Acute respiratory failure which under pneumoprotective measures persistently maintains PaO2/FiO2 < 100 or a plateau P > 30 cmH2O can be classified as refractory hypoxemia. The different therapeutic strategies under such circumstances include the combination of pressure-controlled ventilation and the inverted inspiration-exhalation ratio (inverted I:E): airway pressure release ventilation (APRV).1

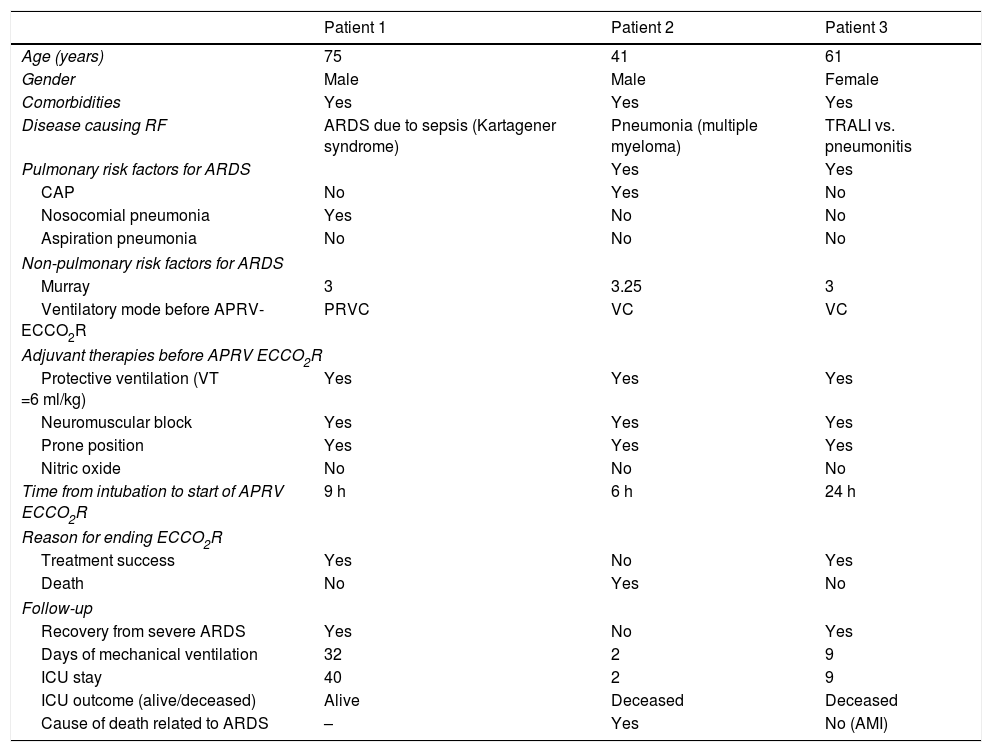

We present a series of three cases of refractory hypoxemia in which APRV was applied in combination with a low-flow CO2 removal device with renal replacement therapy (ECCO2R-RRT). Table 1 details the clinical-epidemiological and evolutive characteristics of the three cases.

Clinical, epidemiological and evolutive parameters of the patients.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 75 | 41 | 61 |

| Gender | Male | Male | Female |

| Comorbidities | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Disease causing RF | ARDS due to sepsis (Kartagener syndrome) | Pneumonia (multiple myeloma) | TRALI vs. pneumonitis |

| Pulmonary risk factors for ARDS | Yes | Yes | |

| CAP | No | Yes | No |

| Nosocomial pneumonia | Yes | No | No |

| Aspiration pneumonia | No | No | No |

| Non-pulmonary risk factors for ARDS | |||

| Murray | 3 | 3.25 | 3 |

| Ventilatory mode before APRV-ECCO2R | PRVC | VC | VC |

| Adjuvant therapies before APRV ECCO2R | |||

| Protective ventilation (VT =6 ml/kg) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Neuromuscular block | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Prone position | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Nitric oxide | No | No | No |

| Time from intubation to start of APRV ECCO2R | 9 h | 6 h | 24 h |

| Reason for ending ECCO2R | |||

| Treatment success | Yes | No | Yes |

| Death | No | Yes | No |

| Follow-up | |||

| Recovery from severe ARDS | Yes | No | Yes |

| Days of mechanical ventilation | 32 | 2 | 9 |

| ICU stay | 40 | 2 | 9 |

| ICU outcome (alive/deceased) | Alive | Deceased | Deceased |

| Cause of death related to ARDS | – | Yes | No (AMI) |

APRV: airway pressure release ventilation; ECCO2R: extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal; AMI: acute myocardial infarction; RF: respiratory failure; CAP: community-acquired pneumonia; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; VC: volume control; PRVC: pressure-regulated volume control.

The first case in which both therapies were combined corresponded to a 75-year-old male admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) due to sepsis of respiratory origin. The patient developed severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) secondary to nosocomial pneumonia, and mechanical ventilation was started. Anuric renal failure was diagnosed and renal replacement therapy (RRT) was decided. After 9 h of protective ventilation, and due to the persistence of refractory hypoxemia, we introduced APRV followed by ECCO2R-RRT. The patient was discharged after 40 days in the ICU.

The second case corresponded to a patient admitted to the ICU with a diagnosis of possibly progressing multiple myeloma with established renal failure and severe respiratory failure secondary to community-acquired pneumonia. Upon admission to intensive care, mechanical ventilation was started and pneumoprotective measures were adopted, together with RRT. In view of the failure of these measures and the rapid progression of the clinical condition, combined therapy with APRV and ECCO2R-RRT was started. Despite initial improvement, however, the patient died of hypoxia in the following 12 h.

The third case corresponded to an episode of respiratory failure of uncertain origin in a woman who had been treated with cetuximab due to a tumor of the floor of the mouth. She had undergone blood product transfusion 24 h before developing rapidly evolving severe ARDS. The patient was admitted to the ICU due to respiratory failure that progressed with multiorgan failure and anuric acute respiratory failure. In this case, ECCO2R was started 24 h before switching the ventilatory mode to APRV. On the eighth day of mechanical ventilation, and in view of resolution of the lung disease, mechanical ventilation weaning maneuvers were started. The patient died 24 h later due to acute myocardial infarction.

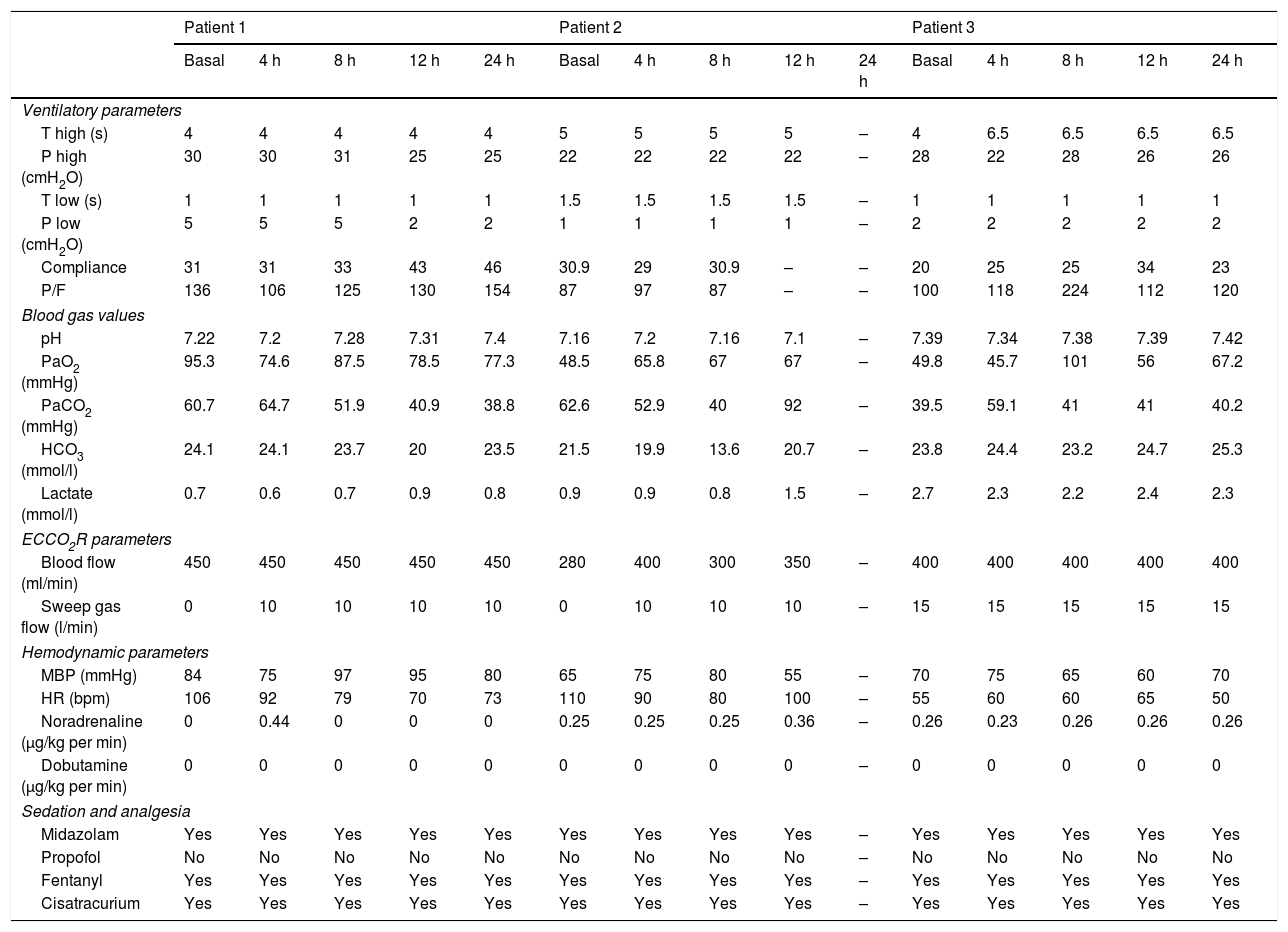

Table 2 details the modifications of the ventilatory parameters, ECCO2R and the blood gas and hemodynamic values following the start of combined APRV and ECCO2R-RRT.

Evolution of the ventilatory, blood gas, ECCO2R, hemodynamic and sedoanalgesia parameters during the first 24 hours.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal | 4 h | 8 h | 12 h | 24 h | Basal | 4 h | 8 h | 12 h | 24 h | Basal | 4 h | 8 h | 12 h | 24 h | |

| Ventilatory parameters | |||||||||||||||

| T high (s) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | – | 4 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.5 |

| P high (cmH2O) | 30 | 30 | 31 | 25 | 25 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | – | 28 | 22 | 28 | 26 | 26 |

| T low (s) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| P low (cmH2O) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Compliance | 31 | 31 | 33 | 43 | 46 | 30.9 | 29 | 30.9 | – | – | 20 | 25 | 25 | 34 | 23 |

| P/F | 136 | 106 | 125 | 130 | 154 | 87 | 97 | 87 | – | – | 100 | 118 | 224 | 112 | 120 |

| Blood gas values | |||||||||||||||

| pH | 7.22 | 7.2 | 7.28 | 7.31 | 7.4 | 7.16 | 7.2 | 7.16 | 7.1 | – | 7.39 | 7.34 | 7.38 | 7.39 | 7.42 |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 95.3 | 74.6 | 87.5 | 78.5 | 77.3 | 48.5 | 65.8 | 67 | 67 | – | 49.8 | 45.7 | 101 | 56 | 67.2 |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 60.7 | 64.7 | 51.9 | 40.9 | 38.8 | 62.6 | 52.9 | 40 | 92 | – | 39.5 | 59.1 | 41 | 41 | 40.2 |

| HCO3 (mmol/l) | 24.1 | 24.1 | 23.7 | 20 | 23.5 | 21.5 | 19.9 | 13.6 | 20.7 | – | 23.8 | 24.4 | 23.2 | 24.7 | 25.3 |

| Lactate (mmol/l) | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.5 | – | 2.7 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.3 |

| ECCO2R parameters | |||||||||||||||

| Blood flow (ml/min) | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 | 280 | 400 | 300 | 350 | – | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 |

| Sweep gas flow (l/min) | 0 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 10 | – | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Hemodynamic parameters | |||||||||||||||

| MBP (mmHg) | 84 | 75 | 97 | 95 | 80 | 65 | 75 | 80 | 55 | – | 70 | 75 | 65 | 60 | 70 |

| HR (bpm) | 106 | 92 | 79 | 70 | 73 | 110 | 90 | 80 | 100 | – | 55 | 60 | 60 | 65 | 50 |

| Noradrenaline (µg/kg per min) | 0 | 0.44 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.36 | – | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.26 |

| Dobutamine (µg/kg per min) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sedation and analgesia | |||||||||||||||

| Midazolam | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Propofol | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | – | No | No | No | No | No |

| Fentanyl | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cisatracurium | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

ECCO2R: extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal; HR: heart rate; MBP: mean blood pressure; P/F: PaO2/FiO2.

The use of VV ECMO was contraindicated in all three cases due to the patient age and lung disease without predictable recovery (important bronchiectasis in Kartagener syndrome) in the first case, and comorbidities (active malignant disease) in the other two cases.2

Ventilatory management with APRV was carried out following the clinical guidelines of Habashi3 for the transition from conventional ventilation to APRV (P high = plateau).

In APRV, the ventilator is equipped with an active expiratory valve that allows spontaneous breathing of the patient in any of the pressure phases, and the duration of the “high pressure” phase is always longer than that of the “low pressure” phase – this being equivalent to an inverted I:E ratio.4

In relation to mechanical ventilation injury, Protti et al. found that, for a given total amount of strain, a higher static strain component (PEEP, air trapping) results in lesser lung injury than the use of dynamic strain.5

In theory, APRV allows the patient to spend most of the time in a situation of high static strain (P high) and low dynamic strain; consequently, the risk of lung injury should decrease in comparison with the conventional modes that give rise to low static strain and high dynamic strain.6

However, caution is required when interpreting the effect of spontaneous breathing in APRV in the context of lung injury, since a number of factors intervene: the combination of spontaneous and mandatory respirations, adjustment of the ventilator, and the degree of lung injury. Neumann et al., on analyzing the possible adverse effects of APRV, found that spontaneous respiration could cause very high tidal volume (VT) and pleural pressure changes, which would be associated to high transpulmonary pressures and an increased risk of ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI).7 These aspects sometimes oblige an increase in patient sedation, or even the use of relaxation.

In our three scenarios, the combination of prior muscle relaxation with the consequent absence of spontaneous respiration, the decrease in functional lung parenchyma and the inverted I:E ratio in APRV appear to inevitably require the adoption of measures to counter the increase in PaCO2 and control its harmful effects upon the lung, such as delayed alveolar repair after lung injury, decreased alveolar fluid reabsorption rates, and the inhibition of alveolar cell proliferation.8

An alternative in these situations is the use of carbon dioxide removers. In our case, and in view of the need for RRT due to different reasons, ECCO2R-RRT was the treatment used.

In our three patients, following the decision to start ECCO2R-RRT, and after priming, the device was connected to the patient and the extracorporeal blood flow was progressively increased to 400 ml/min. The sweep gas flow across the membrane was kept at 0 l/min during this phase, as a result of which no CO2 was initially removed.

Promising results have been documented with ECCO2R-RRT in animals and in small studies involving patients with ARDS,9 and the technique requires no specific large-caliber venous accesses. Due to its low flow, this technology does not allow adequate extracorporeal oxygenation. However, a flow of 350–500 ml/min suffices to eliminate half of the production of CO2; consequently, ECCO2R is an interesting tool in such situations.7,10

Financial supportThe present study has received no funding of any kind.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: González-Castro A, Escudero Acha P, Rodríguez Borregán JC, Peñasco Y, Blanco Huelga C, Cuenca Fito E. Combinación de la ventilación con liberación de presión con la relación inspiración-espiración invertida y los dispositivos de eliminación de CO2 de bajo flujo con terapia de sustitución renal en la hipoxemia refractaria. Med Intensiva. 2021;45:376–379.