The clinical profile of Hospital Acquired Sepsis (HAS) is poorly known. In a recent work,1 we found that patients suffering from HAS show many of the risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Lymphopenia is a frequent finding in sepsis patients.2–4 Sepsis affects the immune system by directly altering the lifespan, production and function of the effector cells responsible for homeostasis.5 Lymphopenia is also found in other severe infections like pneumonia needing of hospitalization, and it is associated to an increased risk of mortality.6

The impact of lymphocyte counts on the prognosis of patients with HAS is unknown. The objective of the present study was to evaluate the association between lymphocyte counts and mortality risk of the patients suffering from HAS. The predictive ability of the other leukocyte subpopulations was also assessed.

The study was approved by the Clinical Research and Ethics Committee of our hospital. Informed consent was waived due to the observational nature of the study.

A total of 196 patients were included in the study. Hospital and 90 days mortality was 45.4%. The median age of HAS patients was of 73 years (IQR: 68.1–71.4), with 68.4% (n=134) of them being male. Some serious comorbidities were: cardiac disease 63.8% (n=125), cancer 34.2% (n=67), chronic kidney disease 19.4% (n=38), immunosuppression 17.9% (n=35) and chronic hepatic disease 6.1% (n=12) (Supplementary Table 1). Sepsis with organ failure (severe sepsis/septic shock) was present in 146 patients (74.5%) with 75 of these patients dying during the first 90 days.

HAS emerged 10 days following hospital admission in median (IQR, 11.4–14.5). The most frequent source of infection was the respiratory tract (29.1%), followed by bacteraemia (25%) (Supplementary Table 1). Microorganisms were isolated in one hundred and fifty patients (76.5%). Gram negative bacteria were the most common microorganisms (58.6%), followed by Gram positive cocci (46.0%).

We collected leukocyte subpopulations counts at hospital admission and also at HAS diagnosis. Patients with HAS showed a significant increase in the median values of neutrophil counts from admission to diagnosis: (5.3 [4.00–7.4]×103/mm3) vs (10.9 [6.5–17.0]×103/mm3) p<0.001. On the contrary, median values of eosinophil and lymphocyte counts decreased from admission to diagnosis: (0.11 [0.04–0.22]×103/mm3) vs (0.02 [0.00–0.11]×103/mm3) for eosinophils and (1.6 [1.0–2.3]×03/mm3) vs (0.8 [0.4–1.3]×103/mm3]) for lymphocytes (with differences yielding a p<0.001 in both cases). Median values of monocytes and basophil counts did not change in a significant manner between both moments.

Median values of lymphocytes at HAS diagnosis were higher in survivors than in non survivors. Survivors showed also higher median values of eosinophils at HAS diagnosis than non survivors. On the contrary, monocyte, basophil and neutrophil counts did not show differences between both groups (Supplementary Table 1).

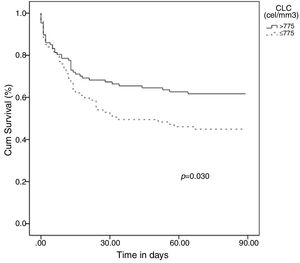

Lymphocytes and eosinophil counts at HAS diagnosis showed significant AUCs for identifying survivors at hospital discharge (Supplementary Fig. 1), with an (AUC [CI95%], p) of (0.59 [0.59–0.67], 0.042) and (0.60 [0.52–0.68], 0.023) respectively. Other leukocyte subtypes failed to discriminate survivors from non survivors. The optimal operating point (OOP) was calculated for those leukocyte subpopulations showing an AUC p<0.05 as previously described7 for distinguishing between both kinds of patients in the AUC analysis was 775cells/mm3 for lymphocytes and 13cells/mm3 for eosinophils.

Categorical variables were created based on the OOPs and the resulting variables for lymphocyte and eosinophil counts were evaluated for hospital mortality prediction using multivariate analysis adjusting by the potential confounding factors selected in the univariate analysis: [Age(years)], [Sex(male)], [“Sepsis code” implemented], [antecedent of vascular disease], [antecedent of cancer], [antecedent of chronic kidney disease], [sepsis with organ failure], [more than one episode of sepsis during hospital admission], [surgical intervention] and [time (days) from admission to sepsis diagnosis]. The presence of a lymphocyte count ≤775cells/mm3 at diagnosis of HAS was an independent predictor of mortality in the multivariate analysis: (1.98 [1.00–3.92], p=0.049) (OR 1.98 [CI 95% 1.00–3.92], p = 0.049) (Table 1). In turn, showing a eosinophil count ≤13cells/mm3 at diagnosis of HAS conferred a non-significant higher risk of mortality (1.87 [0.95–3.70], p=0.072). Finally, the Kaplan–Meier curves at 90 days following diagnosis of HAS showed that patients with ≤775lymphocytes/mm3 died earlier (media 48.6 days [40.3–56.8]) than patients with >775lymphocytes/mm3 (media 60.5 [53.1–67.9]), p=0.030 (Fig. 1).

Multivariate regression analysis to predict hospital mortality risk in patients with ≤775lymphocytes/mm3 at diagnosis of HAS.

| Variables | Hospital mortality | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | p | |

| Age (years) | 1.034 | [1.002–1.067] | 0.040 |

| Sex (male) | 2.067 | [0.978–4.369] | 0.057 |

| “Sepsis Code” implemented | 0.583 | [0.294–1.157] | 0.123 |

| Vascular disease | 1.419 | [0.650–3.096] | 0.380 |

| Cancer | 1.385 | [0.680–2.818] | 0.369 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.693 | [0.713–4.021] | 0.233 |

| Sepsis with organ failure | 4.687 | [1.889–11.629] | 0.001 |

| More than one episode of sepsis during hospital admission | 3.346 | [1.529–7.324] | 0.003 |

| Time (days) from admission to sepsis diagnosis | 1.036 | [1.000–1.074] | 0.050 |

| Surgical intervention | 0.316 | [0.144–0.696] | 0.004 |

| ≤775lymphocytes/mm3 | 1.983 | [1.004–3.919] | 0.049 |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

HAS was characterized by a significant increase in the blood counts of the paradigmatic cell representing innate immunity, the neutrophil, accompanied by a decrease in the prototypic cell of the adaptive immunity, the lymphocyte. Neutrophil count expansion could represent a kind of compensatory mechanism responding to the decrease in the lymphocyte counts, which precedes the emergence of HAS. The significant decrease in lymphocyte counts found from admission to diagnosis of HAS cannot be explained by hemodilution due to fluid administration, since counts of the other leukocyte subsets were not affected. In consequence, this is the first report providing evidence that sepsis does induce diminution of lymphocyte counts in blood.

Early identification of patients at risk of death is a crucial step in the clinical management of sepsis.8–10 In this regard, this study provides a cut-off value for lymphocyte counts (≤775cells/mm3) which is useful for the early identification of those patients at higher risk of mortality, independently of their accompanying co-morbidities (Table 1) (Fig. 1). Also we repeat analysis excluding immunosuppressed patients and we found that those patients with ≤775 lymphocytes/mm3 continue presenting higher risk to mortality.

Lymphocyte counting is a simple and inexpensive test, widely available in most hospital settings. In our study, the eosinophil count at diagnosis of HAS conferred a nonsignificant higher risk of mortality. Some limitations of our work were its retrospective nature, the absence of some variables like the albumin levels or severity scores like SOFA or APACHE.

In conclusion, lymphopenic HAS (L-HAS) (≤775lymphocytes/mm3) constitutes a particular immunological phenotype of the disease conferring a two-fold increase in the risk of hospital mortality. Patients with L-HAS deserve special care and close monitoring of vital signs.

Conflict of interestNone.

FundingThis research did not received any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Salaries from the authors are paid by the “Consejería de Sanidad de Castilla y León, Spain”.

Institution where the work was done: Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid, Av. Ramón y Cajal, 3, 47003, Valladolid, Spain.