The clinical practice guidelines on the management of intensive care unit (ICU) admissions recommend that the selection of patients should be based on a potential benefit,1 assigning the lowest priority to those patients who are “too well” or “too serious” to be able to benefit from the healthcare provided at the ICU.1 However, Chen et al.2 showed that the percentages of high and low risk of patients admitted to ICUs varied among different hospitals showing a lack of consensus on what patients benefit the most from their ICU admission.

The lack of beds at the ICU is another factor that justifies the refusal to hospitalize low-risk patients. Partly it is because of this that intermediate care units have been created to provide healthcare to low-risk patients in a more cost-effective scenario. However, a recent study suggests that critically ill patients may fare worse at low-intensity ICUs compared to high-intensity ICUs.3

During an ICU admission, the risk of a patient is usually defined by his severity scores.4 These severity scores are updated on a regular basis in order to achieve a better calibration of his response to therapy. However, even in the most recent models, the relation between predicted mortality and observed mortality are evenly distributed along the degree of severity.5

A study of 150,000 patients with medical diagnoses of low risk associated the ICU admission of these patients to more invasive procedures and higher costs with no significant differences of mortality.6

Given the tendency towards lower ICU-acquired complication rates, basically catheter-related infections and pneumonia, our hypothesis is that low-risk patients can benefit from ICU admissions similar to high-risk patients.

We retrospectively reviewed the 2009–2015 clinical database from the 14-bed mixed medical–surgical ICU at our university hospital. Our ICU accepts patients who require complete ICU therapies, but it also accepts intermediate-level patients. Also, our ICU is a coronary unit and stroke unit. However, our hospital is not accredited to do neurosurgery, cardiac surgery, or transplants.

The ICU clinical database includes data collected at admission (administrative data, comorbidities and severity score [SAPS3]), during the ICU stay (procedures, complications and limitation of life support treatment – LLST) and at ICU discharge (length of the ICU the stay and patient's state at discharge). The length of the hospital stay, and the patient's state at hospital discharge were obtained from the hospital database.

For statistical analysis purposes, the categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages and compared using the χ2 test. Continuous variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation and compared using the Student's t test. We stratified the population into deciles of mortality risk at admission and then compared it to the actual hospital mortality rate.

The study spans through a period of seven years and is characterized by a homogeneous case-mix in hospital admissions where the ICU admission criteria remained invariable. Four thousand nine hundred and seventeen (4917) patients were admitted (average age 65.2±16.5 years; 64% males). The average length of the ICU stay was 4.6±7.1 days and the average length of the hospital stay was 14.1±18.8 days. Mortality risk (SAPS3) at admission was 27.8±23.9% and 810 (16.5%) patients died at the ICU or at the ward after being discharged from the ICU which led to a standardized mortality ratio of 0.59±0.04.

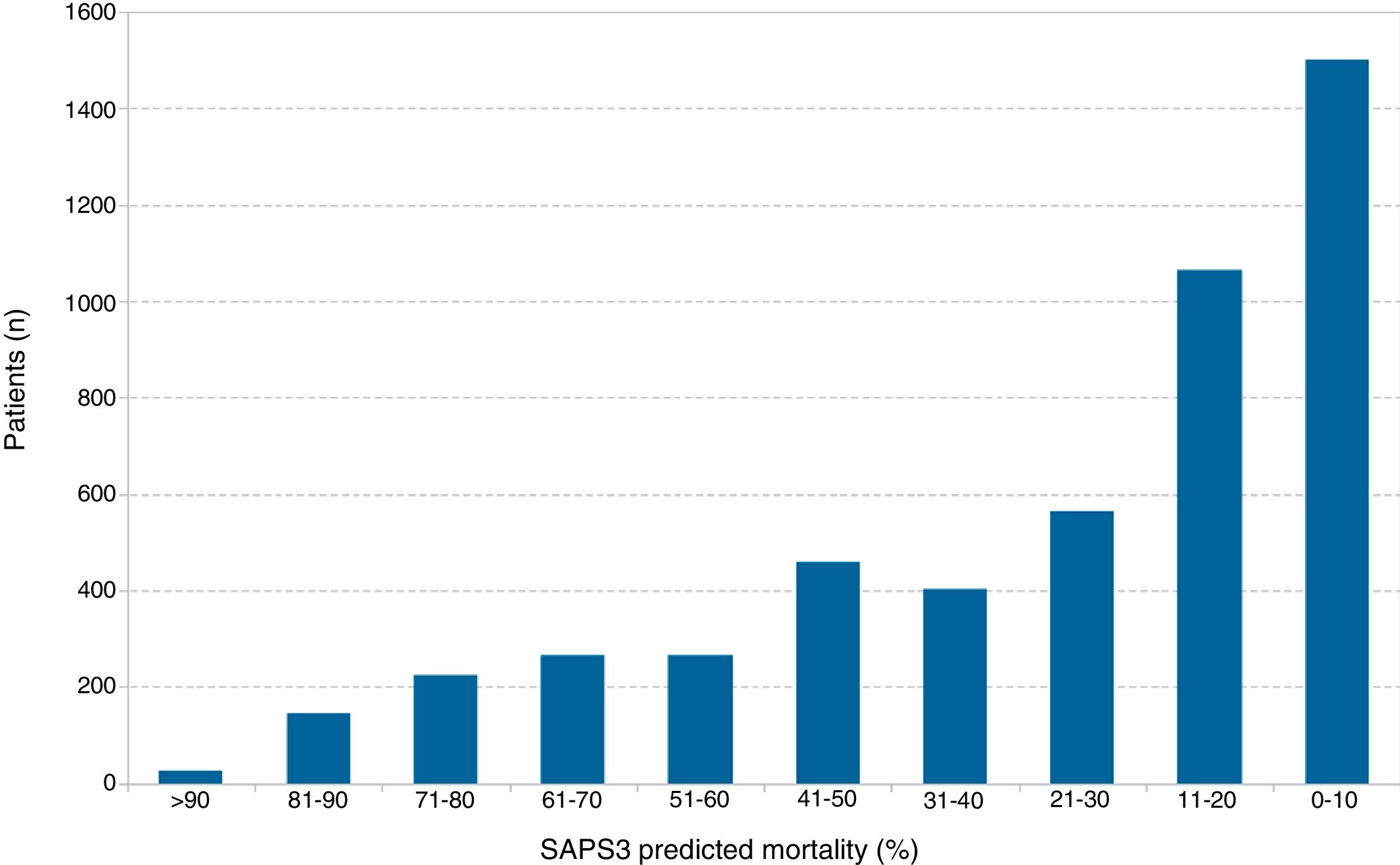

When patients were stratified into deciles of SAPS3 risk, a biased population was seen with a higher percentage of low-risk patients (risk<10%) compared to high-risk patients (risk>50%) (1499 [30.5%] vs 929 [18.9%]) (Fig. 1). The length of the ICU stay was not homogeneous either (low risk: 2.9±4.2 days vs high risk: 6.6±9.7 days, P<.001).

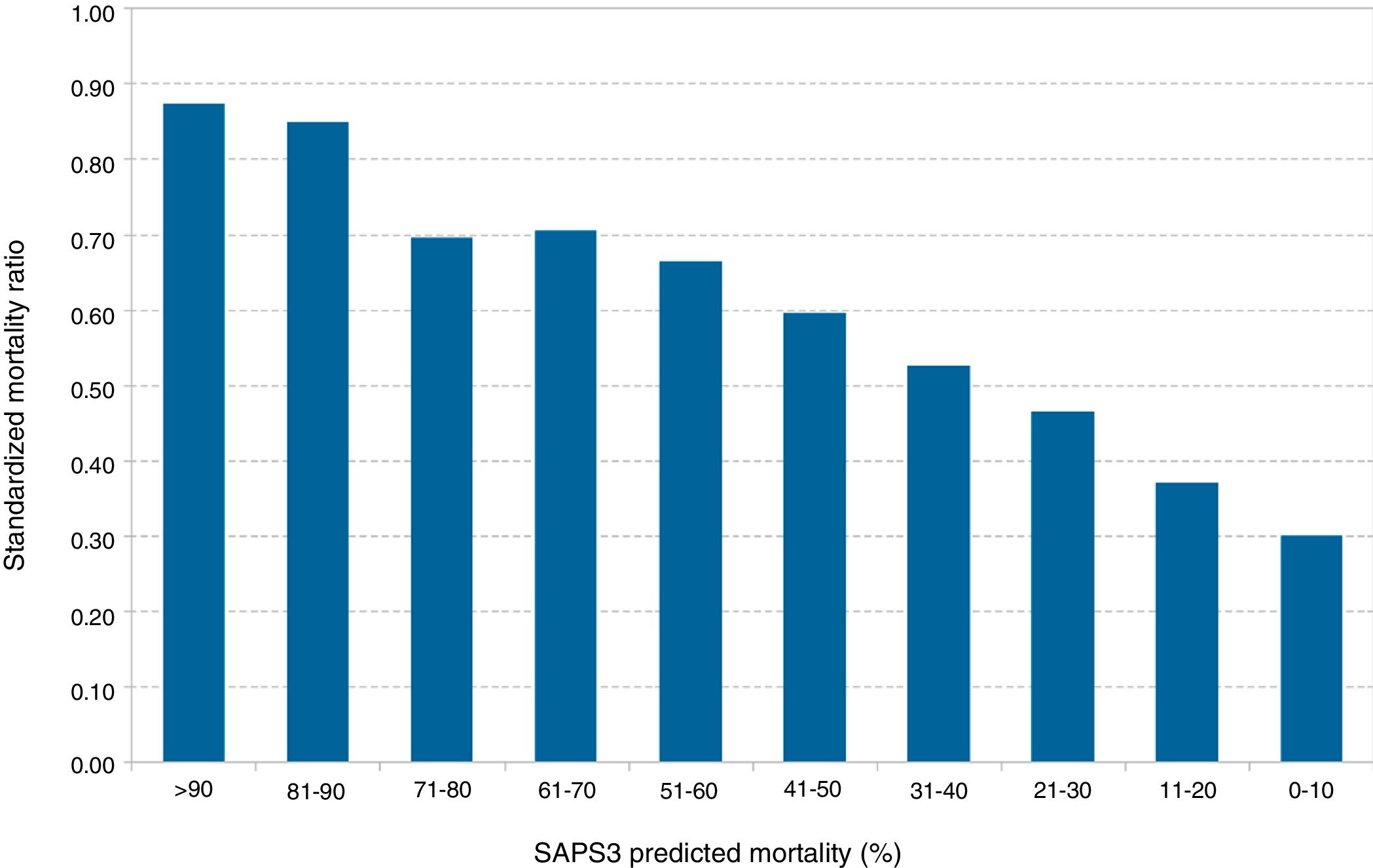

Fig. 2 shows that the standardized mortality ratio was also distributed non-homogeneously dropping gradually with respect to lower deciles of the SAPS3, from 0.87 for SAPS3>90% to 0.30 for SAPS3<10%.

This study found that low-risk patients not only were not hurt by their ICU admission, but that the survival benefit of low-risk patients was proportionally greater compared to high-risk patients.

Our analyses are based on the predictive value of SAPS3 at admission. The original SAPS3 was adapted to predict mortality in every level of risk while taking into consideration the geographical and developing area of the world where the patient received healthcare.5 For this reason, part of our population's survival advantage compared to the predicted mortality rate may be due to the cumulative effects of not calibrating this tool across the years as it has already been proven.7 However, none of the studies that evaluated this problem found that this error in the calibration affects differently based on the level of predicted risk.4,7

Our period of observation was not long enough to be able to show time-dependent effects over the standardized mortality ratio. On the other hand, some patients spent one or more days at the ICU waiting to be hospitalized, meaning that the survival benefit may be associated with the improvement reported and with admissions at semi-intensive care units,8 yet former studies do not suggest a greater benefit for low-risk patients.

Another problem here is the economic burden involved when admitting low-risk patients to an ICU. We do not have direct data on costs, but most studies suggest that the key factor here is the much shorter length of the ICU stay9,10 of low-risk patients. We can only speculate whether there would be an equivalent survival advantage for low-risk patients in less expensive ICUs, such as semi-intensive or “low intensity” units.3

Our study suggests that ICU admissions involve survival benefits for low-risk patients as well, which makes them eligible for admission too.

AuthorsPerson responsible for this paper, its concept and design: RF.

Analysis and interpretation: RF, JMA, IC, OR, SC, and CS.

Manuscript writing: RF.

Please cite this article as: Fernandez R, Alcoverro JM, Catalán I, Rubio O, Cano S, Subirà C. ¿Se debe restringir el ingreso en cuidados intensivos solo a los pacientes más graves? Med Intensiva. 2019;43:382–384.