Edited by: Alberto García-Salido - Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús, Madrid, Spain

Last update: May 2024

More infoTo identify factors associated with prolonged mechanical ventilation (pMV) in pediatric patients in pediatric intensive care units (PICUs).

DesignSecondary analysis of a prospective cohort.

SettingPICUs in centers that are part of the LARed Network between April 2017 and January 2022.

ParticipantsPediatric patients on mechanical ventilation (IMV) due to respiratory causes. We defined IMV time greater than the 75th percentile of the global cohort.

InterventionsNone.

Main variables of interestDemographic data, diagnoses, severity scores, therapies, complications, length of stay, morbidity, and mortality.

Results1698 children with MV of 8±7 days were included, and pIMV was defined as 9 days. Factors related to admission were age under 6 months (OR 1.61, 95% CI 1.17–2.22), bronchopulmonary dysplasia (OR 3.71, 95% CI 1.87−7.36), and fungal infections (OR 6.66, 95% CI 1.87−23.74), while patients with asthma had a lower risk of pIMV (OR 0.30, 95% CI 0.12−0.78). Regarding evolution and length of stay in the PICU, it was related to ventilation-associated pneumonia (OR 4.27, 95% CI 1.79−10.20), need for tracheostomy (OR 2.91, 95% CI 1.89−4.48), transfusions (OR 2.94, 95% CI 2.18−3.96), neuromuscular blockade (OR 2.08, 95% CI 1.48−2.93), high-frequency ventilation (OR 2.91, 95% CI 1.89−4.48), and longer PICU stay (OR 1.13, 95% CI 1.10−1.16). In addition, mean airway pressure greater than 13cmH2O was associated with pIMV (OR 1.57, 95% CI 1.12−2.21).

ConclusionsFactors related to IMV duration greater than 9 days in pediatric patients in PICUs were identified in terms of admission, evolution, and length of stay.

Identificar los factores asociados con la ventilación mecánica prolongada (pVMI) en pacientes pediátricos en la unidad de cuidados intensivos pediátricos (UCIPs).

DiseñoAnálisis secundario de una cohorte prospectiva.

ÁmbitoUCIPs en los centros que integran LARed Network entre abril 2017 y enero 2022.

ParticipantesPacientes pediátricos en ventilación mecánica (VMI) debido a causas respiratorias. Definimos pVMI como eventos con tiempo VMI mayor al percentil 75 global.

IntervencionesNinguna.

Variables de interés principalesDatos demográficos, diagnósticos, puntajes de gravedad, terapias, complicaciones, estancias, morbilidad y mortalidad.

ResultadosSe incluyó 1.698 niños con VMI de 8±7 días, y se definió pVMI en 9 días. Los factores relacionados al ingreso fueron la edad menor de 6 meses (OR1,61, IC 95%1,17−2,22), la displasia broncopulmonar (OR 3,71, IC 95%1,87−7,36) y las infecciones fúngicas (OR 6,66, IC 95%1,87−23,74); mientras que los pacientes con asma tuvieron menor riesgo de pVMI (OR 0,30, IC 95%0,12−0,78). En cuanto a la evolución y la estancia en UCIP, se relacionó a neumonía asociada a la ventilación mecánica (OR 4,27, IC 95%1,79−10,20), necesidad de traqueostomía (OR 2,91, IC 95%1,89−4,48), transfusiones (OR 2,94, IC95%2,18−3,96), bloqueo neuromuscular (OR 2,08, IC 95%1,48−2,93) y ventilación de alta frecuencia (OR 2,91, IC 95% 1,89−4,48) y una mayor estadía en UCIP (OR1,13, IC 95%1,10−1,16). Además, la presión media aérea mayor a 13cmH2O se asoció a pVMI (OR 1,57, IC 95%1,12−2,21).

ConclusionesSe identificaron factores relacionados con VMI de duración mayor a 9 días en pacientes pediátricos en UCIP en cuanto a ingreso, evolución y estancia.

Acute respiratory failure (ARF) is a common cause for admission to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), and between 35% and 64% of these patients require invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV).1,2 Recent studies have shown that between 25% and 34% of the patients with ARF require prolonged invasive mechanical ventilation (pIMV).3–5 This percentage has increased over the past decade following technological advances used in ventilatory support and overall intensive care.4

However, currently, the definition of pIMV in children is unclear, and there is no consensus among experts. Former studies have used arbitrary cutoff timeframes from 96h to 21 days.6–13 This lack of uniformity complicates the comparison and generalization of results across different studies. Therefore, it is crucial to establish a clear and agreed-upon definition of pIMV in the pediatric population to facilitate research and clinical decision-making.10

In addition, prolonged ventilation has been associated with specific risk factors in the pediatric population like age <12 months, weight <10kg, and PRISM scores >20, among others (6–8). These factors can help identify patients at higher risk of developing pIMV and guide proper management strategies.

pIMV has also been associated with worse clinical outcomes like longer lengths of stay, and more morbidity, and healthcare costs.4,14–17 These complications highlight the importance of identifying and predicting the risk of pIMV in the pediatric population to implement preventive interventions and optimize clinical management.

In this context, the objective of this study is to describe a cohort of pediatric patients ventilated due to ARF from the Latin American Collaborative Network (LARed network) registry18 and, using this data, create a definition of pIMV based on statistical frequency (75th percentile). Afterwards, the goal is to determine whether this definition is associated with risk factors and subsequent events during the evolution and stay at the pediatric intensive care unit, as described in the scientific medical literature available. Additionally, a comparison will be drawn with cutoff timeframes described by other authors to assess the adequacy of our observation.

Patients and methodsRetrospective analysis of a cohort with data collected prospectively from the ARF registry of the LARed Network (including nearly 40 hospitals in Latin America).18 All patients who received IMV during their hospital stay from April 2017 through January 2022 were studied.

SubjectsThe registry includes pediatric patients aged 0 months to 18 years admitted to the PICU with a primary cause of respiratory system-related ARF like bronchiolitis, pneumonia, and asthma as determined by the treating physician. These patients are considered to have respiratory failure when they exhibit symptoms such as hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and increased respiratory effort, thus requiring intervention through oxygen therapy and respiratory support. For this analysis, cases that required IMV during their PICU stay were included. To guarantee data homogeneity, patients with prior invasive home ventilatory support and those who, at the study cutoff date, had not been discharged from the PICU or had incomplete data were excluded.

DefinitionsConsidering that several cutoff timeframes from 96h to 21 days have been reported in the medical literature availabl,6–13 we decided to use a statistical definition based on the population distribution, using the closes day to the 75th percentile as the cutoff timeframe of our study. Although this selection may appear arbitrary, it allowed us to characterize a group of children different from most of the other cases of our population, which could identify a potential target for a strategy for quality improvement.

To identify any potential risk factors, those present when the patients were admitted to the PICU were taken into consideration. On the other hand, factors associated with disease progression and length of stay like complications, therapies received, bailout therapies, length of stay,or mortality occurring after the initiation of IMV, were evaluated (Table 1S in Supplementary material).

Data collectionThe LARed database has a prospective data registry from the PICU stay starting with the patient’s admission until his/her discharge. All these data were collected: demographic variables (age, weight, and gender), comorbidities (defined as diseases occurring in addition to the primary disorder and not the current one), probability of death estimated by the pediatric index of mortality version 3 (PIM3) severity scores, diagnoses at admission, vital signs (heart rate, respiratory rate, and saturation), diagnostic aids (x-rays), therapies received (blood transfusion, corticosteroids, antibiotics, antivirals), complications during the stay (ARDS, sepsis, pneumothorax, extubation failure), and outcomes (mortality, length of stay, and new morbidity; the latter was defined as a difference between admission and discharge >3 in the Functional Status Scale [FSS] score).

Statistical analysisThe 75th percentile of the course of mechanical ventilation was estimated to define the pIMV cutoff timeframe in this cohort stratifying patients into 2 different groups: pIMV and non-prolonged mechanical ventilation (npIMV).

Continuous variables were expressed as mean with standard deviation, and median with interquartile range while categorical variables were expressed as absolute frequencies and percentages. To evaluate the difference between patients on pIMV and npIMV, bivariate analysis was performed by dividing variables into 2 different groups: those present at admission (demographic data and clinical characteristics) and those occurring during the PICU stay (treatment, complications, and outcomes). The continuous variables that followed a normal distribution, assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, were processed using the Student t-test and expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). Variables with a non-normal distribution were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test and expressed as median differences with the interquartile range (IQR) of 25% and 75%. Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test and expressed as absolute frequency and percentages. To determine the factors associated with pIMV, a multivariate mixed logistic regression model was adjusted using countries as random effects including the variables that met the following criteria: variables obtained when patients were admitted to the hospital, significant difference in the bivariate analysis, and clinical relevance without belonging to the same causal chain. Collinearity and interactions were tested for each variable to obtain the final models. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 16 statistical software package.

Ethical considerationsThis secondary analysis was presented and approved by the human ethics committee of the Society of Sociedad de Cirugía de Bogotá Hospital de San José, Bogotá, Colombia. Each center participating in the LARed registry had the approval of their respective ethics committee. For this analysis, a waiver of informed consent was approved since the analyzed data is anonymized.

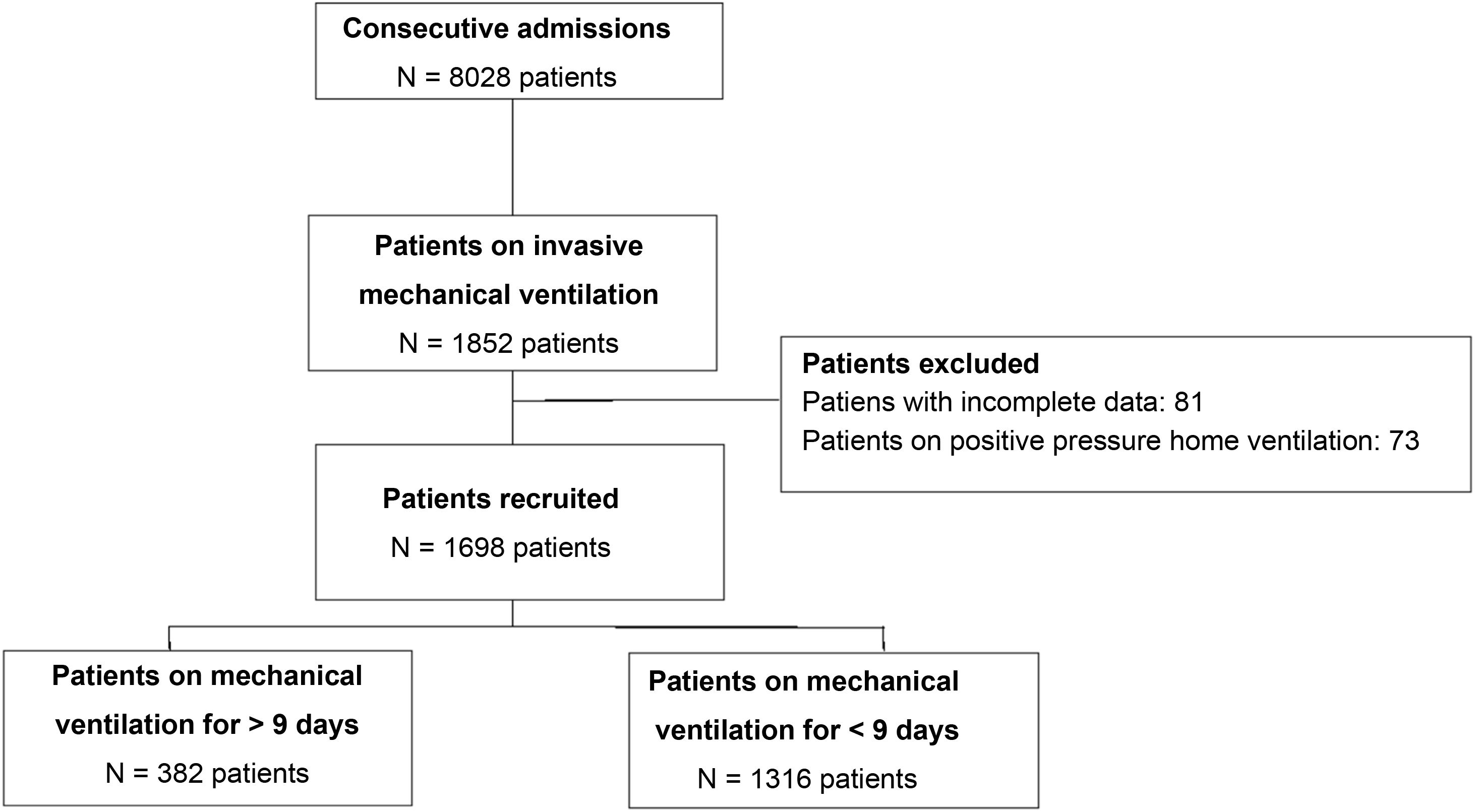

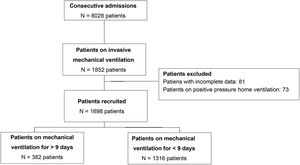

ResultsA total of 8001 patients with ARF were included in the LARed database from April 2017 through January 2022, 1698 of whom were included for analysis (Fig. 1). The mean duration of mechanical ventilation in the entire cohort was 7 +/- 7 days, with a 75th percentile of 9 days. This classified 382 patients (22.5%) on pIMV. Both the distribution and overall survival curve are available in the supplementary data (Figs. 1S, 2S in Supplementary material).

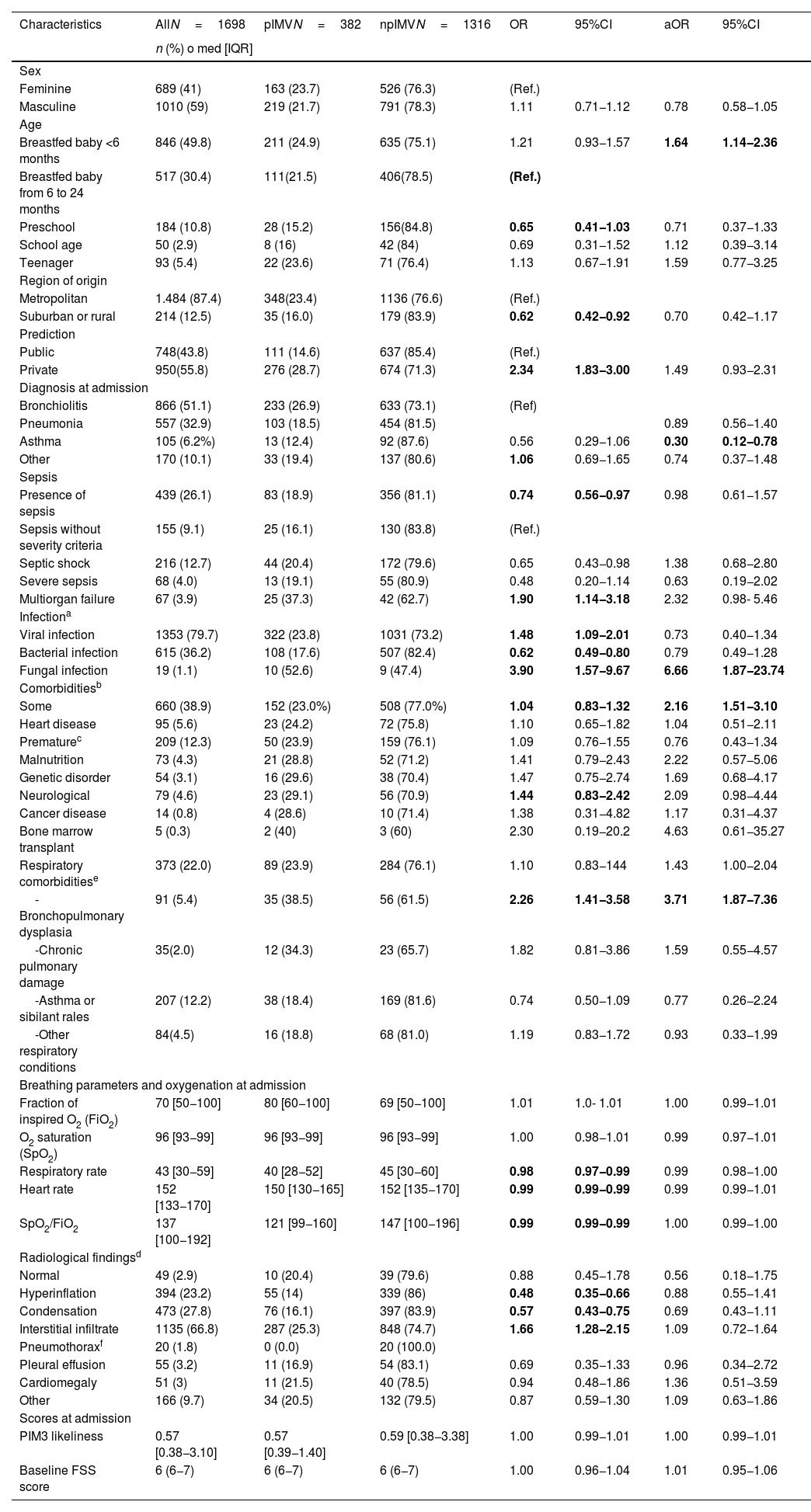

Demographic and admission dataBoth the clinical characteristics and admission data are shown on Table 1. Most of the patients included came from Colombia (602; 35.6%), Uruguay (397; 23.4%), and Chile (201; 11.8%).

Demographic data and admission characteristics of patients included in the study.

| Characteristics | AllN=1698 | pIMVN=382 | npIMVN=1316 | OR | 95%CI | aOR | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) o med [IQR] | |||||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Feminine | 689 (41) | 163 (23.7) | 526 (76.3) | (Ref.) | |||

| Masculine | 1010 (59) | 219 (21.7) | 791 (78.3) | 1.11 | 0.71−1.12 | 0.78 | 0.58−1.05 |

| Age | |||||||

| Breastfed baby <6 months | 846 (49.8) | 211 (24.9) | 635 (75.1) | 1.21 | 0.93−1.57 | 1.64 | 1.14−2.36 |

| Breastfed baby from 6 to 24 months | 517 (30.4) | 111(21.5) | 406(78.5) | (Ref.) | |||

| Preschool | 184 (10.8) | 28 (15.2) | 156(84.8) | 0.65 | 0.41−1.03 | 0.71 | 0.37−1.33 |

| School age | 50 (2.9) | 8 (16) | 42 (84) | 0.69 | 0.31−1.52 | 1.12 | 0.39−3.14 |

| Teenager | 93 (5.4) | 22 (23.6) | 71 (76.4) | 1.13 | 0.67−1.91 | 1.59 | 0.77−3.25 |

| Region of origin | |||||||

| Metropolitan | 1.484 (87.4) | 348(23.4) | 1136 (76.6) | (Ref.) | |||

| Suburban or rural | 214 (12.5) | 35 (16.0) | 179 (83.9) | 0.62 | 0.42−0.92 | 0.70 | 0.42−1.17 |

| Prediction | |||||||

| Public | 748(43.8) | 111 (14.6) | 637 (85.4) | (Ref.) | |||

| Private | 950(55.8) | 276 (28.7) | 674 (71.3) | 2.34 | 1.83−3.00 | 1.49 | 0.93−2.31 |

| Diagnosis at admission | |||||||

| Bronchiolitis | 866 (51.1) | 233 (26.9) | 633 (73.1) | (Ref) | |||

| Pneumonia | 557 (32.9) | 103 (18.5) | 454 (81.5) | 0.89 | 0.56−1.40 | ||

| Asthma | 105 (6.2%) | 13 (12.4) | 92 (87.6) | 0.56 | 0.29−1.06 | 0.30 | 0.12−0.78 |

| Other | 170 (10.1) | 33 (19.4) | 137 (80.6) | 1.06 | 0.69−1.65 | 0.74 | 0.37−1.48 |

| Sepsis | |||||||

| Presence of sepsis | 439 (26.1) | 83 (18.9) | 356 (81.1) | 0.74 | 0.56−0.97 | 0.98 | 0.61−1.57 |

| Sepsis without severity criteria | 155 (9.1) | 25 (16.1) | 130 (83.8) | (Ref.) | |||

| Septic shock | 216 (12.7) | 44 (20.4) | 172 (79.6) | 0.65 | 0.43−0.98 | 1.38 | 0.68−2.80 |

| Severe sepsis | 68 (4.0) | 13 (19.1) | 55 (80.9) | 0.48 | 0.20−1.14 | 0.63 | 0.19−2.02 |

| Multiorgan failure | 67 (3.9) | 25 (37.3) | 42 (62.7) | 1.90 | 1.14−3.18 | 2.32 | 0.98- 5.46 |

| Infectiona | |||||||

| Viral infection | 1353 (79.7) | 322 (23.8) | 1031 (73.2) | 1.48 | 1.09−2.01 | 0.73 | 0.40−1.34 |

| Bacterial infection | 615 (36.2) | 108 (17.6) | 507 (82.4) | 0.62 | 0.49−0.80 | 0.79 | 0.49−1.28 |

| Fungal infection | 19 (1.1) | 10 (52.6) | 9 (47.4) | 3.90 | 1.57−9.67 | 6.66 | 1.87−23.74 |

| Comorbiditiesb | |||||||

| Some | 660 (38.9) | 152 (23.0%) | 508 (77.0%) | 1.04 | 0.83−1.32 | 2.16 | 1.51−3.10 |

| Heart disease | 95 (5.6) | 23 (24.2) | 72 (75.8) | 1.10 | 0.65−1.82 | 1.04 | 0.51−2.11 |

| Prematurec | 209 (12.3) | 50 (23.9) | 159 (76.1) | 1.09 | 0.76−1.55 | 0.76 | 0.43−1.34 |

| Malnutrition | 73 (4.3) | 21 (28.8) | 52 (71.2) | 1.41 | 0.79−2.43 | 2.22 | 0.57−5.06 |

| Genetic disorder | 54 (3.1) | 16 (29.6) | 38 (70.4) | 1.47 | 0.75−2.74 | 1.69 | 0.68−4.17 |

| Neurological | 79 (4.6) | 23 (29.1) | 56 (70.9) | 1.44 | 0.83−2.42 | 2.09 | 0.98−4.44 |

| Cancer disease | 14 (0.8) | 4 (28.6) | 10 (71.4) | 1.38 | 0.31−4.82 | 1.17 | 0.31−4.37 |

| Bone marrow transplant | 5 (0.3) | 2 (40) | 3 (60) | 2.30 | 0.19−20.2 | 4.63 | 0.61−35.27 |

| Respiratory comorbiditiese | 373 (22.0) | 89 (23.9) | 284 (76.1) | 1.10 | 0.83−144 | 1.43 | 1.00−2.04 |

| -Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 91 (5.4) | 35 (38.5) | 56 (61.5) | 2.26 | 1.41−3.58 | 3.71 | 1.87−7.36 |

| -Chronic pulmonary damage | 35(2.0) | 12 (34.3) | 23 (65.7) | 1.82 | 0.81−3.86 | 1.59 | 0.55−4.57 |

| -Asthma or sibilant rales | 207 (12.2) | 38 (18.4) | 169 (81.6) | 0.74 | 0.50−1.09 | 0.77 | 0.26−2.24 |

| -Other respiratory conditions | 84(4.5) | 16 (18.8) | 68 (81.0) | 1.19 | 0.83−1.72 | 0.93 | 0.33−1.99 |

| Breathing parameters and oxygenation at admission | |||||||

| Fraction of inspired O2 (FiO2) | 70 [50−100] | 80 [60−100] | 69 [50−100] | 1.01 | 1.0- 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.99−1.01 |

| O2 saturation (SpO2) | 96 [93−99] | 96 [93−99] | 96 [93−99] | 1.00 | 0.98−1.01 | 0.99 | 0.97−1.01 |

| Respiratory rate | 43 [30−59] | 40 [28−52] | 45 [30−60] | 0.98 | 0.97−0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98−1.00 |

| Heart rate | 152 [133−170] | 150 [130−165] | 152 [135−170] | 0.99 | 0.99−0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99−1.01 |

| SpO2/FiO2 | 137 [100−192] | 121 [99−160] | 147 [100−196] | 0.99 | 0.99−0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99−1.00 |

| Radiological findingsd | |||||||

| Normal | 49 (2.9) | 10 (20.4) | 39 (79.6) | 0.88 | 0.45−1.78 | 0.56 | 0.18−1.75 |

| Hyperinflation | 394 (23.2) | 55 (14) | 339 (86) | 0.48 | 0.35−0.66 | 0.88 | 0.55−1.41 |

| Condensation | 473 (27.8) | 76 (16.1) | 397 (83.9) | 0.57 | 0.43−0.75 | 0.69 | 0.43−1.11 |

| Interstitial infiltrate | 1135 (66.8) | 287 (25.3) | 848 (74.7) | 1.66 | 1.28−2.15 | 1.09 | 0.72−1.64 |

| Pneumothoraxf | 20 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (100.0) | ||||

| Pleural effusion | 55 (3.2) | 11 (16.9) | 54 (83.1) | 0.69 | 0.35−1.33 | 0.96 | 0.34−2.72 |

| Cardiomegaly | 51 (3) | 11 (21.5) | 40 (78.5) | 0.94 | 0.48−1.86 | 1.36 | 0.51−3.59 |

| Other | 166 (9.7) | 34 (20.5) | 132 (79.5) | 0.87 | 0.59−1.30 | 1.09 | 0.63−1.86 |

| Scores at admission | |||||||

| PIM3 likeliness | 0.57 [0.38−3.10] | 0.57 [0.39−1.40] | 0.59 [0.38−3.38] | 1.00 | 0.99−1.01 | 1.00 | 0.99−1.01 |

| Baseline FSS score | 6 (6−7) | 6 (6−7) | 6 (6−7) | 1.00 | 0.96−1.04 | 1.01 | 0.95−1.06 |

Mixed logistic regression model adjusted by country. aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; npIMV, non-prolonged invasive mechanical ventilation; OR, odds ratio; PIM3, Pediatric Index of Mortality version 3; pIMV, prolonged invasive mechanical ventilation; ref, reference; SpO2/FiO2, oxygen saturation to fraction of inspired oxygen ratio; bold indicates statistically significant values and subcategories.

The multivariate analysis proved that age <6 months, the presence of comorbidity, particularly bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and fungal isolation were independent factors associated with pIMV. Patients with asthma had less chances of being associated with pIMV (Table 1).

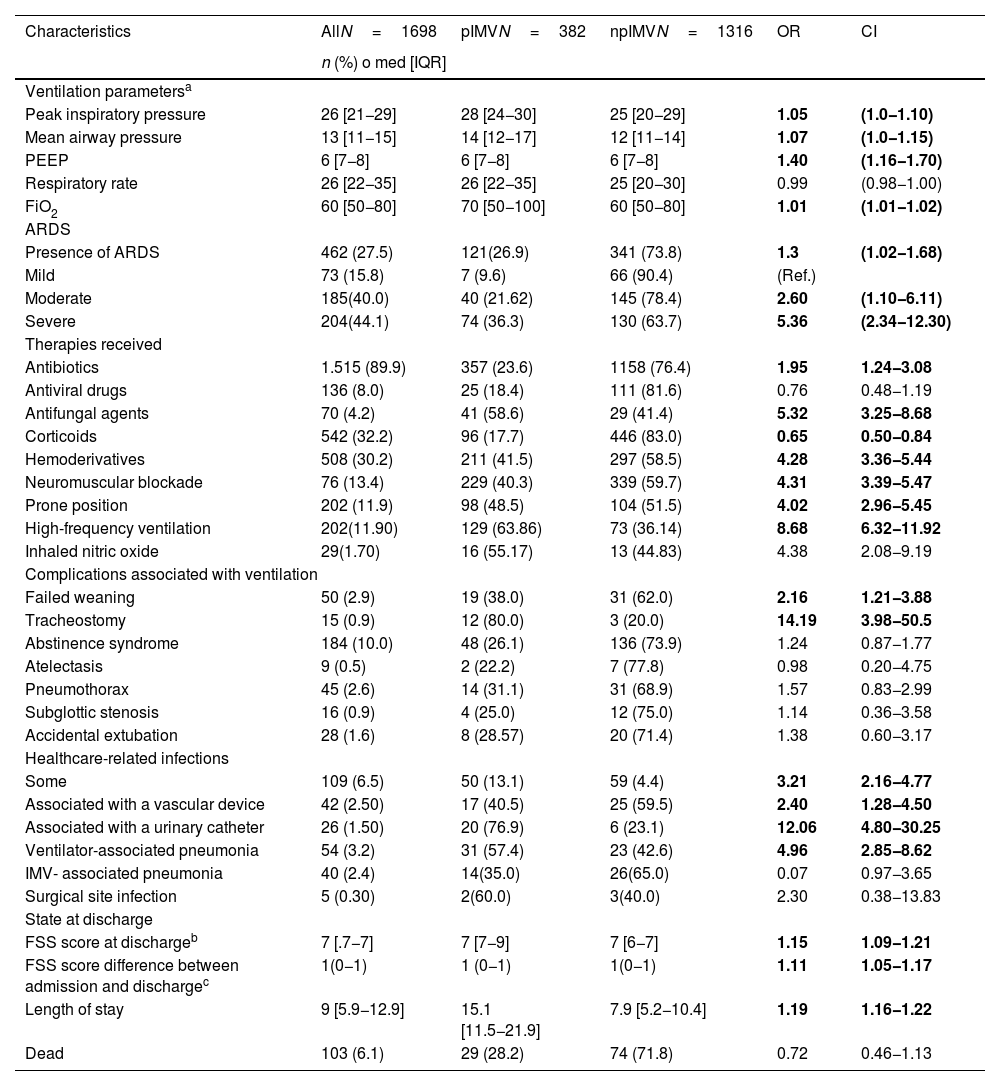

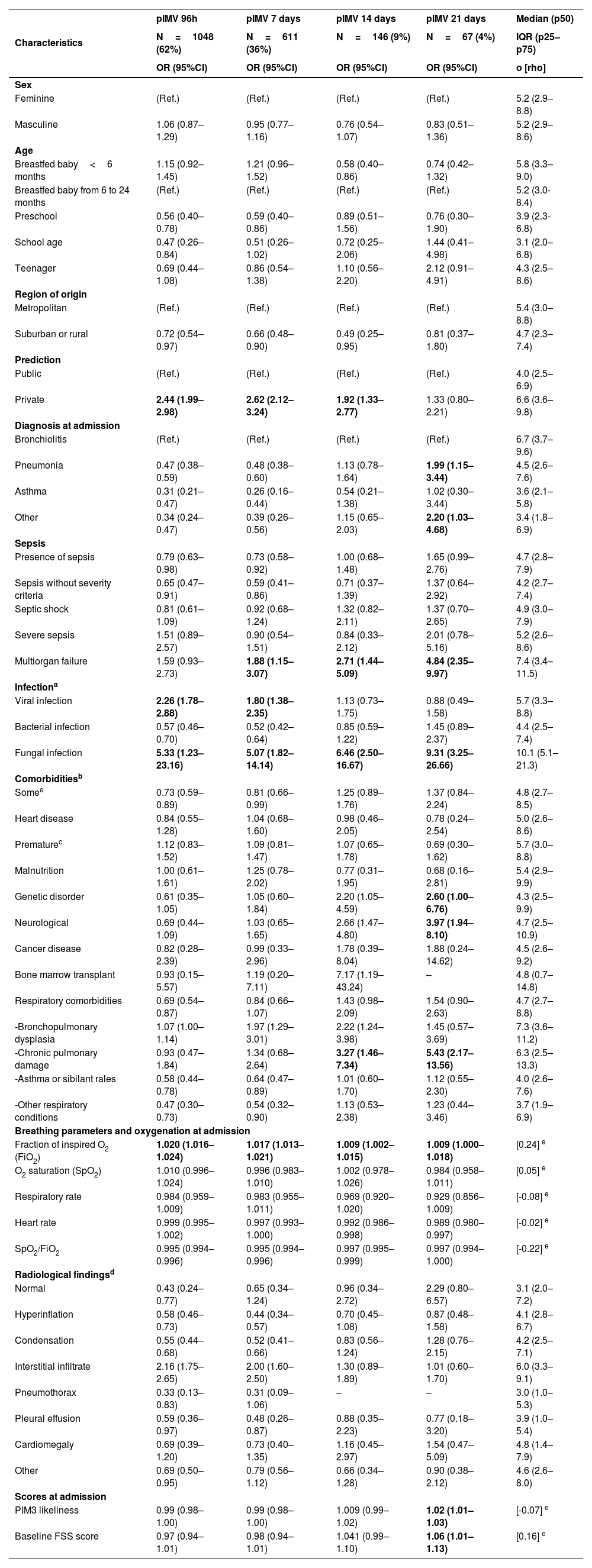

Characteristics of disease progression and length of stayThe characteristics of disease progression and length of stay are shown on Table 2. Bivariate comparisons for other cutoff timeframes described in the medical literature available, and the measure of central tendency and dispersion of ventilation time per factor are shown on Tables 3 and 4.

Factors associated with outcomes and length of stay at the PICU correlated to prolonged invasive mechanical ventilation after multivariate analysis.

| Characteristics | AllN=1698 | pIMVN=382 | npIMVN=1316 | OR | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) o med [IQR] | |||||

| Ventilation parametersa | |||||

| Peak inspiratory pressure | 26 [21−29] | 28 [24−30] | 25 [20−29] | 1.05 | (1.0−1.10) |

| Mean airway pressure | 13 [11−15] | 14 [12−17] | 12 [11−14] | 1.07 | (1.0−1.15) |

| PEEP | 6 [7−8] | 6 [7−8] | 6 [7−8] | 1.40 | (1.16−1.70) |

| Respiratory rate | 26 [22−35] | 26 [22−35] | 25 [20−30] | 0.99 | (0.98−1.00) |

| FiO2 | 60 [50−80] | 70 [50−100] | 60 [50−80] | 1.01 | (1.01−1.02) |

| ARDS | |||||

| Presence of ARDS | 462 (27.5) | 121(26.9) | 341 (73.8) | 1.3 | (1.02−1.68) |

| Mild | 73 (15.8) | 7 (9.6) | 66 (90.4) | (Ref.) | |

| Moderate | 185(40.0) | 40 (21.62) | 145 (78.4) | 2.60 | (1.10−6.11) |

| Severe | 204(44.1) | 74 (36.3) | 130 (63.7) | 5.36 | (2.34−12.30) |

| Therapies received | |||||

| Antibiotics | 1.515 (89.9) | 357 (23.6) | 1158 (76.4) | 1.95 | 1.24−3.08 |

| Antiviral drugs | 136 (8.0) | 25 (18.4) | 111 (81.6) | 0.76 | 0.48−1.19 |

| Antifungal agents | 70 (4.2) | 41 (58.6) | 29 (41.4) | 5.32 | 3.25−8.68 |

| Corticoids | 542 (32.2) | 96 (17.7) | 446 (83.0) | 0.65 | 0.50−0.84 |

| Hemoderivatives | 508 (30.2) | 211 (41.5) | 297 (58.5) | 4.28 | 3.36−5.44 |

| Neuromuscular blockade | 76 (13.4) | 229 (40.3) | 339 (59.7) | 4.31 | 3.39−5.47 |

| Prone position | 202 (11.9) | 98 (48.5) | 104 (51.5) | 4.02 | 2.96−5.45 |

| High-frequency ventilation | 202(11.90) | 129 (63.86) | 73 (36.14) | 8.68 | 6.32−11.92 |

| Inhaled nitric oxide | 29(1.70) | 16 (55.17) | 13 (44.83) | 4.38 | 2.08−9.19 |

| Complications associated with ventilation | |||||

| Failed weaning | 50 (2.9) | 19 (38.0) | 31 (62.0) | 2.16 | 1.21−3.88 |

| Tracheostomy | 15 (0.9) | 12 (80.0) | 3 (20.0) | 14.19 | 3.98−50.5 |

| Abstinence syndrome | 184 (10.0) | 48 (26.1) | 136 (73.9) | 1.24 | 0.87−1.77 |

| Atelectasis | 9 (0.5) | 2 (22.2) | 7 (77.8) | 0.98 | 0.20−4.75 |

| Pneumothorax | 45 (2.6) | 14 (31.1) | 31 (68.9) | 1.57 | 0.83−2.99 |

| Subglottic stenosis | 16 (0.9) | 4 (25.0) | 12 (75.0) | 1.14 | 0.36−3.58 |

| Accidental extubation | 28 (1.6) | 8 (28.57) | 20 (71.4) | 1.38 | 0.60−3.17 |

| Healthcare-related infections | |||||

| Some | 109 (6.5) | 50 (13.1) | 59 (4.4) | 3.21 | 2.16−4.77 |

| Associated with a vascular device | 42 (2.50) | 17 (40.5) | 25 (59.5) | 2.40 | 1.28−4.50 |

| Associated with a urinary catheter | 26 (1.50) | 20 (76.9) | 6 (23.1) | 12.06 | 4.80−30.25 |

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia | 54 (3.2) | 31 (57.4) | 23 (42.6) | 4.96 | 2.85−8.62 |

| IMV- associated pneumonia | 40 (2.4) | 14(35.0) | 26(65.0) | 0.07 | 0.97−3.65 |

| Surgical site infection | 5 (0.30) | 2(60.0) | 3(40.0) | 2.30 | 0.38−13.83 |

| State at discharge | |||||

| FSS score at dischargeb | 7 [.7−7] | 7 [7−9] | 7 [6−7] | 1.15 | 1.09−1.21 |

| FSS score difference between admission and dischargec | 1(0−1) | 1 (0−1) | 1(0−1) | 1.11 | 1.05−1.17 |

| Length of stay | 9 [5.9−12.9] | 15.1 [11.5−21.9] | 7.9 [5.2−10.4] | 1.19 | 1.16−1.22 |

| Dead | 103 (6.1) | 29 (28.2) | 74 (71.8) | 0.72 | 0.46−1.13 |

Bivariate analysis, aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ref, reference; npIMV, non-prolonged invasive mechanical ventilation; OR, odds ratio; pIMV, prolonged invasive mechanical ventilation; bold indicates statistically significant values and subcategories.

Bivariate analysis of the association between admission factors and different definitions of prolonged invasive mechanical ventilation (pIMV) in the medical literature currently available.

| Characteristics | pIMV 96h | pIMV 7 days | pIMV 14 days | pIMV 21 days | Median (p50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=1048 (62%) | N=611 (36%) | N=146 (9%) | N=67 (4%) | IQR (p25–p75) | |

| OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | o [rho] | |

| Sex | |||||

| Feminine | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | 5.2 (2.9–8.8) |

| Masculine | 1.06 (0.87–1.29) | 0.95 (0.77–1.16) | 0.76 (0.54–1.07) | 0.83 (0.51–1.36) | 5.2 (2.9–8.6) |

| Age | |||||

| Breastfed baby<6 months | 1.15 (0.92–1.45) | 1.21 (0.96–1.52) | 0.58 (0.40–0.86) | 0.74 (0.42–1.32) | 5.8 (3.3–9.0) |

| Breastfed baby from 6 to 24 months | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | 5.2 (3.0-8.4) |

| Preschool | 0.56 (0.40–0.78) | 0.59 (0.40–0.86) | 0.89 (0.51–1.56) | 0.76 (0.30–1.90) | 3.9 (2.3-6.8) |

| School age | 0.47 (0.26–0.84) | 0.51 (0.26–1.02) | 0.72 (0.25–2.06) | 1.44 (0.41–4.98) | 3.1 (2.0–6.8) |

| Teenager | 0.69 (0.44–1.08) | 0.86 (0.54–1.38) | 1.10 (0.56–2.20) | 2.12 (0.91–4.91) | 4.3 (2.5–8.6) |

| Region of origin | |||||

| Metropolitan | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | 5.4 (3.0–8.8) |

| Suburban or rural | 0.72 (0.54–0.97) | 0.66 (0.48–0.90) | 0.49 (0.25–0.95) | 0.81 (0.37–1.80) | 4.7 (2.3–7.4) |

| Prediction | |||||

| Public | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | 4.0 (2.5–6.9) |

| Private | 2.44 (1.99–2.98) | 2.62 (2.12–3.24) | 1.92 (1.33–2.77) | 1.33 (0.80–2.21) | 6.6 (3.6–9.8) |

| Diagnosis at admission | |||||

| Bronchiolitis | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | 6.7 (3.7–9.6) |

| Pneumonia | 0.47 (0.38–0.59) | 0.48 (0.38–0.60) | 1.13 (0.78–1.64) | 1.99 (1.15–3.44) | 4.5 (2.6–7.6) |

| Asthma | 0.31 (0.21–0.47) | 0.26 (0.16–0.44) | 0.54 (0.21–1.38) | 1.02 (0.30–3.44) | 3.6 (2.1–5.8) |

| Other | 0.34 (0.24–0.47) | 0.39 (0.26–0.56) | 1.15 (0.65–2.03) | 2.20 (1.03–4.68) | 3.4 (1.8–6.9) |

| Sepsis | |||||

| Presence of sepsis | 0.79 (0.63–0.98) | 0.73 (0.58–0.92) | 1.00 (0.68–1.48) | 1.65 (0.99–2.76) | 4.7 (2.8–7.9) |

| Sepsis without severity criteria | 0.65 (0.47–0.91) | 0.59 (0.41–0.86) | 0.71 (0.37–1.39) | 1.37 (0.64–2.92) | 4.2 (2.7–7.4) |

| Septic shock | 0.81 (0.61–1.09) | 0.92 (0.68–1.24) | 1.32 (0.82–2.11) | 1.37 (0.70–2.65) | 4.9 (3.0–7.9) |

| Severe sepsis | 1.51 (0.89–2.57) | 0.90 (0.54–1.51) | 0.84 (0.33–2.12) | 2.01 (0.78–5.16) | 5.2 (2.6–8.6) |

| Multiorgan failure | 1.59 (0.93–2.73) | 1.88 (1.15–3.07) | 2.71 (1.44–5.09) | 4.84 (2.35–9.97) | 7.4 (3.4–11.5) |

| Infectiona | |||||

| Viral infection | 2.26 (1.78–2.88) | 1.80 (1.38–2.35) | 1.13 (0.73–1.75) | 0.88 (0.49–1.58) | 5.7 (3.3–8.8) |

| Bacterial infection | 0.57 (0.46–0.70) | 0.52 (0.42–0.64) | 0.85 (0.59–1.22) | 1.45 (0.89–2.37) | 4.4 (2.5–7.4) |

| Fungal infection | 5.33 (1.23–23.16) | 5.07 (1.82–14.14) | 6.46 (2.50–16.67) | 9.31 (3.25–26.66) | 10.1 (5.1–21.3) |

| Comorbiditiesb | |||||

| Somee | 0.73 (0.59–0.89) | 0.81 (0.66–0.99) | 1.25 (0.89–1.76) | 1.37 (0.84–2.24) | 4.8 (2.7–8.5) |

| Heart disease | 0.84 (0.55–1.28) | 1.04 (0.68–1.60) | 0.98 (0.46–2.05) | 0.78 (0.24–2.54) | 5.0 (2.6–8.6) |

| Prematurec | 1.12 (0.83–1.52) | 1.09 (0.81–1.47) | 1.07 (0.65–1.78) | 0.69 (0.30–1.62) | 5.7 (3.0–8.8) |

| Malnutrition | 1.00 (0.61–1.61) | 1.25 (0.78–2.02) | 0.77 (0.31–1.95) | 0.68 (0.16–2.81) | 5.4 (2.9–9.9) |

| Genetic disorder | 0.61 (0.35–1.05) | 1.05 (0.60–1.84) | 2.20 (1.05–4.59) | 2.60 (1.00–6.76) | 4.3 (2.5–9.9) |

| Neurological | 0.69 (0.44–1.09) | 1.03 (0.65–1.65) | 2.66 (1.47–4.80) | 3.97 (1.94–8.10) | 4.7 (2.5–10.9) |

| Cancer disease | 0.82 (0.28–2.39) | 0.99 (0.33–2.96) | 1.78 (0.39–8.04) | 1.88 (0.24–14.62) | 4.5 (2.6–9.2) |

| Bone marrow transplant | 0.93 (0.15–5.57) | 1.19 (0.20–7.11) | 7.17 (1.19–43.24) | – | 4.8 (0.7–14.8) |

| Respiratory comorbidities | 0.69 (0.54–0.87) | 0.84 (0.66–1.07) | 1.43 (0.98–2.09) | 1.54 (0.90–2.63) | 4.7 (2.7–8.8) |

| -Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 1.07 (1.00–1.14) | 1.97 (1.29–3.01) | 2.22 (1.24–3.98) | 1.45 (0.57–3.69) | 7.3 (3.6–11.2) |

| -Chronic pulmonary damage | 0.93 (0.47–1.84) | 1.34 (0.68–2.64) | 3.27 (1.46–7.34) | 5.43 (2.17–13.56) | 6.3 (2.5–13.3) |

| -Asthma or sibilant rales | 0.58 (0.44–0.78) | 0.64 (0.47–0.89) | 1.01 (0.60–1.70) | 1.12 (0.55–2.30) | 4.0 (2.6–7.6) |

| -Other respiratory conditions | 0.47 (0.30–0.73) | 0.54 (0.32–0.90) | 1.13 (0.53–2.38) | 1.23 (0.44–3.46) | 3.7 (1.9–6.9) |

| Breathing parameters and oxygenation at admission | |||||

| Fraction of inspired O2 (FiO2) | 1.020 (1.016–1.024) | 1.017 (1.013–1.021) | 1.009 (1.002–1.015) | 1.009 (1.000–1.018) | [0.24] e |

| O2 saturation (SpO2) | 1.010 (0.996–1.024) | 0.996 (0.983–1.010) | 1.002 (0.978–1.026) | 0.984 (0.958–1.011) | [0.05] e |

| Respiratory rate | 0.984 (0.959–1.009) | 0.983 (0.955–1.011) | 0.969 (0.920–1.020) | 0.929 (0.856–1.009) | [-0.08] e |

| Heart rate | 0.999 (0.995–1.002) | 0.997 (0.993–1.000) | 0.992 (0.986–0.998) | 0.989 (0.980–0.997) | [-0.02] e |

| SpO2/FiO2 | 0.995 (0.994–0.996) | 0.995 (0.994–0.996) | 0.997 (0.995–0.999) | 0.997 (0.994–1.000) | [-0.22] e |

| Radiological findingsd | |||||

| Normal | 0.43 (0.24–0.77) | 0.65 (0.34–1.24) | 0.96 (0.34–2.72) | 2.29 (0.80–6.57) | 3.1 (2.0–7.2) |

| Hyperinflation | 0.58 (0.46–0.73) | 0.44 (0.34–0.57) | 0.70 (0.45–1.08) | 0.87 (0.48–1.58) | 4.1 (2.8–6.7) |

| Condensation | 0.55 (0.44–0.68) | 0.52 (0.41–0.66) | 0.83 (0.56–1.24) | 1.28 (0.76–2.15) | 4.2 (2.5–7.1) |

| Interstitial infiltrate | 2.16 (1.75–2.65) | 2.00 (1.60–2.50) | 1.30 (0.89–1.89) | 1.01 (0.60–1.70) | 6.0 (3.3–9.1) |

| Pneumothorax | 0.33 (0.13–0.83) | 0.31 (0.09–1.06) | – | – | 3.0 (1.0–5.3) |

| Pleural effusion | 0.59 (0.36–0.97) | 0.48 (0.26–0.87) | 0.88 (0.35–2.23) | 0.77 (0.18–3.20) | 3.9 (1.0–5.4) |

| Cardiomegaly | 0.69 (0.39–1.20) | 0.73 (0.40–1.35) | 1.16 (0.45–2.97) | 1.54 (0.47–5.09) | 4.8 (1.4–7.9) |

| Other | 0.69 (0.50–0.95) | 0.79 (0.56–1.12) | 0.66 (0.34–1.28) | 0.90 (0.38–2.12) | 4.6 (2.6–8.0) |

| Scores at admission | |||||

| PIM3 likeliness | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 1.009 (0.99–1.02) | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | [-0.07] e |

| Baseline FSS score | 0.97 (0.94–1.01) | 0.98 (0.94–1.01) | 1.041 (0.99–1.10) | 1.06 (1.01–1.13) | [0.16] e |

Bivariate analysis using a simple logistic regression model. CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PIM3, Pediatric Index of Mortality version 3; pIMV, prolonged invasive mechanical ventilation; ref, reference; SpO2/FiO2, oxygen saturation to fraction of inspired oxygen ratio; bold indicates statistically significant values and subcategories. In red, all statistically significant values > 1; in green, statistically significant values < 1.

a. More than 1 etiology can be attributed to a patient; b. More than 1 comorbidity can be attributed to a patient; c. Prematurity, defined as gestational age < 37 weeks; d. More than 1 radiological finding can be attributed to a patient; e. Spearman's correlation coefficient (rho) for the comparison between continuous variables and ventilation time.

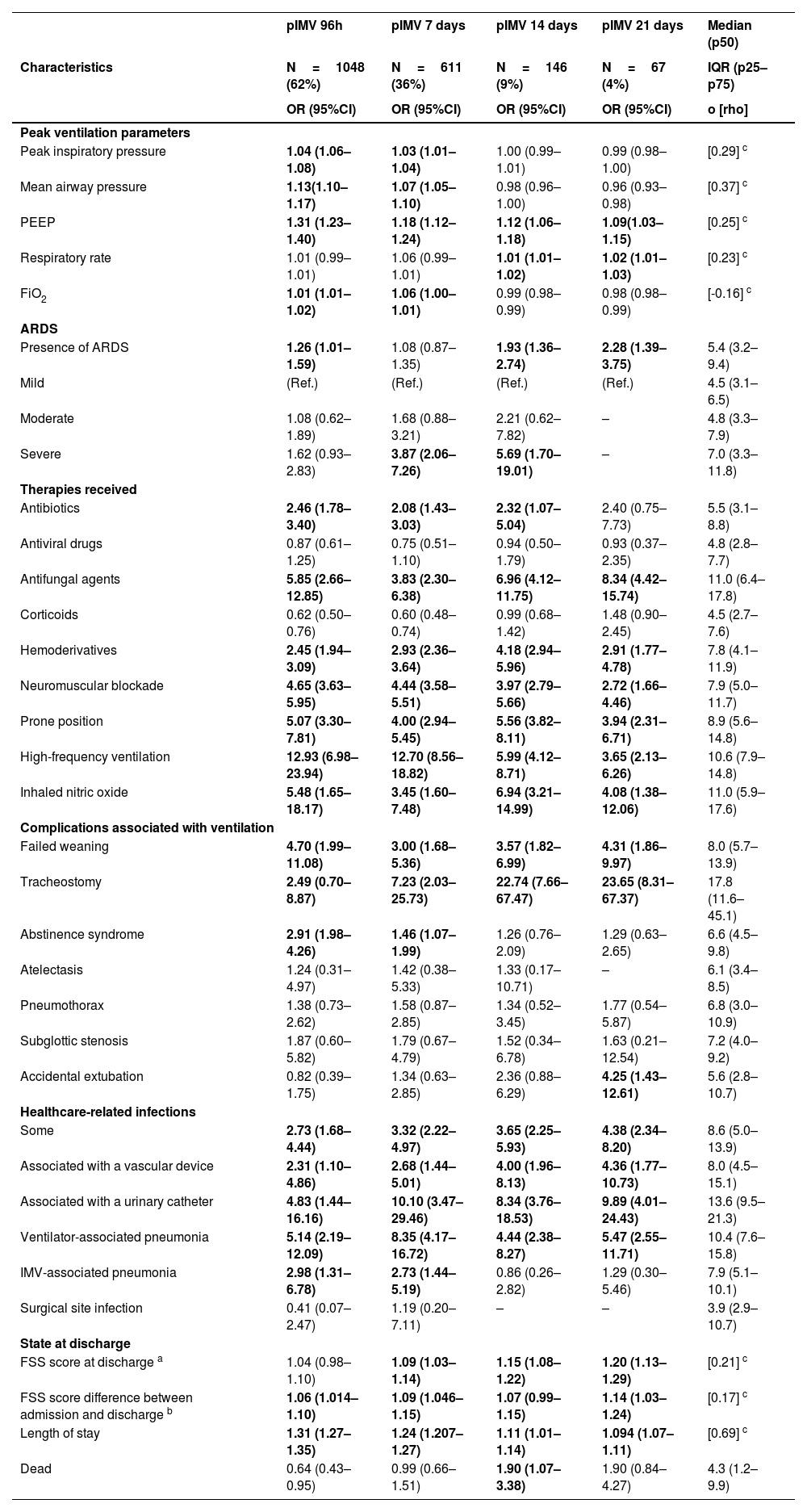

Bivariate analysis of the association between outcome factors and length of stay at the PICU and different definitions of prolonged invasive mechanical ventilation (pIMV) in the medical literature currently available.

| Characteristics | pIMV 96h | pIMV 7 days | pIMV 14 days | pIMV 21 days | Median (p50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=1048 (62%) | N=611 (36%) | N=146 (9%) | N=67 (4%) | IQR (p25–p75) | |

| OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | o [rho] | |

| Peak ventilation parameters | |||||

| Peak inspiratory pressure | 1.04 (1.06–1.08) | 1.03 (1.01–1.04) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | [0.29] c |

| Mean airway pressure | 1.13(1.10–1.17) | 1.07 (1.05–1.10) | 0.98 (0.96–1.00) | 0.96 (0.93–0.98) | [0.37] c |

| PEEP | 1.31 (1.23–1.40) | 1.18 (1.12–1.24) | 1.12 (1.06–1.18) | 1.09(1.03–1.15) | [0.25] c |

| Respiratory rate | 1.01 (0.99–1.01) | 1.06 (0.99–1.01) | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | [0.23] c |

| FiO2 | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | 1.06 (1.00–1.01) | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | 0.98 (0.98–0.99) | [-0.16] c |

| ARDS | |||||

| Presence of ARDS | 1.26 (1.01–1.59) | 1.08 (0.87–1.35) | 1.93 (1.36–2.74) | 2.28 (1.39–3.75) | 5.4 (3.2–9.4) |

| Mild | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | 4.5 (3.1–6.5) |

| Moderate | 1.08 (0.62–1.89) | 1.68 (0.88–3.21) | 2.21 (0.62–7.82) | – | 4.8 (3.3–7.9) |

| Severe | 1.62 (0.93–2.83) | 3.87 (2.06–7.26) | 5.69 (1.70–19.01) | – | 7.0 (3.3–11.8) |

| Therapies received | |||||

| Antibiotics | 2.46 (1.78–3.40) | 2.08 (1.43–3.03) | 2.32 (1.07–5.04) | 2.40 (0.75–7.73) | 5.5 (3.1–8.8) |

| Antiviral drugs | 0.87 (0.61–1.25) | 0.75 (0.51–1.10) | 0.94 (0.50–1.79) | 0.93 (0.37–2.35) | 4.8 (2.8–7.7) |

| Antifungal agents | 5.85 (2.66–12.85) | 3.83 (2.30–6.38) | 6.96 (4.12–11.75) | 8.34 (4.42–15.74) | 11.0 (6.4–17.8) |

| Corticoids | 0.62 (0.50–0.76) | 0.60 (0.48–0.74) | 0.99 (0.68–1.42) | 1.48 (0.90–2.45) | 4.5 (2.7–7.6) |

| Hemoderivatives | 2.45 (1.94–3.09) | 2.93 (2.36–3.64) | 4.18 (2.94–5.96) | 2.91 (1.77–4.78) | 7.8 (4.1–11.9) |

| Neuromuscular blockade | 4.65 (3.63–5.95) | 4.44 (3.58–5.51) | 3.97 (2.79–5.66) | 2.72 (1.66–4.46) | 7.9 (5.0–11.7) |

| Prone position | 5.07 (3.30–7.81) | 4.00 (2.94–5.45) | 5.56 (3.82–8.11) | 3.94 (2.31–6.71) | 8.9 (5.6–14.8) |

| High-frequency ventilation | 12.93 (6.98–23.94) | 12.70 (8.56–18.82) | 5.99 (4.12–8.71) | 3.65 (2.13–6.26) | 10.6 (7.9–14.8) |

| Inhaled nitric oxide | 5.48 (1.65–18.17) | 3.45 (1.60–7.48) | 6.94 (3.21–14.99) | 4.08 (1.38–12.06) | 11.0 (5.9–17.6) |

| Complications associated with ventilation | |||||

| Failed weaning | 4.70 (1.99–11.08) | 3.00 (1.68–5.36) | 3.57 (1.82–6.99) | 4.31 (1.86–9.97) | 8.0 (5.7–13.9) |

| Tracheostomy | 2.49 (0.70–8.87) | 7.23 (2.03–25.73) | 22.74 (7.66–67.47) | 23.65 (8.31–67.37) | 17.8 (11.6–45.1) |

| Abstinence syndrome | 2.91 (1.98–4.26) | 1.46 (1.07–1.99) | 1.26 (0.76–2.09) | 1.29 (0.63–2.65) | 6.6 (4.5–9.8) |

| Atelectasis | 1.24 (0.31–4.97) | 1.42 (0.38–5.33) | 1.33 (0.17–10.71) | – | 6.1 (3.4–8.5) |

| Pneumothorax | 1.38 (0.73–2.62) | 1.58 (0.87–2.85) | 1.34 (0.52–3.45) | 1.77 (0.54–5.87) | 6.8 (3.0–10.9) |

| Subglottic stenosis | 1.87 (0.60–5.82) | 1.79 (0.67–4.79) | 1.52 (0.34–6.78) | 1.63 (0.21–12.54) | 7.2 (4.0–9.2) |

| Accidental extubation | 0.82 (0.39–1.75) | 1.34 (0.63–2.85) | 2.36 (0.88–6.29) | 4.25 (1.43–12.61) | 5.6 (2.8–10.7) |

| Healthcare-related infections | |||||

| Some | 2.73 (1.68–4.44) | 3.32 (2.22–4.97) | 3.65 (2.25–5.93) | 4.38 (2.34–8.20) | 8.6 (5.0–13.9) |

| Associated with a vascular device | 2.31 (1.10–4.86) | 2.68 (1.44–5.01) | 4.00 (1.96–8.13) | 4.36 (1.77–10.73) | 8.0 (4.5–15.1) |

| Associated with a urinary catheter | 4.83 (1.44–16.16) | 10.10 (3.47–29.46) | 8.34 (3.76–18.53) | 9.89 (4.01–24.43) | 13.6 (9.5–21.3) |

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia | 5.14 (2.19–12.09) | 8.35 (4.17–16.72) | 4.44 (2.38–8.27) | 5.47 (2.55–11.71) | 10.4 (7.6–15.8) |

| IMV-associated pneumonia | 2.98 (1.31–6.78) | 2.73 (1.44–5.19) | 0.86 (0.26–2.82) | 1.29 (0.30–5.46) | 7.9 (5.1–10.1) |

| Surgical site infection | 0.41 (0.07–2.47) | 1.19 (0.20–7.11) | – | – | 3.9 (2.9–10.7) |

| State at discharge | |||||

| FSS score at discharge a | 1.04 (0.98–1.10) | 1.09 (1.03–1.14) | 1.15 (1.08–1.22) | 1.20 (1.13–1.29) | [0.21] c |

| FSS score difference between admission and discharge b | 1.06 (1.014–1.10) | 1.09 (1.046–1.15) | 1.07 (0.99–1.15) | 1.14 (1.03–1.24) | [0.17] c |

| Length of stay | 1.31 (1.27–1.35) | 1.24 (1.207–1.27) | 1.11 (1.01–1.14) | 1.094 (1.07–1.11) | [0.69] c |

| Dead | 0.64 (0.43–0.95) | 0.99 (0.66–1.51) | 1.90 (1.07–3.38) | 1.90 (0.84–4.27) | 4.3 (1.2–9.9) |

Bivariate analysis using a simple logistic regression model. CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; pIMV, prolonged invasive mechanical ventilation; ref, reference; in red, all statistically significant values > 1; in green, statistically significant values < 1.

a. FSS score at admission with 489 missing pieces of information; b. Difference between admission and discharge with 502 missing pieces of information. c. Spearman's correlation coefficient for the comparison between continuous variables and ventilation time.

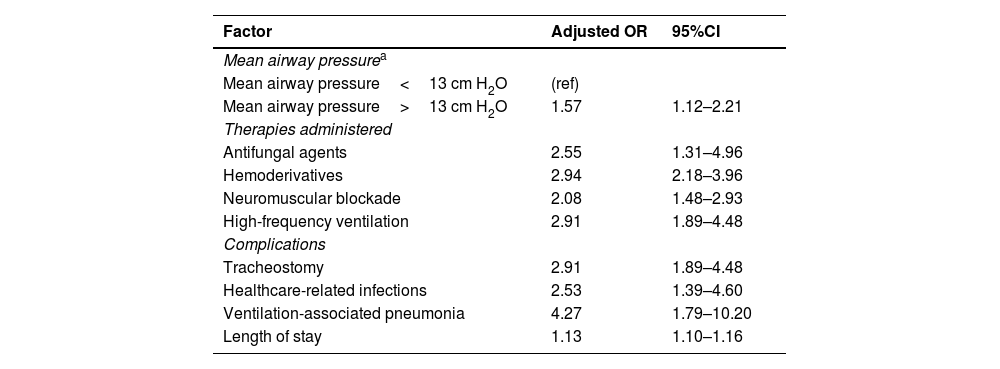

The multivariate model showed that the pIMV group required more antifungals, blood products, neuromuscular blockade, and high-frequency ventilation. Similarly, they also had a higher risk of healthcare-associated infections, particularly ventilator-associated pneumonia, and need for tracheostomy. It was also identified that patients who required a mean airway pressure >13cm H2O during the hospital stay (Table 5) had longer lengths of stay without any mortality differences being reported.

Factors associated with outcome and length of stay at the PICU and correlated with prolonged invasive mechanical ventilation after multivariate analysis.

| Factor | Adjusted OR | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|

| Mean airway pressurea | ||

| Mean airway pressure<13 cm H2O | (ref) | |

| Mean airway pressure>13 cm H2O | 1.57 | 1.12–2.21 |

| Therapies administered | ||

| Antifungal agents | 2.55 | 1.31–4.96 |

| Hemoderivatives | 2.94 | 2.18–3.96 |

| Neuromuscular blockade | 2.08 | 1.48–2.93 |

| High-frequency ventilation | 2.91 | 1.89–4.48 |

| Complications | ||

| Tracheostomy | 2.91 | 1.89–4.48 |

| Healthcare-related infections | 2.53 | 1.39–4.60 |

| Ventilation-associated pneumonia | 4.27 | 1.79–10.20 |

| Length of stay | 1.13 | 1.10–1.16 |

Mixed logistic regression model adjusted by country. aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ref, reference; bold indicates statistically significant values and subcategories.

FSS at discharge, and difference of FSS between admission and discharge not included due to missing pieces of information.

The main outcome of the analysis in this contemporary multicenter cohort of patients on IMV was the identification of 9 days as a differential cutoff timeframe that contributes to the definition of prolonged invasive mechanical ventilation (pIMV) based on relevant outcomes in the routine clinical practice: a higher percentage of multiorgan dysfunction, presence of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), higher rate of healthcare-associated infections, and increased use of adjuvant therapies like neuromuscular blockade, antibiotics, prone position, and HFOV in those with on IMV for more than 9 days.

In pediatrics, there is no consensus on pIMV, and evidence for an appropriate definition is scarce. This knowledge gap leads to significant variability in the interpretation of results across different studies. The most commonly used definitions in the medical literature available of pIMV include the requirement of invasive mechanical ventilation for over 72h,19–21 7 days,8,22–26, 14 days,27–29 and up to 21 days.6,30,31 In this study of the LARed cohort, we used a different approach. pIMV was defined as a duration >9 days based on the 75th percentile of the dispersion statistic including 22.5% of the cases in this group.

The frequency of pIMV in the cohort studied is difficult to compare to other reports due to differences in definitions and patient heterogeneity.32 In our cohort, 73.6% of the patients were on IMV longer for over 72h, 36% for over 7 days, 8.5% for over 14 days, and 3.9% for over 21 days, similar data to the findings from other cohorts of patients with ARF.22–24,27–31 Similarly, we obtained a median course of ventilation of 5.23 days (2.92–8.62 days), similar to the group with mild ARDS from the PARDIE study with a median course of ventilation of 5.9 days (4.0−10.2 days).33

However, in this homogeneous cohort of patients with acute respiratory failure, we found that age <6 months and the presence of comorbidities, specifically bronchopulmonary dysplasia, were early risk factors of pIMV. Other studies in general ICU populations have also described that breastfed babies, premature infants or the presence of comorbidities are associated with pIMV (6–8). Interestingly enough, our result showed a negative correlation between asthma as the primary diagnosis leading to IMV and pIMV. The duration of ventilatory support was shorter in patients with asthma compared to those with bronchiolitis and pneumonia, which is similar to the findings reported in other cohort.34–37 This could be explained by the underlying pathophysiological mechanism, which often tends to be reversed within a short period of time in most patients with appropriate therap.37–39

It has been reported that bacterial coinfection in patients with respiratory syncytial virus infection leads to a longer course of mechanical ventilation.40 In our study, we did not find an association between bacterial or viral etiology of infection and pIMV. However, the decision to initiate antibiotic therapy was associated with pIMV in the univariate analysis, which could be considered as an indirect marker of sepsis or infection even in the absence of a positive culture. The diagnosis of fungal infection did show a strong association with pIMV.

The correlation between high scores in these severity scales as predictors of prolonged ventilation is controversial. Payen et al. found an association between the PRISM score and pIMV.7 In our study, we used the PIM3 scale and did not find any associations with pIMV, which is indicative that the most severely ill patient at the time of admission does not necessarily need to spend more time on IMV.

Respiratory system dysfunction occurred more frequently in pIMV with a higher number of cases of ARDS and greater need for ventilatory support. However, only a mean airway pressure >13cm H2O had a significant association in the multivariate analysis. Unlike other series, we found no association between pIMV and the degree of hypoxemia, but rather with the use of therapies like neuromuscular blockade and high-frequency ventilation. The pIMV group required more blood products, which is similar to what has been described in a general PICU cohort by Monteverde et al.6

In the multivariate analysis, we found an association between pIMV and healthcare-associated infections, particularly ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). This has also been reported in the general PICU population and in post-cardiac surgery patient.6 Other studies have demonstrated higher mortality rates in patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation beyond the usual average duration. Mortality rate associated with pIMV was 7%, which was not significantly higher compared to that reported in the cohort. However, pIMV was associated with longer lengths of stay and need for tracheostomy. Patients with pIMV had a lower Functional Status Scale (FSS) score when they were discharged from the PICU. Functional status scales have not been reported in previous pIMV cohorts. However, they are clinically important outcomes that assess not only acute-phase mortality but also the effect on the patients’ quality of life.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, due to the lack of a consensus definition for prolonged mechanical ventilation in pediatrics, we chose to use a statistical definition based on the distribution of our population. While we acknowledge that this selection may be considered arbitrary, it allowed us to accurately characterize a significant subgroup of children with prolonged ventilation and obtain clinically relevant results. However, we should mention that the applicability of these findings to other series or cohorts can be limited, and further validation through replication of our findings in other cohorts is required. Secondly, a key limitation of the study is the lack of access to the temporary nature of events beyond the 9-day mark on invasive mechanical ventilation due to the way the database was built. As a result, we were unable to establish a causal order with the available data. Thirdly, our study is retrospective and based on the secondary analysis of a cohort of patients with ARF, which limits the analysis to the variables present in the database. In addition, the duration of mechanical ventilation and other outcomes may be influenced by the different medical practice of the different centers involved. To mitigate this, we used an adjusted mixed logistic regression model. A fourth significant limitation of our study is the lack of clinical information when patients were intubated. Including this data would have allowed a more precise study of the association between prolonged ventilation and other risk factors and clinical outcomes. However, due to the way the information was collected in the database, we only had access to data on the admission of patients to the pediatric intensive care unit. Finally, we should mention that the association of factors does not imply causality. Therefore, our results should be interpreted with caution and not used to draw definitive conclusions on the association between prolonged ventilation and admission risk factors or subsequent events in patients with ARF.

ConclusionsIn our study, we saw that certain factors at admission, during disease progression, and during the stay at the PICU) are associated with prolonged mechanical ventilation, defined as a duration >75th percentile of the population (9 days). The results obtained in this study would allow us to intervene in modifiable risk factors and promote earlier weaning from mechanical ventilation to prevent complications and negative outcomes. Our data can be used to propose a definition of prolonged mechanical ventilation and serve as a metric of strategies to improve quality healthcare. Further research is needed to confirm these relations and, particularly, to establish whether there is an association between prolonged mechanical ventilation and the development of new morbidities.

Authors’ contributionJuan Sebastian Barajas-Romero, Pablo Vásquez-Hoyos, Sebastian Gonzalez-Dambrauskas, Franco Díaz, and Pietro Pietroboni participated in the study idea and design.

Pablo Vásquez-Hoyos, Rosalba Pardo, Juan Camilo Jaramillo-Bustamante, Regina Grigolli, Nicolas Monteverde-Fernández, Roberto Jabornisky, Pablo Cruces, Adriana Wegner, and Pietro Pietroboni participated in data curation.

Juan Sebastian Barajas-Romero, Pablo Vásquez-Hoyos, Sebastian Gonzalez-Dambrauskas, and Franco Díaz were responsible for the analysis and interpretation of data and drafting of the manuscript.

All authors contributed to the critical review of the intellectual content and final approval of the manuscript version to be published.

To the entire group of researchers of LARed Network who make this type of analysis possible.

Argentina

(AR) Hospital Juan Pablo II, Corrientes: Roberto Jabornisky, Fernando Español, Silvina Muzzio.

(AR) Hospital Regional Olga Stucky de Rizzi, Reconquista, Santa Fe: Alejandro Mansur, Evelin Cidral, Carlos Rodriguez, Roberto Jabornisky.

(AR) Hospital Durand, Bueno Aires: Analia Fernández, Diego Vinciguerra, Jorgelina Loyoco.

(AR) Hospital Pediátrico Alexander Fleming, Mendoza: Diego Aranda, Javier Figueroa, Patricia Correa.

Bolivia

(BO) Caja Nacional de Salud, La Paz: Antonio Bravo.

(BO) Hospital Materno Infantil Boliviano Japonés, Trinidad: Miguel Céspedes Lesczinsky, Zurama Velasco.

(BO) Hospital Regional San Juan de Dios, Tarija: Nils Casson Rodriguez, Estela Perales Ibañez

(BO) Hospital del Niño Dr. Ovidio Aliaga Uría, La Paz: Vladimir Aguilera Avendaño, Alfredo Rodríguez Vargas, Miguel Quispe Huanca, Gregorio Mariscal Quenta.

Brazil

(BR) Hospital Infantil Sabará, San Pablo: Andrea Aparecida Freitas Souza, Thais Oliveira Franco, Nelson Kazunobu Horigoshi, Regina Grigolli Cesar.

Chile

(CL) Complejo Asistencial Dr. Víctor Ríos Ruíz Los Ángeles, Diego Aranguiz Quintanilla, Juan Sepúlveda Sepúlveda, Ivette Padilla Maldonado

(CL) Hospital Complejo Asistencial Dr. Sotero del Rio, Santiago: Adriana Wegner, Pamela Céspedes.

(CL) Hospital Clínico Metropolitano La Florida, Santiago: Alejandro Donoso, María José Núñez Sanchez

(CL) Hospital El Carmen Dr. Luis Valentín Ferrada, Maipú: Pablo Cruces, Franco Díaz, Tamara Córdova.

(CL) Hospital Padre Hurtado, Santiago: Francisca Castro Zamorano, Javier Varela, Ricardo Carvajal Veas.

(CL) Hospital Luis Calvo Mackenna, Santiago: Carlos Acuña, Carolina Chandia, Jecar Neghme.

(CL) Hospital Regional de Antofagasta, Antofagasta: Pietro Pietroboni Fuster.

Colombia

(CO) Clínica Infantil de Colsubsidio, Bogotá: Alexandra Jimenez, Rosalba Pardo.

(CO) Hospital General de Medellín Luz Castro de Gutiérrez E.S.E. Medellín: Juan Camilo Jaramillo-Bustamante, Yúrika Paola López Alarcón.

(CO) Sociedad de Cirugía de Bogotá Hospital de San José, Bogotá: Pablo Vásquez-Hoyos.

(CO) Fundación Valle del Lili, Cali: Carlos Reina, Ruben Lasso, Sandra Concha.

(CO) Hospital Susana Lopez de Valencia, Popayán: Eliana Zemanate.

(CO) Hospital Universitario San Vicente Fundación, Medellín: Francisco Javier Montoya Ochoa, Andrea Betancur Franco.

(CO) Clínica UROS, Neiva: Boris Dussan, Ivan Ardila, Jennifer Silva.

Costa Rica

(CR) Hospital Nacional de Niños, San Jose: Ericka Ureña Chavarría, Jose Rosales Fernandez, Silvia Sanabria Fonseca.

Ecuador

(EC) Hospital Ingles, Quito: Maria Parada.

(EC) Hospital de Especialidades Carlos Andrade Marín, Quito: Andres Salazar, Jaime Fárez.

Suriname

(SR) Academic Pediatric Center Suriname Hospital Paramaribo, Paramaribo: Aartie Nannan-Toekoen, Juliana Amadu, Ragna Wolf.

Uruguay

(UY) Medica Uruguaya (MUCAM), Montevideo: Nicolas Monteverde-Fernandez

(UY) COMEPA (Corporación Médica de Paysandú), Paysandú: Luis Martínez, Silvia Dubra..

(UY) Asociacion Española: Alicia Fernández, Rodrigo Franchi.

(UY) Hospital Regional Salto, Salto: Luis Pedrozo, Alejandro Franco.

(UY) Círculo Católico de Obreros del Uruguay, Montevideo: Ema Benech, Mónica Carro.

(UY) Dirección Nacional de Sanidad Policial -Hospital Policial, Montevideo: Mercedes Ruibal, Andrea Iroa, Raúl Navatta, Magalí España.

(UY) Casa de Galicia, Montevideo: Alberto Serra, Fátima Varela, Bernardo Alonso.

(UY) Hospital Regional de Tacuarembó, Tacuarembó: Jorge Pastorini, Soledad Menta, Laura Madruga.

(UY) Hospital Central de las FFAA, Montevideo: Cristina Courtie, Javier Martínez, Krystel Cantirán.

(UY) CAMDEL (Cooperativa Asistencial Medica de Lavalleja): Luis Castro, Patricia Clavijo, Argelia Cantera.

(UY) COMECA (Cooperativa Medica de Canelones), Canelones: Bernardo Alonso, María Jose Caggiano, Carolina Talasimov.

(UY) Sanatorio SEMM-Mautone, Montevideo: Karina Etulain, Maria Parada, Nora Mouta, Maria José Corbo.

(UY) Hospital Evangélico del Uruguay, Montevideo: Eugenia Amaya, Verónica Etchevarren, Cecilia Mislej.