A press release in 2015 from one of the most important newspapers in the world, the Wall Street Journal,1 commented on the Risky States project of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, which allowed real-time risk estimation in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU), and on the Project Emerge of Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, which evaluates the use of complication preventive measures. The press release, addressed to society–our patients–acknowledged a change in paradigm in Medicine, with data being consolidated as the backbone of medical care and research. Specifically, the data contained in the patient case history are a formidable source of information not only for summarizing what has happened but also for identifying patients at risk (even outside the walls of the ICU) and modulating the future: helping professionals to make decisions, and contributing to focus accumulated knowledge, experience and all our talent on the care of our patients. In effect, as underscored by recent articles published in Medicina Intensiva.2–4 and in JAMA,5,6 the physician attending the patient and who possesses the knowledge and quality and cost information (through specific tools) is the individual that will exert an influence upon the necessary transition from a healthcare model based on volume to a model based on value. Only in this way can we guarantee efficient, highly qualified and patient-centered work with improved outcomes.

Information technology clearly offers an excellent opportunity for improving medical care. Our Society, through the five High Interest Recommendations,7 points to Clinical Information Systems (CIS) as a tool for incrementing quality and safety. The SEMICYUC likewise has established definitions of the technical and functional standards of the CIS.8

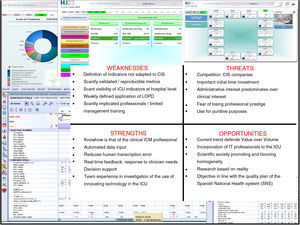

In addition to affording a database, information technology, through the CIS, makes it possible to measure what we do, analyze process adherence to scientific evidence, improve professional performance, and evaluate the impact of improvement strategies. In this regard, following a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) strategic analysis, our group has developed a platform allowing the inclusion, calculation (based on defined metrics) and analysis of the data automatically derived from the CIS (Fig. 1). It would not be possible to obtain this information through manual data entry by the Intensive Care professionals.

Data extraction from the CIS, with processing and analysis using a Business Discovery application, allows the development of an operative, automated and quasi-real time management tool (Intellectual Property: i_DEPOT No. 102487). The tool includes: service map (making it possible to graphically know the life support techniques in patients admitted on the day of consultation, and the work loads for the medical and nursing professionals); minimum Intensive Care database set (MICD-ICU); drug product consumption and expenditure; and quality indicators. In addition, it allows ad hoc consultations, with ongoing improvement objectives referred to care quality and management. LOPD: Data Protection Act; ICM: Intensive Care Medicine; CIS: clinical information systems; SNS: Spanish National Health system; IT: information technology; ICU: Intensive Care Unit.

Indicators,9 as the best tools for measuring quality, are strongly conditioned by the time required and the complexity involved in collecting the information needed to calculate them. Effort should be guided in search of indicators that are measurable, reliable and precise (reproducible), drawn from the data contained in the CIS.10 This would favor the homogenization of definitions and reduce time consumption on the part of the professionals. However, automatic calculation, seeking objectiveness, is not possible without their contribution, since medical criterion is sometimes needed in order to assess consistency with concrete definitions. This point has generated debate for example in calculating events related to mechanical ventilation.11 In any case, redefinition of an important group of indicators is probably required, establishing definitions that are consensus-based, precise and adapted to the information contained in the CIS, where possible–avoiding the duplication of efforts and the development of parallel software applications. Prior evidence has been obtained of the accuracy and correlation of the results referred to manually and automatically analyzed indicators.12

The information of the CIS will also allow a new approach to critical patient safety. Up until now, we were able to face foreseeable events by using checklists, for example.13 However, analysis of the variables contained in the CIS could offer an approach to predictive models and identify associations between variables that previously would have gone unnoticed. Based on new forms of analysis, we are able not only to avoid errors but also to monitor them and analyze their predisposing factors–including even data from other sources (position sensors referred to patients and professionals, for example).

We assume that the intensivist must define the objectives, and that technical execution is the work of software engineers–this resulting in new relationships within our specialty.14 We must be ready for other novelties such as for example the availability of professionals trained in managing the new information generated. Ghassemi speaks of a new Learning Healthcare System.15 Although traditional clinical research has been based on randomized clinical studies, there are numerous and varied databases, ranging from case histories to registries, benchmarking platforms and administrative data, among others.16 It all depends on the question we ask. What until now was years of data input, with important effort on the part of the clinician, can now be replaced or complemented by the data of the CIS. However, this great body of information cannot be addressed by means of the usual statistical models, and obliges us to speak of big data and predictive models.

Important advances have clearly been made in data acquisition, integration and storage capacity, though we also must incorporate other developments in information technology, biomedical engineering, signal processing (curves, images) and algorithms for the diagnosis of events, that can only be compiled on a computerized basis.17

In order to prevent things from becoming mere isolated events or anecdotes in the newspapers, critical care professionals must participate in the configuration of the CIS, in accordance with the care processes, with commitment to the checking of safety and quality data, and investigation of their true usefulness, reliability and correlation to the classical sources. All this will require adequate management of the change, overcoming resistances among professionals, and addressing the ethical and legal issues jointly with the administration–such steps already having been taken by the AQuAS in Catalonia, for example.18

Conflicts of interestMB and RM state that they have no conflicts of interest. LB is the inventor of a United States patent held by the Corporació Sanitaria Parc Taulí, Spain: “Method and system for managing related patient parameters provided by a monitoring device”, US Patent No. 12/538,940. LB holds shares in BetterCare S.L., a start-up of the Corporació Sanitària Parc Taulí, Spain.

Please cite this article as: Bodí M, Blanch Ll, Maspons R. Los sistemas de información clínica: una oportunidad para medir valor, investigar e innovar a partir del mundo real. Med Intensiva. 2017;41:316–318.