Advances in intensive medicine have increased the survival rate of a growing number of patients with chronic critical illness. However, new situations have come up too: post-intensive care syndrome, persistent critical illness, and a population of chronic critically ill patients (CIP) who require intensive care for long periods of time. The latter situation is a condition recently described that challenges the treatments available today and leaves frail patients with little capacity to breath or move adequately.1,2 The common denominator is that they have single organ failure that prevents proper weaning from mechanical ventilation. For a unit like ours, the incidence rate sits at around 6.7% of all patients admitted. The medical literature reports an overall rate between 5% and 8%, 19% in trauma patients, and 40% in septic patients.

These patients are characterized by:3,4

- •

Stays at the intensive care unit (ICU) >15 days.

- •

Dependency of mechanical ventilation (>4 weeks).1

- •

Advanced age.

- •

Evidence of persistent organ dysfunction.

- •

Survival to early aggression, but often recovered not well enough to be discharged from the hospital and sent back home.

This entity is defined by the Persistent Inflammation, Immunosuppression, and Catabolism Syndrome” (PICS)5,6 (Table 1),3 and is characterized by a depressed adaptative immunity, low—but persistent—level of inflammation, diffuse apoptosis, loss of lean mass, and poor scarring-pressure ulcers.

Diagnostic criteria of the Persistent Inflammation, Immunosuppression, and Catabolism Syndrome.

| Clinical-analytical determinants | |

|---|---|

| Persistent | Stay at the ICU setting >14 days |

| Inflammation | CRP >50 μg/dL |

| Immunosuppression | Total lymphocyte count <0.80 × 109/L |

| Catabolism | Weight loss > 10% during hospitalization or BMI <18 |

| CHI < 80% | |

| Albumin levels <3.0 g/L | |

| Prealbumin levels <10 mg/dL | |

| RbP <10 μg/dL |

BMI, body mass index; CHI, creatinine/height index; CRP, C-reactive protein; ICU, intensive care unit; RbP, retinol binding protein.

The overall in-hospital mortality rate of these patients is 31%. This mortality rate is 16%, and 30% in trauma and septic patients, respectively, at the 6-month follow-up. However, this rate can go up to 75% at the 3-year follow-up.

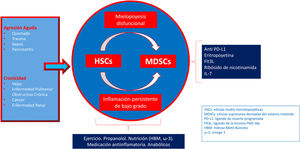

In the management of the PICS complete recovery is almost impossible because from the standpoint of catabolism, the syndrome drains all the energy from the body ultimate reserves. Also, because the immune system panics in response to the aggression and to the different therapies used: the bone marrow releases a large number of immature cells that have mixed effects on the patient causing greater swelling and leaving the organism unprotected with the same efficacy compared to mature cells. From the pathophysiological standpoint, we should consider that emergency myelopoiesis emerges in response to an acute aggression at the expense of less lymphopoiesis and erythropoiesis, which enhances anemia, and lymphopenia. Also, it conditions the expansion—via signal transducer and activation of transcription 3 (STAT3) associated with the cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) promoter—of a heterogeneous population of immature myeloid cells (IMC) with immunosuppressant properties (IP).6Fig. 1 shows the complex scheme of therapeutic approach both of immunosuppression and catabolism.7

From the clinical standpoint, these patients are often ventilator-dependent, and show cerebral dysfunction (delirium), neuromuscular weakness, endocrinopathy (loss of pulsatile secretion of the anterior pituitary, hypogonadism), malnutrition, anasarca, decubitus ulcers, and discomfort (pain, thirst, dyspnea, anxiety, and poor verbal communication due to tracheostomy).

Chronic critical illness is a devastating condition whose mortality rate exceeds that of malignant diseases. In the United States alone, the healthcare costs derived from the management of CIP are over US$200 billion (nearly є18 000 million) and counting.8

We should bear in mind that, on many occasions, to safeguard patients and prevent the collapse of the healthcare personnel at the different hospital floors, ICU discharges are often delayed. This translates into longer ICU stays for clinically stable patients from LOC I, and LOC II groups (Levels of Critical Care. ESCIM-Level of Care. 2011). Also, they need constant care from the nursing team (routine postural changes, complex healing procedures, repeated lab tests, strict control of hydric balance, aspiration of secretions, etc.) that often exceed the capabilities of a conventional hospital ward. Although these patients are often physiologically stable, they are still exposed to complications associated with their primary diagnosis, as well as to subsequent organ failures due to the interrelations among sepsis, immune function, and nutritional status. This means that they need to be transferred to a different more friendly environment with a more suitable doctor/nurse ratio (lower actually) where all nutritional, rehabilitation, and psychological needs are duly met; we should mention that these units—necessarily cross-sectional—should be led by specialists in intensive medicine.

All these aspects have sparked interest in specific units for less severe critically ill patients as a bridging therapy between the level of care provided at the ICU setting and at a conventional hospital floor, which, in turn, is an opportunity to create more modern, efficient, and human structures.9 They should be transferred to chronic units in centers specialized in the management of these patients (long-term acute care) including the possibility of continuous monitorization: ECG, SpO2, and non-invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring. Nurse control through telemetry and alarms, mechanical ventilators, BiPAP ventilation, and different ventilation accessories and consumables facilitate the weaning process from the ventilator. Rehabilitation equipment for chronic patients, electrostimulation, bicycles, spirometers, physical therapists—including respiratory physical therapists—rehabilitators, psychologists, and nutritionists, added to a friendly setting for the proper physical and mental rehabilitation increase the patient’s autonomy, humanization, palliative care, and the social, and familial perspective.10

Please cite this article as: García-de-Lorenzo A, Añón JM, Asensio MJ, Burgueño P. Enfermedad crítica crónica ¿cómo abordarla? Med Intensiva. 2022;46:277–279.