Clinical frailty is a syndrome characterized by a reduction in physical activity, physiological function, and cognitive reserve, with molecular and physiological characteristics including increased inflammatory markers.1

The frail individual presents, in varying combinations, reduced mobility, loss of muscle mass, poor nutritional status, and a decreased cognitive function.2 Each of these factors and their combination make the individual more susceptible to extrinsic stressors, resulting in higher all-cause mortality vs non-frail individuals of the same age range.3 Although frailty is more prevalent in older individuals (25% in those older than 65 years vs 50% in those older than 85 years),4 frailty and aging are not synonymous. Therefore, to determine the true prevalence of frailty at the intensive care units (ICU) setting, all patients admitted to these units must be considered.

According to the recent EDEN-12 study,5 the chances of hospital admission for patients seen at the ER decrease significantly after 83 years of age, which may also affect ICU admission probability. However, current demographics impose a considerable increase in the population of elderly patients in ICUs of Western societies, and the likelihood of frail patients being admitted to these medical services alone justifies the researchers' interest in evaluating the impact of frailty on the chances of all-cause mortality and other outcomes.6

In the last five years, studies conducted with patients admitted to Spanish ICUs7,8 have focused on evaluating the prevalence of frailty and its relationship with mortality prediction. We find it interesting to communicate the frailty data referring to a population of 4512 patients who were consecutively admitted to 7 Spanish ICUs from January 2019 through January 2020. The contribution to the sample size from each hospital is shown in Table 1Appendix A. The study was approved by the ethics committee and a waiver for Informed Consent was granted.

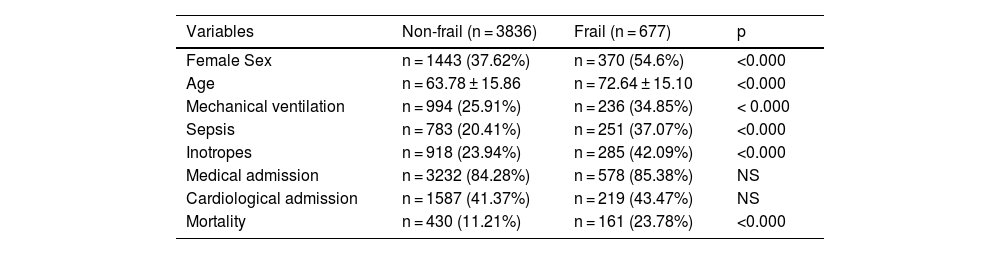

Comparison of variables in frail vs non-frail patients.

| Variables | Non-frail (n = 3836) | Frail (n = 677) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female Sex | n = 1443 (37.62%) | n = 370 (54.6%) | <0.000 |

| Age | n = 63.78 ± 15.86 | n = 72.64 ± 15.10 | <0.000 |

| Mechanical ventilation | n = 994 (25.91%) | n = 236 (34.85%) | < 0.000 |

| Sepsis | n = 783 (20.41%) | n = 251 (37.07%) | <0.000 |

| Inotropes | n = 918 (23.94%) | n = 285 (42.09%) | <0.000 |

| Medical admission | n = 3232 (84.28%) | n = 578 (85.38%) | NS |

| Cardiological admission | n = 1587 (41.37%) | n = 219 (43.47%) | NS |

| Mortality | n = 430 (11.21%) | n = 161 (23.78%) | <0.000 |

NS, not significant.

This population was recruited in the context of an external validation study of a mortality score,9 and all patients were assessed for the presence of frailty defined according to the CSHA (Canadian Study of Health and Aging) criteria.3 Patients with scores of 1 and 2 were categorized as non-frail, pre-frail (scores of 3 and 4), and frail (scores of ≥5) (the items of the scale are shown in Supplementary material Fig. S1 of the Appendix A).

Applying these criteria retrospectively to the 4512 patients, 2 populations were defined: non-frail (n = 3836) and frail or pre-frail (n = 677), which is representative of 15% of the entire sample.

This prevalence, which is consistent with the lowest one described in the literature,6 should be viewed from the perspective that it is calculated over the entire population admitted during the study period, not taking into consideration age ranges, and with the previously described frailty definition criteria.

The populations of patients with and without frailty criteria are clearly different in all factors considered in the study (sex, age, mechanical ventilation, sepsis, inotropes, medical admission, cardiology admission, and mortality), except for the medical origin of the patients (Table 1). Frail/pre-frail patients are older, there is a higher prevalence of female sex as found by other authors,10 are more likely to present sepsis, have higher resource consumption in the form of inotrope infusion or mechanical ventilation, and have a higher all-cause mortality rate at the ICU setting. The overall all-cause mortality is 23.78%, which is very close to the meta-analysis conducted by Muscedere.6

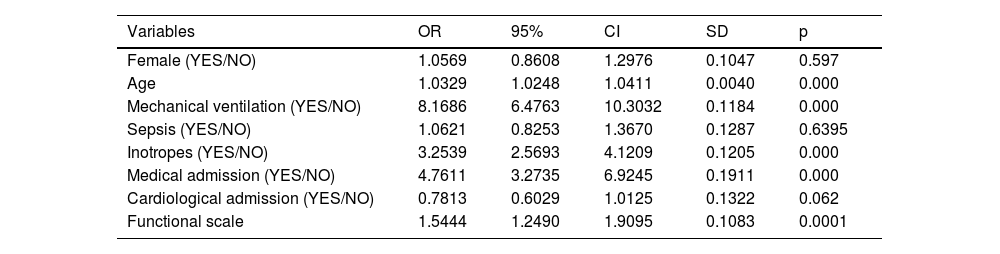

Unconditional logistic regression using all-cause mortality as the dependent variable (Table 2) establishes the weight of frailty as a prognostic factor for all-cause mortality at the ICU setting [OR, 1.63 (1.36–1.97); p < 0.0000]. This value is in line with that found by Muscedere et al.6 and is clearly higher than that of age [OR, 1.02 (1.01–1.03); p < 0.0000].

Logistic regression with mortality as the dependent variable applied to the overall sample (n = 4512).

| Variables | OR | 95% | CI | SD | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (YES/NO) | 1.0569 | 0.8608 | 1.2976 | 0.1047 | 0.597 |

| Age | 1.0329 | 1.0248 | 1.0411 | 0.0040 | 0.000 |

| Mechanical ventilation (YES/NO) | 8.1686 | 6.4763 | 10.3032 | 0.1184 | 0.000 |

| Sepsis (YES/NO) | 1.0621 | 0.8253 | 1.3670 | 0.1287 | 0.6395 |

| Inotropes (YES/NO) | 3.2539 | 2.5693 | 4.1209 | 0.1205 | 0.000 |

| Medical admission (YES/NO) | 4.7611 | 3.2735 | 6.9245 | 0.1911 | 0.000 |

| Cardiological admission (YES/NO) | 0.7813 | 0.6029 | 1.0125 | 0.1322 | 0.062 |

| Functional scale | 1.5444 | 1.2490 | 1.9095 | 0.1083 | 0.0001 |

CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

We must highlight the fact that, unlike in the meta-analysis conducted by Muscedere et al.,6 our frail population does show higher therapeutic resource consumption in the form of mechanical ventilation or inotrope infusion, which intuitively seems more reasonable than admitting that 2 such different populations show no differences in resource consumption. We should mention that our overall sample size is larger, thus reducing the probability of type I error.

Differences between frail and pre-frail patients were also analyzed, although this analysis is hampered by the fact that the frail group includes 61 patients only, and consequently, the probability of type I error cannot be ignored. Considering this premise, frail patients show a distinguishing feature of a higher percentage of sepsis [OR, 1.86 (1.09–3.15); p = 0.02]. Other analyzed factors do not reach statistically significant differences, though we considered it interesting to present them in the corresponding table (Table 2Appendix A) to the readers. The fact that the frail subgroup of patients has a higher rate of sepsis—and this does not correspond to higher resource consumption—should be attributed to the small sample size of the frail patients. The admission of frail patients to our ICUs is an undeniable and frequent fact. It is reasonable to assume that the current prevalence will increase in line with the aging population. It is obvious that the presence of frailty cannot constitute an exclusion criterion for admission, but one must consider that the increasing prevalence of this population has individual prognostic implications and conditions greater therapeutic resource consumption, factors that should be taken into account in the present and future planning of our ICUs.

Conflicts of interestThe authors of the paper "FRAILTY, AND PREVALENCE IN OUR INTENSIVE CARE UNITS AND DIFFERENTIAL CHARACTERISTICS OF FRAIL PATIENTS" declared no conflicts of interest and no funding sources in relation to the scientific letter we are presenting.