To describe end-of-life care practices relevant to organ donation in patients with devastating brain injury in Spain.

DesignA multicenter prospective study of a retrospective cohort. Period: 1 November 2014 to 30 April 2015.

SettingSixty-eight hospitals authorized for organ procurement.

PatientsPatients dying from devastating brain injury (possible donors). Age: 1 month-85 years.

Primary endpointsType of care, donation after brain death, donation after circulatory death, intubation/ventilation, referral to the donor coordinator.

ResultsA total of 1970 possible donors were identified, of which half received active treatment in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) until brain death (27%), cardiac arrest (5%) or the withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy (19%). Of the rest, 10% were admitted to the ICU to facilitate organ donation, while 39% were not admitted to the ICU.

Of those patients who evolved to a brain death condition (n=695), most transitioned to actual donation (n=446; 64%). Of those who died following the withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy (n=537), 45 (8%) were converted into actual donation after circulatory death donors. The lack of a dedicated donation after circulatory death program was the main reason for non-donation.

Thirty-seven percent of the possible donors were not intubated/ventilated at death, mainly because the professional in charge did not consider donation alter discarding therapeutic intubation.

Thirty-six percent of the possible donors were never referred to the donor coordinator.

ConclusionsAlthough deceased donation is optimized in Spain, there are still opportunities for improvement in the identification of possible donors outside the ICU and in the consideration of donation after circulatory death in patients who die following the withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy.

Describir las prácticas clínicas al final de la vida relevantes para la donación de órganos en pacientes con daño cerebral catastrófico en España.

DiseñoEstudio multicéntrico prospectivo de una cohorte retrospectiva. Periodo: 1 de noviembre de 2014 al 30 de abril de 2015.

ÁmbitoSesenta y ocho hospitales autorizados para donación.

PacientesPacientes fallecidos por daño cerebral catastrófico (posibles donantes). Edad: 1 mes-85 años.

Variables de interés principalesCuidado recibido, donación en muerte encefálica, donación en asistolia controlada, intubación/ventilación, notificación al coordinador de trasplantes.

ResultadosSe identificaron 1.970 posibles donantes. La mitad recibió tratamiento activo en una Unidad de Críticos (UC) hasta evolucionar a muerte encefálica (27%), sufrir una parada cardiorrespiratoria (5%), o hasta la limitación de tratamiento de soporte vital (19%). Del resto, un 10% ingresó en una UC para facilitar la donación y el 39% nunca ingresó en una UC.

De los pacientes que evolucionaron a muerte encefálica (n=695), la mayoría derivaron en una donación eficaz (n=446; 64%). De los pacientes fallecidos tras limitación de tratamiento de soporte vital (n=537), 45 (8%) se convirtieron en donantes en asistolia eficaces. La ausencia de un programa de donación en asistolia controlada fue el motivo más frecuente de no donación.

El 37% de los posibles donantes falleció sin intubar/ventilar, fundamentalmente porque el profesional responsable no consideró la donación tras descartar intubación terapéutica.

El 36% de los posibles donantes no fue notificado al coordinador de trasplantes.

ConclusionesAunque el proceso de donación está optimizado en España, existen oportunidades para la mejora en la detección de posibles donantes fuera de UC y en la consideración de la donación en asistolia controlada en pacientes fallecidos tras limitación de tratamiento de soporte vital.

Organ donation has reached extraordinary levels in Spain, with sustained rates of 32–36 donors per million inhabitants in recent years.1 These results are the consequence of a highly effective system capable of identifying donation opportunities and of transforming possible donors into effective donors. The system is centered on the transplant coordinator (TC) and on close cooperation between the TC and the professionals in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU).2

However, the need to continue progressing with the aim of achieving self-sufficiency in transplantation3,4 is confronted by a gradual decrease in the incidence of brain death (BD) in this country.5 On the other hand, we are witnessing substantial changes in end-of-life care, including the consideration of limitation or withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment (WLST) once a situation of therapeutic futility has been reached.6

The development of new strategies capable of increasing organ availability requires very precise knowledge of the donation process. Such knowledge must also refer to the initial phases, including clinical decision making by the professionals attending patients with devastating brain injury in the end-of-life stage, since such decisions serve to either maintain or discard the donation options. This information is essential in order to identify possibilities for improvement from a dual perspective: that of the transplant coordination system, which must adapt its activity to the new circumstances; and that of the critical care professionals, who must integrate donation options with end-of-life care in variable clinical scenarios.3

ACCORD-España,7 an extension of the ACCORD joint initiative,8 is a project led by the Spanish National Organization of Transplants (NOT) with the support of the Transplants Commission of the Inter-territorial Health Council. The project aims to determine the relevant end-of-life clinical practices referred to organ donation in patients with devastating brain injury in Spain, and to offer hospitals tools for change. The present article focuses on the description of these practices and on the opportunities for improvement in the donation process identified at national level.

Patients and methodsA prospective multicenter study of a retrospective cohort was carried out.

The hospitals authorized for organ harvesting in Spain through their corresponding Autonomous and Hospital Coordination of Transplant Systems were invited to participate in the study. The hospitals that were interested reported their participation to the National Organization of Transplants and assigned a professional belonging to Hospital Coordination of Transplants as the person in charge of the study. Specific approval was obtained from the management board of each center, with a positive opinion from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee or Reference Committee.

Terminology- •

Possible donor: a patient who has died as a consequence of devastating brain injury.

- •

Potential brain dead donor: a patient who has died in a clinical situation consistent with BD, in the absence of medical contraindications to organ donation.

- •

Potential non-heart beating donor: a patient who has died following WLST, in the absence of medical contraindications to organ donation and aged under 70 years – this usually being taken as the age limit for controlled non-heart beating donation (CNHBD).9

- •

Effective donor: a patient who has died and has been subjected to surgical incision with the purpose of harvesting organs for transplantation.

- •

Non-therapeutic elective ventilation (VENT): the start of mechanical ventilation with the purpose of facilitating organ donation.

We included all possible donors aged between one month and 85 years (both included) that died in any Unit of the hospital during the period between 1 November 2014 and 30 April 2015.

The identification of possible donors was based on a review at least twice a week of the diagnoses of those patients that died in the hospital. The list of diagnoses according to the International Classification of Diseases—Tenth Edition (ICD-10) most frequently related to serious brain damage allowed the retrospective assessment of thoroughness in the exclusion of cases.7,10 After identification of the possible donors on the basis of these diagnoses, the professional in charge of the study in each center reviewed the patient case history to discard alternative causes of death that would lead to exclusion of the case and to collect the necessary information for the study. Where required, the information available in the case history was contrasted with the team in charge of patient management.

Variables and data collectionAn ad hoc questionnaire was designed to compile information referred to the clinical and demographic characteristics of the possible donors and the clinical decisions made during end-of-life care, particularly:

- •

The scenario that best described the care received: A: active treatment in an ICU until the patient evolved to BD, independently of whether this diagnosis was subsequently confirmed or not; B: active treatment in an ICU until the patient suffered unexpected cardiac arrest (CA) without recovery; C: admission to an ICU with the purpose of incorporation the option of donation to end-of-life care; D: active treatment in an ICU until WLST was decided, with ulterior CA; E: no admission to an ICU.

- •

Whether the patient was intubated and subjected to mechanical ventilation at the time of death or when WLST was decided.

- •

Whether the situation evolved toward a clinical condition consistent with BD.

- •

Whether a diagnosis of BD was made and confirmed.

- •

Whether CNHBD was considered in the event WLST was decided.

- •

Whether the possible donor was reported to the TC.

- •

Whether the possibility of donation was commented with the family.

- •

Whether surgical incision was made with the purpose of harvesting organs for transplantation (effective donation).

Information was collected on the main reason for each decision discarding the option of donation and on the professionals that participated in the decisions in each phase of the process.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis (absolute numbers and percentages) was made. A study was made of the relationship between different factors and the intubation/ventilation of possible donors, the reporting of such possible donors to the TC, and the obtainment of consent for donation. The chi-squared test (with Fisher test correction where required) was used. A binary logistic regression model was developed to analyze the independent relationship between each of the variables and the outcomes referred to intubation/ventilation, reporting to the TC, and consent, respectively. Those variables found to exhibit a statistically significant relationship (p<0.05) in the univariate analysis were entered in each of the constructed models. The SPSS version 15.0 statistical package was used throughout.

ResultsA total of 68 of the 189 hospitals authorized for organ harvesting (36%) participated in the study. These centers contributed 66% of the effective donors in Spain during the year 2013. Of the participating hospitals (all public centers), 38 (56%) had a Department of Neurosurgery, and 25 (37%) performed some type of organ transplantation. This hospital distribution is similar to that recorded for the global hospitals authorized for organ harvesting in Spain.

Demographic and clinical data of the possible donorsDuring the study period, we identified 1970 possible donors that met the specified inclusion criteria. Their characteristics are shown in Table 1. In relation to the cause of death, intracranial hemorrhage (I61), stroke (I63), postanoxic encephalopathy (G931) and diffuse brain injury (S062) accounted for the death of 70% of the possible donors.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the possible donors.

| n=1970 | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| <18 years | 28 | 1.4 |

| 18–59 years | 472 | 23.9 |

| 60–69 years | 371 | 18.8 |

| 70–79 years | 618 | 31.4 |

| ≥80 years | 481 | 24.4 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1112 | 56.4 |

| Main cause of death (ICD-10) | ||

| Stroke | 1257 | 63.8 |

| Trauma | 290 | 14.7 |

| Other brain damage | 299 | 15.2 |

| Central nervous system infection | 42 | 2.1 |

| Brain tumor | 78 | 4.0 |

| Other | 4 | 0.2 |

| Time of devastating brain injury | ||

| Before hospital admission | 1634 | 83.0 |

| During hospital stay | 336 | 17.0 |

| Time from devastating brain injury to death | ||

| 0 days | 326 | 16.5 |

| 1 day | 460 | 23.4 |

| 2 days | 268 | 13.6 |

| 3 days | 181 | 9.2 |

| 4 to 9 days | 496 | 25.1 |

| ≥10 days | 241 | 12.2 |

| Absolute or relative medical contraindications to donation | 640 | 32.5 |

Although devastating brain injury was the reason for admission to hospital in most cases, 17% of the patients developed devastating brain injury during admission to hospital. The time elapsed from brain damage to death was ≤3 days in 63% of the patients. In one-third of the cases, it was considered that there were absolute or relative medical contraindications to donation—the most frequent being current or past antecedents of malignant disease (49%), vascular disease and multi-disease processes (21%) and sepsis or active infectious diseases (11%).

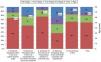

Fig. 1 shows the Units in which the possible donors died. A total of 41% were seen to have died outside an ICU—fundamentally in a hospital ward.

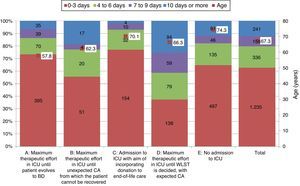

Scenario best describing end-of-life careThe distribution of possible donors according to the scenario is detailed below:

- •

A (active treatment in ICU until BD): 539 (27%)

- •

B (active treatment in ICU until unexpected CA): 92 (5%)

- •

C (admission to ICU for donation): 200 (10%)

- •

D (active treatment in ICU until WLST decision): 370 (19%)

- •

E (no admission to ICU): 769 (39%)

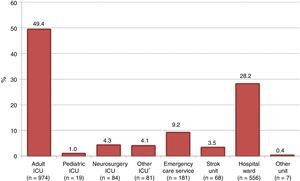

The characteristics of the possible donors varied according to the scenario involved. Fig. 2 shows these variations for age and time from brain damage to death.

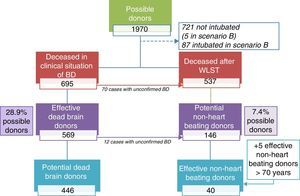

Dead brain donation processFig. 3 shows the distribution of the patients that evolved to BD. Of the 695 patients that reached this clinical situation, 569 (29% of the possible donors and 82% of the patients in BD) had no medical contraindications to organ donation, and thus represented the potential sample for dead brain donation.

Graphic representation of the transition from possible donors to potential and effective donors, under conditions of brain death and controlled asystole. Possible donor: death secondary to devastating brain injury. Potential brain dead donor: death in clinical situation consistent with BD and without absolute or relative medical contraindications to organ donation. Potential non-heart beating donor: death following WLST, without absolute or relative medical contraindications to organ donation, and aged under 70 years. Effective donor: death with surgical incision made for organ harvesting for transplantation. Scenario B: includes possible donors actively treated in an Intensive Care Unit until unexpected cardiac arrest occurs from which the patient cannot be recovered. WLST: withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment; BD: brain death.

The reasons why dead brain patients did not progress to effective donation were medical contraindication (41%) followed by family refusal (36%), the impossibility of confirming the diagnosis of BD (9%), CA or hemodynamic instability (6%) and other reasons (8%).

A total of 446 possible donors resulted in effective donation under conditions of BD (23% of the total possible donors and 64% of the cases in BD).

Controlled non-heart beating donation processAs can be seen in Fig. 3, 537 patients died after WLST, which included terminal extubation in 58% of the cases. Of these possible donors, only 146 had no medical contraindications and were under 70 years of age—representing the potential sample for CNHBD (7% of the possible donors and 27% of those who died after WLST).

The possibility of CNHBD was not considered in 79% of the patients who died after WLST—the main reason being the lack of a program of this kind in the corresponding hospital.

Of the 115 cases in which CNHBD was indeed considered after WLST, the main reasons for non-progression to effective donation were medical contraindication (60%), family refusal (13%) and other reasons (27%). None of these cases involved death occurring beyond the time considered compatible with CNHBD once the procedure had been activated.

Lastly, 45 possible donors resulted in effective CNHBD (2% of the possible donors and 8% of those who died after WLST).

Intubation and ventilationOf the 1970 possible donors, 721 (37%) were not intubated/ventilated at the time of death or when the decision of WLST was made. In over one-half of the cases, the reason for non-intubation/ventilation was that the professional in charge of the patient did not consider the possibility of non-therapeutic elective ventilation (VENT) after making the decision to not intubate/ventilate with curative intent. In contrast, of those patients who were indeed intubated/ventilated at the time of death, the purpose of intubation/ventilation was considered to be the facilitation of organ donation (VENT) in 14% of the cases.

Several factors corresponding to the hospital and possible donor were identified referred to the intubation/ventilation of possible donors (Table 2). Of the potentially modifiable factors, the availability of WLST protocols in the hospital was independently correlated to a greater probability of mechanical ventilation (OR 1.78 [1.31–2.43]; p<0.001). On the other hand, the probability of intubation/ventilation was greater when the decision depended on the intensivists or out-hospital care professionals, compared with professionals of other areas or specialties.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of the factors related to intubation/ventilation of possible donors.

| n | % intubated/ventilated possible donors | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | OR [CI] | p | |||

| Number of beds in adult ICU | |||||

| <30 | 803 | 55.4% | <0.001 | Ref. | 0.562 |

| ≥30 | 1167 | 68.9% | 1.12 [0.76–1.66] | ||

| Neurosurgery | |||||

| Yes | 1470 | 68.9% | <0.001 | 1.47 [1.01–23] | 0.043 |

| No | 500 | 47.2% | Ref. | ||

| Transplant | |||||

| Yes | 1249 | 72.3% | <0.001 | 2.00 [1.41–2.82] | <0.001 |

| No | 988 | 54.6% | Ref. | ||

| WLST protocols | |||||

| Yes | 1318 | 67.1% | <0.001 | 1.78 [1.31–2.43] | <0.001 |

| No/not known | 652 | 55.8% | Ref. | ||

| Age of possible donor | |||||

| <60 years | 500 | 85.4% | <0.001 | 3.37 [2.21–5.15] | <0.001 |

| ≥60 years | 1470 | 55.9% | Ref. | ||

| Cause of death of possible donor | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Stroke | 1.257 | 56.2% | Ref. | 0.035 | |

| Trauma | 290 | 72.4% | 1.58 [1.03–2.41] | <0.001 | |

| Other brain damage | 303 | 87.8% | 5.07 [2.97–8.64] | <0.001 | |

| CNS infection | 42 | 81% | 9.59 [3.30–27.99] | 0.795 | |

| Brain tumor | 78 | 42.3% | 1.11 [0.49–2.51] | ||

| Contraindications to donation | |||||

| Yes | 640 | 51.4% | <0.001 | 0.35 [0.26–0.47] | <0.001 |

| No | 1330 | 69.2% | Ref. | ||

| Patient referred to neurosurgery | |||||

| Yes | 925 | 70.9% | <0.001 | 1.76 [1.28–2.41] | <0.001 |

| No/not known | 1045 | 56.7% | Ref. | ||

| Specialty/working area of the main professional in intubation/ventilation decision | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Critical care medicinea | 878 | 82% | Ref. | <0.001 | |

| Out-hospital medicine | 263 | 98.9% | 17.91 [5.58–57.57] | <0.001 | |

| Emergency care medicine | 319 | 55.8% | 0.29 [0.21–0.40] | <0.001 | |

| Neurology/Neurosurgery | 275 | 5.5% | 0.01 [0.05–0.02] | <0.001 | |

| Other specialty | 132 | 11.4% | 0.03 [0.02–0.07] | ||

WLST: withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment; Ref.: reference; CNS: central nervous system; ICU: Intensive Care Unit.

Thirty-six percent of the possible donors were not reported to the TC at any time during their evolutive course. In over one-half of the cases the reason for not notifying the TC was failure by the supervising physician to identify the patient as a possible organ donor, followed in order of frequency by the existence of medical contraindications to donation.

The study of the factors related to notification of possible donors to the TC (Table 3) showed the existence of written notification criteria in the hospital to significantly increase the probability of notification (OR 1.46 [1.07–1.99]; p=0.017). The probability of notifying the TC also increased significantly when the notification of a possible donor depended upon Intensive Care Medicine, Anesthesia or Cardiology versus other specialties or disciplines.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors related to the notification of possible donors to the transplant coordinator.

| n | % possible donors notified to the TC | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | OR [CI] | p | |||

| Neurosurgery | |||||

| Yes | 1.470 | 66.8% | <0.001 | 0.70 [0.48–0.1.01] | 0.056 |

| No | 500 | 52.6% | Ref. | ||

| Transplantation | |||||

| Yes | 982 | 70.8% | <0.001 | 1.86 [1.35–2.56] | <0.001 |

| No | 988 | 55.7% | Ref. | ||

| WLST protocols | |||||

| Yes | 1.318 | 67.4% | <0.001 | 1.30 [0.96–1.75] | 0.091 |

| No/not known | 652 | 54.8% | Ref. | ||

| Written criteria for notification to TC | |||||

| Yes | 1.408 | 65.6% | <0.001 | 1.46 [1.07–1.99] | 0.017 |

| No/not known | 562 | 57.1% | Ref. | ||

| Age of the possible donor | |||||

| <60 years | 500 | 82.2% | <0.001 | 2.36 [1.63–3.43 | |

| ≥60 years | 1.470 | 56.7% | Ref. | <0.001 | |

| Cause of death of the possible donor | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Stroke | 1.257 | 61.3% | Ref. | ||

| Trauma | 290 | 64.8% | 0.49 [0.33–0.73] | <0.001 | |

| Other brain damage | 303 | 75.6% | 0.82 [0.53–1.27] | 0.374 | |

| CNS infection | 42 | 69% | 0.89 [0.37–2.16] | 0.126 | |

| Brain tumor | 78 | 35.9% | 0.22 [0.11–0.52] | <0.001 | |

| Contraindications to donation | |||||

| Yes | 640 | 53.8% | <0.001 | 0.58 [0.45–0.79] | <0.001 |

| No | 1.330 | 67.7% | Ref. | ||

| Patient referred to Neurosurgery | |||||

| Yes | 1.249 | 85.8% | <0.001 | 1.86 [1.37–2.52] | <0.001 |

| No/not known | 721 | 24.0% | Ref. | ||

| Specialty/working area of the main professional deciding notification to TC | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Critical care medicinea | 1.091 | 86.7% | Ref. | ||

| Emergency care medicine | 201 | 46.3% | 0.15 [0.10–0.21] | <0.001 | |

| Neurology/neurosurgery | 275 | 22.5% | 0.04 [0.03–0.06] | <0.001 | |

| Other specialty | 127 | 9.4% | 0.02 [0.01–0.05] | <0.001 | |

TC: transplant coordinator; WLST: withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment; Ref.: reference; CNS: central nervous system.

No interviewing of the family to explain about organ donation was carried out in 61% of the total possible donors. The main reason for not interviewing the family was the existence of medical contraindications to donation, though in 21% of the cases the reason was failure by the supervising physician to identify the patient as a possible organ donor.

Consent to organ donation was obtained in 76% of the 765 family interviews carried out. Participation of the TC in the family interview significantly increased the probability of obtaining consent (OR 1.86 [1.37–2.52]; p<0.001) (Table 4). The probability was also seen to be greater when the interview took place after notifying the patient to the TC. Although statistical significance was not reached in the multivariate model, differences were observed in the obtainment of consent according to the timing of the family interview. In this sense, consent was greater when the interview took place with the patient in BD, or when BD was expected to occur within the ICU, compared with the rest of the clinical situations.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors related to the obtainment of consent to donation.

| n | % family interviews with consent | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | OR [CI] | p | |||

| Number of adult ICU beds | |||||

| <30 | 262 | 180 (68.7%) | <0.001 | 1.78 [1.23–2.57] | 0.002 |

| ≥30 | 491 | 394 (80.2%) | Ref. | ||

| Neurosurgery | |||||

| Yes | 593 | 465 (78.4%) | 0.007 | 0.86 [0.50–1.49] | 0.595 |

| No | 160 | 109 (68.1%) | Ref. | ||

| Transplantation | |||||

| Yes | 444 | 356 (80.2%) | 0.002 | 1.17 [0.73–1.89] | 0.511 |

| No | 309 | 218 (70.6%) | Ref. | ||

| Cause of death of the possible donor | 0.015 | – | 0.286 | ||

| Stroke | 497 | 361 (72.6%) | |||

| Trauma | 115 | 96 (83.5%) | |||

| Other brain damage | 118 | 96 (81.4%) | |||

| CNS infection | 11 | 11 (100%) | |||

| Brain tumor | 12 | 10 (83.3%) | |||

| Protocolized training of professionals participating in the interviewa | |||||

| Yes | 719 | 554 (77.1%) | <0.001 | – | – |

| No/not known | 13 | 3 (23.1%) | |||

| Time of interview | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| After notifying TC | 611 | 475 (77.7%) | Ref. | 0.001 | |

| Before notifying TC | 94 | 54 (57.4%) | 0.42 [0.24–0.70] | 0.024 | |

| The family asked | 42 | 41 (97.6%) | 10.18 [1.36–76.41] | ||

| Time of interview | 0.001 | 0.062 | |||

| On deciding WLST | 93 | 58 (62.4%) | Ref. | ||

| Before intubation/ventilation | 79 | 55 (69.6%) | 1.74 [0.88–3.45] | 0.116 | |

| Intubated before BD-outside ICU | 56 | 39 (69.6%) | 1.43 [0.66–3.13] | 0.366 | |

| Intubated but before BD-within ICU | 93 | 75 (80.6%) | 2.23[1.08–4.58] | 0.029 | |

| BD but prior to confirmation | 108 | 92 (85.2%) | 2.95 [1.45–5.98] | 0.003 | |

| After confirmation of BD | 317 | 250 (78.9%) | 1.77 [1.04–3.03] | 0.037 | |

| Participation of the TC in the interview | |||||

| Yes | 511 | 180 (68.7%) | <0.001 | 1.86 [1.37–2.52] | <0.001 |

| No | 219 | 394 (80.2%) | Ref. | ||

TC: transplant coordinator; WLST: withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment; Ref.: reference; CNS: central nervous system.

Includes refusal expressed by family or by patient while alive.

Two hundred patients were admitted to intensive care for intended organ donation (scenario C). Of these patients, 150 (75%) evolved toward BD and 113 became effective dead brain donors. The main reasons why the remaining 37 patients did not progress to effective donation were medical contraindication (46%) followed by family refusal (35%), non-confirmation of the diagnosis of BD (5%), and other reasons (14%).

Of the 55 patients admitted to intensive care for intended organ donation and which did not evolve toward BD or in which the diagnosis of BD was not confirmed, 11 (20) were considered for CNHBD, and 7 (64%) became effective non-heart beating donors.

Admission to the ICU for donation (either BD or CNHBD) contributed 24% of the effective donations during the study period (120 of the 491 effective donations).

The possibilities for improving donation via admission to intensive care were illustrated by the analysis of the possible donors not admitted to the ICU (scenario E). In over one-half of the 769patients, the possibility of admission to intensive care for incorporating organ donation to end-of-life care was not considered. Specifically, 342 patients without medical contraindications for donation were never reported to the TC. Most of these patients were not intubated/ventilated at the time of death.

DiscussionTo our knowledge, this is the first study to offer a detailed evaluation of the decision-making process in end-of-life care from the organ donation perspective in Spain.

In concordance with the profile of the effective brain dead donors in this country, a high percentage of possible donors are very elderly (≥80 years). This reflects the increasingly imperative need to use organs from elderly donors—a practice that has already been implanted in Spain, with adequate post-transplantation outcomes.11–14

The study shows that the donation process in cases of BD is optimized in this country from the moment in which the patient suffers BD, and thus in the different phases of the process that take place in an ICU. These Units are the great strength of our system.2,15

Despite the above, the study has identified opportunities for improvement that are evidenced in the description of the end-of-life care scenarios: 40% of the possible donors never enter the ICU (scenario E)—often without admission for possible organ donation having been considered. On the other hand, almost 20% of the possible donors die following WLST (scenario D). Only recently has donation under these circumstances of death become possible in our country.

The possibilities for donation among patients who currently die outside an ICU require some consideration referred to the notification of possible donors to the TC, admission to intensive care for donation and VENT, derived from this study.

Routine and early notification (before death occurs) of possible donors to the TC is considered good practice at international level.16–18 However, 36% of the possible donors in Spain are not notified to the TC at any time during their evolution—mainly because the professionals in charge do not identify the patient as a possible donor, or because they consider that there are contraindications—without having discussed them with the TC. In Spain, it is recommended that the professionals attending neurocritical patients should systematically consider the option of donation when brain damage is devastating and any ulterior treatment is regarded as futile.19 This consideration requires a training effort targeted particularly to the professionals of Units outside the intensive care setting, since these are professionals who, according to the results of our study, generated fewer notifications to the TC. On the other hand, we also observed that the existence of written notification criteria increased the probability of notification by 46%. In establishing these criteria, it is essential to emphasize the need to discuss apparent contraindications with the TC, since the absolute contraindications to organ donation are currently very limited. In fact, external audits of Spanish hospitals have found that the existence of contraindications was established inadequately in over 10% of the potential donors not notified due to medical reasons.5

If the notification of possible donors were to be systematically implemented from Units outside the intensive care setting, it would be necessary to consider a policy of admission to the ICU for donation and VENT. Our study shows that this strategy could very significantly increase the opportunities for donation. Non-therapeutic elective ventilation (VENT) is warranted by our ethical-legal and deontological guidelines.20 At international level, it is also increasingly accepted that health professionals must work in the best interest of the patient—such interest being understood not only from the clinical perspective but also as a holistic concept including the beliefs and moral values of the person.21–23 If the patient wished to serve as a donor, raising the option of donation and facilitating it should be viewed as an ethical imperative and a standard of professional practice. In this context, and without breaching the principle of nonmaleficence, the current international literature is mostly favorable to VENT,24–29 and several countries now describe this practice.8

Our experience shows that admission to intensive care for donation and VENT has become a reality in Spain30,31 and makes a key contribution to donation activity—making it possible to underscore the challenges that face this practice:

- •

Although the time to death is under three days in most of the possible donors admitted to the ICU for donation (scenarioC), one out of every four patients does not evolve toward BD. It is therefore crucial to ensure strict selection of those cases with a high probability of evolution to BD and to introduce WLST protocols—this being a factor independently correlated to the intubation/ventilation of possible donors. In some cases, and following patient admission to the ICU, contraindications to donation are established that were not previously detected. It is important to inform the family about this possibility.

- •

Communication with the family to consider admission to the ICU for donation and VENT is complex, with a lesser probability of obtaining consent than when the interview is made with the patient already admitted to intensive care. The participation of the TC in these interviews is therefore particularly important, and has been identified as an independent predictor of increased probability of consent.

- •

Lastly, and despite the policy of maximum transparency, it is not always possible to conduct an interview prior to admission because of the emotional situation of the family, the absence of relatives with decision making capacity or the clinical severity of the patient at risk of immediate respiratory arrest.

In consideration of all the above, admission to the ICU for donation and VENT requires institutional support, training of the professionals attending neurocritical patients and of the TCs, as well as protocols for intervention and for informing the families.

Lastly, our study corroborates the existence of sup-optimized CNHBD in Spain32: in effect, CNHBD is not considered in 79% of the patients that die following WLST (most with terminal extubation), mainly due to the lack of the required program in the hospital involved. Although CNHBD has increased exponentially in recent years,33 the introduction of new programs seems to be necessary. It is also essential for this type of donation not to have a negative impact upon dead brain donation—an issue that remains a source of concern at international level.34,35 The fact that in our series the time elapsed from brain damage to death was longer in the WLST setting (scenario D) than in other scenarios probably reflects the current practice of waiting some time due to the possibility of evolution toward BD before suspending life support measures that have already become futile. On the other hand, as experience is progressively gained with CNHBD in Spain, it will become necessary to reconsider the maximum age of the potential donors—currently defined in most centers as 65–70years.36

The present study has several limitations. Those in charge of data collection belonged to Hospital Coordination of Transplants, and in many aspects conducted a review of their own activities—a fact that may have exerted some influence upon data recruitment. On the other hand, we did not collect information on non-deceased patients with devastating brain injury—a fact that limits some aspects of understanding of the donation process. Lastly, although data collection was conducted on a prospective basis, it was inevitably fundamented upon a retrospective cohort, which required interpretation by the study supervisor of the information contained in the case history—though due contrasting and completion was attempted with the team in charge of the patient.

In conclusion, dead brain donation has been optimized in our system once the patients have evolved to BD. Admission to the ICU for donation and VENT is an established practice contributing 24% of all the effective donations. The opportunities for improvement are represented by the introduction of a systematic policy of possible donor notification to the TC, together with an expanded practice of admission to the ICU in order to facilitate organ donation. Lastly, CNHBD is confirmed to be a great opportunity for ensuring that donation forms an integral part of end-of-life care, independently of the circumstances of death of our patients.

Authorship/collaboratorsBDG, EC, TP, ML, EM and RM conceived of and designed the study, and participated in the interpretation of the data. BDG and EC performed the data analysis. All the authors participated in the preparation of the article, its critical review and in definitive approval of the manuscript version submitted for publication. The authors of the hospital centers represented in the study participated in the identification of possible donors and facilitated acquisition of the data required for the study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors thank all the Autonomous and Coordination of Transplant Systems for the support received in developing this project. Thanks are also due to Pablo Delgado, Amparo Luengo and Bibiana Ramos, of the Spanish National Organization of Transplants, for the crucial and continuous administrative, statistical and software support received. Lastly, we wish to thank the international ACCORD consortium and particularly NHS Blood and Transplant, supervising work group 5, for the tools developed and the knowledge gained during the mentioned project.

Alejandra Álvarez-Saiz (H. de Riotinto), Aránzazu Anabitarte (H.U. de Gran Canarias Dr. Negrín), Juan José Aráiz (H. Clínico U. Lozano Blesa), Jose Ignacio Aranzábal (H. de Galdakao y H. U. de Cruces), Juan Bautista Araujo (H. General Virgen de la Luz), Eva María Arias (H. La Línea de la Concepción y H. Punta de Europa), Vicente Arráez (H. General U. de Elche), Manuel Luis Avellanas (H. General de San Jorge), Lourdes Benítez (H.U. Puerta del Mar), José Blanco (C.H. U. Insular Materno-Infantil), María Amparo Bodí (H.U. Joan XXIII de Tarragona), José Bravo (C.H.U. de Pontevedra), Francisco Caballero (H. Santa Creu i Sant Pau), Francisca Cabeza (C.H.U. de Huelva Juan Ramón Jiménez), Francisco Carrizosa (H. Jerez de la Frontera), Ana Casamitjana (C.H.U. Insular Materno-Infantil), Ramón Claramonte (H. de Tortosa Verge de la Cinta), Ruth Corpas (H. General Nuestra Señora del Prado), Esther Corral (H. de Santiago), Juan Ramón Cortés (C.H.U. de Ourense), Domingo Daga (H. U. Virgen de la Victoria), José María Díaz (C.H. de Toledo), José Elizalde (C.H. de Navarra), Lucía Elosegui (H.U. de Donostia), Dolores Escudero (H. U. Central de Asturias), Ramón Fernández-Cid (H. Mateu Orfila), Juan Galán (H.U. i Politécnic La Fe), José Galván (H. Costa del Sol), Carmen García-Díez (C.H.U. de Huelva Juan Ramón Jiménez), Antonio García-Horcajadas (H. de Baza), Fernando García-López (C.H.U. de Albacete), Francisco Javier Gil-Sánchez (H. General U. Santa Lucía), Elena González- González (H.U. de Torrejón), Elena González- Higueras (H. General Virgen de la Luz), Francisco Guerrero (C.H. de Torrecárdenas), Sonia Ibáñez (H. U. Virgen de Macarena), José Luis Iribarren (C.H.U. de Canarias), María Teresa Jurado (Consorci Sanitari de Terrassa), Pascual Laguardia (H. Royo Villanova), Jesús Larraga (H. Clínico U. Lozano Blesa), José María Manciño (H.U. Germans Trias i Pujol), Fernando Maroto (H. San Juan de Dios del Aljarafe), María Ángeles Márquez (H. San Pedro de Alcántara), Carmen Martín-Delgado (H. General La Mancha Centro), María Cruz Martín- Delgado (H.U. de Torrejón), Pilar Martínez-García (H. Puerto Real), Adolfo Martínez-Pérez (H. U. Ramón y Cajal), Fernando Martínez-Soba (H. de San Pedro), Amelia Martínez-Tárrega (H. Can Misses), José Manuel Mayoral (H. General Nuestra Señora del Prado), Elisa Monfort (H. de San Pedro), Antonia Morante (Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén), Emilio Muñoz-Collado (H. de la Merced), Ascensión Navarro (H. Can Misses), Elisabeth Navas (H.U. Mutua de Terrassa), Agustín Nebra (H. U. Miguel Servet), Juan Pedro Olivas (C.H.U. de Albacete), Francisco Jesús Ortega (H. Virgen de Valme), Jose Ignacio Ortiz-Mera (H. Infanta Elena), Javier Paul (H. U. Miguel Servet), Virginia Peralta (C.H. de Toledo), Maria Rosario Pérez-Beltrán (H. de Basurto), Jose Miguel Pérez-Villares (H. U. Virgen de las Nieves), Luis Alberto Ramos (H. General de la Palma), Juan Carlos Robles (H. U. Reina Sofía), Álvaro Ruigómez (H. U. Ramón y Cajal), Sergio Tomás Rodríguez-Ramos (H.U. Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria), Camino Rodríguez-Villar (H. Clínic de Barcelona), Felicidad Romero (H. General La Mancha Centro), José Luis Romero (H.U. de Gran Canarias Dr. Negrín), Salvadora Saez (H. General U. Santa Lucía), José María Sánchez-Andrade (H. Lucus Augusti), Carlos Santiago (H. General U. de Alicante), Carmen Torrecilla (H.U. de La Princesa), María Concepción Valdovinos (H. Obispo Polanco), Jorge Vallejo (H. Regional U. de Málaga), Alejandro Vázquez (H. de Antequera), Julio Domingo Zambudio (H. Clínico U. Virgen de la Arrixaca).

Please cite this article as: Domínguez-Gil B, Coll E, Pont T, Lebrón M, Miñambres E, Coronil A, et al. Prácticas clínicas al final de la vida en pacientes con daño cerebral catastrófico en España: implicaciones para la donación de órganos. Med Intensiva. 2017;41:162–173.