The prevalence of severe poisoning with sedatives or hypnotics has been increasing dramatically over the last years.1 In this setting, barbiturates remain one of the most common classes of drugs associated with fatal poisoning. The current report aims at illustrating the usefulness of renal replacement therapy with intermittent hemodialysis in the acute care of massive phenobarbital poisoning.

A 56-year old woman was addressed to the intensive care unit (ICU) for a massive phenobarbital poisoning (assumed ingested dose: 5.5g). The estimated maximum delay between phenobarbital ingestion and ICU admission was 6hours. The patient presented with hypotension (77/44mmHg), hypothermia (33°C) and altered mental status (Glasgow Coma Scale: 3) requiring endotracheal intubation, fluid loading with 1000mL of saline and noradrenalin infusion up to 0.33μg/kg/min before ICU admission. Her neurological examination revealed bilateral mydriasis with no pupillary response, together with the disappearance of other brainstem reflexes. A trans-thoracic echocardiography showed preserved left ventricle ejection fraction and cardiac output consistent with a vasoplegic shock. In spite of the profound coma and respiratory depression, there was no evidence for aspiration. The diagnosis of massive phenobarbital poisoning was confirmed by high barbiturate plasma levels measured upon admission (273mg/L).

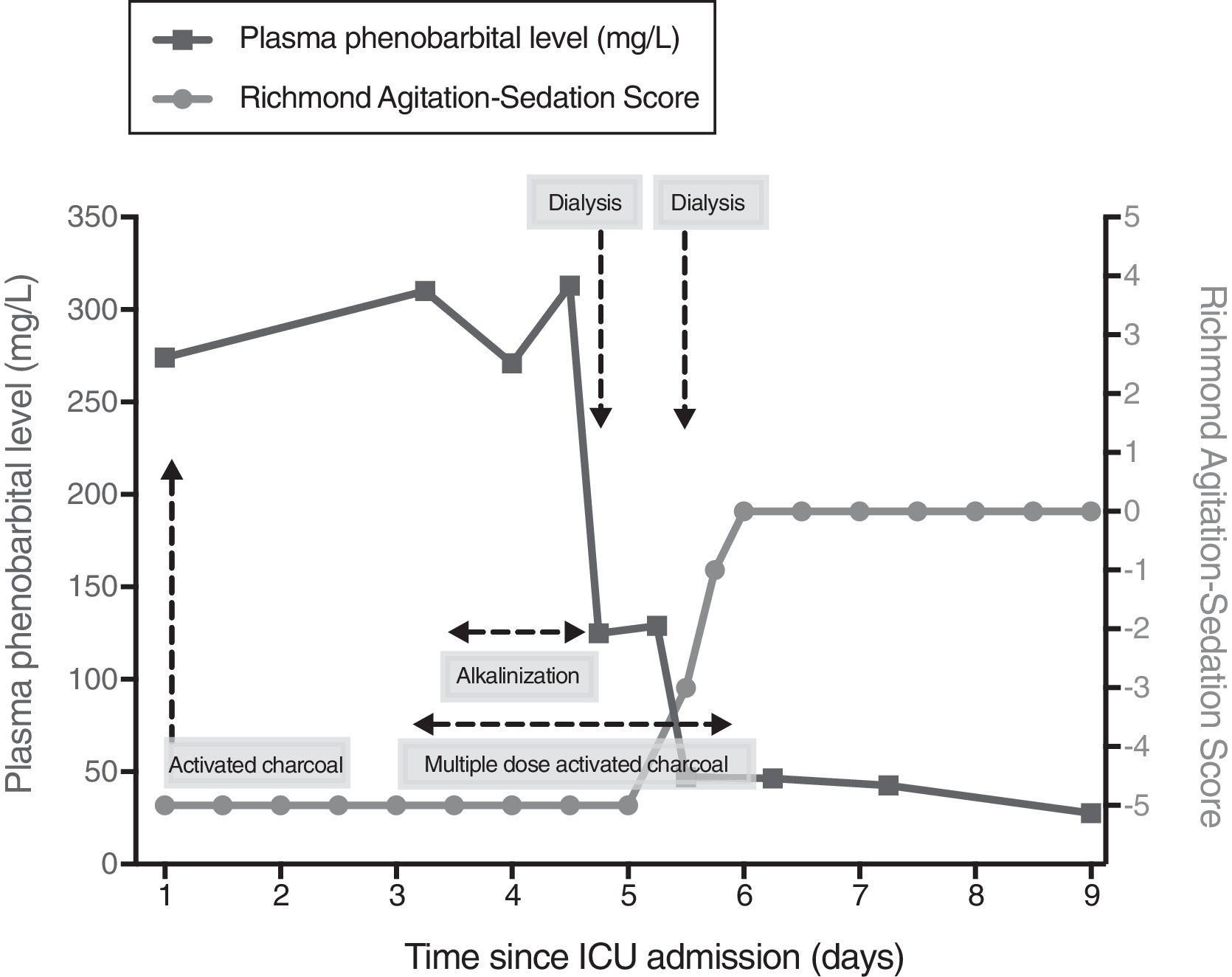

Initial management of barbiturate poisoning included supportive care of organ failures (i.e., mechanical ventilation and noradrenalin infusion), the administration of activated charcoal (a single 1g/kg dose) so that to limit the enterohepatic recirculation of barbiturates, together with urinary alkalinization in an attempt to increase their urinary excretion. On day-1, hemodynamic improvement allowed for noradrenalin discontinuation. Yet, the neurological examination was no significantly improved (GCS: 3), except for a spontaneous breathing activity under mechanical ventilation. Multiple-dose activated charcoal (MDAC) was introduced on day-2, with no significant decrease in plasma phenobarbital levels or neurological improvement (Fig. 1). On day-4, because the patient was still deeply comatose, renal replacement therapy (RRT) initiation was decided. Intermittent dialysis was performed using an Artis Physio™ dialysis system (Gambro AB, Meyzieu, France) with a Sureflux™-19E dialyzer (Nipro Europe, Saint Beauzire, France), achieving an estimated average creatinine clearance of 188mL/min. A 4-hour session allowed for dramatically reducing plasma phenobarbital levels from 313 to 125mg/L. The second dialysis session, performed on day-5, further reduced plasma levels from 129 to 47mg/L (Fig. 1). The patient awoke twenty-four hours after RRT initiation, as illustrated by an increase in the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale from −5 (patient unarousable) to 0 (patient alert and calm) (Fig. 1). The clinical course was eventually favorable, allowing for the patient to be successfully extubated on day-7 and discharged to a psychiatric unit on day-10.

We herein report a case of massive phenobarbital poisoning with a favorable course under intermittent hemodialysis. Medical interventions to enhance phenobarbital elimination (activated charcoal and urinary alkalinization) had failed to improve the neurological status of our patient. Also, this strategy did not significantly alter phenobarbital plasma levels. In a previous study, the administration of repeated doses of activated charcoal enhanced the elimination of barbiturates but had no clear effect on clinical outcome.2 Furthermore, activated charcoal could hypothetically increase the risk of gastric impaction. This may partially explain the variation in serum concentrations during the initial course (between day-1 and day-4), as phenobarbital is a long-acting barbiturate. Regarding urinary alkalinization, there is to date no clinical evidence of a clinical benefit in barbiturate poisoning, despite its pharmacokinetic rationale.3

In the current case, RRT with intermittent hemodialysis dramatically improved the clearance of phenobarbital and, hence, neurological status improved concomitantly. Two 4-hour sessions were sufficient to achieve a dramatic reduction in phenobarbital levels. Hemodialysis was discontinued after neurological status improved, rather than targeting a specific concentration. All barbiturates are inducers of the hepatic cytochrome P450 and hepatic metabolism is the main component of their endogenous clearance. Barbiturates are thus classified according to their pharmacokinetic properties. Long-acting barbiturates (such as phenobarbital) have a smaller volume of distribution, which tends to limit post-dialysis rebound, and are less protein-bound and lipid soluble than short-acting barbiturates. Importantly, up to 20–25% of phenobarbital can be excreted as an active drug in urine. During dialysis, phenobarbital clearance has been shown to vary from 150 to 200mL/min.4 For all these reasons, long-acting barbiturates are theoretically dialyzable. A few case studies have reported the effectiveness of both hemoperfusion5,6 and hemodialysis7,8 to enhance the clearance of barbiturates. Yet, these two techniques have not been evaluated and compared in randomized control trials. Hemoperfusion is not widely available and requires a specific training. As compared to hemoperfusion, hemodialysis has been shown to be associated with a lower risk of thrombocytopenia or hypocalcemia and seems less costly.9 The 2015 recommendations of the EXTRIP Workgroup suggest using intermittent hemodialysis to treat long-acting barbiturate poisoning in case of prolonged coma, shock (after initial fluid resuscitation), or persistence of toxicity despite MDAC.10

This case provides further support for the early initiation of renal replacement therapy in patients admitted for severe long-acting barbiturates poisoning, especially in those with prolonged coma and/or persistence of toxicity despite multiple-dose activated charcoal.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.