Chemokines are a large superfamily of small proteins that not only function in leukocyte trafficking, but are also necessary for linkage between innate and adaptive immunity. Little is known about their role in septic shock. We hypothesized that serum levels of the most important chemokines are related to organ failure, disease severity and outcome.

DesignA prospective observational study was carried out.

SettingSurgical-clinical Intensive Care Unit.

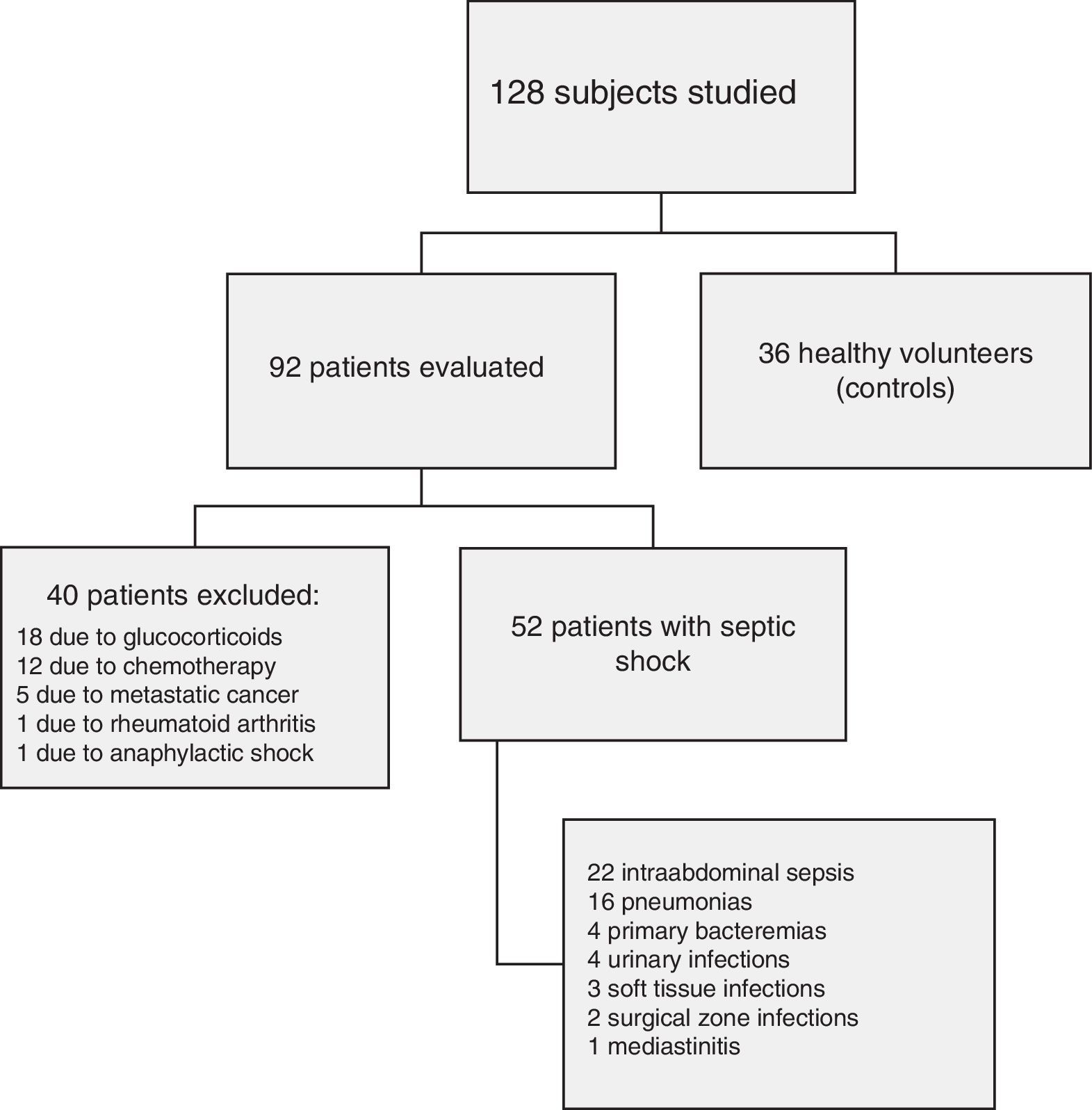

PatientsNinety-two patients diagnosed with septic shock using international criteria. Forty patients were excluded due to acquired immunity disturbances. Samples from 36 healthy controls were also analyzed.

InterventionsNone.

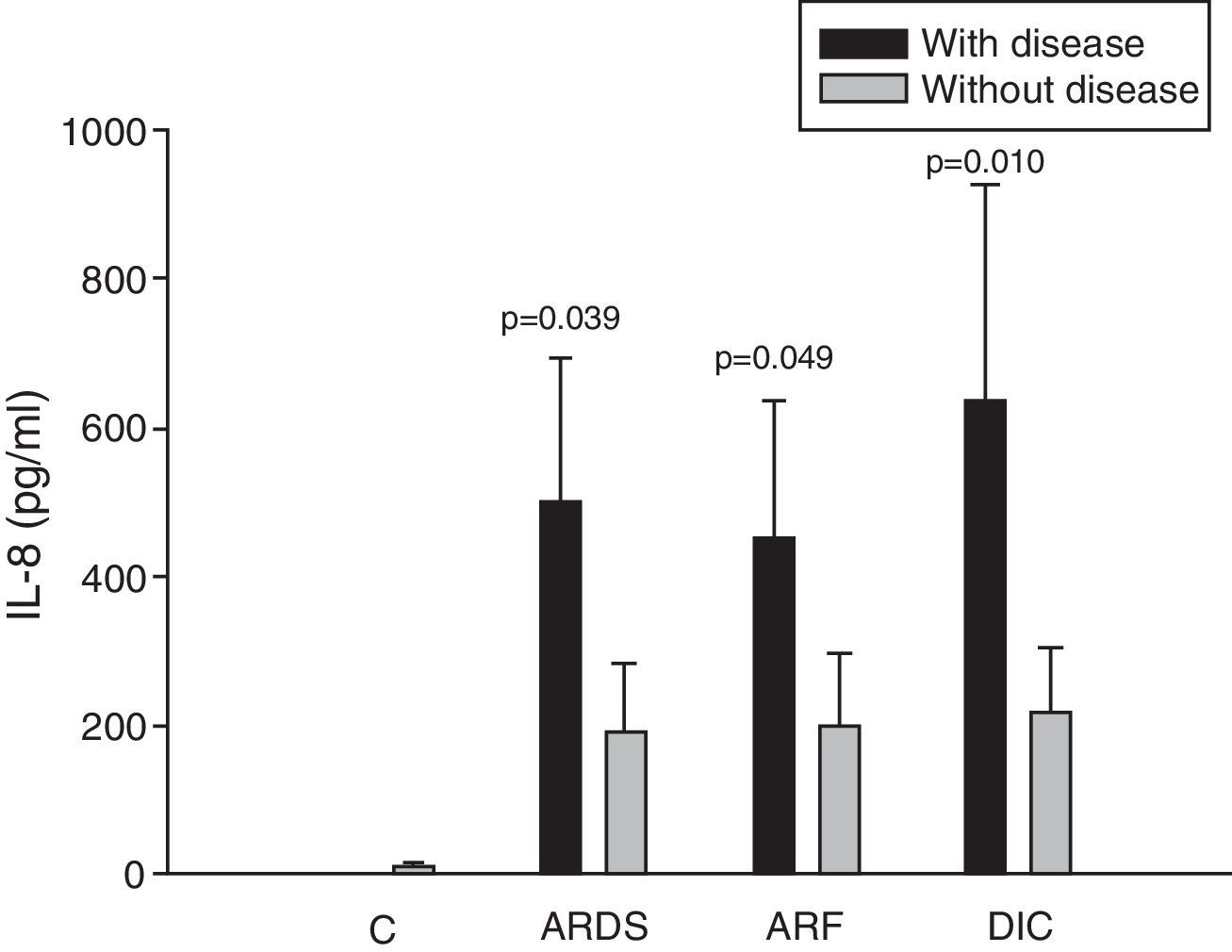

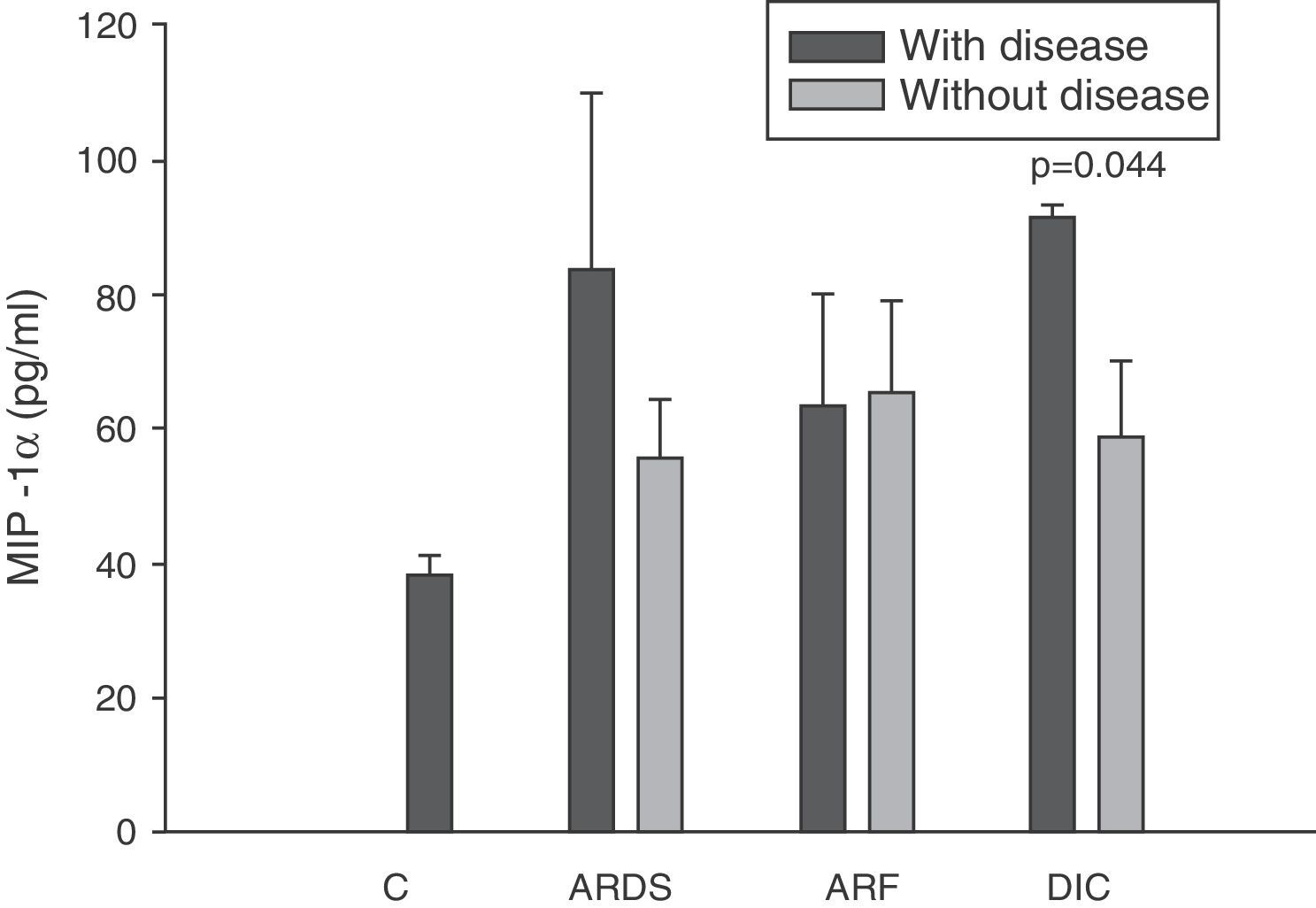

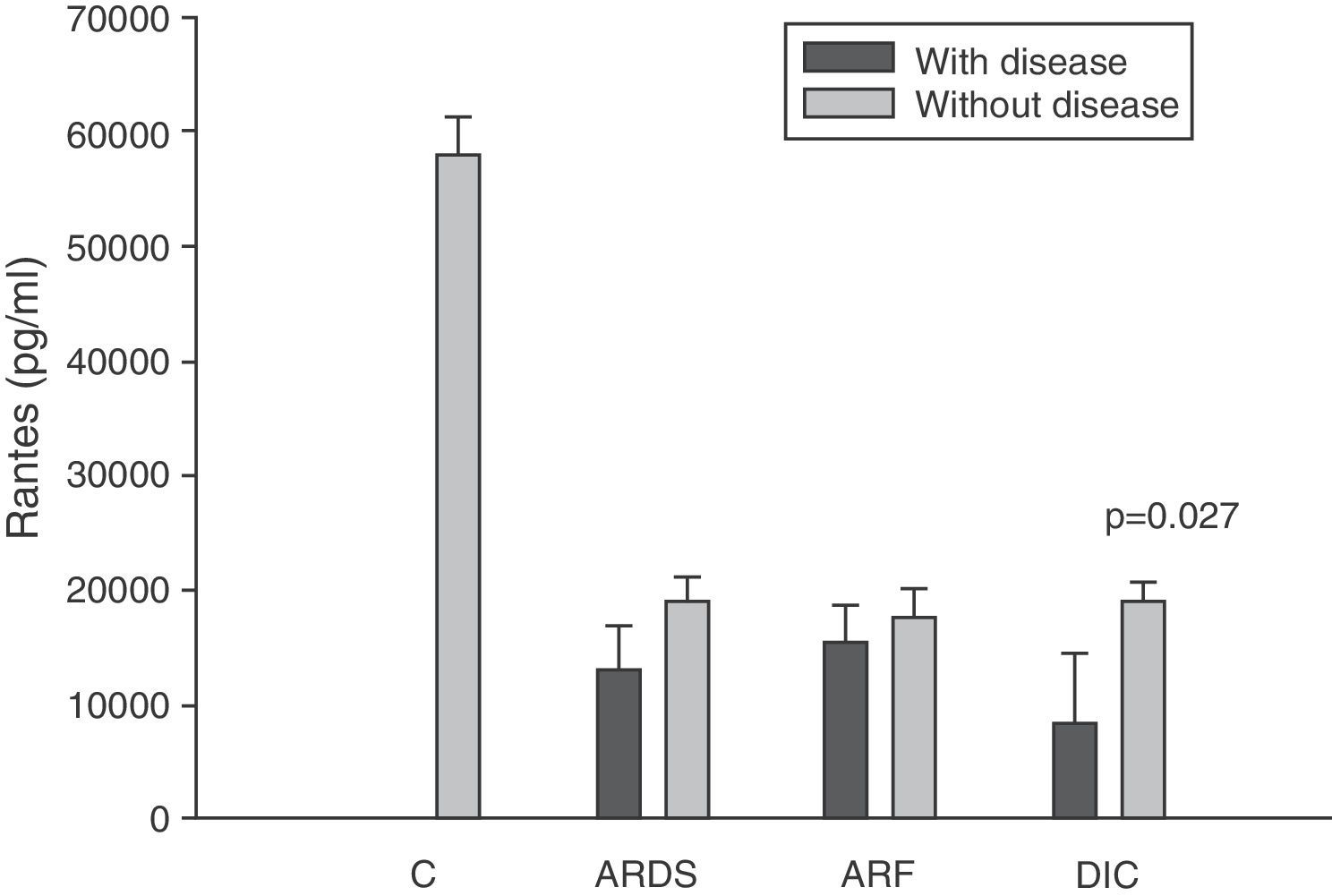

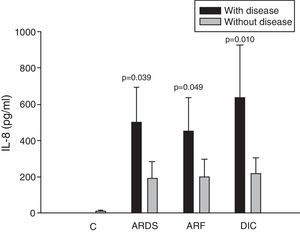

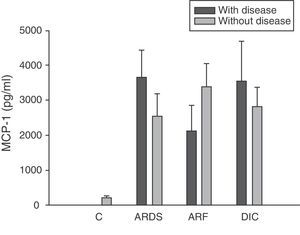

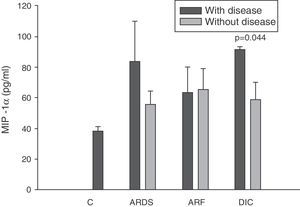

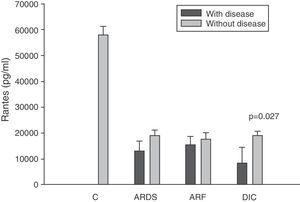

ResultsIn 46% of the patients who suffered acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), IL-8 levels were higher than in patients without ARDS (499.9±194.1 vs 190.8±91.7pg/ml; p=0.039). This molecule was also higher in 36% of the patients with sepsis-induced acute renal failure (ARF) (453.3±181.6 vs 201.3±95.9pg/ml; p=0.049). Coagulopathy was found in 19% of the septic shock patients with elevated serum IL-8 levels (635.8±292.3 vs 218.7±87.0pg/ml; p=0.010), elevated MIP-1α (91.4±27.3 vs 58.8±11.1pg/ml; p=0.044), and low circulating RANTES levels (8162.2±6321.0 vs 18781.8±11.1pg/ml; p=0.027). No significant differences were found between survivors and non-survivors at any time of follow-up.

ConclusionsUpon admission to the ICU, IL-8 is a reliable biomarker of sepsis-induced AFR, ARDS and coagulopathy. Altered circulating MIP-1α and RANTES levels are also found in patients with septic shock and coagulopathy. However, chemokines do not appear to be good biomarkers of mortality in septic shock.

Las quimioquinas son una gran familia de pequeños péptidos que tienen una participación clave no solo en el control del tráfico de los leucocitos, sino también se ha visto que son necesarios en las interacciones entre la inmunidad innata y adaptativa. El papel de estas moléculas es poco conocido en el seno del shock séptico. Nuestra hipótesis es que los niveles séricos de las principales quimioquinas tienen relación con los diferentes fallos orgánicos y con el pronóstico de los pacientes con shock séptico.

DiseñoEstudio prospectivo y observacional.

ÁmbitoUnidad de Cuidados Intensivos médico-quirúrgica.

PacientesNoventa y dos pacientes cumplieron criterios internacionales de shock séptico con demostración de una infección, de los que se excluyeron 40 por presentar diferentes alteraciones inmunitarias adquiridas. Treinta y seis voluntarios sanos sirvieron de grupo control.

IntervencionesNinguna.

ResultadosEl 46% de los pacientes presentaron síndrome de distrés respiratorio agudo (SDRA) y en ellos los niveles séricos de IL-8 se encontraban elevados (499,9±194,1 vs. 190,8±91,7pg/ml; p=0,039). Esta molécula también estaba elevada en el 36% de los pacientes con shock séptico que tenían fracaso renal agudo (FRA) (453,3±181,6 vs. 201,3±95,9pg/ml; p=0,049). El 19% de los pacientes presentaron coagulopatía y en ellos se observó una elevación de los niveles de IL-8 (635,8±292,3 vs. 218,7±87,0pg/ml; p=0,010), de MIP-1α (91,4±27,3 vs. 58,8±11,1pg/ml; p=0,044) y niveles bajos de RANTES (8162,2±6321,0 vs. 18781,8±11,1pg/ml; p=0,027). No encontramos diferencias significativas en los niveles séricos de quimioquinas estudiadas en pacientes con shock séptico entre los supervivientes y los que fallecieron.

ConclusionesAl ingreso en la UCI, la IL-8 es un buen biomarcador de FRA y de SDRA, así como de coagulopatía en pacientes con shock séptico. MIP-1α y RANTES también presentan niveles séricos alterados en la coagulopatía asociada a la sepsis. A pesar de esto, las quimioquinas no parecen ser buenos marcadores pronósticos en estos pacientes.

Multiorgan failure is the main cause of death in patients with sepsis.1 The prognosis of multiorgan dysfunction syndrome (MODS) is conditioned to the number of failed organs, the severity of failure, and its duration in time. In a study published by Knaus et al., the mortality rate was 22% among patients with single organ failure lasting less than 24h, but increased to 42% when the condition persisted for 7 days. In turn, the mortality rate was found to be 80% in the case of three or more failed organs with a duration of less than 24h, and reached 100% when the condition persisted for more than four days.2

Although severity scores have been developed to characterize the degree of multiorgan dysfunction and predict mortality among patients with sepsis, understanding the physiopathology of MODS represents an ongoing challenge.3 The development of MODS is a consequence of excessive activation of the inflammatory response. To date, however, the treatments that have attempted to counter this exaggerated systemic inflammatory response have failed.4 Furthermore, most patients who survive the initial aggression of sepsis die days or weeks later as a result of multiorgan failure and in a situation of immunosuppression.3

At cellular level, a number of mechanisms contribute to the development of MODS, including microvascular thrombosis, neutrophil-induced damage, bacterial translocation, cytokine release, endothelial dysfunction, cell apoptosis, etc.5 The chemokines constitute a large family of cytokines that stimulate the movement of leukocytes and regulate their migration from the bloodstream toward the tissues. They are regarded as proinflammatory cytokines, since they induce the production and release of histamine, enzymes and defensins. However, in contrast to other cytokines, the chemokines do not induce other cytokines or produce fever or acute phase reactants. Furthermore, chemokines in large circulating concentrations exert desensitizing effects and can suppress local inflammation.6

Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) plays a key role in the physiopathology of sepsis and septic shock. An increase in its activity has been associated with a higher mortality rate and a poorer prognosis.7 NF-κB mediates the transcription of a range of genes encoding for inflammatory molecules such as cytokines, adhesion molecules, enzymes, immune receptors, acute phase reactants and chemokines–including interleukin-8 (IL-8), macrophage inflammatory protein 1-α (MIP-1α), type 1 monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP-1) and RANTES (regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted) protein. The role of these chemokines when soluble in plasma in the development of organ dysfunction in patients with sepsis has not been well established to date.

The present study postulates that the plasma levels of these circulating chemokines are increased in patients with septic shock, and that this in turn contributes to the development of organ dysfunction and patient mortality.

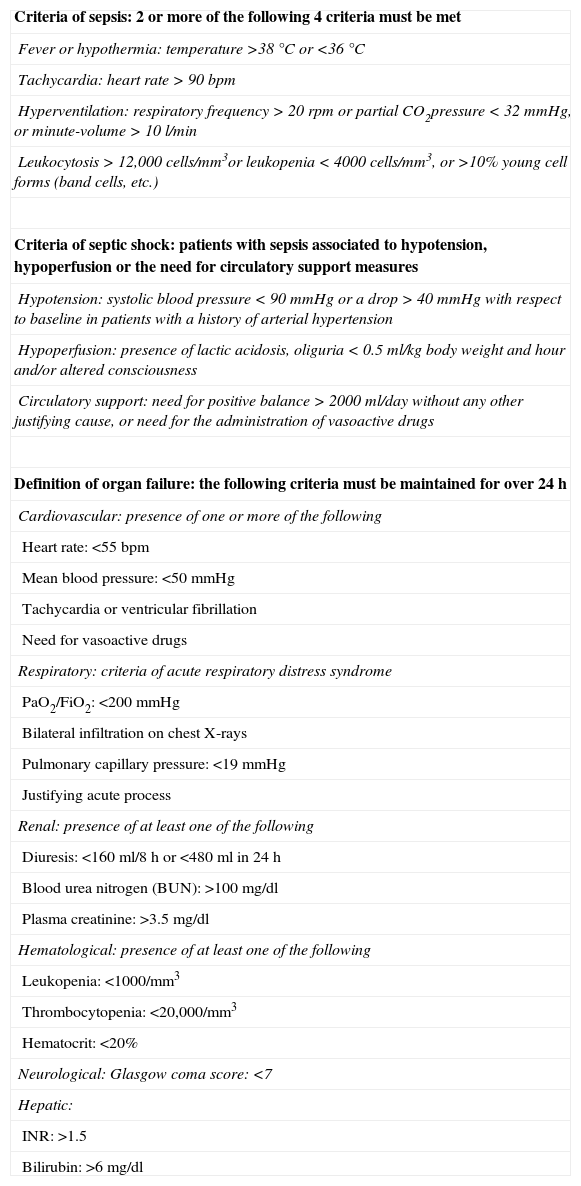

Patients and methodsOn a retrospective basis and covering a period of approximately 36 months, we included those patients over 18 years of age with severe sepsis admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Severe sepsis was diagnosed based on the presence of sepsis plus the failure of some organ, hypoperfusion or hypotension, in compliance with the criteria of the consensus conference of the American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine8 (Table 1). The demonstration of infection was also considered essential, using microbiological techniques (gram staining and/or culture), radiological techniques, or direct visualization of the infection site.

Criteria of sepsis, septic shock and of each type of organ failure.

| Criteria of sepsis: 2 or more of the following 4 criteria must be met |

| Fever or hypothermia: temperature >38°C or <36°C |

| Tachycardia: heart rate>90bpm |

| Hyperventilation: respiratory frequency>20rpm or partial CO2pressure<32mmHg, or minute-volume>10l/min |

| Leukocytosis>12,000cells/mm3or leukopenia<4000cells/mm3, or >10% young cell forms (band cells, etc.) |

| Criteria of septic shock: patients with sepsis associated to hypotension, hypoperfusion or the need for circulatory support measures |

| Hypotension: systolic blood pressure<90mmHg or a drop>40mmHg with respect to baseline in patients with a history of arterial hypertension |

| Hypoperfusion: presence of lactic acidosis, oliguria<0.5ml/kg body weight and hour and/or altered consciousness |

| Circulatory support: need for positive balance>2000ml/day without any other justifying cause, or need for the administration of vasoactive drugs |

| Definition of organ failure: the following criteria must be maintained for over 24h |

| Cardiovascular: presence of one or more of the following |

| Heart rate: <55bpm |

| Mean blood pressure: <50mmHg |

| Tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation |

| Need for vasoactive drugs |

| Respiratory: criteria of acute respiratory distress syndrome |

| PaO2/FiO2: <200mmHg |

| Bilateral infiltration on chest X-rays |

| Pulmonary capillary pressure: <19mmHg |

| Justifying acute process |

| Renal: presence of at least one of the following |

| Diuresis: <160ml/8h or <480ml in 24h |

| Blood urea nitrogen (BUN): >100mg/dl |

| Plasma creatinine: >3.5mg/dl |

| Hematological: presence of at least one of the following |

| Leukopenia: <1000/mm3 |

| Thrombocytopenia: <20,000/mm3 |

| Hematocrit: <20% |

| Neurological: Glasgow coma score: <7 |

| Hepatic: |

| INR: >1.5 |

| Bilirubin: >6mg/dl |

The following exclusion criteria were established:

- a)

Primary or acquired immunodeficiency of any kind

- b)

Previous immunosuppressive or immune modulating treatment

- c)

Uncontrolled or actively treated neoplastic disease

- d)

Active autoimmune or allergic disorders

- e)

The need for extrarenal filtration techniques capable of affecting clearance of the different inflammatory mediators

- f)

Administration of experimental therapy

We analyzed peripheral blood samples from 36 health volunteers (controls) with an age and gender distribution similar to that of the patients included in the study, in order to prevent the demographic characteristics from interfering with the interpretation of the results. The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee. The relatives of the patients and healthy controls gave informed consent to the experimental protocol.

All the patients received conventional treatment. None received activated protein C, and individuals needing hydrocortisone due to refractory hypotension were excluded from the study.

Blood samples were collected through the arterial catheter in tubes without anticoagulant in the first 12h after admission to the ICU (baseline sample), 48h after admission, and after 7, 14 and 28 days. An additional 10ml of blood was extracted and allowed to clot at room temperature, followed by serum separation by centrifugation at 600×g during 20min. The supernatants were collected, filtered and divided into aliquots that were stored frozen at −70°C until use.

After thawing of the supernatants to room temperature, sandwich ELISA testing was carried out. The results obtained were measured with the Multititer Plus® enzymoimmunoassay reader (Tiertek Multiscan Plus, Flow Laboratories, United Kingdom), and were compared with a standard curve obtained from known concentrations of each cytokine, supplied by the manufacturer.

The analysis of the different standard curves and subsequent interpolations were carried out with the Delta Soft II® version 4.1 software (Biometallies, Inc., USA) on a Macintosh® computer.

The determinations of the concentrations of the different cytokines were made using the commercial formulations with a supernatant quantitation sensitivity of 25pg/ml for IL-8 (Diaclone, USA), 5pg/ml for MCP-1 (R&D System, Minneapolis, USA), 10pg/ml for MIP-1α (R&D System, Minneapolis, USA), and 10pg/ml for RANTES (R&D System, Minneapolis, USA).

In relation to the statistical study, we first examined the nature of the distributions using the Shapiro–Wilk normality test. When the data obtained showed a normal distribution, comparisons of means were established using the Student t-test. In the case of data with a non-normal distribution, comparisons were made using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test. Comparison of data from one same group at different time intervals was carried out with the Friedman test, while correlations between the different variables were established using the Pearson correlation coefficient.

The results of the experimental studies are presented as the mean and standard error of the mean (sem). In all cases significance levels of under 5% were considered (p<0.05). The SPSS version 11.0 statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL 60606, USA) was used throughout.

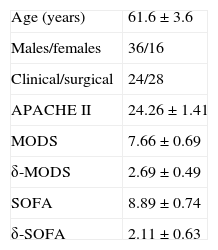

ResultsFig. 1 shows the flow of the 128 individuals studied, including 52 patients (all with septic shock), 40 excluded subjects and 36 healthy controls. The demographic characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 2.

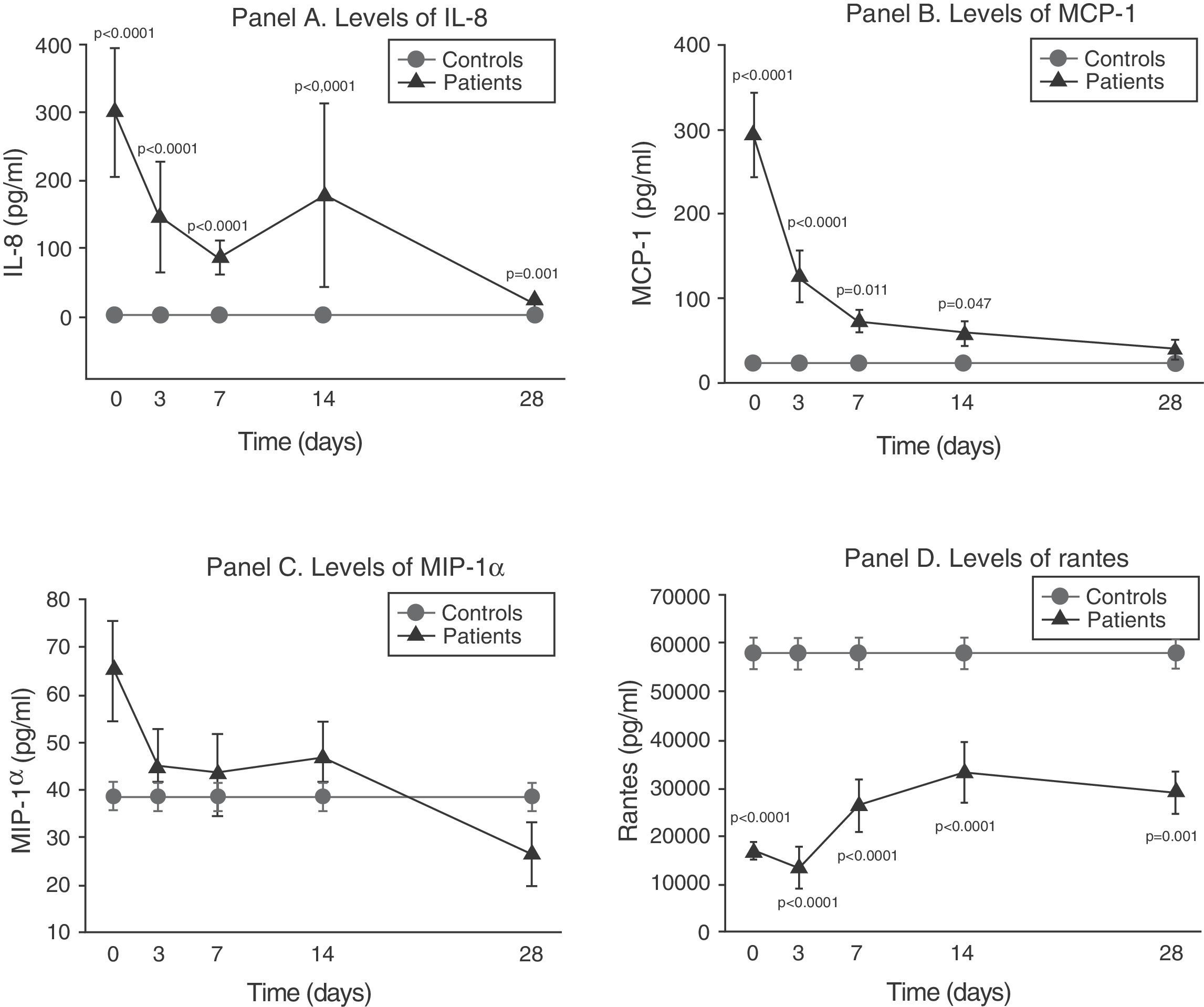

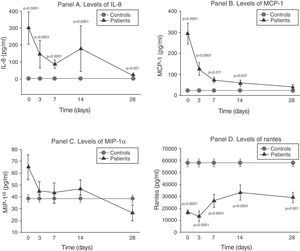

The serum levels of the studied soluble chemokines (IL-8, MCP-1, MIP-1α and RANTES) showed special and individualized behavior in each case.

As can be seen in panel A of Fig. 2, IL-8 maintained extraordinarily elevated levels throughout the evolution of sepsis.

Soluble chemokine levels in patients with septic shock. Panel A: levels of IL-8 in pg/ml versus time in days. Panel B: levels of MCP-1 in pg/ml versus time in days. Panel C: levels of MIP-1α in pg/ml versus time in days. Panel D: levels of RANTES in pg/ml versus time in days. The values are expressed as the mean and standard error of the mean.

The concentration of MCP-1 was very high in the first phase and then gradually decreased to normalization by day 28 (panel B of Fig. 2).

There were no significant differences between the levels of MIP-1α among the controls and in the patients at any timepoint (panel C of Fig. 2).

On the other hand, as can be seen in panel D of Fig. 2, the RANTES levels were below those of the controls at all timepoints of the disease.

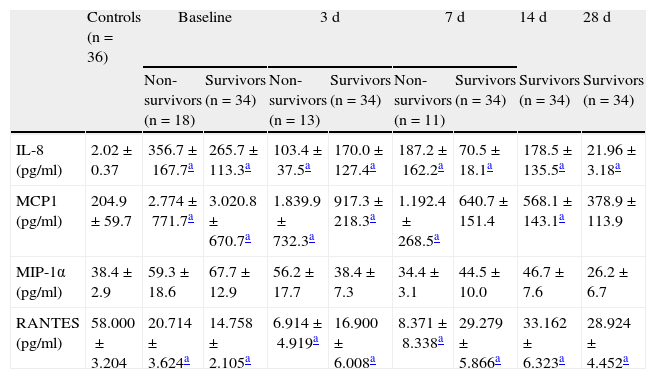

Prognostic value of the soluble chemokine levelsThe mortality rate among the patients was 34.6%. In the patients with septic shock, we found no significant differences in serum chemokine levels between the survivors and those who died (Table 3).

Chemokine levels in the control group and at each evaluative timepoint of sepsis.

| Controls (n=36) | Baseline | 3d | 7d | 14d | 28d | ||||

| Non-survivors (n=18) | Survivors (n=34) | Non-survivors (n=13) | Survivors (n=34) | Non-survivors (n=11) | Survivors (n=34) | Survivors (n=34) | Survivors (n=34) | ||

| IL-8 (pg/ml) | 2.02±0.37 | 356.7±167.7a | 265.7±113.3a | 103.4±37.5a | 170.0±127.4a | 187.2±162.2a | 70.5±18.1a | 178.5±135.5a | 21.96± 3.18a |

| MCP1 (pg/ml) | 204.9±59.7 | 2.774±771.7a | 3.020.8±670.7a | 1.839.9±732.3a | 917.3±218.3a | 1.192.4±268.5a | 640.7±151.4 | 568.1±143.1a | 378.9±113.9 |

| MIP-1α (pg/ml) | 38.4±2.9 | 59.3±18.6 | 67.7±12.9 | 56.2±17.7 | 38.4±7.3 | 34.4±3.1 | 44.5±10.0 | 46.7±7.6 | 26.2±6.7 |

| RANTES (pg/ml) | 58.000±3.204 | 20.714±3.624a | 14.758±2.105a | 6.914±4.919a | 16.900±6.008a | 8.371±8.338a | 29.279±5.866a | 33.162±6.323a | 28.924±4.452a |

The results are expressed as mean±standard error of the mean.

Among the 6 organ system failures considered (cardiovascular, acute respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS], acute renal failure [ARF], coagulopathy, liver failure and neurological failure), the incidence of liver failure (n=3) and of neurological failure (n=2) was so low that no conclusions can be drawn from the data obtained. On the other hand, all the patients met criteria of cardiovascular failure and were classified as presenting septic shock. The patients with ARDS upon admission totaled 46%, while the incidence of ARF was 36%, and that of coagulopathy 19%.

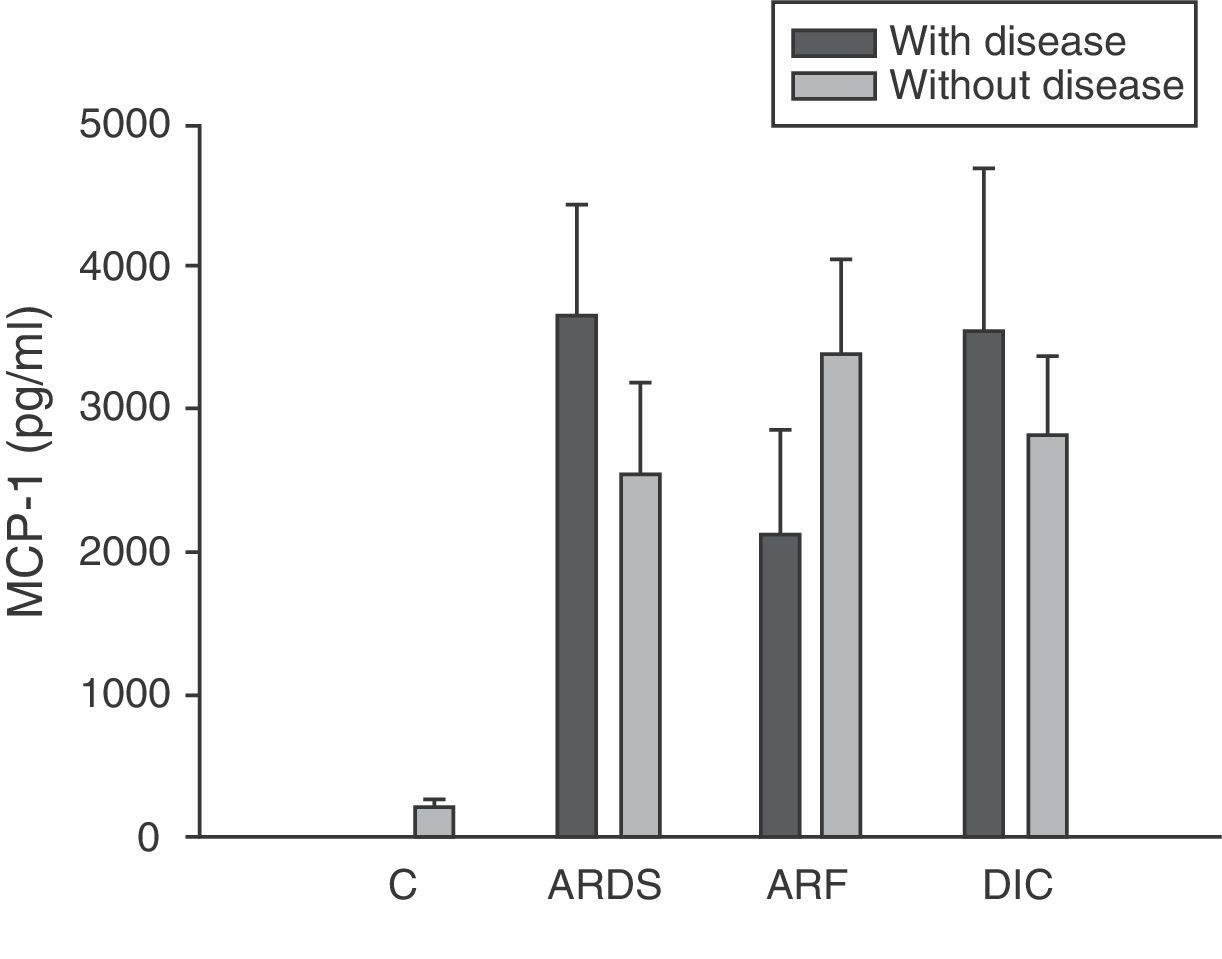

Analysis of the chemokine levels at the time of admission to the ICU and in relation to the different types of organ failure showed the serum levels of IL-8 to be significantly higher in the patients admitted with ARDS than in those without ARDS, and also in those with ARF compared with the patients who did not develop ARF (Fig. 3). In relation to the rest of the chemokines (MCP-1, MIP-1α and RANTES), no significant differences were observed at the time of admission in those with ARDS or in those with ARF (Figs. 4–6).

Levels of IL-8 in patients with septic shock upon admission to the ICU. C: controls; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; ARF: acute renal failure; DIC: disseminated intravascular coagulation. The criteria are specified in Table 1.

Levels of MCP-1 in patients with septic shock upon admission to the ICU. C: controls; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; ARF: acute renal failure; DIC: disseminated intravascular coagulation. The criteria are specified in Table 1.

Levels of MIP-1α in patients with septic shock upon admission to the ICU. C: controls; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; ARF: acute renal failure; DIC: disseminated intravascular coagulation. The criteria are specified in Table 1.

Levels of RANTES in patients with septic shock upon admission to the ICU. C: controls; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; ARF: acute renal failure; DIC: disseminated intravascular coagulation. The criteria are specified in Table 1.

The IL-8 and MIP-1α levels in the patients with coagulopathy were higher than in those without coagulopathy upon admission (Figs. 3 and 5). Significant differences were also observed in the levels of RANTES, with lower concentrations upon admission to the ICU in patients with coagulopathy than in those without (Fig. 6).

DiscussionIn the present study we found chemokines to be involved in the development of different types of organ damage. Interleukin-8 is increased in patients with septic shock, and these levels are good markers of respiratory, renal and hematological failure. Two other chemokines are also implicated in the case of patients with coagulopathy, namely MIP-1α and RANTES.

Hack et al.9 were the first to report that 89% of the patients with sepsis had high IL-8 levels upon admission and during follow-up over 60h, though in contrast to our own findings, the levels decreased in the course of follow-up. The physiopathological basis for this finding is the fact that endotoxin, IL-1β, and especially TNF-α are the main stimuli for IL-8 production and release. Measurement of the serum concentrations of IL-8 has been used to predict which patients have bacteremia in a group of subjects reporting to the emergency service due to systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS),10 though other authors prefer to use the procalcitonin levels for this purpose.11

A range of soluble molecules have been evaluated as potential prognostic markers in patients with sepsis.12–15 In this context, the prognostic usefulness of IL-8 concentration has been described by several authors.16,17

Recently, different studies using commercial multitests and simultaneously determining 17 molecules in patients with sepsis have found IL-8 to be one of the best prognostic biomarkers in patients of this kind.18–20 We and other investigators have not obtained such results.21 Possibly, the reason for this discrepancy is that our patients, in contrast to those of the other studies, were in a more serious condition, with higher APACHE II scores and practically all in a state of shock–this making it more difficult to find differences in the levels of IL-8. In effect, in the studies published by Halstensen et al.22 and Damas,16 patients with shock had higher levels than patients with sepsis but no cardiovascular failure.

Interleukin-8 has been identified as the main chemotactic factor of polymorphonuclear neutrophils in the lungs.23 Boutten et al.24 demonstrated a correlation between the neutrophil count and the concentration of IL-8 in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) obtained from different lung segments in 17 patients with unilateral pneumonia. We recorded higher IL-8 concentrations in patients with ARDS upon admission to the ICU than in those without ARDS. Some studies have analyzed this point and confirm our findings.16,25 It has been shown that the IL-8 levels in bronchoalveolar lavage are increased in patients with ARDS,26,27 and are moreover correlated to chronification of the disease.28

We observed significant differences in the levels of IL-8 among patients with ARF upon admission to the ICU as a consequence of sepsis. Fujishima et al.17 correlated the blood IL-8 levels to the development of ARF and mortality. The study published by Ahlström et al.29 likewise confirms our results. Interleukin-8 is probably implicated in the physiopathology of ARF in septic patients, though there are no conclusive experimental data in this respect. We therefore cannot discard the possibility that IL-8 elevation is simply a problem of renal clearance and accumulation of the molecule in situations of renal failure. In our study the IL-8 levels were higher in patients with coagulopathy at the onset of sepsis. The previously mentioned studies by Damas16 and Fujishima17 in septic patients confirm our data. Interleukin-8 is implicated in the induction of intravascular coagulation associated to endotoxin.30 It promotes the activation of coagulation, particularly through mediation by CD14+ monocytes.31 Thrombin in turn stimulates the production of IL-8 by monocytes and endothelial cells.31 An increase in blood IL-8 has also been described in coagulopathy associated to acute promyelocytic leukemia.32

Type 1 monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP-1) is a CC chemokine that acts as a mediator in monocyte and T lymphocyte tissue infiltration in a broad range of inflammatory diseases. In our study we recorded elevated MCP-1 levels upon admission compared with the control group, and these levels were seen to subsequently decrease progressively, with normalization after 28 days. These same results have been obtained by other authors.33,34 However, some investigators35 have only recorded elevated MCP-1 levels in the bronchoalveolar lavage of patients with sepsis, but not in serum. In this sense, we did not record elevated concentrations in patients with ARDS or any other organ failure upon admission. On the other hand, MCP-1 is admittedly regarded as a second signal and would be implicated in monocyte infiltration; consequently, at the time of admission it might not be possible to appreciate the clinical relevance which this mediator probably has at a later stage in time.

We found no differences in the serum MCP-1 levels during the first week of sepsis between the patients who died and those who survived. Similar results have been obtained by other authors.34

Macrophage inflammatory protein 1-α (MIP-1α) is fundamentally a macrophage chemotactic protein, although it has also been associated with chemotactic and proadhesive effects upon other cell types. MIP-1α also exerts modulating effects upon the production of cytokines, and is an endogenous pyrogen. Although experimentally MIP-1α appears after the administration of lipopolysaccharides both in vitro36 and in vivo,34,37 the results obtained on examining the serum levels in patients with severe sepsis were very notorious. In effect, we observed normal levels throughout the evolution of the disease, regardless of the prognosis. These same findings have been described by other groups.17,33–35,38

All authors appear to agree that the MIP-1α levels have no prognostic value or relation to the development of multiorgan failure.17,38 However, in our study we did observe differences in the levels of MIP-1α among the patients with coagulopathy upon admission to the ICU versus those without coagulopathy. The only study we have found in this line is the work published by Fujishima et al.,17 and although a tendency toward increased levels of MIP-1α was noted in the patients with coagulopathy, statistical significance was not reached.

The RANTES (regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted) protein is a CC chemokine produced by a series of cell types including platelets, lymphocytes and epithelial cells, in response to pyrogenic signals such as endotoxin, bacterial infections and TNF-α.39 Its main biological function is the trafficking and activation of both inflammatory and non-inflammatory cells.40 Cavaillon et al.41 reported that the levels of RANTES in sepsis are inversely proportional to the APACHE II score; the authors thus deduced that RANTES is lower among the patients who do not survive. Møller et al.33 demonstrated that patients with fulminant meningococcemia had lesser RANTES concentrations than patients with other less serious meningococcal infections.

We also observed extraordinarily low RANTES levels compared with the healthy controls. However, we did not find significant differences in the levels between the survivors and those patients who died. The only form of organ failure in which there were significantly lower concentrations in the patients was the presence of coagulopathy upon admission in the ICU versus those without coagulopathy. This result is difficult to interpret. It is known that bacteria can stimulate the release of RANTES,39 and that the administration of 4ng/kg of endotoxin to 8 healthy volunteers resulted in a drop in RANTES levels.42 On the other hand, we also know that platelets are the principal source of RANTES.43 Platelets express CD40 at surface level, which interacts with the CD154 receptor of activated T lymphocytes, inducing the release of RANTES stored in the platelets.43

During the inflammatory response, RANTES is released into the intravascular compartment and rapidly binds to the endothelial surface, thereby giving rise to the recruitment and retention of leukocytes–including T cells.40 This is where the interpretation difficulty lies: is the decrease in RANTES observed in coagulopathy attributable to depletion of the molecule upon binding to the vascular endothelium, or is it a consequence of a drop in the RANTES reservoir, i.e., the platelets? In hematological patients, Ellis et al.40 found that in subjects with fever, RANTES concentration is related to the presence of thrombocytopenia. We posteriorly studied the correlation between the levels of RANTES and the platelet counts in blood among patients with severe sepsis during the first day of admission to the ICU. This nonparametric association, studied by means of the Spearman test, yielded a correlation of 0.546, with p=0.007. We therefore cannot rule out the possibility that this decrease in RANTES levels among patients with coagulopathy is simply an expression of the thrombocytopenia found in these individuals.

In conclusion, in this study we have demonstrated the participation of chemokines IL-8, MIP-1α and RANTES in coagulopathy associated to septic shock, as well as the usefulness of IL-8 as a biomarker of respiratory and renal failure. Nevertheless, these molecules appear to lack prognostic value in patients with septic shock.

Financial supportThis study has been financed in part by the Community of Madrid, S-BIO-0189/2006, and by the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, PI-08-1890.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors thank the medical and nursing team of the ICU of Príncipe de Asturias University Hospital for their collaboration in this study.

Please cite this article as: de Pablo R, Monserrat J, Prieto A, Álvarez-Mon M. Papel de las quimioquinas solubles circulantes en el shock séptico. Med Intensiva. 2013;37:510–518.