Withdrawal of mechanical ventilation (MV) is a major challenge for intensivists, being a daily spontaneous breathing trial (SBT) the best approach to check the patient's ability to breathe.1 We demonstrated that a less demanding SBT has a higher successful extubation rate than a more demanding SBT.2 Reintubation rate remains around 10-25% and is related to worse prognosis and mortality.3

Higher risk of reintubation is classically associated with obesity (BMI>30), MV>7 days, COPD, APACHE II>12 points, age>65 yo, and cardiac failure.4 We hypothesized that clinical variables during SBT could be helpful to predict the risk of reintubation.

This is a post-hoc analysis of a multicenter clinical trial that compared two opposite strategies of spontaneous breathing trials (SBT), 30-min PSV and 2-h T-piece.2 In the present analysis after excluding missing data, 443 patients performed a 2-hour T-piece-SBT and 507 patients a 30-minute PSV–SBT. Variables identified by multivariable logistic regression as associated with reintubation were respiratory rate (RR)>25bpm at the end of SBT (OR 1.99 (1.13–3.49)) and length of MV>4 days (OR 1.86 (1.20–2.87)). The coefficients of these variables were used by logit methodology to calculate a reintubation score. Logit model is used to model the probability of a certain event existing such as present/abscent. Each variable being detected would be assigned a probability between 0 and 1, with a sum of one. Based on the OR or Beta resulted from the logistic regression, the risk of failure was calculated for each patient. According to this score, the patients were classified as low-risk for reintubation (<10%), medium-risk (10–20%), and high-risk for reintubation (>20%). We compared this model with the one with classical variables.

Categorical variables are presented as absolute and relative frequencies. Continuous variables are summarized as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for non-normal distribution. Statistics were used as usual for normal and non-normal variables.

Both SBT techniques were used in similar proportion in the three risk groups (p=0.402). The age, gender and incidence of previous pathologies were similar between groups. In the whole sample, 69% of patients were medical patients. In the Low-risk group, 25% were medical respiratory and 42% medical non-respiratory. In the Medium-risk group, the proportion of respiratory (36%) and non-respiratory (35%) were similar. In the High-risk group, the respiratory patients were more frequent than non-respiratory (47% vs. 24%) (p<0.001). APACHE-II score at ICU admission was higher in Medium and High-risk group than in Low-risk (14 vs 17, p<0.001). The incidence of COPD was similar in all groups (10% in Low and Medium Risk; 17% in High Risk, p=0.268). Despite not being significative, the Body Mass Index, tended to be higher in the High Risk group (28.1) than in Low and Medium Risk group (25.9 and 26.5) (p=0.055). The duration of MV before SBT was longer in High-risk (7.5 days) and Medium-risk (7 days) than in Low-risk (2 days) (p<0.001). The RR (at the beginning and at end of the SBT) was higher in the High-risk group (24 and 28) than in Medium-risk (18 and 19) and Low-risk groups (15 and 16) (p<0.001) (Table 1).

Baseline characteristics and outcomes of each group of Risk.

| Total (n=950) | Low Risk (n=618) | Medium Risk (n=197) | High Risk (n=135) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 64 (52–74) | 65 (52–75) | 63 (53–73) | 58 (45–75) | 0.554 |

| Female gender (%) | 357 (38%) | 169 (41%) | 161 (34%) | 27 (41%) | 0.137 |

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2 | 26.3 (24.2–29.3) | 25.9 (23.9–28.7) | 26.5 (24.2–29.6) | 28.1 (25.4–31.2) | 0.055 |

| Comorbidities (%) | |||||

| Diabetes | 216 (23%) | 100 (25%) | 103 (22%) | 13 (20%) | 0.623 |

| COPD | 180 (19%) | 80 (19%) | 89 (19%) | 11 (17%) | 0.884 |

| Hepatopathy | 102 (11%) | 42 (10%) | 49 (10%) | 11 (17%) | 0.268 |

| Chronic renal disease | 123 (13%) | 58 (14%) | 60 (12%) | 5 (8%) | 0.357 |

| Reason for ICU admission (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Medical respiratory | 304 (32%) | 103 (25%) | 170 (36%) | 31 (47%) | |

| Medical no respiratory | 356 (37%) | 174 (42%) | 166 (35%) | 16 (24%) | |

| Emergent surgery | 173 (18%) | 73 (17%) | 89 (19%) | 11 (17%) | |

| Planned surgery | 56 (6%) | 34 (8%) | 16 (3%) | 6 (9%) | |

| Trauma | 61 (6%) | 32 (8%) | 27 (6%) | 2 (3%) | |

| APACHE II, points | 16 (11–22) | 14 (10–20) | 17 (12–23) | 17 (11–23) | <0.001 |

| Length of VM, days | 4 (2–8) | 2 (1–2) | 7 (5–11) | 7.5 (5–11) | <0.001 |

| Starting-SBT respiratory rate | 17 (13–20) | 15 (12–28) | 18 (14–20) | 24 (20–26) | <0.001 |

| End-SBT respiratory rate | 18 (14–22) | 16 (13–19) | 19 (15–22) | 28 (26–30) | <0.001 |

| Prophylactic HFNC | 152 (16%) | 54 (13%) | 86 (18%) | 12 (18%) | 0.081 |

| Prophylactic NIV | 81 (8%) | 27 (6%) | 44 (9%) | 10 (15%) | 0.041 |

| Reintubation within 72 h | 108 (11.4%) | 31 (7.5%) | 61 (13%) | 16 (24.2%) | <0.001 |

| ICU length of stay, days | 9 (5–16) | 5 (3–8) | 13 (9–20) | 13 (10–22) | <0.001 |

| Hospital length of stay, days | 24 (15–39) | 16 (10–28) | 29 (19–45) | 32.5 (22–52) | <0.001 |

| ICU mortality | 47 (4.9%) | 19 (4.6%) | 27 (5.8%) | 1 (1.5%) | 0.293 |

| Hospital mortality | 110 (11.6%) | 46 (11.1%) | 60 (12.8%) | 4 (6.1%) | 0.249 |

Reintubation was needed in 31 of 416 (7.5%) patients classified as “Low-risk”, in 61 of 468 (13%) patients classified as “Medium-risk”, and in 16 of 66 (24.2%) patients classified as “High-risk” (Fig. 1). The ICU length of stay was longer in High-risk and Medium-risk patients (13 days in both) than in Low-risk patients (5 days) (p<0.001). The hospital length of stay was also longer in High-risk (32.5 days) than in Medium-risk (29 days) and Low-risk group (16 days) (p<0.001).

Despite the differences in APACHE II and reintubation rate, the ICU mortality (Low-risk 4.6%, Medium-risk 5.8%, High-risk 1.5%, p=0.293) and the hospital mortality (Low-risk 11.1%, Medium-risk 12.8%, High-risk 6.1%, p=0.249) were not different between groups.

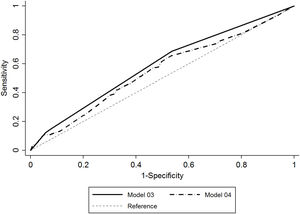

The under-ROC area of the new model was significantly better than the model with the classical variables (0.60 (0.55–0.66) vs. 0.53 (0.47–0.59) (p=0.045)), but needs better accuracy for clinical decision making (Fig. 1).

Our study is limited by the lack of a validation sample, needing additional studies for confirmation, but the multicenter approach improves the extrapolation to a wide variety of ICUs. The score is robust enough to be unaffected by the SBT technique. However, the results should be interpreted with caution because it is a post-hoc analysis of a Clinical Trial which the main objective was not stratify the patients in risk of reintubation. Far from being a good AUC, our variables showed better results than the classical ones.

The lack of difference in mortality between the groups was an unexpected result that could be due to the small sample of patients in the HR group.

We conclude that our study offers a new score for reintubation risk that is slightly better than the clinical classification used until now. It can be useful to identify which patients could benefit from more intensive prophylactic treatment or be aware of signs of alarm for failure like inability to clean secretions or cardiac failure.5