Editado por: Alberto García-Salido - Cuidados Intensivos Pediátricos, Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús, Madrid

Última actualización: Mayo 2024

Más datosIn January 2020, a new coronavirus known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was described in Wuhan, China. The virus, which produces coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has been declared a global health emergency and pandemic by the World Health Organization. Spain is one of the more severely affected countries.1

The immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection appears to be a critical factor in the development and prognosis of COVID-19 patients.2 In children, severe forms of the disease like the pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 appears to be related with some immune dysregulation.3 So, increase knowledge about the innate cellular immune response to SARS-CoV-2 is of great interest. To this, the study by flow cytometry (FC) may provide critical data and further understanding of this novel disease.3

In this paper, we study three molecules which are part of the innate cellular response to infection: CD64, CD18 and CD11a. The CD64 is a type I high-affinity receptor for the Fc fraction of the immunoglobulin G. It is located on monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and neutrophils. The CD64 density on the cell surface is related to the stimulation received by inflammatory cytokines4. The CD18, also known as integrin beta-2, participates in leukocyte adhesion and signaling. The CD11a associates with CD18 to form the lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1, or LFA-1. This LFA-1 on leukocytes plays a central role in leukocyte cell-cell interactions and lymphocyte stimulation.

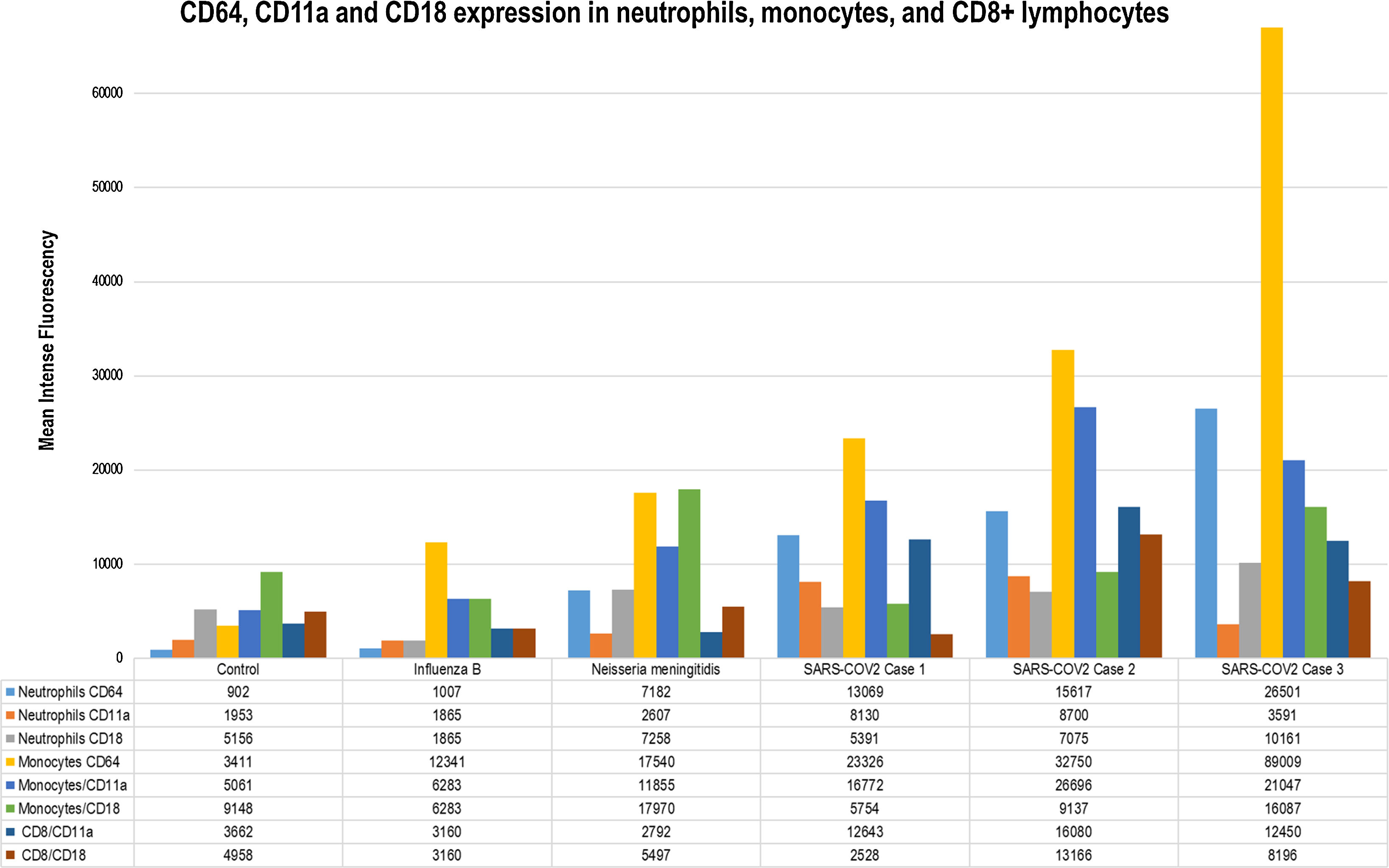

We study in this report three children with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Also, we compare them with a healthy control, a case of severe influenza infection and a case of Neisseria meningitidis sepsis. All cases included had SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) on nasopharyngeal swab samples. The cases trajectories, complementary tests, and therapy approaches are summarized in Table 1. The children were studied after informed consent was obtained. One 0.5ml sample of peripheral blood was extracted on admission to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). The samples obtained were collected in sterile EDTA at room temperature or refrigerated at 4°C, after which they were used for CD45+ cell-marker studies and analyzed by FC within 24h. Cell surface expression of CD64, CD18, and CD11a was measured by BD FACS Canto II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, New York, USA). CD64 (clone 10.1), CD18 (clone CBR LFA-1/2), and CD11a (clone HI111) monoclonal antibodies were obtained from Biolegend® (San Diego, CA, USA). Expressions were measured in monocytes, neutrophils, and lymphocytes. Cell viability was confirmed by 7-AAD staining. At least 10,000 events were recorded for each sample. Flow-cytometric settings and samples were prepared according to manufacturer instructions. Neutrophils, monocytes and lymphocytes were identified on a dot-plot and gated (Fig. 1). The intensity of CD64, CD18, and CD11a surface expression was measured as mean fluorescence intensity in arbitrary units (MFI, Fig. 1B).5 The FC was performed on PICU admission in all cases. All patients received methylprednisolone prior to FC.

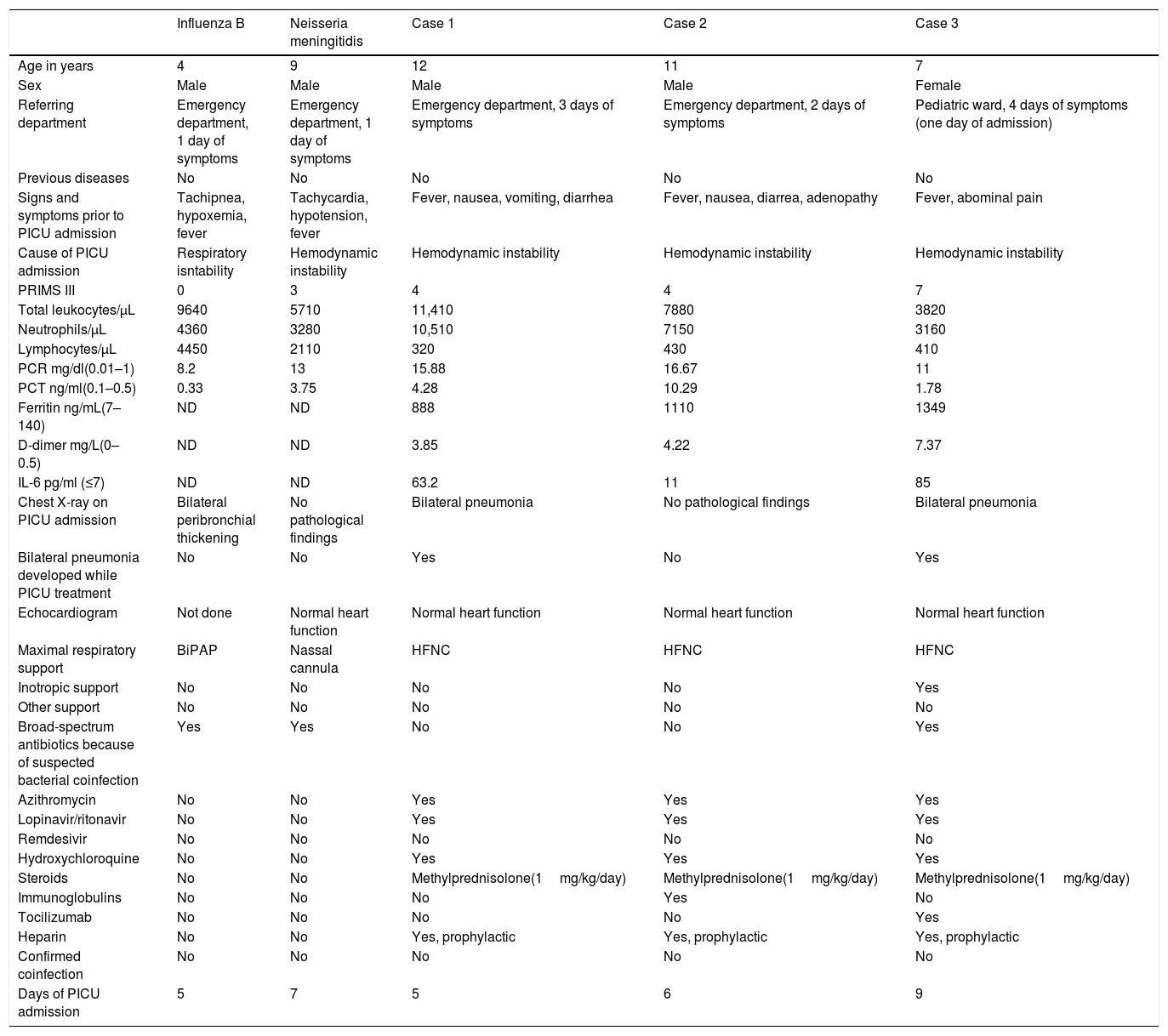

Epidemiologic characteristics, clinical features, radiologic findings, and management of children admitted for pediatric critical care due to Influenza B, Neisseria meningitidis and SARS-CoV-2 infection.

| Influenza B | Neisseria meningitidis | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 4 | 9 | 12 | 11 | 7 |

| Sex | Male | Male | Male | Male | Female |

| Referring department | Emergency department, 1 day of symptoms | Emergency department, 1 day of symptoms | Emergency department, 3 days of symptoms | Emergency department, 2 days of symptoms | Pediatric ward, 4 days of symptoms (one day of admission) |

| Previous diseases | No | No | No | No | No |

| Signs and symptoms prior to PICU admission | Tachipnea, hypoxemia, fever | Tachycardia, hypotension, fever | Fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea | Fever, nausea, diarrea, adenopathy | Fever, abominal pain |

| Cause of PICU admission | Respiratory isntability | Hemodynamic instability | Hemodynamic instability | Hemodynamic instability | Hemodynamic instability |

| PRIMS III | 0 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 7 |

| Total leukocytes/μL | 9640 | 5710 | 11,410 | 7880 | 3820 |

| Neutrophils/μL | 4360 | 3280 | 10,510 | 7150 | 3160 |

| Lymphocytes/μL | 4450 | 2110 | 320 | 430 | 410 |

| PCR mg/dl(0.01–1) | 8.2 | 13 | 15.88 | 16.67 | 11 |

| PCT ng/ml(0.1–0.5) | 0.33 | 3.75 | 4.28 | 10.29 | 1.78 |

| Ferritin ng/mL(7–140) | ND | ND | 888 | 1110 | 1349 |

| D-dimer mg/L(0–0.5) | ND | ND | 3.85 | 4.22 | 7.37 |

| IL-6 pg/ml (≤7) | ND | ND | 63.2 | 11 | 85 |

| Chest X-ray on PICU admission | Bilateral peribronchial thickening | No pathological findings | Bilateral pneumonia | No pathological findings | Bilateral pneumonia |

| Bilateral pneumonia developed while PICU treatment | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Echocardiogram | Not done | Normal heart function | Normal heart function | Normal heart function | Normal heart function |

| Maximal respiratory support | BiPAP | Nassal cannula | HFNC | HFNC | HFNC |

| Inotropic support | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Other support | No | No | No | No | No |

| Broad-spectrum antibiotics because of suspected bacterial coinfection | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Azithromycin | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Remdesivir | No | No | No | No | No |

| Hydroxychloroquine | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Steroids | No | No | Methylprednisolone(1mg/kg/day) | Methylprednisolone(1mg/kg/day) | Methylprednisolone(1mg/kg/day) |

| Immunoglobulins | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Tocilizumab | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Heparin | No | No | Yes, prophylactic | Yes, prophylactic | Yes, prophylactic |

| Confirmed coinfection | No | No | No | No | No |

| Days of PICU admission | 5 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 9 |

PICU: pediatric intensive care unit; HFNC: high flow nasal cannula; BiPAP: Bilevel Positive Airway Pressure; pSOFA: Pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; PRISM III: Pediatric Risk of Mortality Score; ND: not done.

(A) CD64 staining on granulocytes, monocytes, and lymphocytes in periphal blood samples obtained on pediatric critical care unit (PICU) admission. From left to right, we can observe the CD64 expression. CD64 is expressed on monocytes and neutrophils but not lymphocytes (internal negative control). The positive CD64 region is located to the right of the dotted line. As can be seen, neutrophils gated in the control case are crossed by this line. (B) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values for CD64, CD11a, and CD18 are given for each case in the form of a bar chart. As can be seen in all cases, CD64 and CD11a expression is higher in SARS-CoV-2 cases. This observation is clear for CD64. The CD11a expression on CD8+ lymphocytes is also upregulated compared to previous data.

As results, we provide the description of CD64, CD18, and CD11a expression on neutrophils, monocytes and lymphocytes in children with severe SARS-CoV-2 disease. This expression appears to be higher compared to other infections and may point to an exacerbated cellular innate response in these children.3–6

The cytopathic effects of SARS-CoV-2 combined with the host immune response may play a major role in disease severity. A dysregulated immune response may result in inflammation and clinical worsening in patients with COVID-19. Elevated CD64 expression have been previously described in infectious and noninfectious diseases.7 Our group carried out CD64 expression studies in acute bronchiolitis and severe viral and bacterial infections.5 As can be seen in Fig. 1 children with SARS-CoV-2 show levels of CD64 expression that are higher than in previous published reports of bacterial or viral infections or autoinflammatory diseases.5 Regarding the CD11a and CD18 complex or LFA-1, it is known that plays a key role in migration. Through these, leukocytes are mobilized from the bloodstream into tissues. One of the main findings in COVID-19 patients is the presence of lymphopenia.8 It can be seen in our cases. This may be linked to the migration of CD8+ lymphocytes to the infected tissues. As seen in Fig. 1, the CD11a upregulation in CD8+ is clear and could be linked to this process. The LFA-1 is also involved in the process of cytotoxic T cell-mediated killing as well as antibody-mediated killing by granulocytes and monocytes.9 The upregulation of both leukocyte populations is also observed in our cases (Fig. 1).

Immunomodulatory treatment seems to have a great role in COVID19. Their use should be based on a risk-benefit analysis. In SARS-CoV-2 infections the cytokine storm theory coupled with analytical data are used to justify these approaches.2,10 Our FC results introduce a new approach to analyzing the immune response to this new virus. We confirm the activation of the innate cellular response. Besides we observed that is different and maybe higher than in other infections. The description of this immune status using FC could individualize the diagnosis and optimize the therapies applied.

In summary, we describe the immunophenotype of three children with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. We observed significant upregulation of CD64, CD18, and CD11a expression on leukocytes. Compare to previous papers and to other types of infection it appears to be higher. This could inform about immune dysregulation triggered by SARS-CoV-2. The use of FC may lead to a better understanding of this response and optimize the therapies applies. Prospective studies with a higher number of cases should be conducted to confirm this observation.

Financial disclosureThe authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.