (16.1) | ||

| 3−4 | 3 (1.3) | 3 (3.7) | 0 (0) | ||

| Admission period | 0.045 | ||||

| 2010−2014 | 63 (27.2) | 29 (35.4) | 34 (22.7) | ||

| 2015−2019 | 169 (63.8) | 53 (64.6) | 116 (77.3) | ||

| Hospital Admission-ICU admission (days) | 1 (0−5) | 2 (0−6) | 1 (0−6) | 0.316 | |

| Reason for ICU admission | <0.001 | ||||

| RP failure | 51 (22) | 31 (37.8) | 20 (13.3) | ||

| Shock | 50 (21.6) | 14 (17.1) | 36 (37.3) | ||

| RP failure and shock | 39 (16.8) | 18 (22) | 21 (14) | ||

| Urgent surgery | 60 (25.9) | 13 (15.9) | 47 (31.3) | ||

| Coma | 19 (8.2) | 5 (6.1) | 14 (9.3) | ||

| Other | 13 (5.6) | 1 (1.2) | 12 (8) | ||

| Neutropenia | 15 (6.5) | 6 (7.6) | 9 (6.3) | 0.712 | |

| IMV | 88 (37.9) | 29 (35.4) | 59 (39.3) | 0.552 | |

| VAD | 135 (58.2) | 48 (58.5) | 87 (58) | 0.937 | |

| RRT | 18 (7.8) | 7 (8.5) | 11 (7.3) | 0.743 | |

| SOFA on day 1c | 6 (2−8) | 7 (3.5−10) | 5 (2−8) | 0.192 | |

| SOFA on day 1c | 0.318 | ||||

| SOFA 0−9 | 200 (87) | 68 (84) | 132 (88.6) | ||

| SOFA 10−24 | 30 (13) | 13 (16) | 17 (11.4) | ||

| No decrease in SOFA at day 3 | 59 (32.6) | 25 (35.7) | 34 (30.6) | 0.477 | |

| No decrease in SOFA at day 5 | 28 (22.4) | 11 (22.5) | 17 (22.4) | 0.992 | |

| Oncologic therapy | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 129 (55.8) | 45 (54.9) | 84 (56.4) | ||

| No | 43 (18.6) | 35 (42.7) | 8 (5.4) | ||

| Not needed | 59 (25.5) | 2 (2.4) | 57 (38.3) | ||

ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale; ICU: intensive care unit; RP: respiratory; IMV: invasive mechanical ventilation; VAD: vasoactive drugs; RRT: renal replacement therapy; SOFA sequential organ failure assessment.

Cox proportional-hazards regression model of variables associated with one-year mortality in hospital survivors.

| Variable | HR | CI 95% | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECOG | ||||

| 0−1 | 1 | |||

| 2 | 0.9 | 0.5 – 1.5 | 0.640 | |

| 3−4 | 5 | 1.5 – 17 | 0.009 | |

| Reason for ICU admission | ||||

| Urgent surgery | 1 | |||

| RP failure | 2.5 | 1.3 – 4.9 | 0.008 | |

| Shock | 1 | 0.5 – 2.2 | 0.967 | |

| RP failure and shock | 2.3 | 1.1 – 4.7 | 0.031 | |

| Coma | 1.3 | 0.5 – 3.6 | 0.642 | |

| Other | 0.4 | 0 – 3 | 0.356 | |

| Oncologic therapy after hospital discharge | ||||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 0.24 | 0.1 – 0.4 | <0.001 | |

| No indication | 0 | 0 – 0.1 | <0.001 | |

ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ICU: intensive care unit; RP: respiratory.

In this retrospective study, we observed a 39% in-hospital and 61% one-year mortality in critically ill cancer patients admitted to the ICU. Admission to treat a medical condition, poor functional status, the requirement of IMV, a high SOFA score on day 1, and a non-decreasing sofa score on day 5 were associated with in-hospital mortality. Cancer-related characteristics, such as type of cancer, the presence of metastases, or neutropenia, were not associated with outcomes. One-year mortality after ICU discharge was higher in patients with an ECOG-PS scale of 3−4, admitted for respiratory failure, and those unfit to continue receiving specific oncologic therapy after hospital discharge. Most patients in this cohort had advanced cancer requiring organ support, especially IMV.

Although the severity of illness was significant among the patients included in our cohort, in-hospital mortality was in the lower range of previously published studies.6,12,13,18,19 Improvements in the prognosis of critically ill cancer patients during the last decade can partially explain this finding.5 The inclusion of surgical patients, close collaboration between oncologists and intensivists in our institution, and an admission policy limiting the admission of patients with a poor baseline performance status are well-known factors that previously were related to better outcomes.4,20,21 Besides, most patients were included during the second half of the study period. This likely reflects global changes in admission policies for this population over the last decade,5 given that no significant adjustments were observed at the institutional level during those years.

Baseline performance status is a decisive prognostic factor to consider in critically ill oncologic patients. ECOG-PS scale has been classically employed to evaluate patients’ functional capacity for chemotherapy and predict mortality in critically ill cancer patients.21,22 In the present study, patients with an ECOG-PS scale of 2 had higher mortality than those with a scale of 0−1. We did not observe such association in patients with scales of 3−4 as expected, probably due to a lack of power, given that those patients were infrequently admitted to the ICU. In our study, baseline ECOG-PS recorded at the last follow-up visit prior to hospital admission was employed. This approach could represent a limitation, as ECOG-PS might have changed between that time and the onset of acute illness, potentially impacting our findings. Similarly, patients admitted for a medical reason had higher mortality, consistent with previous reports.4,10

Despite improvements in the prognosis of critically ill cancer patients, the need for invasive mechanical ventilation is one of the classical milestones in clinical decision-making, being one of the most powerful predictors of ICU and in-hospital mortality.5,8,10 Similar to a double-edged sword, it can be life-saving in patients who fail to improve after a trial of non-invasive respiratory support. However, it can prolong suffering for patients and their relatives when weaning from the ventilator is delayed, prolonged, or impossible. In this cohort, overall mortality reached 53.8%, which aligns with recent reports and far from the >90% mortality described earlier in the 90’s.5 Still, the in-hospital mortality rate in patients requiring IMV was heterogeneous, exceeding 70% in specific subgroups. The decision about intubation in this scenario is complex. It should be individualized, depending on the baseline performance status, the prognosis of underlying neoplasm, the number and severity of organ failures, and patients’ preferences being managed under a multidisciplinary approach.23

The association between the risk of mortality and SOFA score on day 1 of ICU admission was previously reported in patients with hematological malignancies,22 hematopoietic stem cell transplantation,24 mixed populations,25 lung cancer26 and solid cancer patients septic shock.9 In the present study, the mortality risk of patients with a SOFA score >9 on day 1 almost doubled compared with other patients in the cohort. This finding suggests that an earlier ICU admission before organ failure develops could be of benefit, as indicated by previous studies.27,28 On the other hand, we cannot rule out that a higher SOFA score could reflect the irreversibility of organ failures despite providing critical care management during the first 24 h of ICU admission. Likewise, trends in SOFA score were associated with mortality in patients with hematological malignancies.24,29–31 This finding could be helpful for decision-making during an ICU trial, in which beneficial care is pursued, trying to avoid unnecessarily prolonged or futile organ support in patients with limited life expectancy.32

Establishing an optimal length for an ICU trial is challenging.3 In a previous study, including hematological and solid cancer patients,32 at least 6 days would be needed for establishing an adequate prognosis. Conversely, Schrime et al.25 reported that a 1–4 day trial might be sufficient for patients with solid tumors. In our study, survival was significant despite a non-decreasing SOFA score on day 3 and day 5, excluding those with a SOFA score higher than 9 on day 1 and a non-decreasing SOFA score on day 5, whose prognosis was dismal. These findings suggest that longer periods of time would be necessary to determine an adequate prognosis during an ICU-trial, although this hypothesis requires validation in future studies. Decision-making should not rely on any single predictor when considering these findings, and clinical judgment should prevail.

Long-term survival after ICU admission is often uncertain in cancer patients admitted to the ICU, with 30−58% of patients dying one year after hospital discharge.7,18,22,28,33–36 One-year mortality was in the lower range in our cohort, partly explained by the appearance of less toxic and more effective anti-cancer therapies.18 As consistently reported, we observed that patients with poor functional status and patients unable to resume oncologic therapy, if needed, had worse outcomes.37–39 Patients admitted for respiratory failure management, with or without shock, had higher one-year mortality than those admitted after urgent surgery. This can reflect the impact of organ dysfunction beyond the ICU, in concordance with former reports on respiratory failure associated with high long-term mortality in post-ICU cancer patients.6,40

Some limitations are inherent to the nature of the study, which limits its applicability in scenarios with a different case-mix population. Our results should be interpreted with caution, given that changes in ICU management during the period of inclusion (ten-year period) could also have influenced the results of this study. However, the present study is one of the largest research works, including short and long-term outcomes in a homogeneous population of solid cancer patients and unplanned ICU admission. This report provides useful information for clinical decision-making and generates hypotheses that could be demonstrated in future prospective multicentric trials.

In summary, short- and long-term survival is significant in critically ill patients with solid cancer, especially those with good PS. Patients requiring IMV had higher mortality, though around 50% were discharged alive. Thus, ICU admission and IMV should be considered on a case-by-case basis and under a multidisciplinary approach. SOFA score on day 1 was associated with mortality, suggesting that these patients could benefit from an earlier admission before established multiorgan failure. Similarly, patients with a non-decreasing SOFA score on day 5 had higher mortality, especially the subset of patients with a higher SOFA score on day 1. This information could be useful for preventing the delivery of prolonged non-beneficial care. However, a holistic assessment should prevail, as survival was significant in those with lower severity of illness at admission despite presenting a non-decreasing SOFA score on day 5. Long-term outcomes were associated with a poor baseline PS and an inability to continue anti-cancer therapy.

Consequently, when deciding on ICU admission of a cancer patient, we should consider the probability of being discharged alive and the likelihood of resuming specific anti-cancer therapy. Similarly, patients admitted for respiratory failure had higher one-year mortality than others, suggesting a long-term impact of respiratory failure beyond the ICU. This finding raises the hypothesis that these patients could benefit from a closer follow-up and rehabilitation process, which contributes to restoring organ function and maximizes the chances of resuming anti-cancer therapy.

ConclusionsSurvival in critically ill solid cancer patients is substantial, even when metastatic disease exists. Performance status is a decisive factor in clinical decision-making associated with short- and long-term mortality. Short-term outcomes are not associated with cancer per se but with the presence and severity of organ dysfunction, encouraging clinicians to admit patients to ICU before overt organ failure is established. A non-decreasing SOFA score on day 5, especially if the SOFA score on day 1 is >9, is a valuable indicator for patients unlikely to benefit from ICU care. Measures that contribute to restoring organ function after ICU admission and maximizing resuming anticancer therapy would impact long-term prognosis.

CRediT authorship contribution statementCDL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. AGR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. AP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. JR: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. EPPM: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. AA: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. DP: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. NS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. IRC: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. EE: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. RF: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Ethics approval and consent to participateThis study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the VHUH Institutional Review Board (IRB) (PR (AG) 332/2022). The IRB waived informed consent due to the retrospective design of the study.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processThe authors declare that they did not use artificial intelligence tools in the elaboration of this manuscript.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from a funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materialsThe dataset generated or analyzed during the current study is not publicly available due to ethical committee restrictions. Data might be available from the correspondent author upon reasonable request, provided the ethical committee approves data sharing.

We would like to thank Vanessa Casares, Anna Casas, and Jordi Canals, research staff from the Intensive Care Department of the Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, for their support.