Benzodiazepines, mainly represented by midazolam, are and have been the sedatives most widely used in the last 30 years in critically ill patients.1 However, their relationship with delirium has led the latest international guideslines to advise against their use, thereby generating a current of opinion that favors banishing them definitely.2,3 However, is such rejection fully justified?

From the start of the century, the group from Vanderbilt University (Nashville, TN, USA), led by Dr. E.W. Ely, has been demonstrating the influence of delirium in the evolution of the critically ill patient. This group has shown that delirium is a strong predictor of prolonged mechanical ventilation (MV), longer ICU stay, greater costs, neurocognitive deterioration, and even death.4 Different studies by the aforementioned group that focus on the search for delirium risk factors, have suggested that delirium is associated with benzodiazepine exposure (lorazepam or midazolam), a finding that has been corroborated by other authors. However, it must be noted that additional studies indicate that oversedation with the induction of coma together with the duration of the latter, are the main determinants of delirium, more than the actual sedative drug itself.5 The PRE-DELIRIC scale, used to predict delirium in the critically ill, contemplates coma induced by drugs and not the use of a drug in particular, as one of the determinants for the development of delirium.6 On the other hand, delirium in postsurgical patients is also a frequent complication, and in this context of general anesthesia, midazolam rarely is part of the pharmacological strategy. It seems that excessive anesthetic depth, with the production of electroencephalographic suppression phases is the factor more closely related to delirium, and not the use of any particular anesthetic agent.7

It could be postulated that the mechanism of action of midazolam may be responsible for the appearance of delirium. However, propofol and the inhaled sedatives (isoflurane and sevoflurane), in the same way as the benzodiazepines, act mainly upon the GABA receptor, and there is no evidence to suggest that differences in affinity for one subunit of the receptor or the other would account for the appearance of delirium.

Compared with propofol and the inhaled sedatives, midazolam has a pharmacokinetic profile that is more extensively affected in the critically ill patient, particularly in those with an altered volume of distribution, or in those presenting with renal and/or liver failure. Moreover, its metabolism, mediated by the cytochrome P450 enzyme system, can be modified by different drugs. All this implies that midazolam, when used in continuous infusion and without close monitoring, can accumulate, and once suspended, its residual effect may linger over time, causing delays in awakening and weaning from mechanical ventilation – with all the undesirable consequences that this implies. Midazolam, when compared with the rest of the sedatives, is associated more often and during a more polonged period of time with anterograde amnesia, and this, together with the residual effect of the drug, can cause the assessment of delirium using the most common scale (Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit) in patients with a score on the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale of −3 to −1 to produce positive results more frequently than when other sedatives are used. In fact, there are studies on the presence of delirium 48 h after sedative drug suspension that report no differences between midazolam and propofol – a fact that once again suggests that the residual effect of the drug might be the underlying cause.8

Independently of such considerations, it is necessary to assess whether midazolam is still needed, in view of the alternative sedoanalgesic options that are currently available. The sedoanalgesic strategies recommended in the critically ill patient prioritize analgesia and stress the importance of securing a level of sedation that will permit patient communication while preserving their comfort, if the clinical condition allows it. To achieve such desirable conditions nowadays we have very effective drugs, and there is no room for midazolam in the pharmacological armamentarium. However, midazolam has its place in deep sedation strategies, specially if periods of neuromuscular blockade are needed, or in cases where the clinical condition of the patient due to shock, hemodynamic instability or lactic acidosis advises against the use of propofol or volatile anesthetics . Furthermore, severe hypertriglyceridemia (>800 mg/dl) contraindicates the use of propofol, and there is no contrasted experience available on the use of volatile anesthetics for over 24 h. The continued use of sedatives inevitably leads to tolerance, requiring gradual dose increases that can reach toxic levels. Pharmacological alternatives are therefore essential to control this situation.9

In our opinion, midazolam is still needed in the sequential sedoanalgesia strategies of some ventilated critically ill patients, provided a series of conditions are met (Table 1). In addition to having a lower direct pharmacological cost than other sedatives, it has not been demonstrated to date that the binomium delirium-midazolam is an adverse pharmacological effect of the drug; rather, such problems appear to be more related to the usual oversedation that occurs when the drug is used, and its residual sedative effect. Strict monitoring of the depth of sedation, as well as drug switching when the time comes to other sedatives with no cumulative effects, is essential.

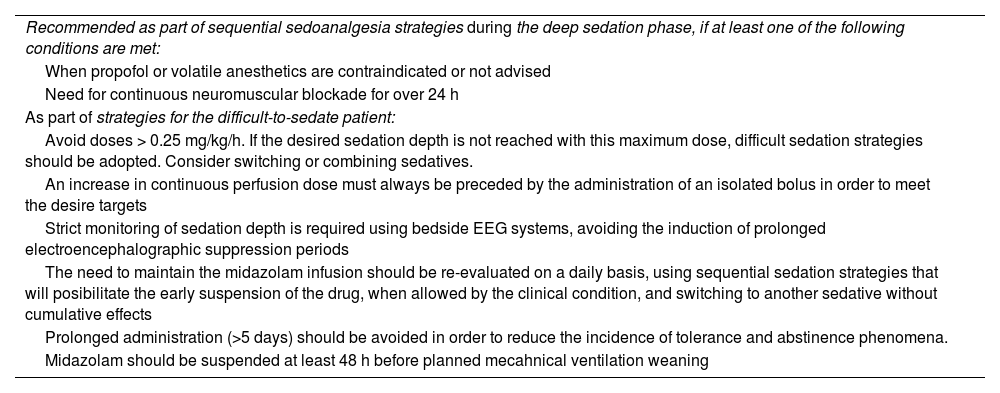

Recommendations for the use of midazolam in continuous sedation in the critically ill patient under mechanical ventilation.

| Recommended as part of sequential sedoanalgesia strategies during the deep sedation phase, if at least one of the following conditions are met: |

| When propofol or volatile anesthetics are contraindicated or not advised |

| Need for continuous neuromuscular blockade for over 24 h |

| As part of strategies for the difficult-to-sedate patient: |

| Avoid doses > 0.25 mg/kg/h. If the desired sedation depth is not reached with this maximum dose, difficult sedation strategies should be adopted. Consider switching or combining sedatives. |

| An increase in continuous perfusion dose must always be preceded by the administration of an isolated bolus in order to meet the desire targets |

| Strict monitoring of sedation depth is required using bedside EEG systems, avoiding the induction of prolonged electroencephalographic suppression periods |

| The need to maintain the midazolam infusion should be re-evaluated on a daily basis, using sequential sedation strategies that will posibilitate the early suspension of the drug, when allowed by the clinical condition, and switching to another sedative without cumulative effects |

| Prolonged administration (>5 days) should be avoided in order to reduce the incidence of tolerance and abstinence phenomena. |

| Midazolam should be suspended at least 48 h before planned mecahnical ventilation weaning |

EEG, electroencephalogram.

The abundant evidence indicates that delirium is a common and serious complication in critically ill patients. Instead of focusing on a sedative in particular as the cause of the appearance and development of delirium, we should search for the pertinent link between the sedative and the clinical situation, applying sequential sedation strategies that will adjust to the evolution of the patient. In this context, we should avoid oversedation, defined as the use of a level of sedation greater than what is actually required by the patient in a given moment, and the induction during deep sedation (if needed) of electroencephalographic suppression phases.10

Although our understanding of delirium has improved, many gaps in knowledge remain, and only studies in search of intrinsic predisposing factors will be able to fill them and clarify the biological mechanisms involved in the development of delirium.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in relation to this publication.

Thanks are due to Dr. M.A. Romera for the revision of the text and the contributions made.