In Spain, the management of arrhythmias falls within the competence of the specialty of Intensive Medicine.1 Some of our specialists are devoted to the management of definitive devices of cardiac pacing, and are responsible for 30%–40% of the therapies performed in our country each year.2,3 At national level, the Spanish Pacemaker Registry, elaborated with information from the European cards of pacemaker carriers submitted by the centers themselves, is not very much represented in the intensive care unit (ICU) setting, picking up just a few indirect parameters of healthcare quality.3 Since 1995, the Cardiological Intensive Care and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Working Group of the Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine and Coronary Units (SEMICYUC) has been studying the activity developed in this field through the MAMI (Database on definitive pacemakers in Intensive Medicine) registry. However, the progression of life expectancy and the diseases that benefit from these devices have induced changes of therapies and an increased use,3,4 which is indicative of the need to remodel the registry adapting it to contemporary reality so that it still remains a useful tool of activity and quality control.5,6

This study primary endpoint is to know the percentage of ICUs that are active in definitive cardiac pacing to quantify their importance and know what percentage of these ICUs would benefit directly from the registry. The study secondary endpoint is to describe these ICUs activity to know exactly towards what cardiac pacing settings should these changes point at. This was an observational study where the ICUs registered in the SEMICYUC database were submitted an online survey with variables on implantation, follow-up, and training during 2018. The list including all cardiac pacing implantation-capable units provided by the medical providers of cardiac pacing devices was contacted individually to confirm that the survey had been received. Cardiac pacing implantation-capable units were considered those that said so in the survey while cardiac pacing implantation-non capable units were considered the rest of them. Large hospitals were those with over 500 beds, medium-sized hospitals those between 500 and 200 beds, and small hospitals those with less than 200 beds. A descriptive analysis was performed using the SPSS 19 statistical package software. Qualitative variables were expressed as count and percentage, and quantitative variables as mean and standard deviation. Since this was an observational study without drugs where overall figures from administrative registries instead of data from patients were used, no assessment from any clinical research ethical committee was requested. Each center gave its informed consent before the publication of data.

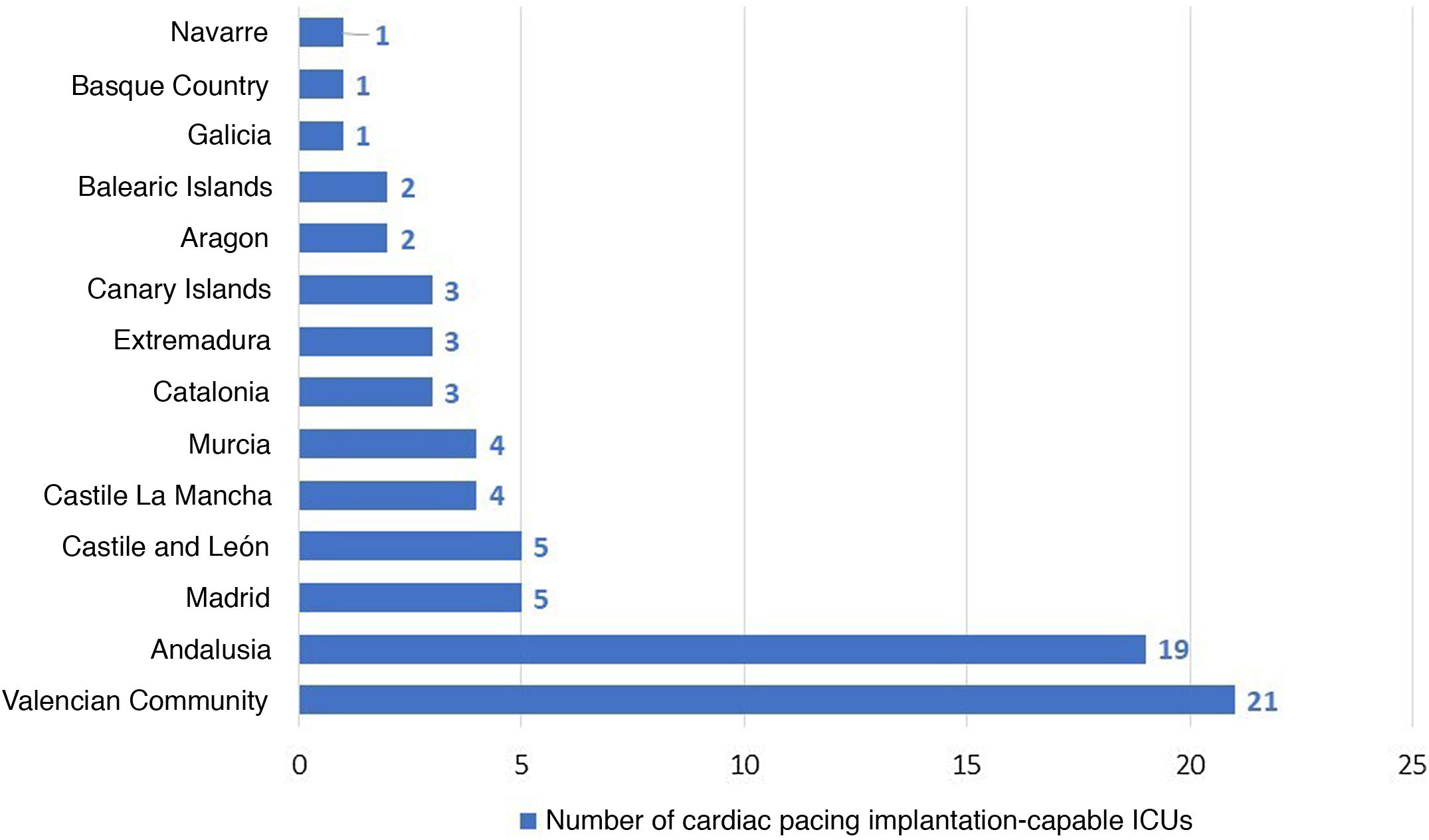

Overall, the survey was submitted to 212 ICUs and was responded by 91 ICUs (42.9%); 75 ICUs (35.4%) performed some type of definitive cardiac pacing activity. Centers were mostly public (n = 67; 89.3%) and medium-sized (n = 37; 49.4%) with teams of 3.5 ± 1.5 people and an irregular geographic distribution: the autonomous communities with more centers were Andalusia (n = 19; 25.3%), and Valencian Community (n = 18; 24%) (Fig. 1). In 4 of the cardiac pacing implantation-capable ICUs (5.7%) this activity is shared with the Cardiology unit.

Distribution by autonomous communities of the intensive care units that remain active in definite cardiac pacing device implantation. Each bar represents the number of intensive care units that remain active administering definitive cardiac pacing therapies in each autonomous community. ICU, intensive care unit.

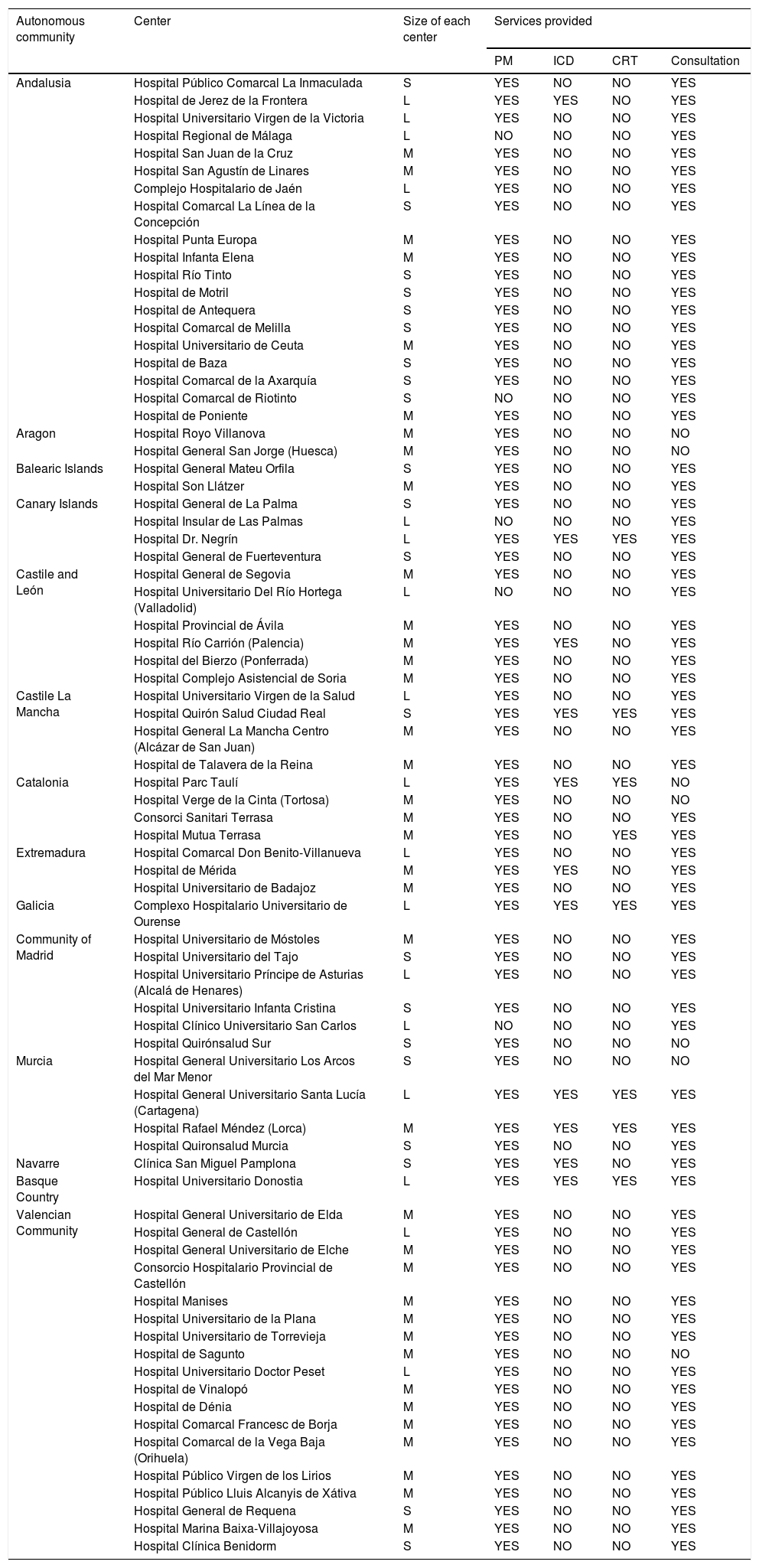

Table 1 describes the centers found and the activity performed there. Out of the 75 hospitals with some type of cardiac pacing activity, 5 (6.7%) only do follow-up and no implantation; only 70 hospitals do implant devices. Of these, 64 (85%) have units capable of performing not only the implantation by also the follow-up of the devices. Regarding the activity developed, 55 centers (78.6%) only implant pacemakers with an annual number of implantations >100 procedures. A total of 11 centers (15.7%) are also capable of implanting implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD), and 8 of them (11.5%) cardiac resynchronization therapy devices. A total of 30 (43.47%) out of the 69 centers that did the follow-up handle over 400 annual appointments. These figures are close not only to what the Spanish registry of 2018 reported on, but also to the data from 2018 provided by Farmaindustria both in the volume and type of devices implanted.3

Hospitals with intensive care units capable of administering definitive cardiac pacing therapies grouped by autonomous community.

| Autonomous community | Center | Size of each center | Services provided | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM | ICD | CRT | Consultation | |||

| Andalusia | Hospital Público Comarcal La Inmaculada | S | YES | NO | NO | YES |

| Hospital de Jerez de la Frontera | L | YES | YES | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria | L | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Regional de Málaga | L | NO | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital San Juan de la Cruz | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital San Agustín de Linares | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén | L | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Comarcal La Línea de la Concepción | S | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Punta Europa | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Infanta Elena | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Río Tinto | S | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital de Motril | S | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital de Antequera | S | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Comarcal de Melilla | S | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Universitario de Ceuta | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital de Baza | S | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Comarcal de la Axarquía | S | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Comarcal de Riotinto | S | NO | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital de Poniente | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Aragon | Hospital Royo Villanova | M | YES | NO | NO | NO |

| Hospital General San Jorge (Huesca) | M | YES | NO | NO | NO | |

| Balearic Islands | Hospital General Mateu Orfila | S | YES | NO | NO | YES |

| Hospital Son Llátzer | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Canary Islands | Hospital General de La Palma | S | YES | NO | NO | YES |

| Hospital Insular de Las Palmas | L | NO | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Dr. Negrín | L | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| Hospital General de Fuerteventura | S | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Castile and León | Hospital General de Segovia | M | YES | NO | NO | YES |

| Hospital Universitario Del Río Hortega (Valladolid) | L | NO | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Provincial de Ávila | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Río Carrión (Palencia) | M | YES | YES | NO | YES | |

| Hospital del Bierzo (Ponferrada) | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Complejo Asistencial de Soria | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Castile La Mancha | Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Salud | L | YES | NO | NO | YES |

| Hospital Quirón Salud Ciudad Real | S | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| Hospital General La Mancha Centro (Alcázar de San Juan) | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital de Talavera de la Reina | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Catalonia | Hospital Parc Taulí | L | YES | YES | YES | NO |

| Hospital Verge de la Cinta (Tortosa) | M | YES | NO | NO | NO | |

| Consorci Sanitari Terrasa | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Mutua Terrasa | M | YES | NO | YES | YES | |

| Extremadura | Hospital Comarcal Don Benito-Villanueva | L | YES | NO | NO | YES |

| Hospital de Mérida | M | YES | YES | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Universitario de Badajoz | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Galicia | Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense | L | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Community of Madrid | Hospital Universitario de Móstoles | M | YES | NO | NO | YES |

| Hospital Universitario del Tajo | S | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias (Alcalá de Henares) | L | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Universitario Infanta Cristina | S | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario San Carlos | L | NO | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Quirónsalud Sur | S | YES | NO | NO | NO | |

| Murcia | Hospital General Universitario Los Arcos del Mar Menor | S | YES | NO | NO | NO |

| Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía (Cartagena) | L | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| Hospital Rafael Méndez (Lorca) | M | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| Hospital Quironsalud Murcia | S | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Navarre | Clínica San Miguel Pamplona | S | YES | YES | NO | YES |

| Basque Country | Hospital Universitario Donostia | L | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Valencian Community | Hospital General Universitario de Elda | M | YES | NO | NO | YES |

| Hospital General de Castellón | L | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital General Universitario de Elche | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Consorcio Hospitalario Provincial de Castellón | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Manises | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Universitario de la Plana | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Universitario de Torrevieja | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital de Sagunto | M | YES | NO | NO | NO | |

| Hospital Universitario Doctor Peset | L | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital de Vinalopó | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital de Dénia | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Comarcal Francesc de Borja | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Comarcal de la Vega Baja (Orihuela) | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Público Virgen de los Lirios | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Público Lluis Alcanyis de Xátiva | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital General de Requena | S | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Marina Baixa-Villajoyosa | M | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

| Hospital Clínica Benidorm | S | YES | NO | NO | YES | |

ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillators; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; L, large; M, medium-sized; PM, pacemaker; S, small.

A tendency towards the use of more techniques associated with more physiological cardiac pacing, more atrioventricular synchrony, less atrial fibrillation and pacemaker syndrome like sequential pacing (54.4% in 2010 vs 84.5% in 2018), and active-fixation electrodes has been reported.3,6,7 In our series, the latter are used as a single model in 37.8% of the ICUs (n = 28), and as a predominant model in 89.2%, which is similar to the 88% rate published in the Spanish registry.3 The dual chamber sequential cardiac pacing was the most widely used pacing mode (84.2% of our centers) preferably using 2 wires (DDDR). If we compare the last results of the MAMI registry with the Spanish registry of the same year, we will see similar rates (DDDR 40.2% vs 43.6%, respectively) although somehow lower than the current ones (47.2%)3.

Echocardiography prior to implantation was always indicated in 54.3% of the centers (n = 38), in selected cases in 28.6% (n = 20), and was not performed at all in 21.4% (n = 15). It is possible that the percentage of patients without echocardiography has been overestimated if the echocardiographies performed in different units or services have not been taken into consideration. However, a review for the implementation of echocardiography would be the thing to do no since knowing the cardiac structure and the ventricular function bring understanding allow us to adjust the therapy to clinical practice guidelines, and optimize the decision-sharing process and clinical results.8,9

Back in 2014, and in an attempt to recognize competence and training capabilities in cardiac pacing SEMICYUC proposed a system of accreditation and training based on self-evaluation and further external auditing of specialists and units.10 According to our survey, 32 ICUs (45.7%) currently are holders of the SEMICYUC accreditation. Access to this accreditation may be limited by the lack of hospital infrastructures or for not having specific competences implemented in all the centers such as not doing any follow-ups (which discards 30.6% of the hospitals) or not having training capabilities (which discards 47.2% of the hospitals). The SEMICYUC accreditation also proposes targeted training with a specific program to homogenize training in cardiac pacing. According to our survery, this training plan was developed in 52.8% (n = 37) of the cardiac pacing implantation-capable units.

Since this analysis tried to capture the big picture of the activity going on in these centers, it never registered any healthcare quality parameters aside from those coming from the routine practices described above. Regardless of this, our results show that cardiac pacing is included in the services provided by a significant number of ICUs in our country. Also, that these ICUs perform a high volume of procedures and office consultations being pacemakers the most common devices of all. We should not forget that a fourth of all cardiac pacing implantation-capable units are also involved in the management of other devices. Based on these conclusions, we should say that keeping the activity of the registry going and adapted to the clinical reality described above can still be useful for a wide array of intensive care units. Having information from the registry available would allow us to analyze the quality of the entire process, make comparative assessments with other registries, and develop actions to improve healthcare that would be similar to the Zero projects born within the ENVIN registry.

FundingThis project received no funding whatsoever. The processes of disclosing the results of the survey, the online support, and the management of data have all been performed with resources and funds from SEMICYUC as part of a project within the activity developed by the Cardiological Intensive Care and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Working Group.

Conflicts of interestNone reported.

We would like to thank the founding team of the MAMI registry, especially Dr. García Urra, and Dr. Porres, and all intensivists who, throughout these 25 years, have developed their cardiac pacing activity and collaborated developing the registry.

Please cite this article as: Salazar Ramírez C, Nieto González M, Fernández Lozano JA, Muñoz Bono J, Gómez-López R, Martín Delgado MC, et al. Encuesta de situación en electroestimulación cardíaca en las unidades de cuidados intensivos en España. Med Intensiva. 2022;46:46–50.