primary objective: to improve the FPS rates after an educational intervention. Secondary objective: to describe variables related to FPS in an ED and determine which ones were related to the highest number of attempts.

Designit was a prospective quasi-experimental study.

Settingdone in an ED in a public Hospital in Argentina.

Patientsthere were patients of all ages with intubation in ED.

Interventionsin the middle of the study, an educational intervention was done to improve FPS. Cognitive aids and pre- intubation Checklists were implemented.

Main variables of interestthe operator experience, the number of intubation attempts, intubation judgment, predictors of a difficult airway, Cormack score, assist devices, complications, blood pressure, heart rate, and pulse oximetry before and after intubation All the intubations were done by direct laryngoscopy (DL).

Resultsdata from 266 patients were included of which 123 belonged to the basal period and 143 belonged to the post-intervention period. FPS percentage of the pre-intervention group was 69.9% (IC95%: 60.89–77.68) whereas the post-intervention group was 85.3% (IC95%: 78.20–90.48). The difference between these groups was statistically significant (p=0.002). Factors related to the highest number of attempts were low operator experience, Cormack-Lehane 3 score and no training.

Conclusionsa low-cost and simple educational intervention in airway management was significantly associated with improvement in FPS, reaching the same rate of FPS than in high income countries.

objetivo principal: mejorar la tasa de éxito de intubación luego de una intervención educativa. Objetivo secundario: describir las variables asociadas con el éxito en el primer intento (EPI) y determinar cuáles se relacionaron con mayor número de intentos.

Diseñoestudio prospectivo cuasi-experimental. Ámbito: realizado en un SE de un Hospital público de Argentina.

Pacientesse incluyeron todos aquellos pacientes intubados en el SE en el período de estudio.

Intervenciónen la mitad del estudio, se realizó una intervención educativa, se implementaron ayudas cognitivas y listas de verificación preintubación. Todas las intubaciones se realizaron por laringoscopia directa.

Variables de interés principalesexperiencia del operador, número de intentos de intubación, criterios de intubación, predictores de vía aérea difícil, grado de Cormack, dispositivos facilitadores utilizados, complicaciones y los signos vitales antes y después de la intubación.

Resultadosse incluyeron datos de 266 pacientes de los cuales 123 pertenecían al período basal y 143al período postintervención. El porcentaje de éxito del grupo preintervención fue del 69,9% (IC95%: 60,89-77,68) mientras que el grupo postintervención fue del 85,3% (IC95%: 78,20-90,48). La diferencia entre estos grupos fue estadísticamente significativa (p=0,002). Los factores relacionados con el mayor número de intentos fueron la baja experiencia del operador, el grado de Cormack-Lehane 3 y la falta de capacitación.

Conclusionesuna intervención educativa simple y de bajo costo en el manejo de la vía aérea se asoció significativamente con la mejora en el éxito del primer intento de intubación, alcanzando los porcentajes de los países de altos ingresos.

Emergency intubation is one of those situations in medicine that quick decisions must be made about critically ill patients who may die quickly. The complications of tracheal intubation in an emergency are multifactorial and have a direct impact on the patient's prognosis. The type of pathology leading to airway protection, oxygenation, hemodynamic status of the patient, difficult anatomic parameters of the airway, type of intubation sequence, different operator training, and human factors have been associated with complications and poor outcomes.1–6

The more intubation attempts that are made in an emergency, the more often adverse effects and complications occur,7–9 so the greatest effort should be made to ensure that the first attempt is the best intubation attempt.

Nowadays, the main reference for FPS rate in emergencies ED is 84% in high-income countries.10,11 Our study group has recently published an observational study of 241 patients in which that rate was 78%.12

A quasi-experimental prospective before-after study is presented. It was hypothesized that the percentage of FPS would increase after a simple and low-cost intervention between two instances (primary objective). It also aimed to describe some variables related to the highest number of intubation attempts (secondary objective).

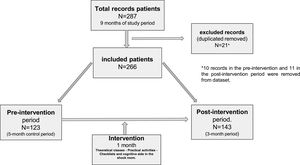

MethodStudy design and time periodThe study was developed in 9 months, between September 2020 and June 2021. There were 3 phases: a baseline phase (pre-intervention), a five months duration phase, an intervention phase of one-month duration in which specific training in airway management was provided, and a post-intervention phase of three months duration. This study was conducted during the first waves (pre-intervention) and second waves (post-intervention) of the COVID-19 pandemic, a time when biosafety protocols were modified for the care of patients with advanced respiratory disease. To improve a 15% intubation success rate on the first attempt with 90% power and an alpha of 0.05, 79 patients were included in each phase. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of our hospital (HSMLP2020/0042).

PlaceThe study was conducted in the ED at the Hospital Interzonal de Agudos San Martín de La Plata, in La Plata, Argentina. There are 315 beds for admission and in 2019, there were 34,820 emergency consultations. There are 5 resuscitation rooms in the ED and 6 beds for critical care patients, and there are emergency physicians and emergency residents with 4 residents per year. In addition, more rotating residents come from other services and stay for 2 or 3 months.

PatientsThe inclusion criteria for this study were consecutive patients of either sex with no age limit who required intubation in our ED. There were no exclusion criteria.

InterventionsThe intervention was carried out after the completion of the registry in the first phase. It consisted of four pillars: theoretical teaching, practical exercises on individual and team skills, cognitive aids, and a pre-intubation checklist. The last two pillars were presented on posters that were pasted on the walls so that they could be easily seen in the resuscitation rooms (see supplementary material in the Appendix). Ear and sternal alignment, use of the bougie during the first intubation attempt, proper traction and handling of the laryngoscope, appropriate use of the endotracheal tube and insertion of the bougie, and external manipulation of the larynx were recommended during intervention training. Mannequin models of intubations and rescue devices (laryngeal mask and cricothyrotomy) were used for the practical exercises. Strictly followed the safety protocols recommended by health authorities for practical sessions. The number of participants per session was limited to ensure social distancing, and personal protective equipment (PPE) was used. The main authors of the article conducted training sessions with theoretical activities and practical instructions. They focused on the main points to improve the FPS rate and emphasized the importance of optimizing the oxygenation and hemodynamic resuscitation of the patient before intubation when immediate airway management is not required. Cognitive aids in the resuscitation room and the use of pre-intubation checklists were introduced. Both emergency physicians, emergency residents, and rotating residents received the training. The emergency department only had a direct Macintosh laryngoscope available, which was used for all intubations.

Main interest variablesSeveral variables were included in the registry, such as the operator experience, the number of intubation attempts, intubation judgment, predictors of a difficult airway, Cormack score, assist devices, complications, blood pressure, heart rate, and pulse oximetry before and after intubation.

We define an intubation attempt as the insertion of a laryngoscope into a patient's mouth, even if the endotracheal tube does not pass. Some of the categories of the difficulty airway variable included obesity, reduced mouth opening, restricted cervical mobility, thyrohyoid distance >2 and facial trauma.

After each intubation, the operator or observer made the register in a standardized electronic form that had access to each device through a link, and, data were automatically imported into a relational database. The collected data was used to make a table with absolute and relative frequencies for the qualitative variables. Measures of central trends and dispersion were calculated for the quantitative variables. This was done in the pre-intervention phase and in the post-intervention phase.

To assess the homogeneity of the sample between the two phases, proportion estimators were calculated for the qualitative variables and median estimators for the quantitative variables. The estimators were compared with the Fisher test for the first case and with the permutation test for the second case.

The percentage of intubation was calculated at the first attempt, before and after the intervention with a 95% confidence interval. The Wilson score method was used. The percentage difference was analyzed by making the comparison between proportions and Fisher's exact test statistically significant at 0.05.

To identify the factors associated with intubation failure on the first attempt, considering possible confounding factors, a multiple logistic regression model was performed, using all the variables involved in this study. The adjusted odd ratios with their statistical significance were calculated with the coefficients estimated in this model.

The associations between complications after intubation and intubation on the first attempt were measured using the odds ratio calculation with a statistical significance of 0.05. The program R 4.4.1 was used.

ResultsStudy patientsData was collected from 287 patients. 21 were excluded because of insufficient data or duplicate data. 266 patients remained for analysis, of whom 123 belonged to the baseline period and 143 to the post-intervention period (Fig. 1).

Although the general demographic characteristics of patients were similar in both phases, there were more patients with trauma on the first phase (26% vs. 9.8%, p<0.001) and more patients with positive COVID on the second phase (50% vs. 17%, p<0.001) (Table 1). Although our hospital primarily treats adult patients 15 years of age and older, pediatric patients are occasionally admitted by their guardians in emergencies. Of the participants in our study, only one pediatric patient, a 1-year-old who required intubation for cardiac arrest, was included in the analysis.

Characteristics of patients undergoing tracheal intubation during two stages.

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=123 | N=143 | ||

| Female patients (%) | 38 (31.7) | 44 (30) | 0.236 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 53 (18) | 54 (18) | 0.655 |

| Trauma (%) | 32(26.0) | 14(9.8) | <0.001 |

| COVID+ (%)a | 22(20.7) | 71(51.7) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac arrestb (%) | 6(4.8) | 14(9.7) | 0.164 |

| Obesity (%)c | 41(33.3) | 52(36.6) | 0.699 |

| Difficult airway characteristic present (at least 1, no obesity)d | 47 (38.2) | 49 (34.3) | 0.524 |

| Comorbidities (at least 1)e | 80 (65) | 95 (66.4) | 0.897 |

| Cormack/ Lehane score | |||

| 1 | 69 (56.1) | 94 (65.7) | 0.130 |

| 2 | 36 (29.2) | 39 (27.2) | 0.785 |

| 3 | 18 (14.6) | 10 (6.9) | 0.047 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Oxygen saturation, median (IQR), % | 98 (89.0−99.0) | 95 (88.7−99.0) | 0.890 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean (IQR)f | 140(125−160) | 137 (120−153) | 0.134 |

SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range.

With a positive result for SARS-CoV-2 (PCR or flu test). No COVID swab data in 18 patients during pre-intervention and 4 post-intervention periods (In the first wave the swab criteria was more restricted).

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the intubation procedure in both phases of the study: the experience of the operator performing intubation, the drugs used (inductors and neuromuscular blockers), and the tools used to facilitate intubation (bougie and stylet).

Characteristics of the intubation procedure.

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=123 (%) | N=143 (%) | |||

| Operator who made the first attempta | Attending emergency physicians | 26 (21.1) | 15 (10.5) | 0.078 |

| Senior Resident | 24 (19.5) | 25 (17.5) | 0.873 | |

| Junior Resident | 51 (41.4) | 82 (57.3) | 0.014 | |

| Rotating Resident | 22 (17.8) | 22 (15.4) | 0.622 | |

| Sedative | Yes | 116 (94.3) | 123 (86) | 0.027 |

| Ketamine | 84 (72.4) | 95 (77.2) | 0.456 | |

| Propofol | 15 (12.9) | 3 (2.4) | 0.002 | |

| Ketamine+Propofol | 16 (13.8) | 10 (8.1) | 0.212 | |

| Etomidate | 1 (0.8) | 15 (12.2) | <0.001 | |

| Neuromuscular blockade, | Yes | 117 (95.1) | 125 (87.4) | 0.032 |

| Succinylcholine | 78 (66.6) | 63 (50.4) | 0.013 | |

| Rocuroniumb | 17 (14.5) | 50 (40) | <0.001 | |

| Other | 22 (18.8) | 12 (9.6) | 0.043 | |

| Intubation Facilitator | stylet | 54 (43.9) | 15 (10.5) | <0.001 |

| Bougie | 55 (44.7) | 115 (80.4) | <0.001 | |

| None | 14 (11.4) | 13 (9.1) | 0.548 |

The operator variable of the first attempt was operationalized into four categories: Attending emergency physicians: physicians with full training in the specialty with more than four years of service in the ED, Senior residents: third and fourth years in the ED, Junior residents: first and second years in the ED, Rotating resident: a physician with little experience in airway management who rotates from other services in ED.

In 181 patients (68.04%), data was recorded when the intubation was completed by the same operator who performed it. The remaining intubations were recorded by an observer during the procedure. No statistically significant difference was found when FPS was compared to the type of operator who recorded the data (p=0.344)

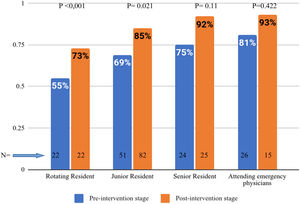

Primary resultAnalyzing the percentage change of FPS before and after the intervention, it was found that the percentage of intubation at the first attempt before the intervention was 69.9% (IC 95%: 60.89–77.68) and after the intervention was 85.3% (IC95%: 78.20–90.48), and the difference between the two was statistically significant (p=0.002). This significant increase was observed in all categories of operators (Fig. 2).

Secondary resultsMultivariate analysis (Table 3) found that less experienced professionals, Cormack-Lehane score, and lack of training (intervention) were factors associated with a higher number of intubation attempts.

Multivariate logistic regression model.

| Variables | Level | Odd Ratio | Confidence interval 95% | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Cormack-Lehane gradea | Grade 1 | Reference | |||

| Grado 2 | 1.55 | 0.94 | 2.55 | 0.08 | |

| Grado 3 | 4.13 | 2.08 | 8.69 | <0.001 | |

| Operadora | Attending emergency physicians | Reference | |||

| Rotating Resident | 6.04 | 2.69 | 14.02 | <0.001 | |

| Junior Resident | 2.98 | 1.49 | 6.12 | 0.002 | |

| Senior Resident | 2.14 | 0.97 | 4.79 | 0.061 | |

| Obesity | No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 1.14 | 0.72 | 1.83 | 0.565 | |

| Difficult airway characteristic present (no obesity) | No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 1.06 | 0.65 | 1.73 | 0.811 | |

| COVID + | No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.94 | 0.58 | 1.55 | 0.813 | |

| Indication for intubation | Medical | Reference | |||

| Trauma | 1.63 | 0.87 | 3.11 | 0.128 | |

| Interventiona | Yes | Reference | |||

| No | 2.57 | 1.61 | 4.13 | <0.001 | |

| Neuromuscular Blocker | Yes | Reference | |||

| No | 0.88 | 0.39 | 1.97 | 0.884 | |

| Inductors | Yes | Reference | |||

| No | 1.81 | 0.91 | 3.67 | 0.09 | |

No significant differences were found in the trauma and COVID subgroups in FPS.

Furthermore, any intubation performed in more than one attempt was associated with complications following intubation. Similarly, a patient who failed intubation on the first attempt had three times the odds of suffering complications than another patient who was intubated on the first attempt (odd ratio: 2.96, CI: 1.61–5.56, p<0.001).

The most common complications in this study were hypotension and hypoxia (Table 4). The latter occurred more frequently in the post-intervention period (p=0.012), whereas esophageal intubation, aspiration, and cardiac arrest were significantly reduced. Cardiac arrest after intubation, which is considered the most serious complication, occurred in eight patients (3.2%). Within this group, seven occurred during the pre-intervention phase and one during the post-intervention phase (5.9% vs. 0.7%, p=0.026). Five (62.5%) of the patients who experienced this complication presented hypotension before intubation or a shock index greater than 0.9 prior to intubation.

Intubation complications among two instances.

| Pre-interventionN=123 (%) | Post-interventionN=143 (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post intubation Hypotensiona | 21 (17.0) | 28 (19.5) | 0.636 |

| Hypoxemiab | 19 (15.4) | 41 (28.6) | 0.012 |

| Esophageal intubation | 13 (10.6) | 2 (1.4) | 0.002 |

| Aspirationc | 9 (7.3) | 1 (0.7) | 0.006 |

| cardiac arrestd | 7 (5.7) (N=117) | 1 (0.8) (N=129) | 0.026 |

| selective intubation | 4 (3.2) | 4 (2.8) | 0.99 |

| Other complicationse | 5 (4.0) | 2 (1.4) | 0.254 |

| Total complications | 78 (66.6) | 79 (61.2) | 0.300 |

| 2 or more complicationsf | 20 (16.26) | 15 (10.48) | 0.203 |

Bold formatting in the table is used to highlight statistically significant results.

Hypotension was defined as a systolic blood pressure less than 90mmHg after intubation that was not due to another cause (e.g., acute hemorrhage).

Postintubation hypoxia was defined as saturation less than 90% (or if the attempt started with saturation <90% or a decrease in saturation of >10%).

In this study, only one patient (0.3%) required surgical cricothyrotomy at the front of the neck because intubation and oxygenation were not possible.

DiscussionKey resultsIn this study, it was found that the intervention performed had a significant impact on the FPS, increasing by 15.4% in the post-intervention phase. The percentage of FPS (85.3%; IC95%: 78.20–90.48) achieved in this second phase was similar to the previously informed in a systematic review and meta-analysis.11

The improvement in FPS in this study is even more relevant when we consider three potential drawbacks. First, a high number of intubations were performed by residents who were relatively inexperienced in airway management (junior residents) in the post-intervention period compared with the baseline period. Second, in the post-intervention period, there was a higher proportion of patients who were intubated due to severe COVID -19 pneumonia, which may pose a greater challenge to airway management from a pathophysiologic perspective (if oxygen saturation is above 90% but drops rapidly, the intubator could stop the procedure and attempt to restore oxygenation, which could affect the outcome of the variable FPS.13 Finally, all intubations were performed with direct laryngoscopy, a device that has lower FPS rates compared with the use of a videolaryngoscope in ED.14–17 Although videolaryngoscopy has been shown not only to improve glottic visualization but also to reduce the number of failed attempts, it is still not available in all emergency departments. Therefore, a simple intervention similar to the one presented in our study may be considered helpful in EDs in low-to-moderate resource countries where this expensive technology is not readily available.

Study interpretationStudy data may be interpreted as supporting that the intervention performed was the key to improve the FPS percentage and thus reducing the risks associated with the procedure, other than hypoxemia. These results correlate with other similar publications. Corl et al. found a 16.2% improvement in a successful posterior intubation compared with the use of the modified Montpelier protocol. At the same time, they found a 12.6% decrease in complications.18 In a study conducted in three intensive care units, Jaber et al. also succeeded in reducing the severe complications associated with tracheal intubation by up to 13% after following an intervention protocol (intubation care bundle management).19

In a recent study conducted by Nauka et al.,20 a higher rate of successful endotracheal intubations was found during the pandemic. The authors attribute this improvement to the significant increase in the use of neuromuscular blocking agents and video laryngoscopy during the pandemic. Similarly, Leeies et al.21 found higher rates of successful endotracheal intubations when comparing pre- and post-pandemic stages. The authors concluded that the modifications made to the intubation processes in response to the COVID-19 pandemic do not appear to be associated with worse outcomes compared to pre-COVID-19 practices.

In addition to training, the introduction of cognitive tools and checklists on the walls of the resuscitation room was a significant factor in the results of this study. Although pre-intubation checklists have been shown to reduce complications such as hypoxemia, they have not been shown to reduce mortality yet. However, they can be helpful tools to optimize teamwork and effective communication. It also ensures that elements are immediately available when needed.22,23

In the post-intervention period, changes were made to the procedure and medications used to demonstrate adherence to the intervention components. The choice of medications when performing intubations must be adapted to the pathophysiologic state of the patient.24 Propofol, which tends to cause hypotension as its main side effect,25,26 was used less frequently and replaced by etomidate, which is more hemodynamically stable. Ketamine, usually recommended as a pre-intubation sedative to shock patients,24,27 was similarly administered on the first and second phases. The increased use of rocuronium in the post-intervention phase can be attributed to the fact that new drugs were added to the hospital's medical inventory during this period, as well as to the training in the use of this drug provided during the intervention phase. The low proportion of Cormack 3 in the post-intervention phase could also be interpreted as a result of the training, in which the correct laryngoscopic maneuver, adequate positioning of the patient, and manipulation of the external larynx during the procedure were particularly emphasized. The bougie, which has been associated with higher rates of FPS in emergencies,28 became part of the recommendations made during the intervention phase, and it was more frequently used in the post-intervention phase. A recent multicenter study made by Drivers et al.29 showed that the use of a bougie did not significantly increase the frequency of successful intubation on the first attempt compared with the use of a stylet endotracheal tube. Despite these results, we believe that in well-trained hands, the bougie is a critical tool for the first attempt at intubation.

Contrary to expectations, obesity was not one of the factors associated with the number of intubation attempts. In other publications, this factor was mentioned as the main difficulty with a higher failure rate.30,31 This could be due to high compliance with ramp positioning or useful intubation aids such as the bougie,32 the stylet,33 or external laryngeal manipulation.34 At least one of these strategies was used in 83 obese patients (89.24%). However, it must be considered that in our study, obesity was defined by the visual assessment of the operator.

Although the first phase of the study had a higher proportion of patients with trauma (26% vs. 9.8%, p<0.001) and this patient population is known to have lower FPS rates due to increased difficulty of intubation,11 there were no significant differences in FPS success rates compared with patients with clinical pathologies.

A higher number of intubation attempts were associated with Cormack-Lehane grade, lack of experience of the physician performing the intubation, and lack of training in multivariate analysis. Similar results were found in other studies.35–37

Regarding complications, the differences in hypoxemia between the two phases could be explained by the highest proportion of patients with severe COVID respiratory failure who required intubation in the post-intervention phase. This is also supported by the fact that pre-intubation oxygen saturation levels were different between the pre-intervention and post-intervention groups, with a median of 98% (IQR: 89.0−99.0) and 95% (IQR: 88.7−99.0), respectively.

A recently published study by Cattin et al.,38 conducted during the same period as our study, found a higher incidence of hypoxemia (43.5%) and hemodynamic instability (65%) compared with our study. We believe that the higher levels of hypoxemia may be due to the fact that all patients included in this study had a confirmed diagnosis COVID -19, whereas the higher proportion of hemodynamic instability may be due to the fact that the authors reported the use of midazolam as the induction agent of choice in most intubations and in 43.63% of cases in combination with propofol, both well known hypotensive drugs. A recent large multicenter study by Vincenzo et al. reported an incidence of hemodynamic instability of 42.6%, which was also higher than ours but with a lower incidence of hypoxemia (9.3%).

It is important to highlight that in the post-intervention period, a higher number of intubations were performed in a shorter time frame. This increase may be attributed to the fact that more patients with severe pneumonia due to COVID -19 were admitted during this period. As a result, the daily intubation rate increased by 87.5% compared with the preintervention period, with the average number increasing from 0.8 intubations per day (123 intubations in 153 days) to 1.5 intubations per day (143 in 92 days) after the intervention.

Interestingly, the lower incidence of cardiac arrest after intubation in the post-intervention phase (0.6%) was comparable to the study by Park & col.11

LimitationsOur study has several limitations. First, since it is a quasi-experimental one from a single institution, we can not draw definitive conclusions to prove causality. Second, it is possible that the observed effects were enhanced by the acquisition of more experience, as operators performed a greater number of intubations during the study, independent of the intervention itself. Third, the number of attempts was recorded but not the time spent on them. Fourth, the low percentage of FPS on the first phase of the study may have been influenced by changes in intubation care and operator fear of infection during the procedure.

ConclusionIn our study, a low-cost and simple educational intervention was significantly associated with an improvement in FPS and achieved the same rate of FPS as in high-income countries. Considering our results, it would be important to continue working on this multi-approach model to create a useful and replicable tool in ED to improve intubation quality standards without the need for costly new devices.

Statements and declarationsThe authors do not have any conflict of interest to declare. This research study was not financed.

Authors’ contributionsGJM: study concept and design, manuscript writing, coordinated the input of all authors, supervised the study and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. GA: data analysis and interpretation, revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and statistical expertise. LNC: co-designed the study, data collection and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. SB: co-designed the study, data collection and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. SM, AR and MV: data collection and revised the manuscript. RR and GM: Critical manuscript review, and study supervision. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Cecilia Serpa, Cecilia Loudet, Carlos Leiva, Bruno Ghissi, Mercedes Soler, Gamonal Sumiko, Perazzo Marcos, Satrustegui Maria Belen, Ampuero Ariana, Bardon Sabrina, Martinez Esteban, Vitale Franco and the rest health staff of the emergency department of San Martín Hospital in La Plata City.