Guaranteeing a venous access in critically ill COVID-19 patients may pose a challenge to intensivists who need to strike a balance between optimizing resources and time, minimizing personnel exposure and avoiding equipment contamination/environmental viral spread, while assuring a quick, safe and durable venous line.

A recent publication showed that vascular access practices differ between COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients.1 Uncommon venous cannulations, such as the catheterization of the great saphenous vein or the popliteal vein (non-central venous lines), have also gained frequency among critically ill patients with COVID-19.2

As a quick, proven, feasible, efficacious and safe venous line, the midline venous catheter (MC) appear as an interesting option in the current outbreak. Gidaro et al.1 revealed that in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, 38.5% of the venous lines were MC; however, many of these cannulations were not performed in critical care patients.

Long dwell-times and low rates of catheter related bacteremia are the main advantages of MC,3 while some concerns exist regarding the reported high rates of venous thrombosis.3,4 Other complications include catheter dislodgement, occlusion, phlebitis and infiltration.3 Interestingly, infusing several irritant medications common to critical care patients such as vasopressors proved to be safe.5

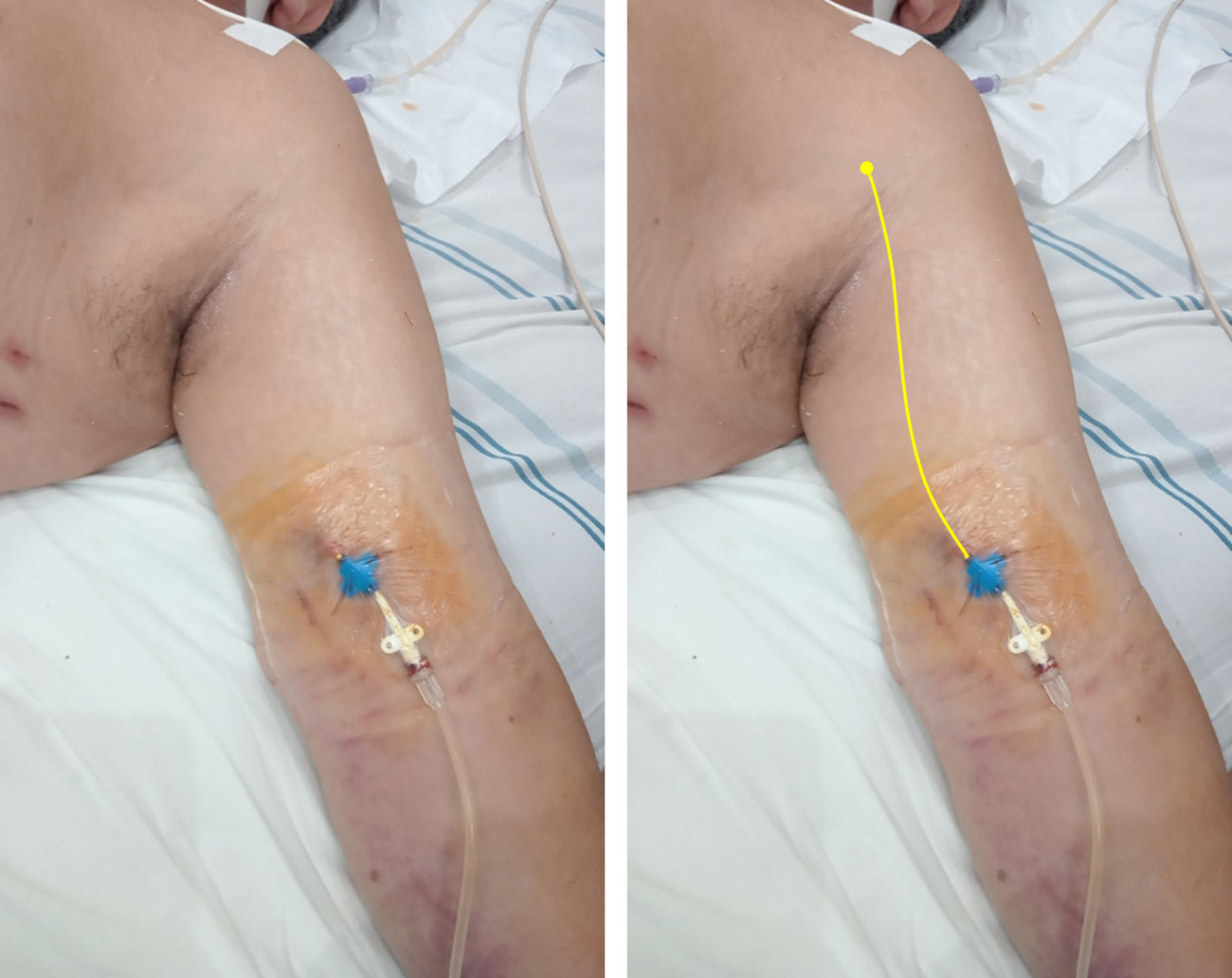

In short, a MC averages 20cm in length and is typically placed under ultrasound guidance in the basilic or cephalic vein of the upper arm, or in a brachial vein; the catheter tip lies in the axillary region (axillary vein)6 (Fig. 1). To pass the catheter, using the Seldinger technique is required, while radiographic control is unnecessary.

Midline catheter (16G, 20cm in length) placed in the left arm of a critical care patient with COVID-19. On the right, a yellow line is illustrating the catheter path and the position of the tip in the axillary region (axillary vein). Modified from Blanco P. The midline venous catheter. Rev Hosp Emilio Ferreyra. 2021; 1(1):e3–e9. http://revista.deiferreyra.com/index.php/RHEF/article/view/31/89. (CC BY 4.0).

As the preferred approach in our intensive care unit (ICU) dedicated to COVID-19 patients, we insert MC instead of central catheters, always using ultrasound (US) guidance by staff intensivists skilled in ultrasound-guided cannulations.

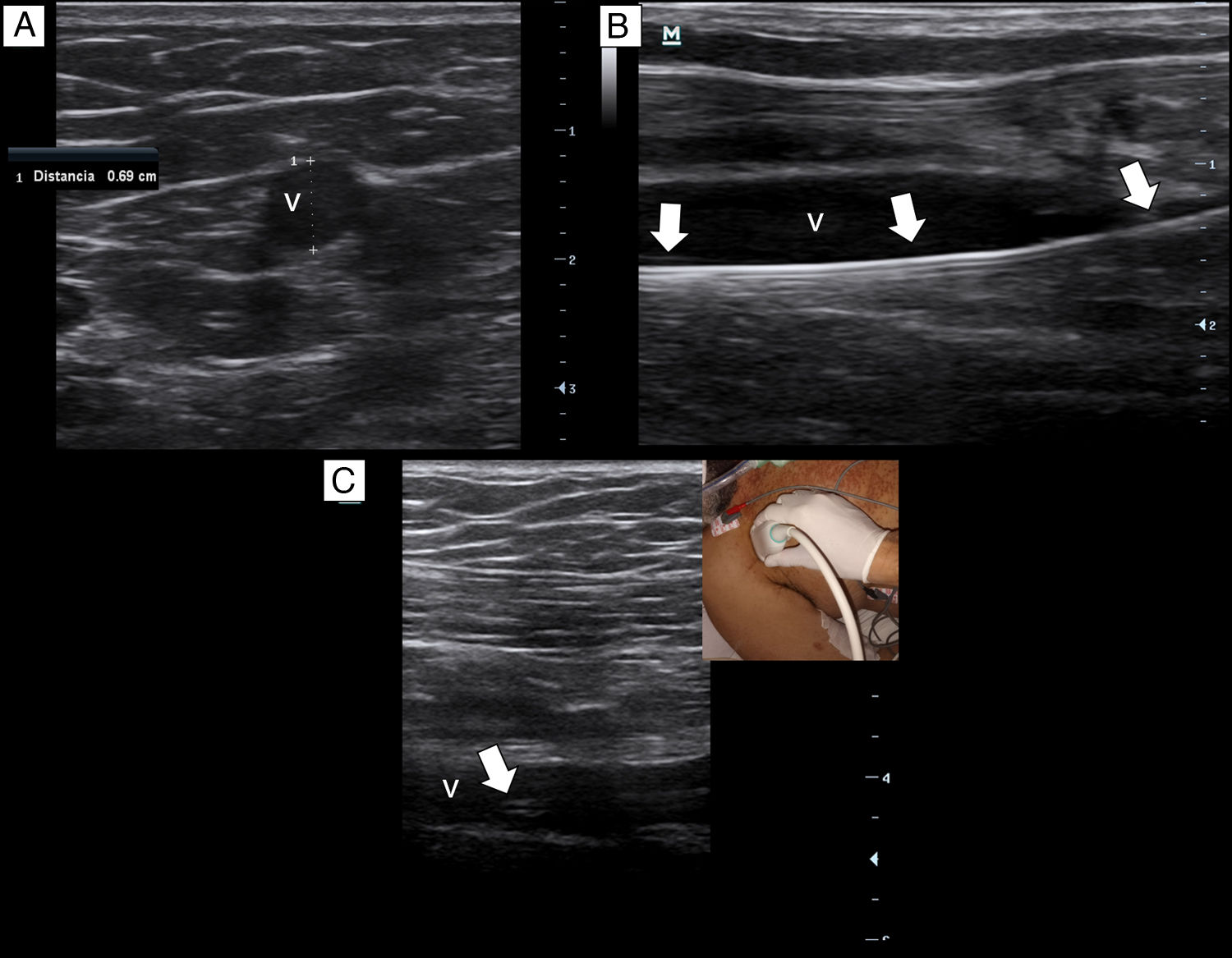

Briefly, with a tourniquet high in the arm, we scan for target veins based on their patency, size and depth. Patent veins with a diameter ≥4mm and closest to the skin are only considered for cannulation (Fig. 2a). Basilic vein of the arm, a brachial vein or the cephalic vein of the arm typically fulfill these criteria. For catheter placement, aseptic technique and maximal sterile barrier precautions are used. We perform the in-plane technique in all the cannulations. As in our institution there are no available kits of MC, we replace it by a central venous catheter kit (polyurethane-based, 14-16G, 20–30cm in length catheters). After inserting the needle by dynamic ultrasound guidance, blood is freely aspirated and guidewire is then passed, we confirm that the latter is in the vein lumen before passing the dilator (Fig. 2b). When introducing the catheter, to avoid advancing in the subclavian vein, we check by ultrasound that the catheter tip lies in the thoracic tract of the axillary vein (Fig. 2c). To avoid dislodgement of the catheter, we secure it by suturing both the holding clips and the hub to the skin.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Comité de Ética Instituto Médico Platense (CEDIMP – 25 Aug 2021).

From November 2020 to July 2021, corresponding to the first and second coronavirus waves in Argentina, a total of 60 MC were placed in 52 patients (4 in prone position). First pass success was 98% and overall success rate was 100%. There were no arterial punctures, catheter dislodgement, occlusion or phlebitis. Infiltration was observed with one catheter (1.6%). Catheter dwell time ranges from 2 to 25 days, catheter related bacteremia was 1.5 per 1000 catheter days and catheter-related thrombosis was 3.1 per 1000 catheter days. Vasopressors, such as norepinephrine at doses up to 3μg/kg/min, were infused without observing complications (e.g., extravasation and soft tissue necrosis). Minor hematomas without clinical significance were seen around the insertion site in most patients.

Based in our ongoing experience, ICU physicians may consider MC as the preferred venous line in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Placement of MC is quick and does not require radiographic control, the latter reducing the personnel involved and avoiding equipment contamination/viral spread. We notice that the overall performance of MC is equivalent to that of central catheters, with a seemingly safest profile. Of note, full competences in US-guided cannulations are mandatory to obtain the best insertion line outcomes. Last but not least, we humbly ask ourselves whether this MC insertion approach could also be replicated in non-COVID-19 patients. While it sounds reasonable, further studies are needed to answer this question, particularly when a similar POCUS expertise is achieved among intensivists.