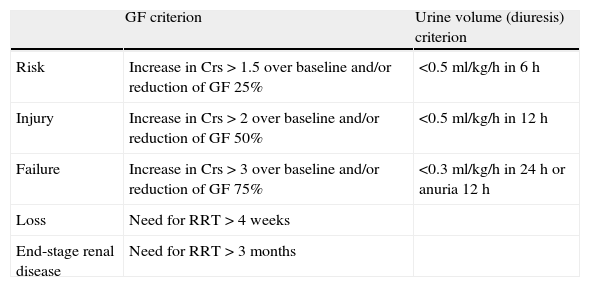

In the year 2004, publication was made of the recommendations of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI), developed by a group of intensivists and nephrologists for diagnosis and risk stratification in acute renal dysfunction (ARD) according to the RIFLE criteria.1 These criteria comprise three levels of dysfunction (risk, injury and failure) (Table 1), in accordance to the magnitude of the increase in serum creatinine (Crs) or the decrease in estimated glomerular filtration (eGF) and urine volume, and two outcome measures (loss and end-stage renal disease), according to the dependence upon renal replacement therapy (RRT).

RIFLE criteria for diagnosis and risk stratification in acute renal dysfunction.

| GF criterion | Urine volume (diuresis) criterion | |

| Risk | Increase in Crs>1.5 over baseline and/or reduction of GF 25% | <0.5ml/kg/h in 6h |

| Injury | Increase in Crs>2 over baseline and/or reduction of GF 50% | <0.5ml/kg/h in 12h |

| Failure | Increase in Crs>3 over baseline and/or reduction of GF 75% | <0.3 ml/kg/h in 24h or anuria 12h |

| Loss | Need for RRT>4 weeks | |

| End-stage renal disease | Need for RRT>3 months |

Crs: serum creatinine; GF: glomerular filtration; RRT: renal replacement therapy.

The RIFLE criteria have been validated with respect to mortality in many studies, with a progressive increase in risk parallel to the rise in degree of ARD.2 However, they also have important limitations, such as the need for a previous Crs determination in order to assess the change, a lack of correspondence between serum creatinine and glomerular filtration due to the open hyperbolic relationship between these two variables, the time delay in Crs elevation—with the consequent possibility of erroneously stratifying the patient on the RIFLE scale—and particularly the absence of equivalence in terms of vital prognosis between the two components of the definition with equal weighting (only one having to be met in order to be stratified). In effect, while the Crs criterion is a potent marker of mortality in the ICU, the same cannot be said of the urine volume (diuresis) criterion.3

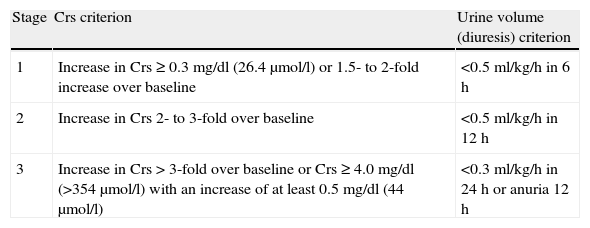

Because of these limitations, in 2007 the Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) proposed a revision of the diagnostic criteria and severity classification based on a modification of the RIFLE criteria for acute renal failure (ARF),4 along with a change in nomenclature to replace ARF with “acute renal dysfunction” (Table 2). The diagnostic criteria include a time profile (<48h), contemplate the Crs elevation (>50%) and urine volume (diuresis) reduction criteria (<0.5ml/h×6h) of the RIFLE risk stratification, and add an absolute Crs increment (>0.3mg/dl)—since epidemiological studies have shown such small Crs elevations to be independent predictors of mortality, mean hospital stay and cost.5 Furthermore, these diagnostic criteria would only be applicable after optimizing extracellular volume status and discarding obstruction, if only the diuresis criterion is used. Stages 2 and 3 only define more severe degrees of ARD according to Crs elevation and/or diuresis reduction criteria. However, compared with the RIFLE system, adoption of the AKIN classification does not substantially improve the sensitivity and early predictability of ARD in patients admitted to the ICU,6 since it remains dependent upon surrogate variables of renal injury that manifest relatively late and which do not reflect the nature or location of the injury.

AKIN criteria for diagnosis and risk stratification in acute renal dysfunction.

| Stage | Crs criterion | Urine volume (diuresis) criterion |

| 1 | Increase in Crs≥0.3mg/dl (26.4μmol/l) or 1.5- to 2-fold increase over baseline | <0.5ml/kg/h in 6h |

| 2 | Increase in Crs 2- to 3-fold over baseline | <0.5ml/kg/h in 12h |

| 3 | Increase in Crs>3-fold over baseline or Crs≥4.0mg/dl (>354μmol/l) with an increase of at least 0.5mg/dl (44μmol/l) | <0.3ml/kg/h in 24h or anuria 12h |

Crs: serum creatinine.

In any case, the adoption of these definitions and standardizations of the severity of ARD has represented an important advance when it comes to comparing epidemiological incidence data in different places and circumstances, and to using them as outcome variables in clinical intervention or prevention studies. In turn, a significant observation is the important clinical impact exerted by even small changes in Crs concentration, with the advised consideration of drug dose adjustment in these patients.

For all these reasons, the findings of the COFRADE study, published in this issue of Medicina Intensiva,7 come as a surprise. This study reflects the data of a survey of 42 ICUs with 836 beds in 32 hospitals throughout Spain, and contains clear screening bias due to the participation of ICUs which have a special interest in ARD—as evidenced by their participation for a number of years in the FRAMI study on the incidence of ARD among critical patients in our setting.8 The main results of the study show the estimation of glomerular filtration to be based on Crs in 37% of the Units, minute clearance in 42%, and equations in 22%—when in fact it has been clearly demonstrated that these approaches are of little use in this population of critical patients with ARD.9 Furthermore, only 39% of the ICUs use ARD defining and risk stratification systems (RIFLE in 13 and AKIN in 3). In contrast, 64% of the Units follow written protocols for the management of RRT, 71% have adopted training programs in RRT, and 54% follow some drug dose adjustment method in patients subjected to RRT.

Based on the conclusions and recommendations of Herrera-Gutie¿rrez et al., from here we stress the need for a change in strategy for addressing ARD in the ICU with the incorporation of the RIFLE and AKIN criteria to routine clinical practice, with the purpose of promoting the early detection of ARD and thus being able to establish secondary prevention protocols to limit the damage and improve patient safety, avoiding drug dosing errors. All this applies while we await the development of new and more sensitive and specific biomarkers10 than those used to date by the ADQI and AKIN conferences (i.e., Crs and diuresis) for diagnosis and risk stratification in ARD.

Please cite this article as: Barrio V. Necesidad y utilidad del empleo de criterios estandarizados para el diagnóstico de la disfunción renal aguda en pacientes críticos. Med Intensiva. 2012;36:247–9.