Although we have always been aware of the long way lying ahead after patient admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), only recently has research highlighted the long-term suffering and devastating consequences which the disease condition can generate in critical patients and their families. This has led the international societies of Intensive Care Medicine to define the so-called post-intensive care syndrome (PICS) and post-intensive care syndrome - family (PICS-F).1–5

We have the responsibility of favoring continuous patient and family care outside the hospital setting, sharing our professional experience and the available necessary resources. Collaboration with the professionals at different levels of healthcare can allow early identification and management of the consequences of this clinical scenario.

Given the growing importance of PICS and PICS-F, the “PICS protocol” was developed following a multidisciplinary meeting with the participation of different hospital (Intensive Care Medicine, Physical Medicine, Ear, Nose and Throat, Psychiatry and Continuous Nursing Care) and out-hospital Departments (Family and Community Care Medicine).

The “PICS protocol” was implemented in June 2018 with the aim of identifying patients at risk of suffering PICS, and of applying the measures needed to ensure the prevention or early treatment of the syndrome while also exploring the effectiveness of the adopted measures (in the ICU, hospital ward and home). A secondary objective was to facilitate follow-up and improve the quality of life of the patients and their families.

The protocol begins with the planning of patient discharge from the ICU through the activation of a Continuous Nursing Care Team (CNCT). Once in the hospital ward, the patient is monitored by the Department of Intensive Care Medicine (for as long as required by the patient, and as previously agreed upon), with closer monitoring by the CNCT (in charge of coordination of the professionals, Departments and material resources needed during patient and family stay in the ward). The CNCT in turn supervises a family/caregiver support program and plans hospital discharge with the corresponding healthcare level, guaranteeing the continuity of care and contacting the Primary Care Nursing Team (which becomes in charge of follow-up once the patient has been discharged home).

A total of 47 patients were recruited between June 2018 and June 2019. The inclusion criteria were: development of delirium, acquired muscle weakness or swallowing problems during admission to the ICU, or any patient admitted to the ICU for over 7 days. The exclusion criteria comprised: patient age under 18 years, limitation of life support and a history of psychiatric disease or dementia.

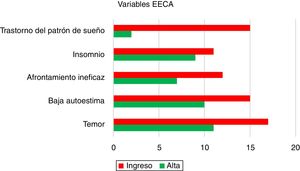

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample are described in Table 1. At both admission to the hospital ward and at discharge home, the CNCT assessed 5 items: fear, low self-esteem, ineffective coping, insomnia and sleep disorders. The data collected are shown in Fig. 1. The Barthel score evidenced improvement of the degree of dependency, with a score of 45 upon admission (interquartile range [IQR] 35–65) versus 65 at discharge (IQR 40–92.5). The Zarit scale (which assess caregiver burden) at discharge yielded a score of <17 (low burden in relation to care giving tasks) in 97.6% of the cases.

Demographic characteristics.

| All patients (n = 47) | |

|---|---|

| Age (median, IQR) | 69 (63−77) |

| Gender (number, %) | |

| Male | 29 (61.7) |

| Female | 18 (38.3) |

| Location prior to admission to ICU (number, %) | |

| Emergency/observation | 19 (40.4) |

| Hospital ward | 12 (25.5) |

| Operating room/resuscitation | 16 (34) |

| Type of patient (number, %) | |

| Medical | 33 (70.2) |

| Surgical (urgent) | 5 (10.6) |

| Surgical (elective) | 9 (19.1) |

| Reason for admission to ICU (number, %) | |

| Sepsis | 15 (31.9) |

| Respiratory failure | 15 (31.9) |

| Postsurgery | 9 (19.1) |

| Others | 8 (17) |

| Comorbidities (number, %) | |

| Cardiovascular | 33 (70.2) |

| Respiratory | 21 (44.7) |

| Renal | 9 (19.1) |

| Hematological malignancies | 10 (21.3) |

| Endocrine | 26 (55.3) |

| Hepatic | 7 (14.9) |

| Severity scores (median, IQR) | |

| SAPS3 | 60 (51−68) |

| Frailty (CFS) | 3 (2−7) |

| SOFA upon admission | 4 (2−8) |

| Days in hospital prior to admission to ICU (median, IQR) | 0 (0−3) |

| Stay in ICU (median, IQR) | 9 (4−16) |

| Stay in hospital ward at discharge from ICU (mean, SD) | 21.9 (±19.5) |

| Survival at discharge from ICU (number, %) | 47 (100) |

| Survival at discharge from hospital (number, %) | 43 (91.5) |

| Organ failure (number, %) | |

| Cardiovascular | 35 (74.5) |

| Respiratory | 40 (85.1) |

| Renal | 28 (59.6) |

| Hepatic | 5 (10.6) |

| Hematological | 10 (21.3) |

| Neurological | 17 (36.2) |

| Number of organ failures per patient (median, IQR) | 3 (2−4) |

| Supportive measures | |

| Mechanical ventilation (number, %) | 32 (68.1) |

| Days on MV (median, IQR) | 8.5 (4.5−14.25) |

| Prone decubitus (number, %) | 3 (6.4) |

| Continuous NM relaxation (number, %) | 3 (6.4) |

| Tracheotomy (number, %) | 3 (6.4) |

| RRT (number, %) | 3 (6.4) |

| Parenteral nutrition (number, %) | 12 (25.5) |

| Complications during admission to ICU (number, %) | |

| Muscle weakness | 17 (36.2) |

| Nutritional risk | 22 (46.8) |

| Delirium | 17 (36.2) |

| Isolation at discharge from ICU (number, %) | |

| Preventive | 16 (34) |

| Confirmed | 7 (14.9) |

IQR: interquartile range. %: percentage. ICU: Intensive Care Unit. CFS: Clinical Frailty Scale. MV: mechanical ventilation. NM: neuromuscular. RRT: renal replacement therapy.

We analyzed the possible associations between the variables recorded by the CNCT and the medical complications observed in the ICU. Linear logistic regression analysis showed that those patients who suffered delirium and neurological failure during admission to the ICU had a greater incidence of low self-esteem (p = 0.016) and fear (p = 0.013). Sleep disorders (sleep pattern disturbances and insomnia) were mainly associated to respiratory failure (p = 0.002) and nutritional risk (p = 0.040). No differences were recorded between the severity scales and the Barthel scale at either admission or discharge. Lastly, statistically significant associations were observed between a greater number of days of ICU stay and sleep pattern disturbances (p < 0.001) and fear (p = 0.018), and between the days of stay in the hospital ward and ineffective coping (p = 0.037), insomnia (p = 0.004) and fear (p = 0.01).

One year after introduction of the protocol, we found that early intervention on the part of a multidisciplinary team improved several mental health components (fear, self-esteem, coping and sleep disorders) and the patient capacity to perform basic activities of daily living (as evaluated by the Barthel scale). The positive outcomes obtained with the Zarit scale (caregiver burden) would also be a consequence of the great support perceived by the patient families and related persons.

Post-intensive care syndrome has a strong impact upon critical patient health, implying frequent readmissions and an increased consumption of resources. In recent years, different models for monitoring the critically ill at discharge from the ICU or hospital have been proposed.6 These models are suggested to offer a range of advantages: (a) the creation of a continuous care safety and coordination network; (b) the favoring of quality care focused on the patient and the family through information, communication and support; and (c) the improvement of quality of life of both the patients and their families, by reducing the number of readmissions, facilitating the recovery of autonomy and return to work, and recovering lost social life.7

However, randomized controlled trials have failed to yield the desired results. The clinical evidence published to date is neither homogeneous nor standardizable (level of evidence III). A systematic review carried out in 2018 on the impact of follow-up programs at discharge from the ICU8 suggested that there was not enough evidence to affirm that such programs are effective in identifying and addressing new deficiencies in multiple domains referred to patient recovery.

The management of complex patients at risk of PICS requires a multidisciplinary approach both in and out of hospital. For many ICU survivors, discharge from hospital marks the beginning of an arduous struggle. Despite positive preliminary findings, it remains to be established whether our early intervention can confirm its results in a larger study cohort and, particularly, in relation to quality of life over the long term. There is still quite some way to go.

Publication ethicsThe study data were prospectively compiled from the registry of the ICU of Hospital Universitario del Henares (Madrid, Spain), with approval from the Ethics Committee of Universidad Francisco de Vitoria (Madrid, Spain), and after due obtainment of consent from the patients or families.

Contributions of the authorsAll the authors contributed to the study conception and design, and to data acquisition: D. Varillas-Delgado performed data analysis and interpretation. B. Lobo-Valbuena drafted the manuscript. Federico Gordo, M.D. Sánchez-Roca, M.P. Regalón-Martín and J. Torres-Morales performed critical review of the intellectual content. Federico Gordo and M.D. Sánchez-Roca approved the final version.

Financial supportThe present study received no financial support.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Lobo-Valbuena B, Sánchez Roca MD, Regalón Martín MP, Torres Morales J, Varillas Delgado D, Gordo F. Síndrome post-UCI: Amplio espacio de mejora. Análisis de los datos tras un año de implementación de protocolo para su prevención y manejo en un hospital de segundo nivel. Med Intensiva. 2021;45:e43–e46.