Lower risk of catheter-related bacteremia (CRB) using taurolidine (antimicrobial agent) sealing of central venous catheters (CVCs) in children has been found in a meta-analysis.

The objective of this study was to analyze whether the sealing of unused lumens of CVCs with taurolidine in critically ill adult patients reduce CRB incidence.

DesignRetrospective study.

SettingOne Spanish Intensive Care Unit.

PatientsCritically ill adult patients, who underwent to some CVC.

InterventionsThe seal of unused lumens of CVCs was performed with saline serum 0.9% or taurolidine.

Main variable of interestPrimary Bloodstream Infection (PBSI) included catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI) CRBSI and bloodstream infection of unknown origin (BSIUO).

ResultsWe diagnosed 22 PBSI in the 573 (3.8%) CVC without taurolidine and 22 PBSI in the 548 (4.0%) CVC with taurolidine (p = 0.88). Logistic regression analysis showed an association of tracheostomy with the risk of PBSI; however, we did not find the association of other variables (included taurolidine) with the risk of PBSI.

ConclusionTo the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting data about sealing of unused lumens of CVCs with taurolidine in critically ill adult patients. In our preliminary study, we have not been able to demonstrate that sealing unused lumens of CVCs with taurolidine can reduce the risk of PBSI in critically ill adult patients. However, it would be interesting to conduct randomized studies to confirm or discard our findings.

Se ha objetivado en un meta-análisis un menor riesgo de bacteriemia relacionada con catéter (CRB) utilizando taurolidina (agente antimicrobiano) para el sellado de catéteres venosos centrales (CVCs) en niños. El objetivo de este estudio fué analizar si el sellado de las luces no utilizadas de CVC con taurolidina en pacientes críticos adultos reduce la incidencia de CRB.

DiseñoEstudio retrospectivo.

ÁmbitoUna Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos española.

PacientesPacientes críticos adultos con algún CVC.

IntervencionesSellado de las luces no utilizadas de CVC con taurolidina o con suero salino 0.9%.

Variable de interés principalBacteriemia primaria (PBSI), que incluía bacteriemia relacionada con catéter (CRBSI) y bacteriemia de origen desconocido (BSIUO).

ResultadosSe diagnosticaron 22 PBSI en los 573 (3.8%) CVC sin taurolidina y 22 PBSI en los 548 (4.0%) CVC con taurolidina (p = 0.88). El análisis de regresión logistica mostró la asociación de traqueostomía con el riesgo de PBSI; sin embargo, no encontramos la asociación con otras variables (incluída taurolidina) con el riesgo de PBSI.

ConclusionesQue nosotros sepamos, este es el primer estudio que aporta datos sobre el sellado de las luces no utilizadas de CVC con taurolidina en pacientes críticos adultos. En un estudio preliminar, no hemos sido capaces de demostrar que el sellado de las luces no utilizadas de CVC con taurolidina puede reducir el riesgo de PBSI en pacientes críticos adultos. Sin embargo, sería interesante realizar estudios aletorizados para confirmar o descartar nuestros resultados.

Vascular catheter-related bacteremia (CRB) leads to an increase in morbidity and mortality and care costs.1–4 For this reason, different measures to try to avoid it have been analyzed by different scientific societies.5–10

To avoid thrombosis and/or infection of vascular catheters there has been proposed to fill the lumens that are not used with different products, such as 0.9% saline serum or different agent dissolved in 0.9% saline solution (as heparin, ethanol, taurolidine). Taurolidine has a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity against gram-positive bacteria (including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin resistant Enterococcus), gram-negative bacteria and fungi.

Some scientific societies have suggested in their clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) to prevent central venus catheter (CVC) associated bacteremia that sealing catheter lumens with antimicrobials in certain patients could be considered but not routinely, as in CPGs of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) published in 2014,5 of the United Kingdom Department of Health published in 2014,6 and of the Asia Pacific Society of Infection Control (APSIC) published in 2016.7 In addition, CPGs of the SHEA5 and of APISC7 specified that it could be used in patients with long-term haemodialysis catheters, in patients with limited venous access and recurrent CRB, in patients at high risk of serious sequelae from CRB (patients with recent prosthetic heart valve or aortic graft implantation) or in paediatric cancer patients with long-acting catheters. However, its use has not been analyzed in the CPGs of Argentina published in 2019,8 France published in 2020,9 Spain published in 2021,10 SHEA, Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC), American Hospital Association (AHA) Joint Commission published in 2022,11 and International Society for Infectious Diseases (ISID) published in january 2025,12

Several meta-analyses have been published in recent years that concluded that sealing unused vascular catheter lumens with taurolidine leds to a reduction in CRB in certain patients.13–16 In a meta-analysis published by Kavosi et al. in 2016, including 3 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) with 280 hemodialysis catheters, a lower risk of CRB was observed with taurolidine-citrate vs. heparin sealing.13 A meta-analysis published by van den Bosch et al. in 2022 included 14 RCTs and 1219 patients with catheters for haemodialysis, for total parenteral nutrition or of oncologic patients, in which the rate of CRB and adverse events were compared with taurolidine sealing vs other seals (saline or heparin); and lower BRC rate was observed with taurolidine sealing compared to other seals (9 RCTs with 918 patients; RR = 0.30; 95% CI = 0.19−0.46) encompassing all catheters, but it was not analyzed independently the effect for each type of catheter.14 In a meta-analysis published by Vernon-Roberts et al. in 2022 including 34 studies (RCTs and non-RCTs) of patients with total parenteral nutrition, lower CRB was observed with taurolidine sealing (RR = 0.49; 95% CI = 0.46−0.53) compared to other seals (saline, heparin or ethanol).15 In a meta-analysis published by Sun et al. in 2020, including 4 RCTs with 476 CVCs in children, a lower risk of CRB was observed with taurolidine sealing vs control (saline or heparin).16 However, there are not reported data about CRB in CVC of critically ill adult patients using taurolidine sealing. Thus, the objective of this study was to analyze whether the sealing of unused lumens of CVCs with taurolidine in critically ill adult patients reduce the risk of CRB.

Material and methodsDesign and subjectsThis retrospective study was carried out in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) of the Hospital Universitario de Canarias (Tenerife, Spain). The study was approved by the Institutional Ethic Review Board (CHUC_2024_18) and the requirement of written informed consent for participate in the study was waived. We included patients with some CVC. There were included patients admitted to ICU between 1 April 2023 and 31 March 2024.

Unused lumens of CVCs were sealing with saline serum 0.9% or taurolidine dissolved in saline serum 0.9%. When one unused lumen of CVCs was sealed with saline, it was administered again every 12 h while that lumen was not used; and when unused lumens were reused and subsequently discontinued, the process was repeated, and saline was administered at that moment and afterwards every 12 h. When the unused lumens of CVCs were sealed with taurolidine, it was administered again every 30 days while these lumens were not used; and when unused lumen was reused and subsequently discontinued, the process was repeated, and taurolidine was administered at that moment and afterwards every 30 days. The responsible physician of each patient decided the type of sealing of unused lumens of CVCs for each patient. Patients were managed according to the usual clinical practice in the unit.

DefinitionsWe use the criteria of European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control for definitions of infections.17 We considered catheter tip colonization when a significant growth on the CVC tip of a microorganism was obtained by semi-quantitative method of Maki (≥15 colony-forming units).18 Catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI) was defined as the presence of the same recognized pathogen in the blood culture and in the CVC tip without other apparent source of infection. Bloodstream infection of unknown origin (BSIUO) was defined as the presence of bloodstream infection in patients with CVC and without no other apparent source of infection. Primary Bloodstream Infection (PBSI) included CRBSI and BSIUO. Two positive blood cultures (obtained in a separation of 48 h) for a common skin contaminant (Micrococcus spp., Coagulase-negative staphylococci, Cutibacterium acnes, Corynebacterium spp. and Bacillus spp.) were required. Therefore, some PBSIs had positive colonization of the CVC tip and others will not. Bloodstream Infection secondary to other infection site (BSI-S) was defined as the presence of the same pathogen in the blood culture and in other site.

Variables recordedWe recorded the following data from patients: age, sex, type of patient, reason for admission, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, oncological process, mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, parenteral nutrition, antimicrobials iv, organ trasplantation, ischemic heart disease, obesity, chronic renal failure, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE)-II score,19 duration of ICU stay, and exitus intra-UCI. In addition, we recorded the following data from CVC: catheter site (subclavian, jugular, femoral), type sealing type of unused lumens of CVCs (taurolidine or saline), time with CVC and presence of PBSI and BSI-S.

Measures for prevention of vascular catheter-related bacteremiaWe implement the following measures for prevention of CVC associated bacteremia according the Spanish Bacteremia Zero Project12: hand washing before CVC insertion with alcoholic solution (or in case of organic residues on the hands with chlorhexidine gluconate antiseptic soap), cleaning the skin around CVC insertion with 2% alcoholic chlorhexidine solution (70° alcohol or povidone only if there is hypersensitivity to chlorhexidine), full barrier precautions during the insertion of CVCs (with sterile gown, sterile drapes large enough to cover the patient, sterile gloves, mask and cap), avoiding the femoral site, removing unnecessary catheters, and proper catheter maintenance.

The proper catheter maintenance included the following aspects: Hand washing with alcoholic solution. Sterile gloves and cleaning the skin with 2% alcoholic chlorhexidine solution for dressing change and for healing of the insertion site. Minimize the handling of connections. We use transparent, not antimicrobial impregnated dressing that were changed once a week and when visibly soiled, wet or peeling. Sealing of the connections with sterile closed system plug (split septum valve). Clean the injection ports (after hand washing with alcoholic solution and with sterile gloves) with isopropyl alcohol 70 ° before accessing the system. The connecting lines were changed every 96 h.

We used CVC type ARROWg+ard Blue® (Arrow, Reading, PA, United States), which were impregnated on chlorhexidine-silver sulfadiazine on the external and internal surfaces). No impregnated dressings or antiseptic caps were used.

Statistical analysisWe reported categorical variables as number (%) and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test and continuous variables by the t-test. We performed a multivariate regression analysis to determine whether the sealing of unused lumens of CVCs with taurolidine reduced independently the risk of PBSI controlling for other risk factors. In the regression analysis we included the sealing with taurolidine and those variables that showed a p-value≤0.05 in the comparison of CVC with or without PSBI (mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, duration of CVC and APACHE-II). We carried out statistical analyses with SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) and we considered P values lower than 0.05 as significant.

ResultsA total of 1121 CVCs (573 without taurolidine and 548 with taurolidine) were included in the study. We diagnosed 44 PBSI in those 1121 CVC that remaining placed for 8636 days, thus the density incidence of PBSI was of 5.09/1000 CVC-days. We diagnosed 22 PBSI in the 573 (3.8%) CVC without taurolidine and 22 PBSI in the 548 (4.0%) CVC with taurolidine (p = 0.88).

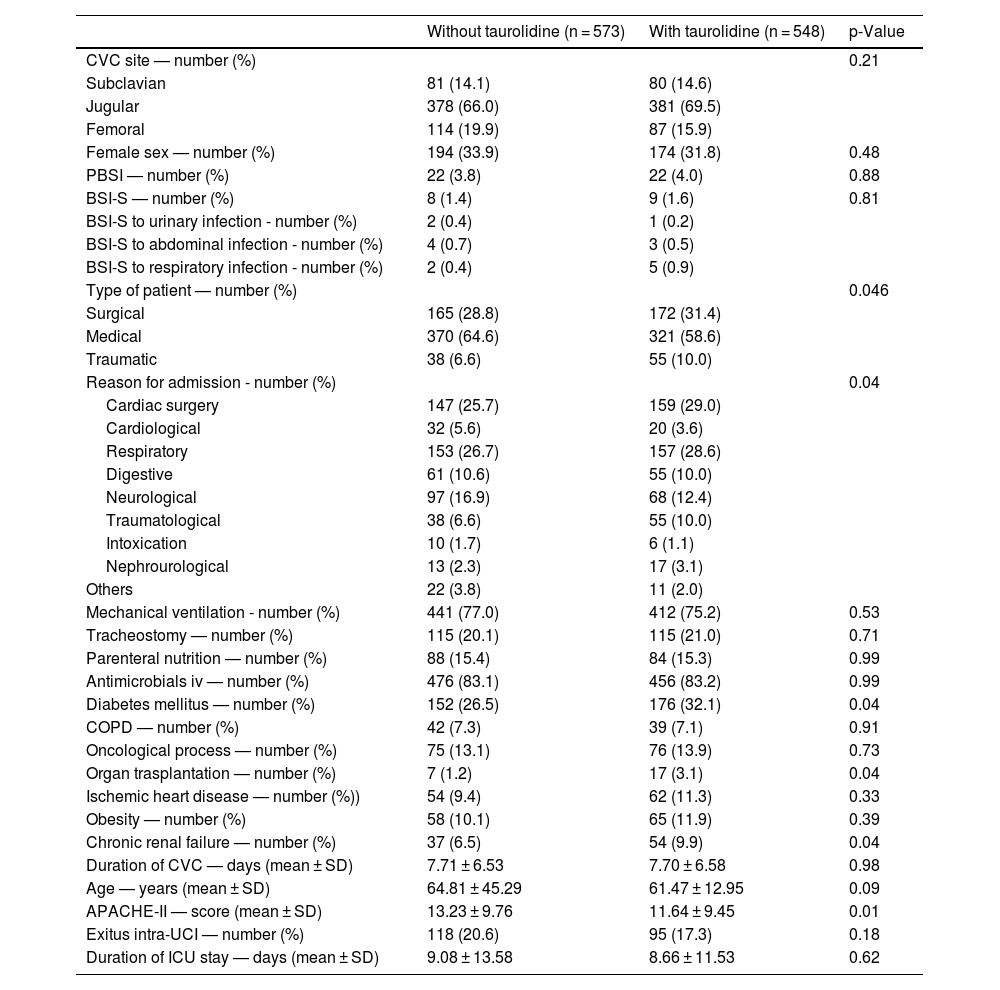

Table 1 shows the comparison of CVCs with and without taurolidin. We found that CVCs with taurolidin showed a higher rate of diabetes mellitus (p = 0.04), organ trasplantation (p = 0.04). and chronic renal failure (p = 0.04), and lower APACHE-II (p = 0.01) that CVCs without taurolidin. Besides, there were differences between CVCs with and without taurolidin on type of patient (p = 0.046). There were not found significant differences between CVCs with and without taurolidin on CVC access, sex, PBSI, BSI-S, reason for admission, mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, parenteral nutrition, antimicrobials iv, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, oncological process, ischemic heart disease, obesity, duration of CVC, duration of ICU stay, and age.

Characteristics of central venous catheters (CVC) with and without taurolidine.

| Without taurolidine (n = 573) | With taurolidine (n = 548) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CVC site — number (%) | 0.21 | ||

| Subclavian | 81 (14.1) | 80 (14.6) | |

| Jugular | 378 (66.0) | 381 (69.5) | |

| Femoral | 114 (19.9) | 87 (15.9) | |

| Female sex — number (%) | 194 (33.9) | 174 (31.8) | 0.48 |

| PBSI — number (%) | 22 (3.8) | 22 (4.0) | 0.88 |

| BSI-S — number (%) | 8 (1.4) | 9 (1.6) | 0.81 |

| BSI-S to urinary infection - number (%) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | |

| BSI-S to abdominal infection - number (%) | 4 (0.7) | 3 (0.5) | |

| BSI-S to respiratory infection - number (%) | 2 (0.4) | 5 (0.9) | |

| Type of patient — number (%) | 0.046 | ||

| Surgical | 165 (28.8) | 172 (31.4) | |

| Medical | 370 (64.6) | 321 (58.6) | |

| Traumatic | 38 (6.6) | 55 (10.0) | |

| Reason for admission - number (%) | 0.04 | ||

| Cardiac surgery | 147 (25.7) | 159 (29.0) | |

| Cardiological | 32 (5.6) | 20 (3.6) | |

| Respiratory | 153 (26.7) | 157 (28.6) | |

| Digestive | 61 (10.6) | 55 (10.0) | |

| Neurological | 97 (16.9) | 68 (12.4) | |

| Traumatological | 38 (6.6) | 55 (10.0) | |

| Intoxication | 10 (1.7) | 6 (1.1) | |

| Nephrourological | 13 (2.3) | 17 (3.1) | |

| Others | 22 (3.8) | 11 (2.0) | |

| Mechanical ventilation - number (%) | 441 (77.0) | 412 (75.2) | 0.53 |

| Tracheostomy — number (%) | 115 (20.1) | 115 (21.0) | 0.71 |

| Parenteral nutrition — number (%) | 88 (15.4) | 84 (15.3) | 0.99 |

| Antimicrobials iv — number (%) | 476 (83.1) | 456 (83.2) | 0.99 |

| Diabetes mellitus — number (%) | 152 (26.5) | 176 (32.1) | 0.04 |

| COPD — number (%) | 42 (7.3) | 39 (7.1) | 0.91 |

| Oncological process — number (%) | 75 (13.1) | 76 (13.9) | 0.73 |

| Organ trasplantation — number (%) | 7 (1.2) | 17 (3.1) | 0.04 |

| Ischemic heart disease — number (%)) | 54 (9.4) | 62 (11.3) | 0.33 |

| Obesity — number (%) | 58 (10.1) | 65 (11.9) | 0.39 |

| Chronic renal failure — number (%) | 37 (6.5) | 54 (9.9) | 0.04 |

| Duration of CVC — days (mean ± SD) | 7.71 ± 6.53 | 7.70 ± 6.58 | 0.98 |

| Age — years (mean ± SD) | 64.81 ± 45.29 | 61.47 ± 12.95 | 0.09 |

| APACHE-II — score (mean ± SD) | 13.23 ± 9.76 | 11.64 ± 9.45 | 0.01 |

| Exitus intra-UCI — number (%) | 118 (20.6) | 95 (17.3) | 0.18 |

| Duration of ICU stay — days (mean ± SD) | 9.08 ± 13.58 | 8.66 ± 11.53 | 0.62 |

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; PBSI: primary bloodstream infection; BSI-S: bloodstream infection secondary to other infection site; SD = standard deviation.

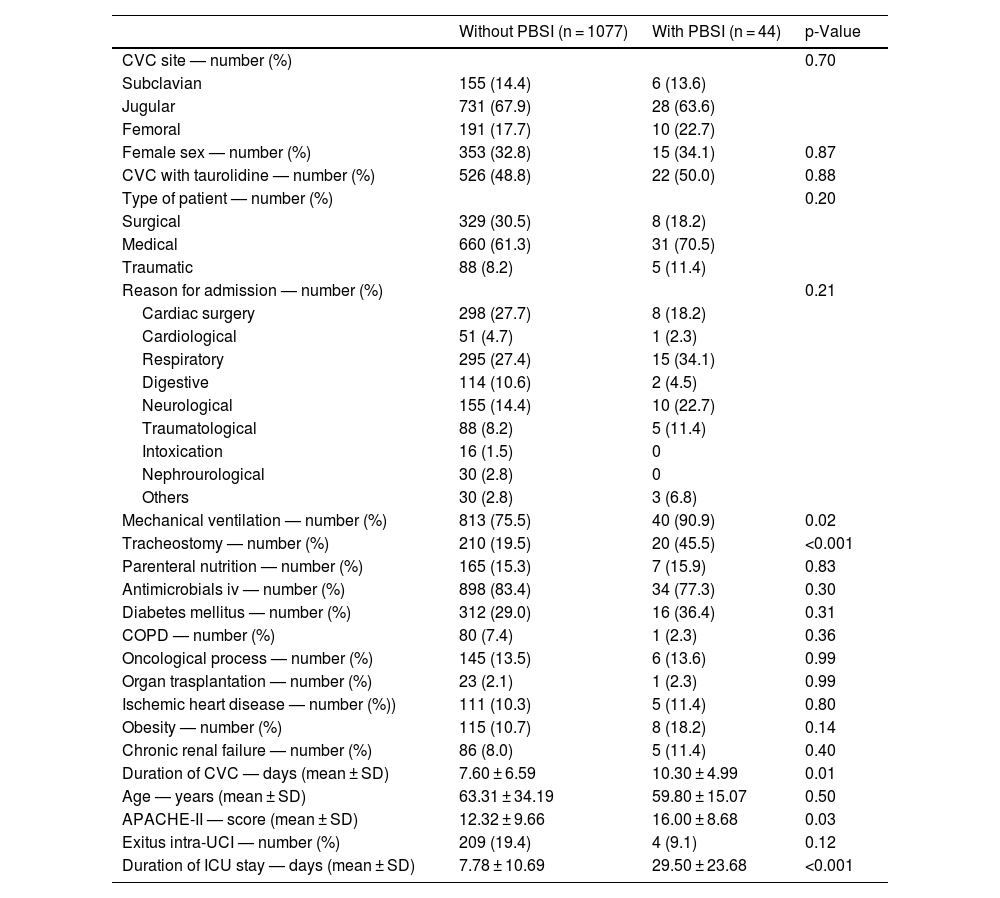

Table 2 shows the comparison of CVCs with and without PBSI. We found that CVCs with PSBI showed a higher rate of mechanical ventilation (p = 0.02) and tracheostomy (<0.001), higher duration of CVC (p = 0.01), higher APACHE-II (p = 0.03), and higher duration of ICU stay (p < 0.001) that CVCs without PBSI. There were not found significant differences between CVCs with and without PBSI on CVC access, sex, taurolidine, type of patient, reason for admission, parenteral nutrition, antimicrobials iv, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, oncological process, organ transplantation, ischemic heart disease, obesity and age.

Characteristics of central venous catheters (CVC) with and without primary bloodstream infection (PBSI).

| Without PBSI (n = 1077) | With PBSI (n = 44) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CVC site — number (%) | 0.70 | ||

| Subclavian | 155 (14.4) | 6 (13.6) | |

| Jugular | 731 (67.9) | 28 (63.6) | |

| Femoral | 191 (17.7) | 10 (22.7) | |

| Female sex — number (%) | 353 (32.8) | 15 (34.1) | 0.87 |

| CVC with taurolidine — number (%) | 526 (48.8) | 22 (50.0) | 0.88 |

| Type of patient — number (%) | 0.20 | ||

| Surgical | 329 (30.5) | 8 (18.2) | |

| Medical | 660 (61.3) | 31 (70.5) | |

| Traumatic | 88 (8.2) | 5 (11.4) | |

| Reason for admission — number (%) | 0.21 | ||

| Cardiac surgery | 298 (27.7) | 8 (18.2) | |

| Cardiological | 51 (4.7) | 1 (2.3) | |

| Respiratory | 295 (27.4) | 15 (34.1) | |

| Digestive | 114 (10.6) | 2 (4.5) | |

| Neurological | 155 (14.4) | 10 (22.7) | |

| Traumatological | 88 (8.2) | 5 (11.4) | |

| Intoxication | 16 (1.5) | 0 | |

| Nephrourological | 30 (2.8) | 0 | |

| Others | 30 (2.8) | 3 (6.8) | |

| Mechanical ventilation — number (%) | 813 (75.5) | 40 (90.9) | 0.02 |

| Tracheostomy — number (%) | 210 (19.5) | 20 (45.5) | <0.001 |

| Parenteral nutrition — number (%) | 165 (15.3) | 7 (15.9) | 0.83 |

| Antimicrobials iv — number (%) | 898 (83.4) | 34 (77.3) | 0.30 |

| Diabetes mellitus — number (%) | 312 (29.0) | 16 (36.4) | 0.31 |

| COPD — number (%) | 80 (7.4) | 1 (2.3) | 0.36 |

| Oncological process — number (%) | 145 (13.5) | 6 (13.6) | 0.99 |

| Organ trasplantation — number (%) | 23 (2.1) | 1 (2.3) | 0.99 |

| Ischemic heart disease — number (%)) | 111 (10.3) | 5 (11.4) | 0.80 |

| Obesity — number (%) | 115 (10.7) | 8 (18.2) | 0.14 |

| Chronic renal failure — number (%) | 86 (8.0) | 5 (11.4) | 0.40 |

| Duration of CVC — days (mean ± SD) | 7.60 ± 6.59 | 10.30 ± 4.99 | 0.01 |

| Age — years (mean ± SD) | 63.31 ± 34.19 | 59.80 ± 15.07 | 0.50 |

| APACHE-II — score (mean ± SD) | 12.32 ± 9.66 | 16.00 ± 8.68 | 0.03 |

| Exitus intra-UCI — number (%) | 209 (19.4) | 4 (9.1) | 0.12 |

| Duration of ICU stay — days (mean ± SD) | 7.78 ± 10.69 | 29.50 ± 23.68 | <0.001 |

COPD = Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; SD = standard deviation.

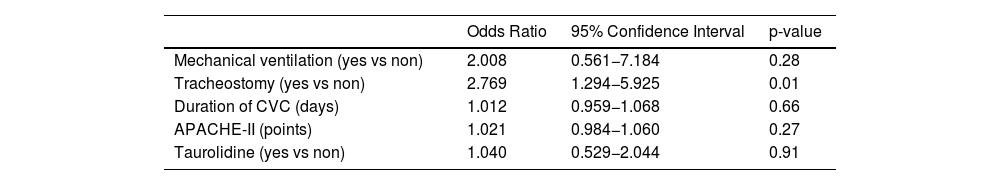

Logistic regression analysis showed an association of tracheostomy with the risk of PBSI; however, we did not find the association of other variables (included taurolidine) with the risk of PBSI (Table 3).

Multiple logistic regression analyses to determine factors associated with Primary Bloodstream Infection.

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical ventilation (yes vs non) | 2.008 | 0.561−7.184 | 0.28 |

| Tracheostomy (yes vs non) | 2.769 | 1.294−5.925 | 0.01 |

| Duration of CVC (days) | 1.012 | 0.959−1.068 | 0.66 |

| APACHE-II (points) | 1.021 | 0.984−1.060 | 0.27 |

| Taurolidine (yes vs non) | 1.040 | 0.529−2.044 | 0.91 |

CVC = central venous catheters; APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation.

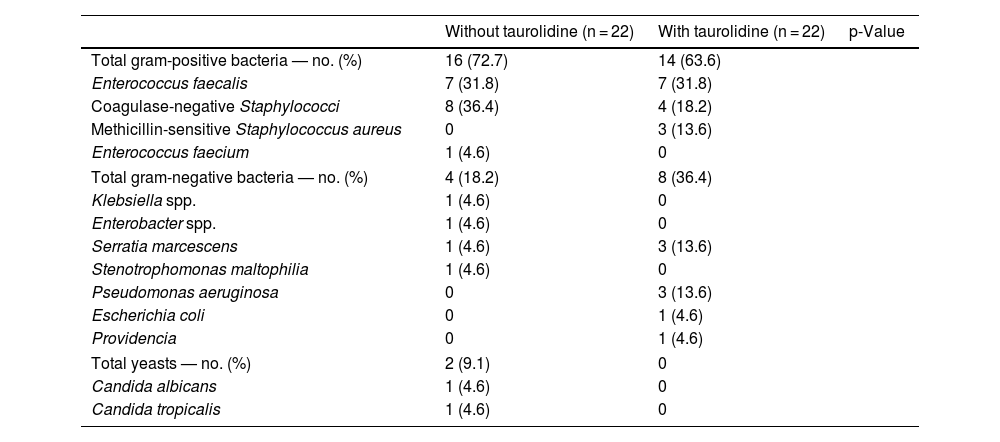

Table 4 shows the microorganisms responsible for PBSI with and without taurolidine. There were not found significant differences in the microorganisms responsible for PBSI between both patient groups (p = 0.18).

Microorganisms responsible of primary bloodstream infection in central venous catheters (CVC) with and without taurolidine.

| Without taurolidine (n = 22) | With taurolidine (n = 22) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total gram-positive bacteria — no. (%) | 16 (72.7) | 14 (63.6) | |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 7 (31.8) | 7 (31.8) | |

| Coagulase-negative Staphylococci | 8 (36.4) | 4 (18.2) | |

| Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus | 0 | 3 (13.6) | |

| Enterococcus faecium | 1 (4.6) | 0 | |

| Total gram-negative bacteria — no. (%) | 4 (18.2) | 8 (36.4) | |

| Klebsiella spp. | 1 (4.6) | 0 | |

| Enterobacter spp. | 1 (4.6) | 0 | |

| Serratia marcescens | 1 (4.6) | 3 (13.6) | |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 1 (4.6) | 0 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 0 | 3 (13.6) | |

| Escherichia coli | 0 | 1 (4.6) | |

| Providencia | 0 | 1 (4.6) | |

| Total yeasts — no. (%) | 2 (9.1) | 0 | |

| Candida albicans | 1 (4.6) | 0 | |

| Candida tropicalis | 1 (4.6) | 0 | |

Previously, it was found in a meta-analysis published by Sun et al. in 2020, including 4 RCTs with 476 CVC, that taurolidine sealing vs control (saline or heparin) in children was associated with lower risk of CRB.14 However, there has been no reported data about CVC associated bacteremia of critically ill adult patients using taurolidine sealing. In our series with 1121 CVC in critically ill adult patients, this beneficial effect of taurolidine sealing compared to saline serum 0.9% sealing was not found.

Different risk factors of CVC associated bacteremia has been reported, such as duration of catheterization, total parenteral nutrition, use of multiple-lumen catheters, length of ICU stay, the position of indwelling, APACHE-II score, age, the extensive use of antibiotic, diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, CVC site and tracheostomy.20–22 However, although some variables were different in comparison between the CVCs that developed or not PBSI in our series, the only variable associated with PBSI in the regression analysis was the presence of tracheostomy.

In addition, some preventive measures have been found to decrease the risk of CVC associated bacteremia, such as antimicrobial-coated CVC,23 chlorhexidine-impregnated dressings,24 antiseptic barrier caps.25 However, we have not been able to evaluate the effect of these measures because all CVCs were clorhexidine impregnated and because we did not use chlorhexidine-impregnated dressings or antiseptic barrier caps.

After the beginning of our study, other interesting studies have been published in respect to the use of locking solution with taurolidine.26–29 In one pre and post study, it was found a reduction of CRB in hemodialysis with the use of locking solution with taurolidine-citrate-heparin.26 In a retrospective case series in children with parenteral nutrition in the home setting, it was found a reduction of CRB with taurolidine.27 In a RCT, it was found a reduction of CRB in hemodialysis catheters with the use of locking solution with taurolidine-heparin.28 However, in a RCT in paediatric oncology patients, the use locking solution with taurolidine-citrate-heparin was not associated with a reduction of CRB.29 However, in none of those recently published studies were reported data about CRB in CVC of critically ill adult patients using taurolidine sealing. Thus, herein lies the novelty of the objective and findings of our study.

We want to admit some limitations of our study. We have not been able to report the CVC indication, number of lumens in each catheter that were not used and how long the lumens have remained unused for each catheter. Besides, the taurolidine or saline serum sealing was not randomized assigned, and we have not reported whether the sealing in each group of patients was carried out adequately. We do not know what the effect would have been using other preventive measures of CVC associated bacteremia. However, taking into account our PSBI rate, it seems appropriate to implement other preventive measures to try to reduce it.

In addition, after the beginning of our study, other interesting in vitro studies have been published in respect to the use of locking solution with taurolidine.30,31 In study one was compared the effectiveness of solutions as different taurolidine concentrations (3.5%, 2%, 1.35% and 0.675%), and it was concluded that 0.675% taurolidine is still effective.30 In another study was concluded that a solution of 1.35% taurolidine is more effective than a solution of 4% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) to eradicate gram-positive and gram-negative microorganisms and fungi.31 However, we only compared the use of locking solution with taurolidine 0.9% and saline serum 0.9%.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting data about the use of sealing of unused lumens of CVCs with taurolidine in critically ill adult patients. In our preliminary study, we have not been able to demonstrate that sealing unused lumens of CVCs with taurolidine can reduce the risk of PBSI in critically ill adult patients. However, it would be interesting to conduct randomized studies that control the aspects discussed in our limitations to confirm or discard our findings.

Key messages- -

Some recent meta-analyses have concluded that sealing unused vascular catheter lumens with taurolidine led to a reduction in catheter-related bacteremia in certain catheters.

- -

Some recent clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) suggested the sealing of unused vascular catheter lumens with taurolidine in certain catheters.

- -

Sealing of unused lumens of CVCs with taurolidine in critically ill adult patients did not reduce the risk of CVC associated bacteremia.

Leonardo Lorente conceived, designed and coordinated the study, participated in acquisition and interpretation of data, and drafted the manuscript. Maria Lecuona, Elena Pérez, Adrián Hernández, Sergio Sánchez, Lucas González, Alejandro Ramos, Jesús Pimentel, Pablo Correa, Carolina Martín, Carmen Dolores Chinea and Ana Madueño participated in acquisition of data. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and made the final approval of the version to be published.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processNone.

FundingNone.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.