To describe and characterize a cohort of octogenarian patients admitted to the ICU of the University Central Hospital of Asturias (HUCA).

DesignRetrospective, observational and descriptive study of 14 months’ duration.

SettingCardiac and Medical intensive care units (ICU) of the HUCA (Oviedo).

ParticipantsPatients over 80 years old who were admitted to the ICU for more than 24 h.

InterventionsNone.

Main variables of interestAge, sex, comorbidity, functional dependence, treatment, complications, evolution, mortality.

ResultsThe most frequent reasons for admission were cardiac surgery and pneumonia. The average admission stay was significantly longer in patients under 85 years of age (p = 0,037). 84,3% of the latter benefited from invasive mechanical ventilation compared to 46,2% of older patients (p = <0,001). Patients over 85 years of age presented greater fragility. Admission for cardiac surgery was associated with a lower risk of mortality (HR = 0,18; 95% CI (0,062–0,527; p = 0,002).

ConclusionsThe results have shown an association between the reason for admission to the ICU and the risk of mortality in octogenarian patients. Cardiac surgery was associated with a better prognosis compared to medical pathology, where pneumonia was associated with a higher risk of mortality. Furthermore, a significant positive association was observed between age and frailty.

Describir y caracterizar una cohorte de pacientes octogenarios ingresados en la UCI del Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias (HUCA).

DiseñoEstudio retrospectivo, observacional y descriptivo de 14 meses de duración.

ÁmbitoUnidad de Cuidados Intensivos (UCI) Cardíaca y UCI Polivalente del Servicio de Medicina Intensiva del HUCA (Oviedo).

ParticipantesPacientes mayores de 80 años que ingresaron en la UCI durante más de 24 horas.

IntervencionesNinguna.

Variables de interés principalesEdad, sexo, comorbilidad, capacidad funcional, tratamiento, complicaciones, evolución, mortalidad.

ResultadosLos motivos de ingreso más frecuentes fueron la cirugía cardíaca y la neumonía. La estancia media de ingreso fue significativamente mayor en pacientes menores de 85 años (p = 0,037). El 84,3% de éstos últimos se benefició de ventilación mecánica invasiva frente al 46,2% de los pacientes más mayores (p = <0,001). Los pacientes mayores de 85 años presentaron mayor fragilidad. El ingreso por intervención quirúrgica cardíaca se asoció con menor riesgo de mortalidad (HR = 0,18; IC 95% (0,062–0,527; p = 0,002).

ConclusionesLos resultados muestran una asociación entre el motivo de ingreso en UCI y el riesgo de mortalidad en pacientes octogenarios. La cirugía cardíaca se asoció con mejor pronóstico frente a la patología médica, donde la neumonía se asoció con mayor riesgo de mortalidad. Además, se observó una asociación positiva significativa entre edad y fragilidad.

The remarkable increase in life expectancy since the mid-20th century resulting from the demographic transition and technological and medical advances has triggered a growth in the world's population. Predictions for the year 2050 suggest that the world’s population will reach 9.8 billion people,1 leading to population aging, especially in industrialized countries, where the population older than 65 is growing at a faster rate vs other population segments. In Spain, the current life expectancy is 83.3 years, one of the highest worldwide.2 This increased life expectancy is considered a success in public health, but also triggers more chronic diseases, functional limitations, frailty, and dependency, posing a new health care challenge that will result in greater use of beds and resources at the intensive care unit (ICU) setting.3 In this regard, we should introduce the concept of frailty, a clinical–biological syndrome characterized by changes primarily at the endocrine level that result in fewer physiological reserves, sarcopenia, anemia, and dysregulation of the immune system,4,5 leading to increased vulnerability to various diseases or stressors.6 Therefore, ICU admission is a relevant issue that should not be based solely on age but take into consideration other criteria such as the patient's previous functional status, diagnosis at admission, or comorbidities.7–9 Until now, prognostic scales have been studied to evaluate the severity of the patient at the ICU admission (APACHE II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Disease Classification System II, and SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment), and others such as the Barthel index,10 the Charlson comorbidity index,11 and the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS), or the modified Rockwood scale,12 which consider frailty as a fundamental factor in the patient's prognosis.

On the other hand, the application of fundamental bioethical principles (autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice) guarantees adequate care for seriously ill patients. Respecting the right to care for all patients is essential to fulfilling the ethical principle of justice, which is based on 2 fundamental premises: 1) “all individuals, by virtue of being human, have the same dignity, regardless of any circumstance, and therefore deserve equal consideration and respect,” 2) “efforts should be made to ensure a fair and equitable distribution of the always limited health care resources to achieve maximum benefit in the community, avoiding inequalities in health care.”13 Based on these premises, age should not be a factor influencing the denial of care or the limitation of resources used in treatment. However, the health crisis experienced during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic triggered a scenario that separated from the routine clinical practice, in which resources were scarce to meet the high volume of patients, putting the entire health care system to the test.14 In fact, in Spain, the General Council of Official Medical Colleges (CGCOM) proposed a series of controversial recommendations with age as a fundamental factor in admitting a patient to the ICU.15

In recent years, several studies have been conducted on elderly patients admitted to the ICU, most with heterogeneous criteria in terms of design and methodology used and with considerable variability regarding age and cutoff points to define age groups, admission criteria, types of hospitals, and ICUs. Examples of this are the studies conducted by Fuchs et al.16 or Pietiläinen et al.,17 which focus on aspects such as survival of elderly patients, ICU-related mortality and morbidity, or issues associated with the admission or non-admission of elderly patients to these units. Back in 2020, Escudero-Acha et al.18 published a scientific letter in Medicina Intensiva analyzing the impact that the variable age per se has in decisions of preventing the admission of a patient to the ICU as a way of limiting life-sustaining treatments over a period of time outside the pandemic. As a result of this study, it was observed that, in 31% of the cases, age along with other variables accounted for the non-ICU admission of these patients. However, the scientific medical literature currently available is contradictory. Some articles state that age is not associated solely with worse outcomes in patients admitted to the ICU,17,19 while others find age to be an independent risk factor.16 In 2018, in their first research, Pietiläinen et al.19 studied the association of pre-morbid functional status and 1-year outcomes and functional recovery after admission in patients older than 80 years admitted to the ICU. It was observed that a poor pre-morbid functional status doubled the probability of death at 1 year. Four years later, they published a new study17 with older patients (≥85 years). In this case, the hypothesis that adding the patients’ previous functional status to their standard prediction models including age, sex, type of admission, and disease severity significantly improved the discriminatory capacity of the model, as well as its ability to predict the 1-year mortality rate.

Based on this, it seems important to strive for the development of appropriate prognostic models that can accurately predict the outcome of these patients since, in most cases of one-year survival, a full functional recovery has been demonstrated.17,19 Therefore, our objective was to describe the characteristics and prognosis of patients over 80 years old admitted to our ICU, conducting a comparative analysis by age subgroups and length of stay in the ICU and analyzing patient mortality outcomes in relation to their previous functional status and age.

MethodsThis was an observational, descriptive, and retrospective study with a cohort of elderly patients (≥80 years) who required admission for more than 24 h in the ICU of HUCA, Oviedo, Spain from October 24, 2020 through December 31, 2021. Patients younger than 80 years, those with hospital stays under 24 h, readmitted ICU patients, those admitted for palliative care, or patients associated with organ donation-oriented care were all excluded from the study. Patients in whom the data collection protocol could not be completed due to a lack of information in their electronic health records were also excluded. Follow-up was conducted 1 year after the admission date through periodic assessments at the health center.

Demographic variables such as age, sex, previous comorbidities, type of patient (medical, coronary, surgical, or trauma), and frailty scales (Barthel index, Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) (see Annex 1 in Supplementary material)) and severity at admission (APACHE II and Glasgow Coma Scale), the ICU stay, and need for mechanical therapies (ventilation or extrarenal depuration) were analyzed. The in-ICU and in-hospital mortality rates were also studied.

To determine the age of patients included in this study, existing literature on elderly ICU patients was reviewed to identify those who may benefit from intensive treatment and search for tools to determine their frailty and outcomes. A wide range of cutoff points around 65, 80, 85, or 90 years were found. It was established that patients older than 80 years would be included in our study, as they were already considered elderly.7 A comparative cutoff was made for subgroups at 85 years, representative of life expectancy in Spain2 and the mean age of our cohort. Additionally, participants were categorized into 2 groups based on their CFS scores: robust or pre-frail (<4) and frail (>4), as advised in former studies.22

The information was collected analyzed using the R program (version 4.1.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Data were expressed as mean [standard deviation (SD)] and median [interquartile range (IQR)] for normally distributed and non-normally distributed quantitative variables, respectively, and percentages for categorical variables. Patients younger than 85 years and those ≥85 years were compared using the Student's t-test, or the Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. Multivariate analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazards model to study the association between the 1-year mortality relative since discharge and variables such as age, sex, length of stat, length of ICU stay, and valvular heart disease. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The study was evaluated and approved by HUCA Research Ethics Committee (approval no. 2022.438, Oviedo, Spain), and research was conducted following the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki.

ResultsOut of 2749 patients admitted to the ICU during the study period, 150 (5.46%) were ≥80 years. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 90 patients (3.27% of total admissions) were analyzed.

Demographic resultsFirstly, Table 1 details the baseline, demographic, and clinical characteristics of the study patients. The age range was 81–93 years, with a mean of 84.7 ± 2.9 years, with the under-85-year-old group being the majority (n = 52; 57.8%) vs those ≥85 years (n = 38; 42.2%). A total of 66.7% were men and 33.3%, women. We should mention that 88% of the patients had some cardiovascular risk factor, having been diagnosed 75% of the patients diagnosed with a previous heart disease. Elevated values were obtained in the APACHE severity scale and the Charlson comorbidity index. Regarding frailty assessed by the CFS scale, the median value was 3 (non-frailty). In over half of the cases, surgery was the reason for admission (n = 46; 51.1%), mainly scheduled cardiac surgery (n = 35; 38.9%), followed by pneumonia (n = 16; 17.8%) and hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke (n = 7; 7.8%). The mean overall length of stay was 16.2 + 11.9 days. A total of 22.2% of the patients died during admission.

General characteristics of the overall study population.

| Demographic characteristics | All | Severity and frailty scales at admission | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (mean, (SD)) | 84.7 (2.9) | Glasgow (median [IQR]) | 15.0 [15.0, 15.0] |

| Sex = Female (n (%)) | 30 (33.3) | CFS (median [IQR]) | 3.0 [3.0, 4.0] |

| Length of stay (days) (mean, (SD)) | 16.2 (11.9) | APACHE (median [IQR]) | 16.0 [13.2, 18.0] |

| Length of ICU stay (days) (mean, (SD)) | 6.8 (8.6) | Charlson (median [IQR]) | 6.0 [5.0, 8.0] |

| Death (Length of stay) | 20 (22.2) | IABVD (n (%)) | 79 (87.8) |

| Death at the ICU setting (n (%)) | 15 (16.7) | Therapeutic measures at the ICU setting | |

| Cardiovascular risk factors (n (%)) | 79 (87.8) | NIMV (n (%)) | 4 (4.4) |

| Arterial hypertension (n (%)) | 63 (70.0) | IMV (n (%)) | 61 (67.8) |

| Diabetes mellitus (n (%)) | 23 (25.6) | Time on mechanical ventilation (mean (SD)) | 4.0 (8.4) |

| Dyslipidemia (n (%)) | 47 (52.2) | Catecholamines (n (%)) | 53 (58.9) |

| Smoking (n (%)) | 38 (42.2) | Hemodialysis (n (%)) | 2 (2.2) |

| Comorbidities (n (%)) | Transfusion (n (%)) | 24 (26.7) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 22 (24.4) | Number of RBC concentrates (mean (SD)) | 0.6 (1.8) |

| Chronic lung disease | 20 (22.2) | Complications (n (%)) | |

| COPD | 7 (7.8) | Intestinal obstruction | 2 (2.2) |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | 2 (2.2) | Intestinal ileus | 6 (6.7) |

| OSA | 2 (2.2) | Kidney failure | 22 (24.4) |

| Asthma | 6 (6.7) | Renal failure | 2 (2.2) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 68 (75.6) | Heart failure | 8 (8.9) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 24 (26.7) | Arrhythmias | 35 (38.9) |

| Valvular disease | 45 (50.0) | Delirium/Confusional syndrome | 20 (22.2) |

| Heart failure | 25 (27.8) | Infections | 26 (28.9) |

| Arrythmias | 38 (42.2) | Electrolyte imbalance (Na+) | 11 (12.2) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 13 (14.4) | Electrolyte imbalance (K+) | 28 (31.1) |

| Liver disease | 3 (3.3) | Pneumothorax | 5 (5.6) |

| Neoplasm | 30 (33.3) | Tracheostomy | 7 (7.8) |

| Solid neoplasm | 23 (25.6) | Course of the disease (n (%)) | |

| Hematological disease | 7 (7.8) | Life support limitation | 11 (12.2) |

| Neurodegenerative disease | 9 (10.0) | Respiratory rehabilitation | 19 (21.1) |

| Musculoskeletal disease | 40 (44.4) | Motor rehabilitation | 24 (26.7) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 1 (1.1) | ICU readmission | 4 (4.4) |

| Neurovascular disease | 14 (15.6) | Destination (n (%)) | |

| Type of patient (n (%)) | Home | 38 (42.2) | |

| Medical | 40 (44.4) | Home with caregiver | 19 (21.1) |

| Surgical | 46 (51.1) | Death | 19 (21.1) |

| Trauma | 4 (4.4) | Another hospital | 8 (8.9) |

| Characteristics ad admission | Nursing home | 6 (6.7) | |

| Another hospital center | 25 (27.8) | Death (1-year follow-up) | 26 (28.9) |

| Hospital ward | 14 (15.6) | ||

| Scheduled | 28 (31.1) | ||

| Emergency | 23 (25.6) |

APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; CFS, Clinical Frailty Scale; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IABVD, Independent for Activities of Daily Living; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; IQR, interquartile range; NIMV, non-invasive mechanical ventilation; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; RBB, red blood cell; SD, standard deviation; UCI, Intensive Care Unit.

When comparing patients by age subgroups, we saw that the under-85-years group had a mean longer length of stay, both in the hospital and at the ICU vs the ≥85 year-group (Table 2). While the younger group had a mean ICU stay of 8.4 ± 8.9 days, the older group was admitted to the ICU for a mean of 4.6 ± 7.8 days, with statistically significant differences (P = 0.037). A total of 84.3% of the patients younger than 85 years benefited from invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) vs 46.2% of the older patient group (P < 0.001), with significantly longer IMV time in the younger group. Similarly, it was in this latter group where vasoactive drugs were used more frequently. Another statistically significant difference found in this age-group segmented analysis was frailty in both age groups measured with the CFS scale. Greater frailty was observed in the group of patients ≥85 years. Additionally, in this older age group, there was a higher prevalence of solid neoplasms on admission and neuromuscular diseases.

Characteristics of patients by age subgroup (< 85 years vs ≥ 85 years).

| < 85 years | ≥ 85 years | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 52 (57.7%) | N = 38 (42.2%) | ||

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age (years) (mean, (SD)) | 19 (37.3) | 11 (28.2) | 0.498 |

| Sex = Female (n (%)) | 17.8 (10.3) | 14.1 (13.5) | 0.141 |

| Length of stay (days) (mean, (SD)) | 8.4 (8.9) | 4.6 (7.8) | 0.037 |

| Length of ICU stay (days) (mean, (SD)) | 14 (27.5) | 6 (15.4) | 0.268 |

| Death (Length of stay) | 11 (21.6) | 4 (10.3) | 0.254 |

| Therapeutic measures at the ICU setting | |||

| NIMV (n (%)) | 2 (3.9) | 2 (5.1) | 1.000 |

| IMV (n (%)) | 43 (84.3) | 18 (46.2) | <0.001 |

| Time on mechanical ventilation (mean (SD)) | 5.7 (9.4) | 1.8 (6.5) | 0.029 |

| Catecholamines (n (%)) | 36 (70.6) | 17 (43.6) | 0.018 |

| Hemodialysis (n (%)) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.6) | 1.000 |

| Transfusion (n (%)) | 14 (27.5) | 10 (25.6) | 1.000 |

| Number of RBC concentrates (mean (SD)) | 0.7 (2.1) | 0.5 (1.1) | 0.621 |

| Comorbidities (n (%)) | |||

| Alcohol consumption | 9 (17.6) | 13 (33.3) | 0.142 |

| Chronic lung disease | 11 (21.6) | 9 (23.1) | 1.000 |

| COPD | 5 (9.8) | 2 (5.1) | 0.672 |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.1) | 0.361 |

| OSA | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.6) | 1.000 |

| Asthma | 3 (5.9) | 3 (7.7) | 1.000 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 36 (70.6) | 32 (82.1) | 0.314 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 10 (19.6) | 14 (35.9) | 0.136 |

| Valvular disease | 26 (51.0) | 19 (48.7) | 1.000 |

| Heart failure | 16 (31.4) | 9 (23.1) | 0.527 |

| Arrythmias | 20 (39.2) | 18 (46.2) | 0.656 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 5 (9.8) | 8 (20.5) | 0.259 |

| Liver disease | 2 (3.9) | 1 (2.6) | 1.000 |

| Neoplasm | 14 (27.5) | 16 (41.0) | 0.259 |

| Solid neoplasm | 8 (15.7) | 15 (38.5) | 0.027 |

| Hematological disease | 6 (11.8) | 1 (2.6) | 0.223 |

| Neurodegenerative disease | 2 (3.9) | 7 (17.9) | 0.065 |

| Musculoskeletal disease | 23 (45.1) | 17 (43.6) | 1.000 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Neurovascular disease | 4 (7.8) | 10 (25.6) | 0.044 |

| Severity and frailty scales at admission | |||

| Glasgow (median [IQR]) | 15.0 [15.0, 15.0] | 15.0 [15.0, 15.0] | 0.708 |

| CFS (median [IQR]) | 3.0 [2.0, 4.0] | 4.0 [3.0, 5.0] | 0.016 |

| APACHE (median [IQR]) | 16.0 [14.0, 18.0] | 16.0 [12.0, 19.5] | 0.624 |

| Charlson (median [IQR]) | 6.0 [5.0, 7.0] | 6.0 [5.5, 8.0] | 0.078 |

| IABVD (n (%)) | 48 (94.1) | 31 (79.5) | 0.076 |

APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; CFS, Clinical Frailty Scale; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IABVD, Independent for Activities of Daily Living; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; IQR, interquartile range; NIMV, non-invasive mechanical ventilation; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; RBB, red blood cell; SD, standard deviation; UCI, Intensive Care Unit.

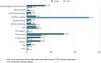

Regarding the reason for admission, as shown in Fig. 1, younger patients were primarily admitted for cardiac surgery and pneumonia (43.1% and 27.5%, respectively). Of the 14 patients admitted for pneumonia, 13 were specifically diagnosed with COVID-19 related pneumonia. In the ≥85 year-group, cardiac surgery accounted for a third of all admissions, being again the most frequent, followed by acute pulmonary edema or arrhythmias and stroke, each accounting for 12.8% of admissions. In this subgroup of patients, 2 admissions due to pneumonia were reported, one of which was diagnosed with COVID-19 related pneumonia.

Results according to the length of stay and the CFS scaleAdditionally, an independent analysis of age and sex was conducted, based on whether the length of stay was longer or shorter than 30 days, with only 3 patients exceeded 1 month of admission. When patients with long lengths of stay were analyzed, statistically significant differences were found in the days they were on IMV (37 days vs 2.9 days in patients with stays < 30 days; P < 0.001).

A comparative analysis was also performed considering the score obtained in the CFS frailty scale, categorizing patients as robust or pre-frail (CFS < 4) and frail (CFS > 4). In patients with a CFS score ≤ 4, the mean age was 84.2 ± 2.7 years vs 86.5 ± 3.2 years in patients with CFS score > 4 (P = 0.002). A total of 97.2% of the patients (n = 69) with a CFS score ≤ 4 were self-sufficient regarding activities of daily living, whereas in the frail patient group, only 52.6% (n = 10) were self-sufficient patients. Preexisting comorbidities in both groups were distributed homogeneously, except for chronic kidney disease, present in 31.6% of frail patients vs 9.9% of patients with CFS < 4. The most common reason for admission in frail patients was a medical or traumatic cause, while in the non-frail group, the most common reason for admission was surgery, mainly scheduled cardiac surgery (42.3%). With similar clinical management and no differences in complications, the rate of deceased patients was 25.4% (n = 18) in non-frail patients and 10.5% (n = 2) in frail patients.

Results based on mortalityFinally, when comparing the different characteristics of deceased patients vs survivors, longer ICU stays were reported in the former group (10.7 + 11.1 days vs 5.2 + 6.8 days, respectively). We should also mention that medical pathology was a significantly major reason for admission in the deceased group (69.2%) vs surgical or traumatic reasons, which accounted for 23.1% and 7.7%, respectively. The bar chart shown in Fig. 2 illustrates living and deceased patients based on their reason for admission, offering a visual comparison between these 2 variables. We can see how pneumonia was the most common reason for admission in the deceased group (30.8%) vscardiac surgery, which represented the main reason for admission in discharged patients (51.6%) (P = 0.008).

Additionally, a lower GCS score at admission was seen in patients who eventually died (GCS deceased = 12 ± 4.60 vs GCS survivors = 14.42 ± 2.40). Regarding comorbidities, we found that heart disease was present in 84.4% of survivors vs 53.8% of deceased patients with this comorbidity at admission (P = 0.005), showing valvular heart disease the most significant difference: 60.9% of survivors had some valvular heart disease vs 23.1% of deceased patients (P = 0.002). Significant differences were also found in in-ICU complications, particularly regarding infections. A total of 53.8% of deceased patients developed some type of infection during their ICU stay, while this complication occurred in 18.8% of survivors (P = 0.002). Furthermore, it was observed that deceased patients received IMV for a longer period of time than the group of surviving patients.

Multivariate analysisIn the multivariate analysis represented in Table 3, a long length of ICU stay was observed as an independent variable associated with mortality. On the other hand, the presence of valvular heart disease was associated with a reduced risk of mortality (HR, 0.18; 95%CI, 0.062—0.527; P = 0.002).

DiscussionThe aging population and advancements in medical-surgical treatments have led to more older individuals being admitted to hospitals, raising questions on the appropriateness of implementing therapeutic measures at the ICU setting. Despite greater knowledge on the progression of these patients and their potential complications, there is no clear evidence regarding ICU admission criteria, which emphasizes the importance of clinical judgment in each individual case. Recently, the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has intensified this debate and raised concerns on whether age as a criterion for rejecting ICU admission is, or not, appropriate.20

Our main finding is that elderly patients admitted for scheduled cardiac surgical procedures have higher survival rates than those admitted for medical reasons (69.2% in the deceased group), likely due to these patients being preselected based on their baseline condition and postoperative recovery capacity. Comparing our results with other studies such as the one conducted by Heyland et al.23 and the mortality analysis by Fuchs et al., notable differences can be noted. They suggest age should be considered an independent mortality risk factor in patients older than 75 years. However, in our age subgroup mortality analysis, we found a mortality rate of 15.4% in patients ≥85 years vs 27.5% in patients younger than 85 years. These differences may be explained by the uneven distribution of the leading cause of mortality, pneumonia (30.8% of deceased patients), which accounted for only 5.1% of admissions in the ≥85 year-group.

When data on the therapeutic measures adopted during the ICU admission were analyzed by age group, we found that 84.3% of the patients from the younger group (<85 years) benefited from IMV while 70.6% required vasoactive drug administration vs 46.2% and 43.6%, respectively, from the older group (≥85 years). Statistically significant differences were reported indicating greater in-ICU resource use in patients younger than 85 years due to their admission reasons inherently requiring more of these measures, or simply because there was treatment adaptation based on a judgment of therapeutic futility and treatment plan. These findings are consistent with those from former studies demonstrating that older patients receive lower intensity in cardiocirculatory, renal, or respiratory therapies.16,24

On the other hand, the relationship between frailty and mortality has been studied by authors such as Silva Obregón25 who reported higher 1-year mortality rates in frail elderly ICU patients, defined as those with a CFS ≥ 5. Another related study, the FRAIL-ICU clinical trial,21 conducted in Spain, aimed to estimate frailty prevalence in ICU patients in Spain and its impact on both in-ICU and 1- and 6-month mortality rates. This trial confirmed the association between frailty and mortality. However, on univariate analysis comparing frail vs non-frail individuals, they performed a specific classification in the elderly (65–80 years) and very elderly (≥80 years), in which no significant differences were found regarding the incidence of frailty, or in other variables, except for comorbidity. Both studies agree that the frailest patients have a higher mortality rate. However, our study found an association between age and frailty, being older patients frailer, yet frail patients with a CFS ≥ 5 had lower mortality rates. This suggests that frailty is more related to mortality than age itself, which underscores its importance in identifying patients who would benefit most from critical care.26 Therefore, there are authors who recommend routinely assessing the CFS scale in elderly critically ill patients due to its good ability to obtain a comprehensive approach prior to admission.27

Limitations of our study include its retrospective and single-center design, its small sample size limiting generalizability, coincidence with the end of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, and exclusion bias of patients admitted for <24 h and potentially severe cases, as well as ICU readmitted patients. Additionally, there may be a survival bias when analyzing patients who have already undergone a selection process by health care professionals. Additionally, the decisions made on the limitation of life-sustaining treatments were not recorded.

This study allows us to understand the current situation, compare it with other published studies (Annex 2 in Supplementary material), and raise awareness on the importance of the comprehensive assessment of elderly patients prior to their admission. There is a lack of consensus and discordance in the scientific medical literature available to this date on the suitable prognostic scales that should be considered when deciding the admission of elderly patients to the ICU setting.17,28,29 Additionally, more studies are needed to define how decisions to limit life support techniques affect the outcomes of elderly patients.30,31 This would allow us to study the non-admission decisions and see if they are associated, or not, with prognostic factors associated with higher mortality rates. It would be here where the hypothetical comprehensive pre-admission assessment scale for elderly patients in the ICU setting would have greater utility and could be used to assist decision-making.

In conclusion can say that the survival of patients older than 80 years selected for ICU admission is not negligible, and those admitted for scheduled cardiac procedures have higher survival rates vs those admitted for medical reasons. In our study, no correlation was seen between frailty measured by the CFS scale and mortality.

Authors’ contributionsStudy design and supervision: R. Rodríguez-García and C. Palomo Antequera. Data collection: L. González-Lamuño and M. Santullano.

Data analysis: B. Martín-Carro and JL. Fernández-Martín.

Manuscript drafting: R. Rodríguez-García, C. Palomo Antequera, L. González-Lamuño, M. Santullano, B. Martín-Carro, and JL. Fernández-Martín.

Manuscript review and editing: all authors.

FundingNone declared.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.