Burn patients are complex patients, but the therapeutic advances made over the last few years have reduced morbimortality. However, in the presence of inhalation injuries, the reduction of mortality is not so significant.1

One of the main problems with patients with inhalation injuries is diagnosing them. The traditional signs of inhalation have proven insufficient yet despite the introduction of fibrobronchoscopy for confirmatory diagnosis. To this day there is still no consensus on which should be the diagnostic method of choice.2 Similarly, there is no such a thing as a widely accepted classification on the different degrees of inhalation or severity scores with prognostic value.

The usual hemodynamic complexity of burn patients is greater in this type of patients. Inhalation syndrome not only affects breathing but also increases inflammatory response at systemic level leading to increased hemodynamic alteration in the initial resuscitation phase. Traditionally, patients with inhalation injuries often require larger volumes of fluids during this phase. Added to other complications associated with the intubation and the ventilator this may be responsible for the higher morbimortality of these patients.

However, most studies have been conducted without advanced hemodynamic monitoring or without discriminating patients with and without mechanical ventilation. In this sense, the ATLS recommendation on the intubation and mechanical ventilation of patients with suspected inhalation initially reduced mortality in these patients, especially where the accident took place. Nevertheless, mechanical ventilation is no stranger to complications and causes hemodynamics changes. This is critical in burn patients with low intravascular volume since it reduces the venous return and cardiac output. This demands more fluid supply which can be harmful in the mid-term.3 The ventilation creep phenomenon has been used to refer to the tendency of early intubation of patients with suspected inhalation when, in some cases, inhalation was not even confirmed in the first place.4 Cancio et al.5 studied the association between fluid therapy and mortality and concluded that mechanical ventilation—not inhalation—is associated with the larger volume of fluids supplied during the resuscitation phase. Other authors claim that mechanical ventilation—not damage to the airway induced by smoke inhalation—is associated with mortality in burn patients.6

The airways of patients with inhalation injuries are potentially difficult due to the direct action of temperature and irritation from toxic fumes following the edema originated during the initial resuscitation phase. That is why the initial and prophylactic intubation is recommended in patients with suspected inhalation.7 However, the right prognosis and stratification of inhalation could avoid problems associated with mechanical ventilation.

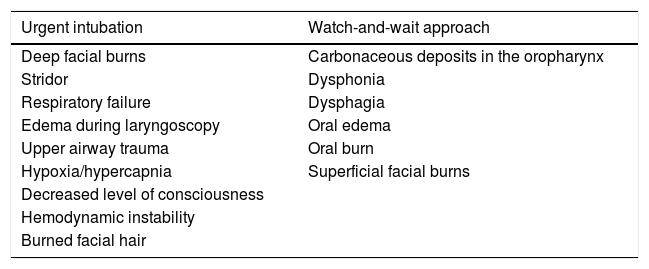

Recently, some authors have proposed the Denver criteria8 for the intubation of patients with suspected inhalation. These criteria have greater sensitivity compared to the classic criteria and to ABA recommended criteria because they add 2 new criteria to the latter. They recommend a watch-and-wait approach in patients with carbonaceous deposits in the oropharynx, dysphonia, dysphagia, oral edema, oral burns or superficial facial burns (Table 1).

Criteria for intubation.

| Urgent intubation | Watch-and-wait approach |

|---|---|

| Deep facial burns | Carbonaceous deposits in the oropharynx |

| Stridor | Dysphonia |

| Respiratory failure | Dysphagia |

| Edema during laryngoscopy | Oral edema |

| Upper airway trauma | Oral burn |

| Hypoxia/hypercapnia | Superficial facial burns |

| Decreased level of consciousness | |

| Hemodynamic instability | |

| Burned facial hair |

Based on the Denver criteria and ABA/2011.

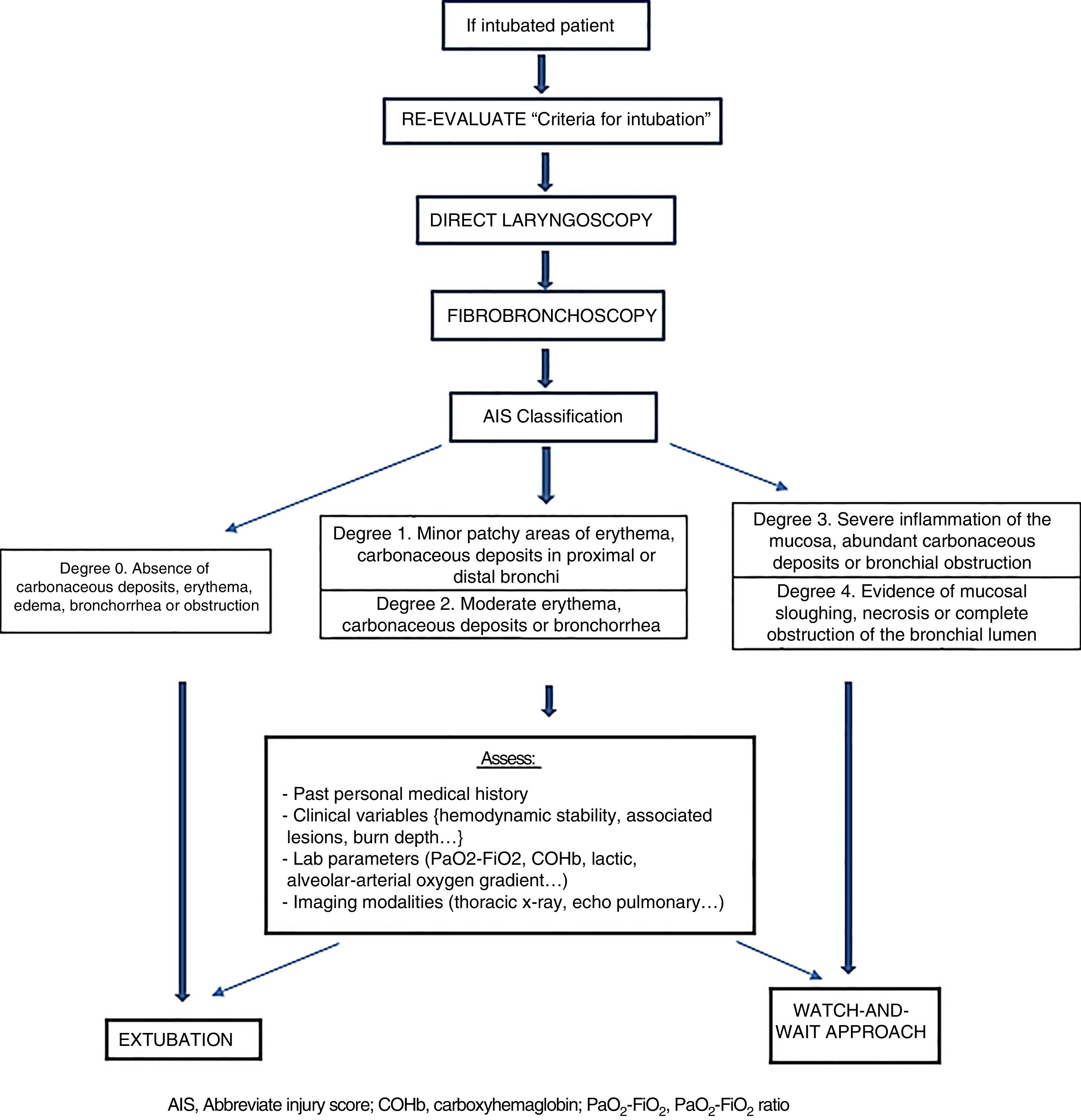

On top of detecting the presence of inhalation, we need to stratify the degree of inhalation for treatment and prognostic purposes. Nowadays, the most widely used and accurate diagnostic method is fibrobronchoscopy, but there are no prognostic scores. Endorf and Gamelli proposed the Abbreviated Injury Score for the stratification of injuries based on fibrobronchoscopy findings,9 being 0 the absence of mucosal injuries and carbonaceous deposits and 4 the necrosis of the mucosa. They found no differences in the volume of fluids supplied among the different degrees of inhalation. Also, even though they saw that groups 3 and 4 had worse prognosis, individually they were not representative of the prognostic value of each degree. Therefore, Aung et al.10 classified the injury scoring system of the Abbreviated Injury Score into 3 groups (medium, moderate, and severe), and saw that this classification had a better prognostic correlation being the mortality of patients classified as severe clearly higher.

In our own opinion, this classification can also be useful to assess early extubations in intubated patients who do not meet the moderate or severe group criteria. In patients categorized as patients with moderate inhalation, clinical and lab criteria may be used to assess extubation, since this group is associated with more days on mechanical ventilation, but not a higher mortality rate. These parameters may be those that have proven to have prognostic value like the PaO2-FiO2 ratio, the alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient or carboxyhemoglobin. Extra-hospital EMS should be in charge of determining the carboxyhemoglobin levels due to its short half-life and its fast normalization with high FiO2.

In our own experience,11 patients with inhalation injuries show no differences in fluid supply during initial resuscitation compared to patients without inhalation injuries. However, mechanical ventilation is associated with a higher fluid supply and a higher mortality rate.

The importance we attribute to mechanical ventilation is consistent with the importance attributed by other authors.12 Therefore, based on our own experience and the medical literature we should focus on achieving a correct diagnosis in patients with inhalation injuries. The Denver criteria can be useful to avoid unnecessary intubations. In patients already intubated on arrival at the Burn Center, a new laryngoscopy should be performed to assess the patency of the upper airway followed by a fibrobronchoscopy to stratify the degree of inhalation according to the Abbreviated Injury Score. In patients who do not meet severity criteria in the fibrobronchoscopy and without compromised upper airways, early extubations can be considered as long as other clinical, analytical and radiologic criteria are observed (Fig. 1). We strongly believe that by using this protocol we can reduce mechanical ventilation-induced morbimortality in patients with inhalation injuries.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

Please cite this article as: Cachafeiro Fuciños L, Sánchez Sánchez M, García de Lorenzo y Mateos A. Ventilación mecánica en el paciente quemado crítico con inhalación: ¿podemos evitarla? Med Intensiva. 2020;44:54–56.