To analyze the presence of frailty in survivors of severe COVID-19 admitted in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and followed six months after discharge.

DesignAn observational, prospective and multicenter, nation-wide study.

SettingEight adult ICU across eight academic acute care hospitals in Mexico.

PatientsAll consecutive adult COVID-19 patients admitted in the ICU with acute respiratory failure between March 8, 2020 to February 28, 2021 were included. Frailty was defined according to the FRAIL scale, and was obtained at ICU admission and 6-month after hospital discharge.

InterventionsNone.

Main variables of interestThe primary endpoint was the frailty status 6-months after discharge. A regression model was used to evaluate the predictors during ICU stay associated with frailty.

Results196 ICU survivors were evaluated for basal frailty at ICU admission and were included in this analysis. After 6-months from discharge, 164 patients were evaluated for frailty: 40 patients (20.4%) were classified as non-frail, 67 patients (34.2%) as pre-frail and 57 patients (29.1%) as frail. After adjustment, the need of invasive mechanical ventilation was the only factor independently associated with frailty at 6 month follow-up (Odds Ratio [OR] 3.70, 95% confidence interval 1.40–9.81, P = .008).

ConclusionsDeterioration of frailty was reported frequently among ICU survivors with severe COVID-19 at 6-months. The need of invasive mechanical ventilation in ICU survivors was the only predictor independently associated with frailty.

Analizar el deterioro de fragilidad en sobrevivientes de COVID-19 grave ingresados en la Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos (UCI) a los seis meses después del alta.

DiseñoEstudio observacional, prospectivo y multicéntrico, de ámbito nacional.

ÁmbitoOcho UCI en ocho hospitales académicos en México.

PacientesSe incluyeron todos los pacientes adultos consecutivos con COVID-19 ingresados en la UCI con insuficiencia respiratoria aguda entre el 8 de marzo de 2020 y el 28 de febrero de 2021. La fragilidad se definió según la escala FRAIL y se obtuvo al ingreso en la UCI y 6 meses después del alta hospitalaria.

IntervencionesNinguna.

Variables de interés principalesEl objetivo principal fue la fragilidad a los 6 meses después del alta. Se utilizó un modelo de regresión logística para evaluar los predictores durante la estancia en UCI asociados con la fragilidad.

Resultados196 supervivientes de la UCI se incluyeron en el análisis. A los 6 meses desde el alta, 164 pacientes fueron evaluados: 40 pacientes (20,4%) fueron clasificados como no frágiles, 67 (34,2%) como prefrágiles y 57 pacientes (29,1%) como frágiles. La necesidad de ventilación mecánica invasiva fue el único factor asociado independientemente con la fragilidad a los 6 meses de seguimiento (Odds Ratio [OR] 3,70; intervalo de confianza del 95%: 1,40 a 9,81, P = ,008).

ConclusionesEl deterioro de la fragilidad aparece globalmente en más de la mitad de los supervivientes de la UCI con COVID-19 grave a los 6 meses. La necesidad de ventilación mecánica invasiva en los supervivientes de la UCI fue el único predictor asociado independientemente con la fragilidad.

Frailty is a common syndrome with multiple causes and risk factors that is characterized by diminished strength, a decline in psychologic condition and cognition.1 These abnormalities increases an individual's vulnerability for developing increased dependency and/or mortality. Although frailty is commonly found in old adults with a prevalence of 7.4%, its not limited to the elderly.2 Muscedere et al. found that frailty was associated with 1.71-fold increase of in-hospital mortality compared with non-frail individuals patients in the ICU, which indicated that routine assessment of frail patients would contribute to high survival and recovery rate in ICU.3

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has generated an unexpected number of critically ill patients admitted to Intensive Care Units (ICU) for treatment of acute severe respiratory failure.4,5 As a result of this situation, many survivors of critical illness experienced physical function or psychological disability probably related with prolonged ICU stay.6 An increasing body of research has been published to describe the clinical features and predictors of mortality in people with COVID-19.7–9 In these studies, older age has consistently been shown to be associated with poor outcomes, with increasing mortality linked to an older age. Age is a simple prognostic tool because it is easy to measure, however, we previously showed that on an individual level, age alone has little prognostic use.10,11

No information is available on the influence of ICU treatment in the assessment of frailty in patients with COVID-19 admitted to hospital. Such evidence will aid and support physicians in decision making with this complex group of patients.

The main objective of the study was to explore the change in prevalence of frailty in a cohort of patients with severe COVID-19 admitted to intensive care at 6 months of hospital discharge.

MethodsStudy designAn observational, prospective, multicenter and national study conducted in 8 ICU from eight academic hospitals from Mexico including consecutive adult patients admitted to the ICU due to acute hypoxemic respiratory failure secondary to SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia between March 8, 2020–February 28, 2021. Patients with a acquired neuromuscular disease were excluded. The diagnosis was confirmed by positive result of real time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing of a nasopharyngeal swab.

Data collectionThe presence of frailty was specifically addressed. Frailty was defined according to the FRAIL scale (FS) definition and was obtained at admission to the ICU and 6-month after discharge from the ICU, and included five-item12: fatigue, resistance, ambulation, illnesses, and weight loss adapted and validated for Spanish language and Mexican population13 (eFig. 1 in Supplementary Appendix). The information was obtained from standardized interviews with patients or surrogate respondents in cases of inability to answer due to the need for invasive mechanical ventilation or sedation.

The FRAIL scale is a subjective judgment-based screening tool for frailty that has been proved to be valid, reliable, simple to perform, validated and successfully adapted to Mexican Spanish. For the purpose of the analysis, the categorization of this scale was as follows: health status zero point was considered as robust (non-frail), with to two points were considered pre-frail, and when three or more points were obtained, the participant was cataloged as frail. The follow-up to monitor frailty was performed at 6 months after discharge hospital through a telephone interview. Participants with missing data for one or more frailty criteria were excluded.

The primary endpoint was the frailty status assessed at 6-months after hospital discharge in ICU survivors. The secondary outcomes were the development of complications and organ failure during the ICU stay, ICU mortality, and 6-month mortality rates.

Study personnel at each site collected data by manual review of medical records and used a standardized case report form to enter data into a secure online database.

The clinical variables recorded were: age, sex, height, weight, severity at admission estimated by Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS2) which ranges from 0 [lower severity] to 150 [higher severity], comorbidities (asthma, COPD, other chronic pulmonary disease, chronic renal disease, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity, chronic cardiac failure, ischemic cardiomyopathy, permanent atrial fibrillation, cirrhosis, ischemic stroke, immunosupression, hematological neoplasia, autoimmune disease, HIV infection), chronic medication (angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, statins, antiplatelet therapy, oral anticoagulants, steroids), mode of respiratory support (high flow nasal cannula therapy and/or noninvasive positive pressure ventilation [NPPV]), and compassionate medication received [antivirals (lopinavir-ritonavir, hydroxychloroquine, remdesivir) and immunomodulatory agents (interleukin-6 receptor antagonists, Janus kinase inhibitor, and corticosteroids)], length of hospital stay prior to ICU admission, date of intubation, ventilatory settings within first week of mechanical ventilation, daily arterial blood gases, concentrations of plasma-based and serum-based biomarkers drawn within 7 days of ICU admission, including high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, d-dimer, ferritin, high-sensitivity troponin, procalcitonin, and IL-6, use of adjuvant therapies for acute respiratory failure (neuromuscular blocking agents, inhaled pulmonary vasodilators, prone-positioning ventilation, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation), antiviral agents, and immunomodulatory agents, complications and organ dysfunction during the ICU stay.

The subjects were followed up to 6 months to assess for frailty and status outcomes.

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Board of each participating site, and waived the requirement for informed consent from individual patients considering the study design as minimal-risk research using data collected for routine clinical practice and ongoing public health emergency. All data except dates were deidentified.

The study was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04379258. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement guidelines for observational cohort studies.14

Statistical analysisThe main outcome was the changes in frailty score 6 months after hospital discharge and to estimate the variables associated to increase of the FS.

Descriptive statistics were expressed by quantitative data as mean with standard deviation (SD) or median (IQR), and qualitative data as absolute and relative frequencies (proportions, %). To test for statistical association between baseline FS states (ordinal variable) and participant characteristics, the ANOVA or Willcoxon test were used for continuous and ordinal variables as required, and the Chi-squared test for trend test for dichotomous variables.

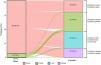

For the visualization of the longitudinal trajectories of the three frailty states components, alluvial charts were created using the R alluvial package. In each alluvial plot, the height of the stacked bars at each wave (which represent whether participants’ status for the given frailty state or component was yes, no, missing or died) is proportional to the number of participants identified as belonging to this state at each wave. The thickness of the streams connecting the stacked bars between waves are proportional to the number of participants who have the state identified by both ends of the stream.

To evaluate the predictive variables during ICU admission associated with frailty (estimated from robust category to frail or prefrail categories, and from prefrail category to frail), a multivariate analysis was performed, using logistic regression models and taking as dependent variables the development of frailty at 6 months after discharge. In turn, the independent variables were defined as those variables that were identified in the univariate analysis as being associated to the outcomes of interest (frailty) with a value P < .10, as well as those variables of clinical interest. Since the number of variables to be entered in the multivariate model were limited by the prevalence of the outcome, we were only able to include one to two variables. For this reason, fitting of the model (maximum model) was limited to: sex, immunesupression, chronic renal disease, cardiopathy, SAPS2 score, basal assessment of frailty, duration (in days) of hospital stay prior to ICU admission, need of invasive ventilatory support, use of neuromuscular blockers, and prone positioning.

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the estimated covariate effects of age, sex, SAPS2, tracheotomy and duration of ventilatory support were obtained. ORs were considered significant when their CIs did not include 1.

Statistical significance was considered at P < .05. Except for the alluvial graph, analyses were performed using Stata version 17.0 (StataCorp LLC).

ResultsBaseline characteristicsIn the period of study 524 patients were enrolled. From those, 194 patients (37%) who died during their hospital stay were excluded from the study. From the cohort of 330 survivors, 196 patients had an evaluation for frailty at admission in the ICU, and finally included in this analysis (Fig. 1). Baseline characteristics are showed in Table 1. Of these, 139 (71%) were male, 17 (9%) were older than 75 years, 65% received invasive mechanical ventilation and the median duration of ventilatory support was 8 days (IQR, 6–12 days).

Baseline characteristics of patients included in the analysis.

| Survivors | |

|---|---|

| N = 196 | |

| Age, mean (SD), median (p25, p75), years | 54 (14) |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 139 (71) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m2, median p25, p75 | 29.9 (5.3) |

| SAPS2, mean (SD), points | 44 (14) |

| Comorbidities, No (%) | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 2 (1.0) |

| Hypertension | 64 (32) |

| Obesity | 77 (39) |

| Diabetes | 53 (27) |

| Dyslipemia | 0 |

| Chronic pulmonary obstructive disease | 2 (1.0) |

| Cirrhosis | 2 (0.4) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0 |

| Immunodepression | 3 (1.5) |

| Severity | |

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio, median (P25, P75) | 147 (99, 206) |

| Severity of acute respiratory distress syndrome* | |

| Mild | 45 (22.9) |

| Moderate | 77 (50.7) |

| Severe | 43 (28.3) |

| Unknown | 31 (15.8) |

| Respiratory support, No (%) | |

| High flow nasal cannula | 41 (20.9) |

| Noninvasive ventilation | 28 (14.2) |

| Invasive ventilation | 127 (64.7) |

| Days from initiation symptoms to hospital admission, median (P25, P75) | 8 (7, 11) |

| Days from hospital admission to orotracheal intubation, median (P25, P75) | 1 (0, 3) |

| Basal Frailty scale before ICU admission, No (%) | |

| No frail | 181 (92.3) |

| Pre-frail | 14 (7.1) |

| Frail | 1 (0.5) |

SAPS, Simplified Acute Physiologic Score. SD, standard deviation.

The complications, during ICU stay and outcomes are shown in Table 2. The characteristics of patients that were not included in the analysis are shown in eTable 1 and eTable 2 in Supplementary Appendix.

Early complications (within first seven days of ICU stay) and clinical outcomes in survivors.

| Survivors | |

|---|---|

| N = 196 | |

| Complications | |

| Cardiovascular dysfunction | 60 (30.6) |

| Acute pulmonary thromboembolism, No (%) | 2 (1) |

| Pneumothorax, No (%) | 3 (1.5) |

| Renal replacement therapy, No (%) | 1 (0.5) |

| Clinical Events # | |

| Scheduled extubation, No (%) | 121 (61.7) |

| Reintubation, No (%) | 10 (8.2) |

| Tracheotomy, No (%) | 13 (10.2) |

| Percutaneous | 11 (84.6) |

| Surgical | 2 (15.0) |

| Clinical outcomes | |

| Duration of invasive mechanical ventilation, days, median, p25, p75 | 8 (6, 12) |

| Length of ICU stay, days, median (p25, p75) | 10 (7, 15.5) |

| Length of hospital stay, median (p25, p75) | 15 (8, 22) |

| ICU readmission, No (%) | 1 (0.5) |

| 6-months mortality, No (%) | 11 (6.3) |

At ICU admission the baseline frailty was as follows: 181 patients (92%; 95% confidence interval [CI] 88%–96%) were classified as non-frail, 14 patients (7%; 95% CI 4%–12%) as pre-frail and 1 patient (0.5%; 95% CI 0.01%–2%) as frail. The prevalence of frailty status for each age category increased with age (robust was defined in 30% of older than 60 years old, prefrail affected 35% of patients older than 60 years, and frail in 100% of patients older than 60 years) (eTable 3, in Supplementary Appendix).

Analysis of frailty over time in ICU survivorsThe alluvial plots are shown in Fig. 2. The cumulative proportion of frailty increased over time. At 6-months after discharge from the ICU, 164 patients were evaluated for frailty: 40 patients (24%) were classified as robust, 67 patients (41%) as pre-frail and 57 patients (35%) as frail (Fig. 2). In total, 114 patients (69%) worsened their condition after ICU admission.

Table 3 shows the univariate analysis of the comparison between patients who showed deterioration in frailty score at six months (n = 114) versus those who did not have deterioration after ICU treatment (n = 50). Significant differences were found in the severity scale at ICU admission (SAPS2), in the treatment used (propofol infusion, continuous analgesics infusion and neuromuscular blockers use), and in the CPR levels at ICU admission.

Univariable model for patients who develop frailty at 6 months of follow up in survivors.

| Variable | No deterioration | With deterioration | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 50 | N = 114 | ||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 53 (17) | 52 (13) | .913 |

| Sex, male, No (%) | 31 (62.0) | 80 (70.2) | .303 |

| SAPS2 at ICU admission, points, mean (SD) | 35.2 (11.5) | 39.2 (10.8) | .041 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 30.0 (5.9) | 29.7 (5.0) | .812 |

| Comorbidities, No (%) | |||

| Asthma | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | .546 |

| COPD | 0 | 2 (2) | |

| Diabetes | 17 (34) | 27 (24) | .170 |

| Hypertension | 16 (32) | 34 (30) | .781 |

| Obesity | 21 (42) | 44 (39) | .682 |

| Ischaemic cardiopathy | 1 (2) | 0 | |

| Stroke | 0 | 2 (2) | |

| Cancer | 2 (4) | 0 | |

| Immunosuppresion | 0 | 6 (5) | |

| Prone positioning, No (%) | 10 (20) | 27 (24) | .603 |

| Continuous sedative infusion, No (%) | |||

| Benzodiazepines | 9 (18) | 29 (25) | .299 |

| Propofol | 13 (26) | 54 (47) | .010 |

| Dexmedetomidine | 8 (16) | 29 (25) | .183 |

| Continuous Analgesics infusion, No (%) | 13 (26) | 54 (47) | .010 |

| Corticosteroids, No (%) | .450 | ||

| Methylprednisolone ≥ 1 mg/kg | 4 (8) | 4 (4) | |

| Methylprednisolone < 1 mg/kg | 16 (32) | 41 (36) | |

| Continuos infusion of neuromuscular blockers, No (%) | 9 (18) | 35 (31) | .091 |

| Reintubation, No (%) | 3 (19) | 6 (8) | .191 |

| Tracheotomy, No (%) | 3 (6) | 6 (5) | .849 |

| Lung protective ventilator strategy, No (%) | 12 (24) | 40 (35) | .160 |

| PaO2FiO2 ratio at ICU admission, mean (SD) | 150.5 (138) | 167.7 (92) | .442 |

| SpO2FiO2 at ICU admission, mean (SD) | 158.2 (82) | 181.7 (92) | .228 |

| Driving pressure, cm water, mean (SD) | 12.1 (5.6) | 10.5 (5.4) | .305 |

| Dimer-D at ICU admission, mg/L, median (IQR) | 1.74 (0.6, 576.0) | 2.2 (0.64, 721.0) | .390 |

| CRP, mg/mL, at ICU admission, mean (SD) | 146 (101) | 200 (134) | .026 |

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRP, c-reactive protein; SD, standard deviation.

The adjusted analysis showed that baseline frailty was not associated with ICU mortality (OR 0.43; 95% CI 0.11–1.59, P = .207).

Association between frailty among COVID-19 survivors from ICU treatmentAfter adjustment of basal covariates and those related with ICU treatment, the need of invasive mechanical ventilation was independently associated with frailty at 6 months of follow-up (Odds Ratio [OR] 3.70, 95% confidence interval 1.40–9.81, P = .008) (Fig. 3).

The sensitivity analysis that included the baseline frailty assessment did not show differences in the predictive variables associated with the deterioration of frailty at 6 month after hospital discharge, and was associated as well independently with the impairment of frailty (OR 0.03; 95% CI 0.01−0.18, P < .01) (eFig. 2 in Supplementary Appendix).

DiscussionThe main findings of this observational prospective cohort study including critically ill patients from 8 hospitals in Mexico who survived 6 months following ICU stay due to COVID-19 are that frailty worsening after 6 months affected up to 63% of patients and therefore, only a fifth remained robust. At the same time, we found that only the need of invasive ventilatory support was independently associated with frailty at 6 months post discharge.

Studies in patients who survived ICU admission from severe COVID-19 have focused on clinical outcomes as disability, pulmonary function impairment and mortality rates8,15–18 and have found a high rate of clinical sequelae in patients with COVID-19 after hospital discharge. However, there is no information available regarding the impact of frailty over time in severe COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU mainly due to small sample sizes, or heterogeneity in frailty determination criteria. A recent individual patient data meta-analysis that included 2001 patients admitted to ICU with coronavirus disease 2019 and found that frailty patients had worse clinical outcomes such as a greater hospital mortality when compared with non-frail patients (65.2% vs 41.8%; P = .001, respectively).19 To our knowledge, this is the first well-characterized descriptive, observational study to assess frailty of COVID-19 survivors who underwent ICU stay over time. Recently, a prospective uncontrolled cohort study that included 478 survivors of COVID-19 who had been hospitalized in a university hospital in France, and underwent a telephone interview 4 months after discharge found that half of patients declared to have one symptom that did not exist before COVID-19 as long-term sequelae,20 in contrast our study found 75% of frailty deterioration (from robust category to pre-frail or frail categories and from pre-frail to frail category) at 6 months among ICU survivors with COVID-19.

Frailty has been previously evaluated in critically ill patients admitted in the ICU.21–25 It is well known that frailty is associated with a significant higher hospital mortality rate in critically ill patients. However, it is unclear whether frailty screening on admission to the ICU can be useful as a prognostic tool. A recent study evaluated the association between baseline assessment of frailty scores and disability in instrumental activities of every day living in critically ill patients, and found that those patients with worse clinical frailty before developing critical illness were 20% and 30% less likely to be able to carry out instrumental activities of every day living at 3 and 12 months, respectively.26 In the present study, the majority of patients experienced a decrease in frailty categories, and only 20.4% of robust patients at ICU admission remained in the same category after 6 months of ICU treatment, which highlighted the clinical relevance of the assessment of frailty at baseline. Moreover, risk stratification should not be based on age alone but should include a frailty assessment.27

Another important finding of this study is that none of the baseline characteristics of survivors were significantly associated with worsening of frailty at 6 months when invasive ventilatory support was taken into account. In fact, only the need of invasive mechanical ventilation in severe COVID-19 patients had an independent three fold increase in the odds of frailty at 6-month follow-up. Likewise, the ICU survivors resulted in a worse physical health-related quality of life at 1-year follow-up.28 On the other hand, despite pre-ICU health status could be associated with post-ICU health problems, the baseline frailty status itself prior to ICU admission could be also considered as a risk factor for the deterioration of ICU survivors. However, our results based on the sensitivity analysis of the predictive model have shown that basal frailty is not independently associated with the deterioration. Further studies however should be addressed to establish the specific association between the baseline frailty status with the deterioration of health status after ICU admission in a long-term follow-up.

The strength of these independent associations was not affected by age, indicating that patients of all ages along the fitness to frail continuum are at risk for poor outcomes after critical illness, regardless the reason for the ICU admission.

This study may set the starting point for future work in several ways. Whereas frailty has frequently been used for screening and risk stratification in clinical subpopulations,29 our findings suggest that frailty may be a useful measure of risk of clinical worsening among a broader population of critically ill patients after ICU stay.

While this study provides potentially important insights, there are limitations that should be considered. First, limitations in data availability prevented us from evaluating the role of underlying factors, such as chronic inflammation, nutrition, medications, or genetics, which may explain or mediate associations between frailty and worsening of clinical functional outcomes. Second, these findings are limited by the absence of a control group and, because it is unclear whether COVID-19 showed a unique phenotype and implication in a different risk stratification of impairment of frailty in survivors. The limited information in the literature on the effect of ICU treatment on fragility related with any reason and critically ill phenotype adds relevance to our study. Further research is needed to understand longer-term outcomes and whether these findings may reflect associations with the disease.

Third, this study has been validated in community-dwelling Mexican adults, but post-ICU care, the local clinical practices, and the Mexican Health Care System itself may limit the registry of the results.

ConclusionsFrailty score deterioration was reported frequently among survivors critically ill patients with severe COVID-19 at 6 months. Frailty needs to be recognized and integrated into the management of patients admitted to the ICU to better understand the implications and outcomes of prehospital frailty status among younger critically ill patients, and will provide relevant prognosis that would contribute to a better-informed decision-making. Further studies will guide innovative research focused on interventions in order to prevent or decrease the risk of deterioration of frailty in critically ill patients.

Conflicts of interest and fundingÓscar Peñuelas has received a grant (#12345) from Foundation for Biomedical Research of the University Hospital of Getafe, Spain (COVID-19 No. ISCIII:COV20/00977, 2020. Madrid (0010604). The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any conflicts of interest or any industry relationships for past 2 years.

Author’s contribution to the studyOP, FFV, LCA and AM take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. ML, OP, FFV, AM, LCA and AE conceived, designed and coordinated the research. ML, ST, AA, UC, MCM, KR, MA, GM, RM, HG-L, EM, DG, JP were responsible for data acquisition. AEF contributed to the database, software, and the website. LCA and AM performed statistical analysis, and OP, FFV, ML, AR were responsible of data interpretation. OP, ML and LCA drafted the manuscript. All authors participated in collection of data, critically revised the draft of the manuscript, reviewed and approved the final version and agreed to submit the manuscript for publication.

The authors would like to thank all the ICU physicians, nurses, and health care personnel for their commitment and solidarity at all times during the outbreak of COVID-19 despite the limitations in health resources and the crisis.