Midazolam is a benzodiazepine still routinely used in Intensive Care Units (ICUs) for the sedation of ventilated patients.1 As a short-acting and potent drug that causes less hemodynamic instability, it could be the ideal sedative if it weren't for its significant cumulative power due to its pharmacokinetics. This is due to its liposolubility and large volume of distribution, which is exacerbated in obese patients with hepatic and/or kidney failure.

Midazolam is hydroxylated by CYP3A4 into hydroxymidazolam, which is pharmacologically less active than the original drug. Between 50% and 70% of midazolam is excreted in the urine within the next 24 h as hydroxymidazolam. Due to its hepatic metabolism, liver failure also affects its metabolism. Similarly, in patients with kidney disease, midazolam elevates the concentrations of hydroxymidazolam, thus leading to an increased pharmacological activity. Therefore, it can cause oversedation during its use,2 takes longer to be eliminated, and withdrawal symptoms are common.

Additionally, there are times that we are not aware of the doses administered in continuous infusion. For example, a dose of midazolam at 10 mg per hour involves a daily dose of 240 mg, 480 mg in 2 days, or 1200 mg every 5 days, which is equivalent to 80 vials of 15 mg or 240 vials of 5 mg.

Comparative studies between midazolam and other hypnotics, such as propofol or isoflurane, as well as studies comparing benzodiazepine and non-benzodiazepine sedation, conclude that it is advisable to avoid benzodiazepines in critically ill patients because their use is associated with delayed awakening and extubation, longer mean ICU and hospital lengths of stay, a higher risk of delirium and cognitive dysfunction,3 and increased mortality.4,5 This has led to the latest international clinical practice guidelines to discourage the use of benzodiazepines and, specifically, midazolam infusions.6

Despite the scientific evidence and recommendations published, the use of midazolam in critically ill patients is still widespread.1 The reasons for this are multiple: lack of an internal working group leading the paradigm shift, resistance to modifying year-long established routine clinical practices, or the convenience of using a single midazolam infusion as a hypnotic. Midazolam is also used to sedate hemodynamically compromised patients because it causes less hypotension, and there is no solid evidence in specific populations of critically ill patients. A retrospective study conducted by Sherer et al. showed higher midazolam-related mortality rates compared to propofol in patients with cardiogenic shock.7

Proper monitoring is essential to prevent oversedation, especially in patients with deep sedation and neuromuscular blockers, in whom continuous electroencephalographic devices should be used. However, despite proper monitoring, the pharmacokinetic characteristics of midazolam, with a longer half-life than propofol or isoflurane and greater cumulative power, do not stop the patient from taking longer to awaken once sedation has been withdrawn. In fact, deep sedation with benzodiazepines has a higher risk of post-extubation delirium than sedation with other drugs.8

There are cases, and these are not exceptional cases, where after days of midazolam infusion and an attempt to switch to shorter-acting drugs for dynamic sedation or awaken for invasive mechanical ventilation weaning, these patients end up not waking up for days. It becomes difficult to distinguish the effect of midazolam from acquired brain injury.9 These patients end up undergoing imaging modalities, electroencephalograms, and/or flumazenil administration.

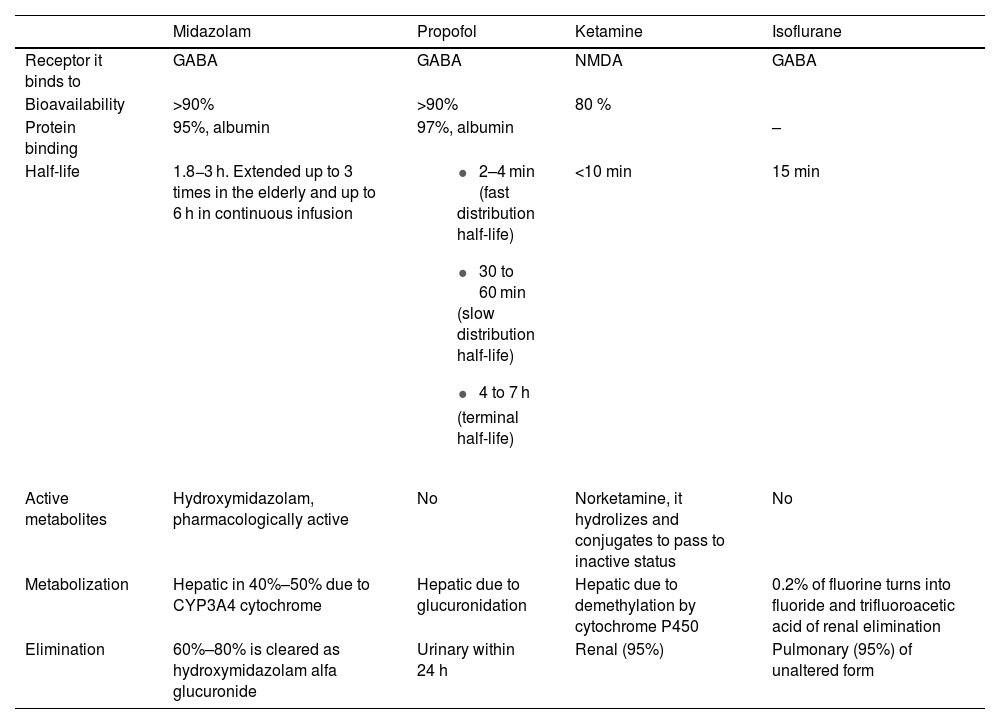

Currently, regarding the established indications of moderate or deep sedation, various alternatives have become available to benzodiazepine sedation, such as propofol, ketamine, or inhalation sedation with isoflurane10 (Table 1). These drugs allow for effective sedation without organ accumulation and a quick awakening time, thus avoiding the drawbacks of midazolam sedation.

Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of hypnotics used for moderate and deep sedation at the ICU setting.

| Midazolam | Propofol | Ketamine | Isoflurane | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receptor it binds to | GABA | GABA | NMDA | GABA |

| Bioavailability | >90% | >90% | 80 % | |

| Protein binding | 95%, albumin | 97%, albumin | – | |

| Half-life | 1.8−3 h. Extended up to 3 times in the elderly and up to 6 h in continuous infusion |

| <10 min | 15 min |

| Active metabolites | Hydroxymidazolam, pharmacologically active | No | Norketamine, it hydrolizes and conjugates to pass to inactive status | No |

| Metabolization | Hepatic in 40%–50% due to CYP3A4 cytochrome | Hepatic due to glucuronidation | Hepatic due to demethylation by cytochrome P450 | 0.2% of fluorine turns into fluoride and trifluoroacetic acid of renal elimination |

| Elimination | 60%–80% is cleared as hydroxymidazolam alfa glucuronide | Urinary within 24 h | Renal (95%) | Pulmonary (95%) of unaltered form |

Benzodiazepines should be limited in our routine clinical practice in the management of critically ill patients. Via enteral administration, they can be indicated for alcohol withdrawal and alcoholic delirium tremens prevention. Via IV bolus administration benzodiazepines can be indicated for procedural hypnosis, acute control of epileptic status, or emergency control of psychomotor agitation with risk to the patient or staff, when pain is not the cause. Via continuous IV infusion, residual indications should be for end-of-life comfort provision and the management of intracranial hypertension when propofol, ketamine, or isoflurane are ill-advised.

Sedation at the ICU setting should not only be used to provide comfort to critically ill patients, but also to prevent post-ICU stay syndrome, while making sure that patients remain in their best possible clinical condition after ICU discharge, avoiding additional safety problems such as delirium or oversedation. This also allows for an efficient management of ICU beds, thus facilitating the admission of other critically ill patients and humanizing clinical care by facilitating patient-family-health care provider interactions.

Several studies support that non-benzodiazepine sedation regimens are more cost-effective than benzodiazepine regimes, despite the lower acquisition cost of the latter. This overall cost reduction is likely due to a shorter duration of mechanical ventilatory support (MVS) and ICU length of stay thanks to the use of non-benzodiazepine sedatives, including inhalation sedation.

In conclusion, shorter ICU stays, more bed availability, improved patient function after ICU discharge, and lower overall costs per patient make the choice of sedatives for our patients a fundamental aspect of their management. And midazolam infusion during MVS does not favor any of these premises.