To assess compliance with hand hygiene (HH) in ICU workers before (P1) and after (P2) implementation of a HH promotion program and distribution of an alcoholic solution for HH, and to analyze factors independently associated to HH before and after patients care.

DesignObservational evaluation for 50h of was carried out during each period of the study (P1 and P2); the number of opportunities for HH (before and after patients care) was registered. Educational program (6 months): poster campaign, educational meetings with staff about HH, and the provision of alcohol hand rubs.

SettingICU in a secondary level hospital.

ParticipantsHealthcare workers in the ICU.

InterventionsA quasi-experimental design was used to evaluate compliance with HH before and after implementation of the educational program.

VariablesDependent variable: HH compliance before–after patients care; independent variables that might be associated to compliance (including the educational program).

ResultsIn P1, there were 338 opportunities for HH both before and after patients care, versus 355 in P2 (before and after patients care). The hand-washing rate was significantly higher in P2 than in P1 (prior to patient care: 45.3% and 34.9%, respectively, and after patient care: 63% and 51.7%, respectively). In the multivariate analysis, the educational program, together with other variables, was significantly associated to HH before and after patients care.

ConclusionThere was a significant increase in compliance with hand hygiene among the ICU personnel during the educational phase, both before and after patients care.

Evaluar el cumplimiento de las recomendaciones sobre «higiene de manos» (HM) en una unidad de cuidados intensivos (UCI) en una fase previa (F1) y posterior (F2) a la intervención descrita y analizar los factores asociados de forma independiente al cumplimiento de dichas recomendaciones (antes y después del contacto con el paciente).

DiseñoCincuenta horas de observación en F1 y F2; programa de intervención (PI) (6 meses) que incluye la distribución de dispensadores de solución alcohólica.

ÁmbitoUCI de un centro asistencial de segundo nivel.

ParticipantesPersonal sanitario de la UCI.

IntervencionesEstudio cuasi experimental que evalúa la situación antes y después de un PI para mejorar el cumplimiento de la HM.

Variables de interésVariable dependiente: cumplimiento de la HM antes-después del contacto con el paciente; variables independientes que pudieran influir en dicha pauta (entre ellas el PI).

ResultadosEn F1 se recogieron 338 oportunidades para la HM (antes y después del contacto con el paciente); la HM se realizó en 118 (34,9%) y 175 (51,7%), respectivamente. En F2 se observaron 355 oportunidades (antes y después del contacto con el paciente), realizándose la HM en 161 (45,3%) y 224 (63%), respectivamente. En el análisis multivariado la presencia de un PI se asoció de forma independiente, junto con otras variables, con la realización de la HM antes y después del contacto con el paciente.

ConclusionesLa introducción de un PI sobre HM en una UCI aumenta de forma estadísticamente significativa el porcentaje de actos de HM antes y después del contacto con el enfermo.

Nosocomial infections (NIs) are a determinant factor in reference to patient safety, since they increase morbidity–mortality, the healthcare costs per disease process, and prolonged hospital stay, and are moreover correlated to antibiotic resistance phenomena.1–4 NIs acquire particular relevance in hospital admission areas such as Intensive Care Units (ICUs), where their incidence is 2–5 times higher than in the rest of the hospital population,4,5 reaching incidences of 17%, with attributable mortality rates of 20–50%.

In 1847, Semmelweis conducted the first experimental study showing that appropriate hand hygiene (HH) prevents puerperal infection and maternal mortality. Posteriorly, different studies have shown HH compliance to reduce the frequency of NIs and reinforce patient safety in all situations–from the most advanced healthcare systems to the least privileged healthcare settings.6–11

The 57th Assembly of the World Health Organization (WHO), held in May 2004, approved the creation of an international alliance to improve patient safety. The Alliance for Patient Safety was founded shortly afterwards, in October of that same year, with recognition of the universal need to improve HH in healthcare institutions, and the development of a strategy included in the WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Healthcare (advanced draft), under the heading “Clean hands are safe hands”.12

Although there is sufficient evidence to establish a time relationship between improved HH practices and a reduction in the incidence of NIs,13,14 in routine clinical practice adequate compliance with the established HH recommendations remains low and rarely exceeds 40–50%, even under study conditions.11,15–17 The strategies used to improve HH compliance include educational programs targeted to healthcare workers, modifications in the equipment used for such hygiene, and social pressure exerted by patients and their families upon healthcare workers–demanding compliance with the measures of asepsis.18–20

The introduction of alcohol derivatives has been shown to significantly improve the HH compliance rates, by allowing faster and safer disinfection of the hands.20–23

Taking into account the above, and considering the importance of NIs in the ICU and the benefits of HH compliance among healthcare workers in preventing such infections, the present study was designed to evaluate HH compliance among the ICU healthcare personnel in a phase prior to (P1) and after (P2) the introduction of an intervention program associated to the supply of an alcoholic solution for HH, and to analyze the factors independently associated to compliance with such recommendations, both before and after contact with the patient.

Subjects and methodAn interventional or quasi-experimental before–after study without a control group was designed, evaluating the situation before and after the intervention described below.

Study settingThe study setting comprised the ICU of a second level hospital center (Santa María del Rosell Hospital in Cartagena, Murcia, Spain). The medical team consists of a Head of Unit, a Section Chief, 12 intensivists, 5 residents in training in Intensive Care, and a variable number of residents in other specialties undergoing rotation training in the ICU. The rest of the non-medical personnel include 63 workers (35 nurses and 28 nursing auxiliary personnel members with fixed assignment to the ICU) and orderlies not specifically ascribed to the ICU (i.e., pertaining to the general orderlies staff division), with distribution in shifts–each with 6 nurses, 4 nursing auxiliary personnel members and two orderlies. There were no modifications in the composition or distribution of the workers in the Unit during the study period.

The ICU facilities consist of a hospitalization zone with 16 individual rooms (13 of which are isolated), a room for reception and stabilization of the more seriously ill patients, and a treatment preparation room. There are two independent accesses to the hospitalization zone: one for the patients and the other for their families. In addition, there is a material storage area (two rooms adjacent to the hospitalization zone), an office area, meeting room and dressing area. The unit is equipped with the usual protocols for performing invasive techniques, and moreover has participated in the ENVIN-ICU program years before conduction of the present study.

Study periodThe study was carried out between 1 February and 31 July 2006. In the first two weeks and in the last two weeks of the study period, we conducted 50h of observation of the in-ICU patient care activities of the healthcare personnel. The periods of observation were distributed into 3-h sessions in morning shifts and 2-h sessions in the afternoon shifts. Potential study subjects were taken to be all healthcare workers of the Unit attending patients admitted to the ICU during the observation sessions. The results of the first observation phase were not made known to the ICU personnel. Observation was carried out independently before and after contact with the patient, and the personnel were not aware of being under observation.

The indications for HH, the use of masks and gloves, or the adoption of aseptic techniques (mask, gloves, gown and drapes), were based on the usual recommendations10 and were referred to before and after the patient care activities.

Washing of the hands is considered hygienic when made with water and detergent soap, and is considered disinfecting or “surgical” when performed with substances approved for the purpose (iodine solution or water-soluble alcohol gel). The assessed techniques and times were adjusted to the recommendations referred to the effect.10 The following situations and activities were considered adequate for HH: before and after contact with the skin of the patient; before and after handling intravenous devices or bladder or nasogastric catheters; before and after contact with wounds; before and after contact with mucosal membranes; before and after contact with body fluids; following the removal of gloves or other barriers; and after cleaning, removal of waste, etc.

When performing procedures involving obligate sterility,10 and in addition to disinfection of the hands before and after the procedure, it was considered necessary to wear a cap, mask, sterile gown and sterile gloves, and to use sterile material and a sterile intervention field (“aseptic technique”).

Contact with the patient respirator or with the bladder catheter or urine bag was included within the category of contact with patient mucosal membranes. For increased simplification and to facilitate observation of the HH practices, simple contact with the bed of the patient or with inanimate objects in the surroundings was not taken into consideration, in the absence of contact with the skin of the patient.

Risk activity in turn was taken to constitute direct contact with mucosal membranes, wounds, blood or other biological material of the patient.

Intervention program for promoting the use of barrier measuresThe following measures were adopted:

- (1)

Acquisition of a water–alcohol antiseptic to add to the already existing products for hand hygiene and disinfection. The dispensers of the new product were distributed in the vicinity of each of the rooms of the ICU, together with a pair of dispensers in each of the treatment preparation rooms.

- (2)

Informative sessions on the new water–alcohol antiseptic for HH, with indications and instructions for use.

- (3)

Distribution of informative notices on the recommendations referred to the use of barrier measures and instructions on correct HH (with water and antiseptic soap or water–alcohol antiseptics) in strategic areas of the ICU: nursing controls, medication preparation rooms, offices and meeting rooms.

Patient severity upon admission to the ICU was established according to the criteria of the United States Centers for Disease Control (CDC),24 based on 5 codes:

- -

Severity code 1 (CDC 1): postsurgical patients requiring routine postoperative monitoring but no intensive care.

- -

Severity code 2 (CDC 2): stable medical patients requiring continuous prophylactic monitoring but no intensive care.

- -

Severity code 3 (CDC 3): stable patients requiring intensive care.

- -

Severity code 4 (CDC 4): unstable patients requiring intensive care.

- -

Severity code 5 (CDC 5): unstable patients requiring intensive care, frequent re-evaluation and treatment adjustments.

There were no epidemics or outbreaks of multiresistant pathogens requiring a change in habits or procedures during the study periods.

Data processing and statistical analysisThe data collected with the different forms were entered on a Microsoft Excel 2000® spreadsheet for posterior analysis using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 15 for Microsoft Windows. A descriptive analysis was made of the observations referred to HH compliance. Qualitative variables were presented as percentages, while quantitative variables were expressed as the mean, standard deviation and range. The comparative analysis of the variables was carried out with the Student t-test in the case of quantitative variables, and applying the chi-squared test in the case of qualitative variables. Statistical significance was considered for p<0.05. Multivariate analysis in turn was performed using the stepwise binary logistic regression method to identify the factors independently correlated to compliance with the HH recommendations on the part of the healthcare workers in our ICU, before and after contact with the patient. The influencing or potentially influencing variables were entered in the multivariate analysis, with particular consideration of whether the fact that observation was made before or after the intervention program constituted an independent factor associated to HH compliance (both before and after contact with the patient).

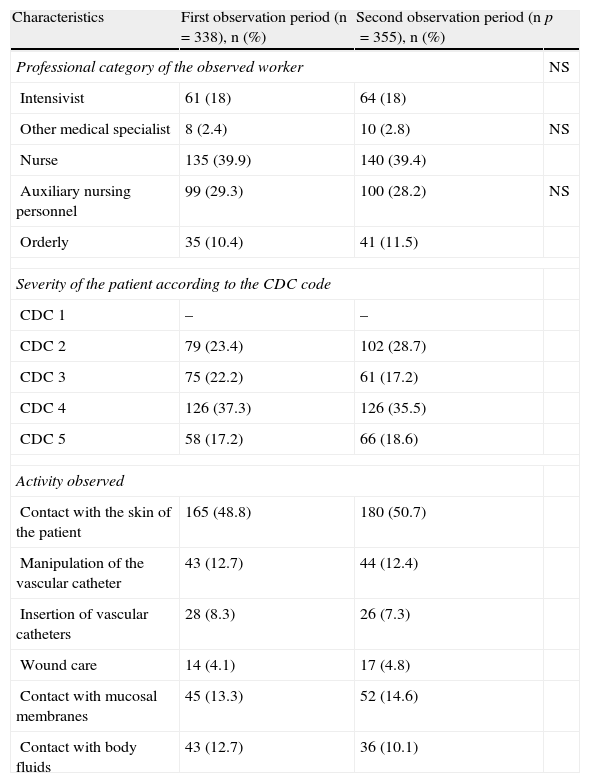

ResultsCompliance with the recommendations on the use of barrier measures at the start of the study (before the intervention program)We observed a total of 338 care activities in which HH compliance on the part of the intervening healthcare worker was assessed both before and after the care intervention. The categories of the observed workers, the patient severity according to the CDC code, and the different groups of activities observed during this period are shown in Table 1. Nurses were the most frequently observed professionals, while the patients most frequently implicated in the care activities corresponded to CDC severity code 4, and the most commonly observed care activity was simple contact with the skin of the patient.

Comparative analysis of the activities observed in both observation phases.

| Characteristics | First observation period (n=338), n (%) | Second observation period (n=355), n (%) | p |

| Professional category of the observed worker | NS | ||

| Intensivist | 61 (18) | 64 (18) | |

| Other medical specialist | 8 (2.4) | 10 (2.8) | NS |

| Nurse | 135 (39.9) | 140 (39.4) | |

| Auxiliary nursing personnel | 99 (29.3) | 100 (28.2) | NS |

| Orderly | 35 (10.4) | 41 (11.5) | |

| Severity of the patient according to the CDC code | |||

| CDC 1 | – | – | |

| CDC 2 | 79 (23.4) | 102 (28.7) | |

| CDC 3 | 75 (22.2) | 61 (17.2) | |

| CDC 4 | 126 (37.3) | 126 (35.5) | |

| CDC 5 | 58 (17.2) | 66 (18.6) | |

| Activity observed | |||

| Contact with the skin of the patient | 165 (48.8) | 180 (50.7) | |

| Manipulation of the vascular catheter | 43 (12.7) | 44 (12.4) | |

| Insertion of vascular catheters | 28 (8.3) | 26 (7.3) | |

| Wound care | 14 (4.1) | 17 (4.8) | |

| Contact with mucosal membranes | 45 (13.3) | 52 (14.6) | |

| Contact with body fluids | 43 (12.7) | 36 (10.1) | |

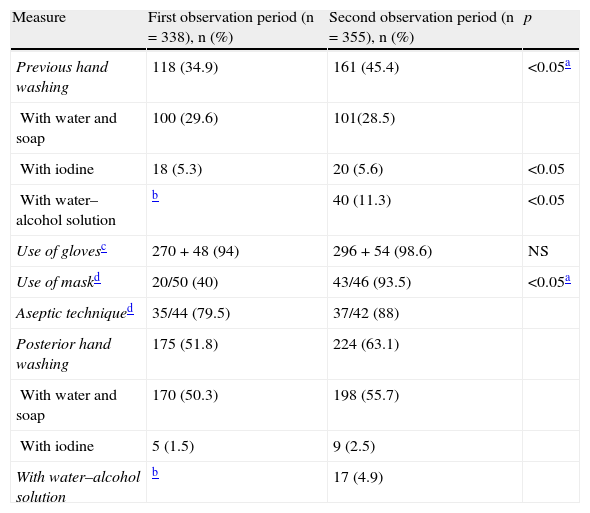

Among the 338 observations prior to patient care or contact, HH was performed in 118 cases (34.9%); of these, 100 (84.7%) corresponded to hygienic washing and the rest (18 cases) to surgical or disinfectant washing with iodine solution. In the 338 observations after contact with the patient, HH was performed in 175 cases (51.8%), of which 170 (97%) corresponded to simple hygienic washing. In 44 (13%) of these 338 observed activities a completely aseptic technique was required, but was only performed in 35 cases (79.5%). Gloves were worn during contact with the patient in 94.1% of the cases, and a surgical mask in 5.9% (Table 2).

Comparative analysis of the use of the different hygiene measures in the two observation phases.

| Measure | First observation period (n=338), n (%) | Second observation period (n=355), n (%) | p |

| Previous hand washing | 118 (34.9) | 161 (45.4) | <0.05a |

| With water and soap | 100 (29.6) | 101(28.5) | |

| With iodine | 18 (5.3) | 20 (5.6) | <0.05 |

| With water–alcohol solution | b | 40 (11.3) | <0.05 |

| Use of glovesc | 270+48 (94) | 296+54 (98.6) | NS |

| Use of maskd | 20/50 (40) | 43/46 (93.5) | <0.05a |

| Aseptic techniqued | 35/44 (79.5) | 37/42 (88) | |

| Posterior hand washing | 175 (51.8) | 224 (63.1) | |

| With water and soap | 170 (50.3) | 198 (55.7) | |

| With iodine | 5 (1.5) | 9 (2.5) | |

| With water–alcohol solution | b | 17 (4.9) |

Comparison between total hand washing acts before or after contact with the patient.

Not available in this phase of the study.

Gloves were used in 270+48=318 and in 296+54=350 of the 338 observations (nonsterile gloves+sterile gloves).

Performed/required; the value in parentheses refers to the % of the total of cases in which the aseptic technique or mask wearing proved necessary and was carried out.

Hand hygiene, before and after patient care, and the wearing of a mask and gloves, proved more frequent during the second observation period (Table 2). Of the 355 observations prior to patient care or contact, HH was carried out in 161 cases (65.4%); of these activities of hygiene, 101 (62.7%) corresponded to hygienic washing, 40 (24.8%) involved use of the alcohol gel product, and 20 (12.4%) involved the use of iodine. In the 355 observations posterior to contact with the patient, HH was performed in 224 cases (63.1%), of which 198 (81.1%) represented simple hygienic washing and only 17 (7.6%) involved use of the alcohol gel product. A completely aseptic technique was required in 42 of the 355 observed activities (11.8%) but was only performed in 37 cases (88.1%) (Table 2).

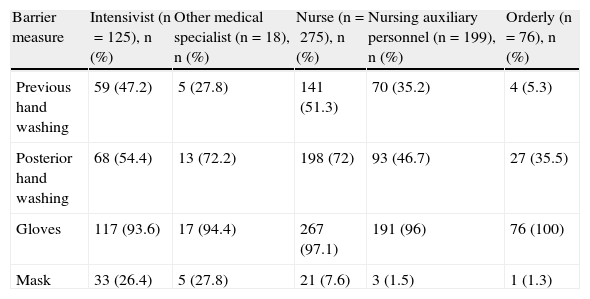

Factors related to hand hygiene complianceThe relationship between use of the barrier measures during patient care and the professional category of the intervening healthcare worker is reflected in Table 3. The association between HH compliance and patient severity and the type of activity carried out is in turn reflected in Table 4.

Use of hygiene measures according to professional category (includes all the observations made in both study periods).

| Barrier measure | Intensivist (n=125), n (%) | Other medical specialist (n=18), n (%) | Nurse (n=275), n (%) | Nursing auxiliary personnel (n=199), n (%) | Orderly (n=76), n (%) |

| Previous hand washing | 59 (47.2) | 5 (27.8) | 141 (51.3) | 70 (35.2) | 4 (5.3) |

| Posterior hand washing | 68 (54.4) | 13 (72.2) | 198 (72) | 93 (46.7) | 27 (35.5) |

| Gloves | 117 (93.6) | 17 (94.4) | 267 (97.1) | 191 (96) | 76 (100) |

| Mask | 33 (26.4) | 5 (27.8) | 21 (7.6) | 3 (1.5) | 1 (1.3) |

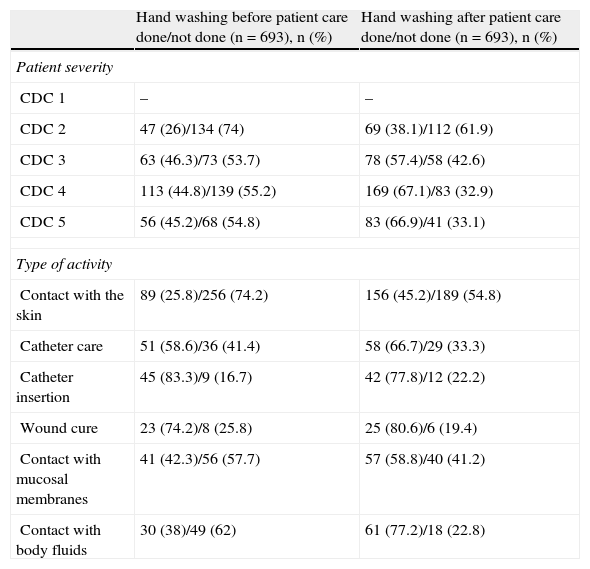

Hand washing before/after patient care according to the severity of the patient and the type of activity.

| Hand washing before patient care done/not done (n=693), n (%) | Hand washing after patient care done/not done (n=693), n (%) | |

| Patient severity | ||

| CDC 1 | – | – |

| CDC 2 | 47 (26)/134 (74) | 69 (38.1)/112 (61.9) |

| CDC 3 | 63 (46.3)/73 (53.7) | 78 (57.4)/58 (42.6) |

| CDC 4 | 113 (44.8)/139 (55.2) | 169 (67.1)/83 (32.9) |

| CDC 5 | 56 (45.2)/68 (54.8) | 83 (66.9)/41 (33.1) |

| Type of activity | ||

| Contact with the skin | 89 (25.8)/256 (74.2) | 156 (45.2)/189 (54.8) |

| Catheter care | 51 (58.6)/36 (41.4) | 58 (66.7)/29 (33.3) |

| Catheter insertion | 45 (83.3)/9 (16.7) | 42 (77.8)/12 (22.2) |

| Wound cure | 23 (74.2)/8 (25.8) | 25 (80.6)/6 (19.4) |

| Contact with mucosal membranes | 41 (42.3)/56 (57.7) | 57 (58.8)/40 (41.2) |

| Contact with body fluids | 30 (38)/49 (62) | 61 (77.2)/18 (22.8) |

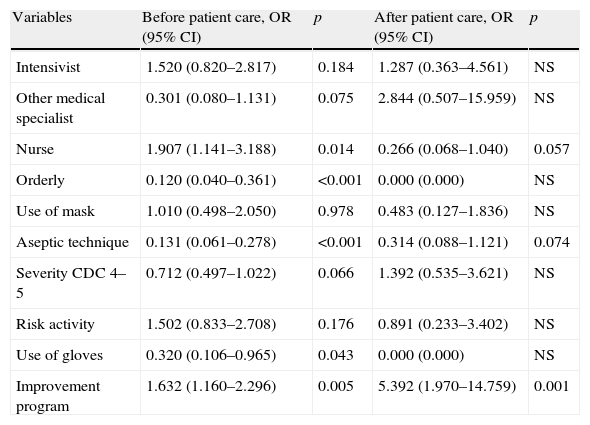

The multivariate analysis was performed to identify the factors independently that were related to HH compliance prior to contact with the patient, and which included 693 observations made before patient contact (338+355), the professional category “nurse” and the presence of a program for improvement in the use of barrier measures were associated to HH compliance before contact with the patient, while the wearing of gloves, the application of an aseptic technique and the professional category “orderly” were associated to failure to comply with hand hygiene before contact with the patient. In the multivariate analysis designed to identify the factors related to HH compliance after contact with the patient (and which likewise comprised 693 observations made after contact with the patient), only the presence of a program for improvement in the use of barrier measures was found to be significantly correlated to HH compliance (Table 5).

Hand washing exposure factors.a

| Variables | Before patient care, OR (95% CI) | p | After patient care, OR (95% CI) | p |

| Intensivist | 1.520 (0.820–2.817) | 0.184 | 1.287 (0.363–4.561) | NS |

| Other medical specialist | 0.301 (0.080–1.131) | 0.075 | 2.844 (0.507–15.959) | NS |

| Nurse | 1.907 (1.141–3.188) | 0.014 | 0.266 (0.068–1.040) | 0.057 |

| Orderly | 0.120 (0.040–0.361) | <0.001 | 0.000 (0.000) | NS |

| Use of mask | 1.010 (0.498–2.050) | 0.978 | 0.483 (0.127–1.836) | NS |

| Aseptic technique | 0.131 (0.061–0.278) | <0.001 | 0.314 (0.088–1.121) | 0.074 |

| Severity CDC 4–5 | 0.712 (0.497–1.022) | 0.066 | 1.392 (0.535–3.621) | NS |

| Risk activity | 1.502 (0.833–2.708) | 0.176 | 0.891 (0.233–3.402) | NS |

| Use of gloves | 0.320 (0.106–0.965) | 0.043 | 0.000 (0.000) | NS |

| Improvement program | 1.632 (1.160–2.296) | 0.005 | 5.392 (1.970–14.759) | 0.001 |

OR<1 implies a lesser probability of having washed hands, and OR>1 implies a greater probability of having washed hands.

Includes all the observations, corresponding to the first and second observation period, total=693.

The hand hygiene (HH) compliance rate (considering both hygienic washing with water and soap and disinfection with iodine or alcohol gel) as observed in our study in the first observation of patient care (35% before contact with the patient and 52% after contact) was similar to that reported by other authors,17 with rates usually under 50%.

Following application of the intervention program to promote the use of barrier measures, the frequency of HH compliance increased significantly both before and after patient care activities (45% and 63% before and after contact with the patient, respectively), in coincidence with the observations of previous studies.17,25 However, it must be noted that although HH compliance increased in relation to patient care, and did so as a result of the introduction of hand washing with alcohol-based solutions, a very important percentage of hand washing continued to involve water and soap (hygienic washing), when the actual recommendation was disinfection of the hands with water–alcohol antiseptic formulations.10 It is therefore clear that implementation of the program was unable to sufficiently underscore this recommendation, which is currently regarded as the gold standard for HH, probably because only informative notices were distributed, with no other more detailed and continued training activities other than mention of the fact that alcoholic solution dispensers were going to be acquired.

The publication of HH guides approved by renowned international organisms does not ensure HH compliance,26 and interventional programs must be introduced to promote adequate use.27 In this context, the introduction in our ICU of a training program was independently associated to HH compliance, though it would have been advisable to reach water–alcohol antiseptic solution based hand disinfection rates of close to 30–40%.18,20,22,23 The intervention in our study was not sufficiently comprehensive or sustained over time to allow the drawing of conclusions regarding the performance or yield of training programs addressing HH or other barrier measures.

In our study, the bivariate analysis showed activities targeted to less seriously ill patients (as determined by the CDC severity coding system), as well as simple contact with the skin of the patient, to be associated to lower HH compliance rates–possibly because such activities are believed to involve a lesser risk of contamination of the hands. Moreover, the prevalence of HH compliance before patient care was lower than after patient care. This may be explained by healthcare worker perception of the risk of personal contamination secondary to contact with the patient, with lesser concern about the possible risk of personally representing a vector for the transmission of pathogenic organisms to other people.17,25,27 Independent of the fact that there may be activities with increased contamination of the hands, including respiratory care, diaper changes, contact with body secretions, etc., contamination of the hands can also occur even after contact with inanimate objects in the vicinity of the patient. However, it is also common to only perceive the potential risk of cross-transmission after coming into contact with the patient, or to be only concerned about personal protection.27,28 As has been mentioned, these opportunities for adequate HH (coming into contact with inanimate objects in the vicinity of the patient) were not taken into consideration in our observational survey–a fact that constitutes a limitation of the study.

In coincidence with other studies,17,27 increased HH compliance (both before and after patient care) was observed among the nursing personnel (compared with the rest of healthcare workers)–though belonging to this professional category was only identified as being independently associated to HH before patient care, and not after patient care. In contrast, orderlies were found to pose a greater risk of failure to comply with HH before patient contact–possibly because their more limited training made them less aware of the risk of germ transmission. In this sense, educational interventions probably should place greater emphasis on this professional category. Of note is the fact that there were no modifications during our periods of evaluation in the composition or distribution of the ICU workers–a situation that is not usually seen in clinical practice or in longer lasting studies.

The wearing of gloves did not show differences among the professional categories, reaching prevalence of over 90%. This might explain why the wearing of gloves was also identified as a risk factor for failure to comply with HH, as has been already documented elswehere.13 The fact of coming into contact with the patient through an aseptic technique was paradoxically associated to a lesser probability of HH compliance, i.e., the observed personnel correctly adopted all the measures of the aseptic technique (gown, mask, etc.), but failed to wash their hands. Similar findings were made after contact with the patient, though statistical significance was not reached.

Among the limitations of our study, mention must also be made of the fact that the duration of observation was only 50h in each period; as a result, the number of opportunities for assessing compliance with the recommendations on HH was lower than in other studies (a total of 693 occasions). Moreover, feeling observed may have modified worker behavior, causing us to overestimate the frequency of HH compliance–though other authors have reported no differences on comparing the results of overt observation versus more discrete observation.

In conclusion, our study shows that before introduction of the educational intervention, HH compliance prior to patient care was less frequent than after patient care, and that in most cases hygienic washing rather than disinfectant or surgical washing was involved, both before and after providing patient care. In contrast, after applying the educational intervention, HH compliance was more frequent than in the initial study period–though without changes in the technique used, i.e., the healthcare workers continued to incorrectly wash their hands with soap and water rather than using an antiseptic solution. Observation after the intervention program was independently associated in the multivariate analysis to HH compliance both before and after coming into contact with the patient. However, in our ICU it is necessary to adopt further measures to improve HH compliance involving the use of an adequate technique (antiseptic washing).

Please cite this article as: García-Vázquez E, et al. Influencia de un programa de intervención múltiple en el cumplimiento de la higiene de manos en una unidad de cuidados intensivos. Med Intensiva. 2012;36:69–76.