To determine the incidence of primary caregiver burden in a cohort of family members of critically ill patients admitted to ICU and to identify risk factors related to its development in both the patient and the family member.

DesignProspective observational cohort study was conducted for 24 months.

SettingHospital Universitario Clínico San Cecilio, Granada.

PatientsThe sample was the primary caregivers of all patients with risk factors for development of PICS (Post-Intensive Care Syndrome).

InterventionsThe follow-up protocol consisted of evaluation 3 months after discharge from the ICU in a specific consultation.

Main variables of interestThe scales used in patients were Barthel, SF-12, HADS, Pfeiffer, IES-6 and in relatives the Apgar and Zarit.

ResultsA total of 93 patients and caregivers were included in the follow-up. 15 relatives did not complete the follow-up questionnaires and were excluded from the study. The incidence of PICS-F (Family Post Intensive Care Syndrome) defined by the presence of primary caregiver burden in our cohort of patients is 34.6% (n=27), 95% CI 25.0−45.7. The risk factors for the development of caregiver burden are the presence of physical impairment, anxiety or post-traumatic stress in the patient, with no relationship found with the characteristics studied in the family member.

ConclusionsOne out of 3 relatives of patients with risk factors for the development of PICS presents at 3 months caregiver burden. This is related to factors dependent on the patient's state of health.

Determinar la incidencia de la sobrecarga del cuidador principal en una cohorte de familiares de pacientes críticos ingresados en UCI e identificar los factores de riesgo relacionados con su desarrollo tanto en el paciente como en el familiar.

DiseñoEstudio de cohortes observacional prospectivo durante 24 meses.

ÁmbitoHospital Universitario Clínico San Cecilio de Granada.

PacientesLa muestra estuvo compuesta por los cuidadores principales de todos los pacientes con factores de riesgo para el desarrollo de SPCI (Síndrome Post-Cuidados Intensivos).

IntervencionesEl protocolo de seguimiento consistió en la evaluación a los 3 meses del alta de la UCI en una consulta específica.

Variables de interés principalesLas escalas utilizadas fueron Barthel, SF-12, HADS, Pfeiffer, IES-6, Apgar y Zarit.

ResultadosUn total de 93 pacientes y cuidadores fueron incluidos en el seguimiento. 15 cuidadores no completaron los cuestionarios de seguimiento y fueron excluidos del estudio. La incidencia de PICS-F (Síndrome Post-Cuidados Intensivos Familiar) definido por la presencia de sobrecarga del cuidador en nuestra cohorte es del 34,6% (n=27), IC 95% 25,0–45,7. Los factores de riesgo para el desarrollo del mismo son la presencia de deterioro físico, ansiedad o estrés postraumático en el paciente, no encontrándose relación con las características estudiadas en el familiar.

ConclusionesUno de cada 3 familiares de pacientes con factores de riesgo para el desarrollo de SPCI presenta a los 3 meses sobrecarga del cuidador, relacionándose con factores dependientes del estado de salud del paciente.

A continuum of care for patients and families after critical illness, extending from the intensive care unit (ICU) to community or primary care, must become the standard of care. Transparent and public reporting of long-term ICU outcomes is fundamental for obtaining informed consent to initiate and continue ICU treatment, aligning care with patient and family values, and ensuring accountability for the high human and financial costs of these outcomes.1

It is increasingly recognized that the consequences of critical illness also place considerable strain on the families of ICU survivors, who often bear the burden of high levels of informal care. The term Post-intensive Care Family Syndrome (PICS-F) is considered to be the family member's response to the stress caused by the ICU admission of a loved one.2 It includes symptoms experienced by family members during there loved one's critical illness as well as those occurring after discharge from the ICU.3 The most common symptoms of relatives of critically ill patients include difficulty falling asleep, anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress syndrome.4

It is now known that between 25–50% of patients who survive ICU admission will need family support for care.5 The psychological and financial impact of caring for ICU survivors resembles that of the burden of care for a chronic illness.6 Psychological morbidity may persist for months or even years after the ICU discharge of a loved one.7,8

One of the main sources of stress is reported to be the interaction between the health care team and family members. According to the literature, the family of the critically ill patient experiences specific needs during their stay in the ICU. These ones become relevant from a more holistic view of the patient in which the family is also considered as a subject of attention and care. Numerous studies have been published on the needs of the family in the ICU; particularly those related to security and information have been described as the most important. It has been observed that there is a negative difference between the degree of importance and satisfaction in most of the needs of the family of critically ill patients.9 This highlights the importance of properly identifying the issues in the patient's medical care to which the family member considers most important.

The aim of the present study is to determine the incidence of primary caregiver burden as PICS-F in a cohort of family members of critically ill patients and to identify risk factors related to its development in both the patient and the family member.

Patients and methodsWe design a prospective observational cohort study during 24 months, from January 2019 to January 2021. The ICU of our University Hospital has 20 beds (six for cardiovascular and fourteen for polyvalent patients) and an average of 1200 admissions per year.

The study sample is composed by all the primary caregiver of patients with risk factors for development of PICS, which were the inclusion criteria stated as follows: An ICU length of stay of more than seven days and at least one of the following: more than three days of mechanical ventilation, presence of delirium or shock during admission. Delirium was defined by a positive result in the CAM-ICU scale and shock as the need for vasoactive therapy.

During admission to ICU the following patient variables were recorded: demographics (age, sex, weight and height, BMI, work activity), type of admission (medical or surgical), diagnosis of COVID, APACHE on admission, development of shock in ICU, days of MV, days of deep sedation, presence of delirium, presence of polyneuropathy on discharge from ICU (physical MRC) and length of stay in ICU. After discharge from ICU we recorded the destination (ward/ long-term facility) and days on hospital ward after ICU.

Exclusion criteria for patients were as follows: Failure to meet inclusion criteria, failure to give consent to participate in the study, Neurological disease with significant impairment of cognition, limiting psychiatric diseases according to DMS-IV and neurodegenerative diseases, high degree of functional and/or cognitive dependence prior to admission to the ICU. High degree of functional dependence before ICU admission was when a Barthel Index score equivalent to severe dependence. High degree of cognitive dependence was equivalent to a Pfeiffer score of moderate and severe cognitive impairment. In those patients with inability to communicate, the IQCODE scale was used. The exclusion criteria for the primary caregiver were: lack of consent to participate in the study or failure to attend the follow-up visit.

The protocol for follow-up includes an assessment 3 months after discharge from the ICU in consultation. Patients were weighed and measured and asked about the presence or absence of traumatic memories of the ICU. We also recorded if they were taking sedatives or psychoactive drugs and if they had returned to their previous work. Regarding the family we recorded variables related to demographics (sex, age), relationship to the patient (Spouse, others), employment status during and after hospital stay and if they need extra help for care their family at home. We interviewed them about several items related the ICU policy on visits, possibility of communication with patient if there were no visits and type of information (face-to-face or by telephone).

The scales used in the patients were Barthel, SF-12 (physical-mental), HADS, Pfeiffer, IES-6 and in the relatives the Apgar and Zarit. The Barthel index measures the person's ability to perform ten basic activities of daily living. The SF-12 scale assesses the degree of wellbeing and ability to function both physically and mentally. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) assesses emotional distress in patients with various chronic conditions, assessing cognitive and behavioral symptoms of anxiety and depression. The Pfeiffer scale detects the existence and degree of cognitive impairment through 10 short questions. The IES-6 is a 6-question test that measures the principal components of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. The Zarit Scale is a 22-question scale designed to assess caregiver burden, widely used in dependency studies (≤46 No strain, 47–56 Mild strain >56 Severe strain). The Family APGAR is a five-question questionnaire that seeks to assess the functional status of the family. These last two scales are available as supplementary material (Appendix I). The questionnaires were administered by two of the investigators, each of whom had demonstrated competence in the completion of the questionnaires after a mock interview with the principal investigator. With the results of the scales we defined the outcome variable (PICS-F or the presence of caregiver burden) with a Zarit test score > 46 points. Likewise, PICS in the patients was considered to be the appearance of alterations in any of the three domains. Impairment in physical domain was defined as deterioration in one category on the Barthel dependency scale with respect to admission to the ICU; impairment in cognitive domain a score of more than 3 points on the Pfeiffer test; and impairment in mental health domain a score of more than 11 on the HADS test and/or 1.75 on the IES-6 score for post-traumatic stress. Given that the scales used for the assessment of PICS at the time of the study were not standardized, we chose to use these scales because of their practicality, readability, and even the possibility of conducting them by telephone in the event of not attending to the follow-up consultation in the context of the COVID pandemic. In addition, both Barthel Scale and Pfeiffer are commonly used in the assessment at admission and discharge of ICU and the hospital, which allows us to compare the patient’s previous status with their status at the moment of follow-up.

Statistical analysis: As this was a descriptive study and with the aim of generating working hypotheses, the sample size is that of the number of patients included. The results are expressed according to the type of variable. Continuous variables are expressed as means, medians, minimum, maximum, standard deviation and interquartile range. Categorical variables were expressed as absolute values and percentages. Univariate analysis was performed using binary logistic regression and odds ratio (OR) estimation. Differences with a p<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data were anonymised for analysis. R software version 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing Platform, Vienna, Austria) r-commander 2.6−2 package was used.

Ethical considerations: The project was approved by the center’s Research Ethics Committee and consent to participate was requested from patients and relatives.

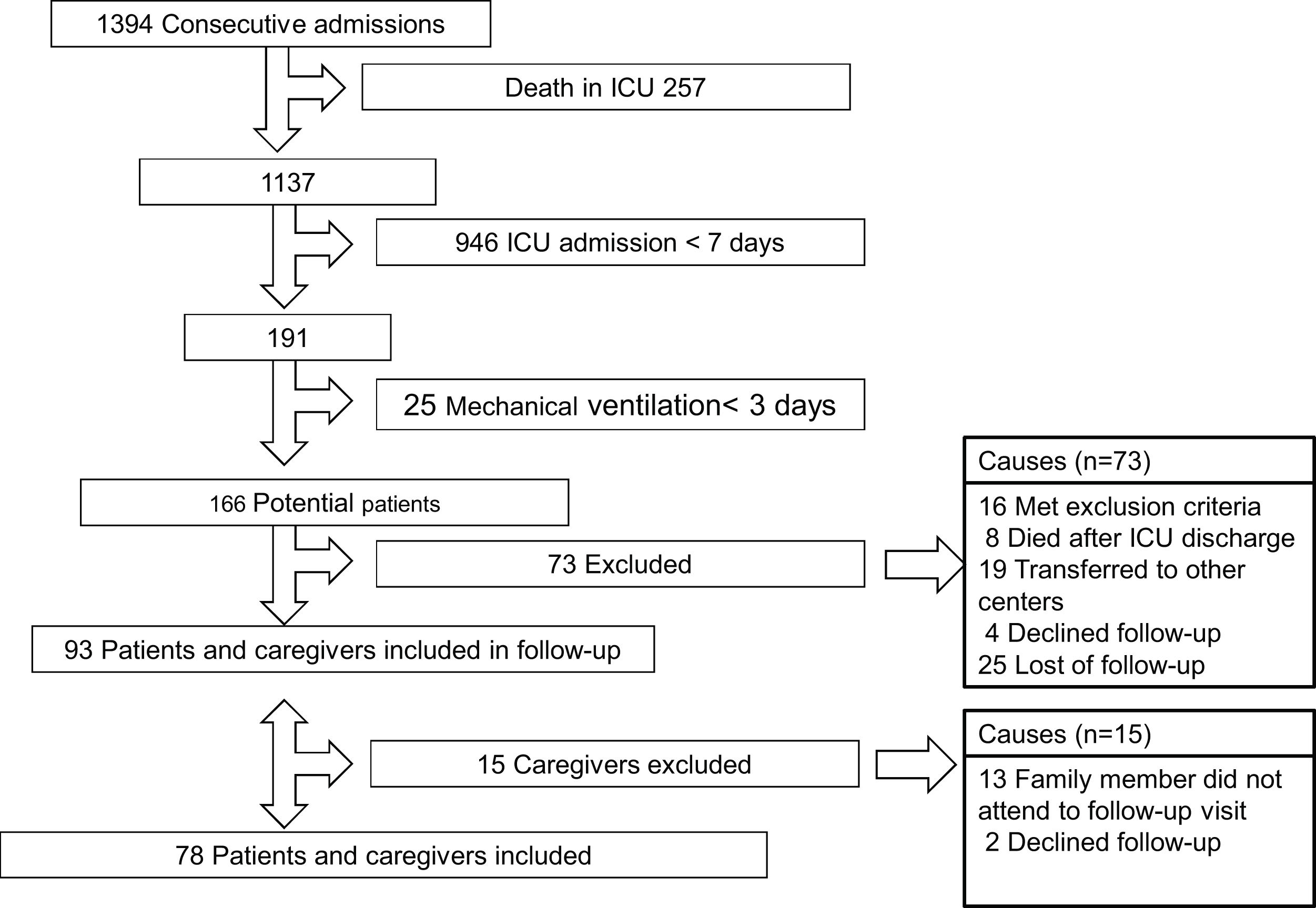

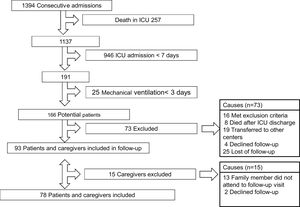

ResultsA total of 93 patients and caregivers were included in the follow up. 15 relatives did not complete the follow-up questionnaires and have been excluded from the study. The flow chart of the study is shown in Fig. 1. The incidence of PICS-F defined by the presence of primary caregiver burden in our cohort of patients is 34.6% (n=27), with a 95% CI of 25.0−45.7.

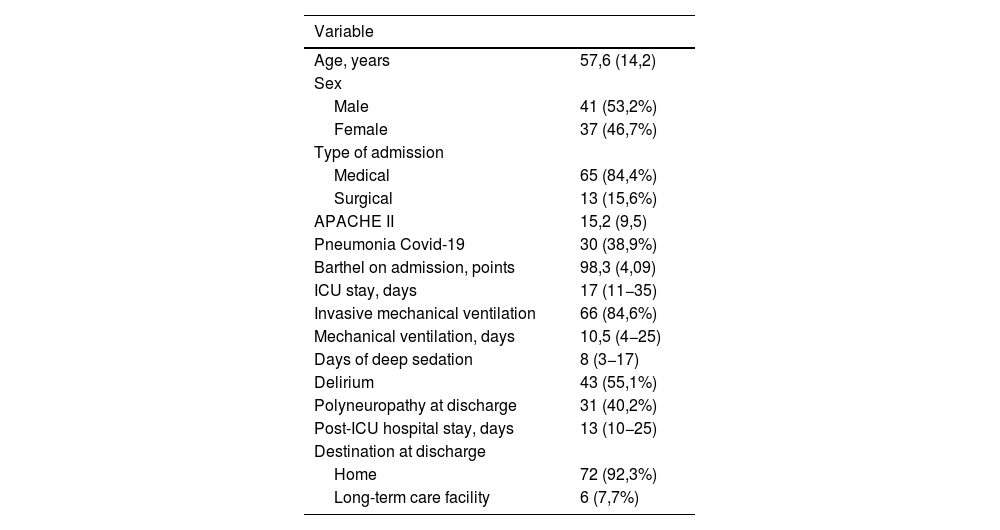

The final study group included 78 patients and caregivers. The mean age of the patients was 57.6 (14.2) years, 53.2% were male. The reason for ICU admission was medical pathology in 84.4% of cases. The mean APACHE II on admission was 15.2 (9.5). A total of 38.9% had COVID19 pneumonia on admission to ICU. The median length ICU stay was 17 (11−35) days with a median of 10.54–25 days of mechanical ventilation and 83–17 days of deep sedation. Delirium was present in 55.1% of the patients and 40.2% had critically ill polyneuropathy at ICU discharge. The mean hospital stay after ICU was 135–25 days and 92.3% of the patients were discharged home (Table 1).

Characteristics of patients admitted to the ICU.

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 57,6 (14,2) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 41 (53,2%) |

| Female | 37 (46,7%) |

| Type of admission | |

| Medical | 65 (84,4%) |

| Surgical | 13 (15,6%) |

| APACHE II | 15,2 (9,5) |

| Pneumonia Covid-19 | 30 (38,9%) |

| Barthel on admission, points | 98,3 (4,09) |

| ICU stay, days | 17 (11−35) |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 66 (84,6%) |

| Mechanical ventilation, days | 10,5 (4−25) |

| Days of deep sedation | 8 (3−17) |

| Delirium | 43 (55,1%) |

| Polyneuropathy at discharge | 31 (40,2%) |

| Post-ICU hospital stay, days | 13 (10−25) |

| Destination at discharge | |

| Home | 72 (92,3%) |

| Long-term care facility | 6 (7,7%) |

Data are expressed as n (%) or mean (SD) or median (IQR), as appropriate.

SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; MV, mechanical ventilation.

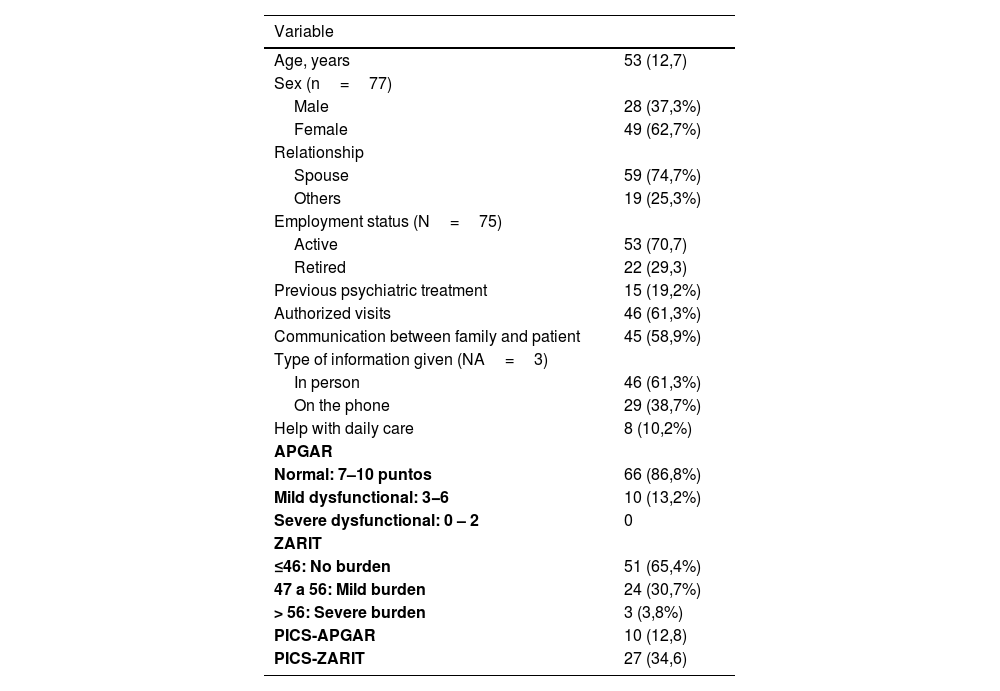

The characteristics of caregivers and family members are shown in Table 2. The mean age of this group was 53 (12.7) years, 62.7% were women, and 74.7% of the primary caregivers were the patient's spouses. In 70.7% of the cases were in active employment. Visits to the ICU were authorized in 61.3% of the cases evaluated, and communication between patient and family was allowed in 58.9% of the cases. The information given to the family by the medical team was face-to-face in 61.3% of the cases. The APGAR scale was normal in 86.8% of the cases and, as for the ZARIT scale, 30.7% of the cases presented mild burden and severe burden in 3.8%.

Characteristics of caregivers/family members.

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 53 (12,7) |

| Sex (n=77) | |

| Male | 28 (37,3%) |

| Female | 49 (62,7%) |

| Relationship | |

| Spouse | 59 (74,7%) |

| Others | 19 (25,3%) |

| Employment status (N=75) | |

| Active | 53 (70,7) |

| Retired | 22 (29,3) |

| Previous psychiatric treatment | 15 (19,2%) |

| Authorized visits | 46 (61,3%) |

| Communication between family and patient | 45 (58,9%) |

| Type of information given (NA=3) | |

| In person | 46 (61,3%) |

| On the phone | 29 (38,7%) |

| Help with daily care | 8 (10,2%) |

| APGAR | |

| Normal: 7–10 puntos | 66 (86,8%) |

| Mild dysfunctional: 3−6 | 10 (13,2%) |

| Severe dysfunctional: 0 – 2 | 0 |

| ZARIT | |

| ≤46: No burden | 51 (65,4%) |

| 47 a 56: Mild burden | 24 (30,7%) |

| > 56: Severe burden | 3 (3,8%) |

| PICS-APGAR | 10 (12,8) |

| PICS-ZARIT | 27 (34,6) |

Data are expressed as n (%) or mean (SD), as appropriate.

SD, standard deviation; ZARIT, Zarit Burden Interview; APGAR, Dimension of family functionality Score; PICS, Post-intensive care syndrome.

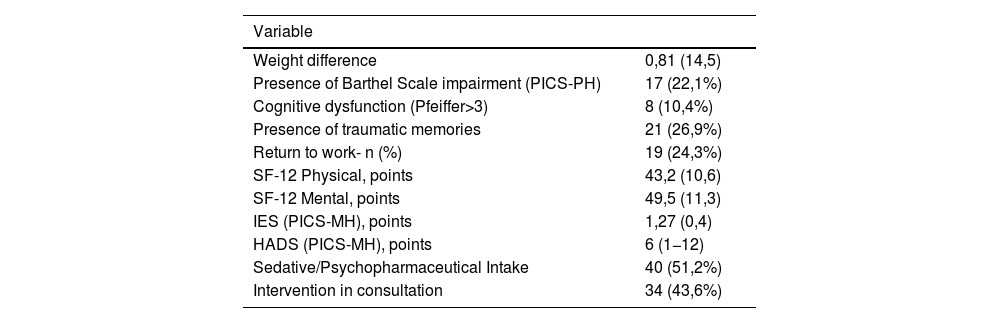

Regarding the patient's outcomes after ICU admission at 3 months follow-up (Table 3), 22.1% had physical deterioration with worsening on the Barthel scale and only 24.3% of the patients had returned to work. As for the perception of quality of life in the follow-up consultation, the mean score of the physical SF12 was 43.2 (10.6) and the mental SF12 was 49.5 (11.3), both lower than reference population value. Cognitive impairment assessed by the Pfeiffer scale was found in 10.4%. Traumatic memories of the ICU were present in 26.9% of the patients, requiring anxiolytic or antidepressant treatment in 51.2% of the cases.

Evaluation of patients at follow-up consultation (3 months).

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Weight difference | 0,81 (14,5) |

| Presence of Barthel Scale impairment (PICS-PH) | 17 (22,1%) |

| Cognitive dysfunction (Pfeiffer>3) | 8 (10,4%) |

| Presence of traumatic memories | 21 (26,9%) |

| Return to work- n (%) | 19 (24,3%) |

| SF-12 Physical, points | 43,2 (10,6) |

| SF-12 Mental, points | 49,5 (11,3) |

| IES (PICS-MH), points | 1,27 (0,4) |

| HADS (PICS-MH), points | 6 (1−12) |

| Sedative/Psychopharmaceutical Intake | 40 (51,2%) |

| Intervention in consultation | 34 (43,6%) |

Data are expressed as n (%) or mean (SD) or median (IQR), as appropriate.

SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; SF-12, Physical and Mental Health Summary scale; IES, Impact of Event Scale; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PICS-PH, Post-intensive care physical health syndrome; PICS-MH, Post-intensive care mental health syndrome.

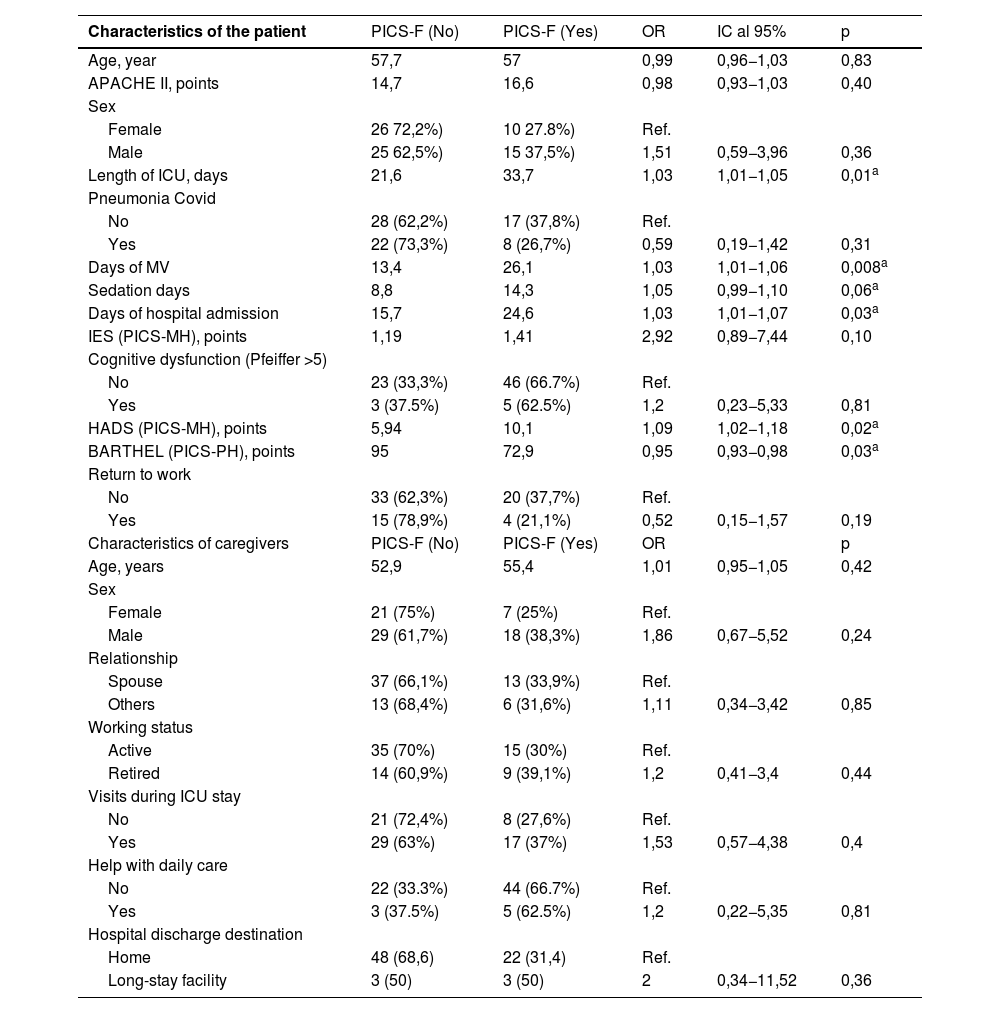

The univariate analysis of the caregivers according to whether or not they developed PICS-F is reflected in Table 4. The patient variables related to the presence of PICS-F in the primary caregiver were, in ICU: length of ICU in days OR 1.03 (p=0.01), days of mechanical ventilation OR 1.03 (p=0.008), Days of hospital admission OR 1.03 (p=0.03), days of deep sedation OR 1.05(p=0.06); and in the follow-up consultation: Barthel scale score OR 0.95 (p=0.02) and HADS scale score OR 1.09 (p=0.03). In our sample, none of the variables studied of the main caregiver in consultation was associated with the presence of PICS-F.

Univariate analysis of patient factors related to the development of family-PICS - defined by the Zarit score.

| Characteristics of the patient | PICS-F (No) | PICS-F (Yes) | OR | IC al 95% | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year | 57,7 | 57 | 0,99 | 0,96−1,03 | 0,83 |

| APACHE II, points | 14,7 | 16,6 | 0,98 | 0,93−1,03 | 0,40 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 26 72,2%) | 10 27.8%) | Ref. | ||

| Male | 25 62,5%) | 15 37,5%) | 1,51 | 0,59−3,96 | 0,36 |

| Length of ICU, days | 21,6 | 33,7 | 1,03 | 1,01−1,05 | 0,01a |

| Pneumonia Covid | |||||

| No | 28 (62,2%) | 17 (37,8%) | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 22 (73,3%) | 8 (26,7%) | 0,59 | 0,19−1,42 | 0,31 |

| Days of MV | 13,4 | 26,1 | 1,03 | 1,01−1,06 | 0,008a |

| Sedation days | 8,8 | 14,3 | 1,05 | 0,99−1,10 | 0,06a |

| Days of hospital admission | 15,7 | 24,6 | 1,03 | 1,01−1,07 | 0,03a |

| IES (PICS-MH), points | 1,19 | 1,41 | 2,92 | 0,89−7,44 | 0,10 |

| Cognitive dysfunction (Pfeiffer >5) | |||||

| No | 23 (33,3%) | 46 (66.7%) | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 3 (37.5%) | 5 (62.5%) | 1,2 | 0,23−5,33 | 0,81 |

| HADS (PICS-MH), points | 5,94 | 10,1 | 1,09 | 1,02−1,18 | 0,02a |

| BARTHEL (PICS-PH), points | 95 | 72,9 | 0,95 | 0,93−0,98 | 0,03a |

| Return to work | |||||

| No | 33 (62,3%) | 20 (37,7%) | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 15 (78,9%) | 4 (21,1%) | 0,52 | 0,15−1,57 | 0,19 |

| Characteristics of caregivers | PICS-F (No) | PICS-F (Yes) | OR | p | |

| Age, years | 52,9 | 55,4 | 1,01 | 0,95−1,05 | 0,42 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 21 (75%) | 7 (25%) | Ref. | ||

| Male | 29 (61,7%) | 18 (38,3%) | 1,86 | 0,67−5,52 | 0,24 |

| Relationship | |||||

| Spouse | 37 (66,1%) | 13 (33,9%) | Ref. | ||

| Others | 13 (68,4%) | 6 (31,6%) | 1,11 | 0,34−3,42 | 0,85 |

| Working status | |||||

| Active | 35 (70%) | 15 (30%) | Ref. | ||

| Retired | 14 (60,9%) | 9 (39,1%) | 1,2 | 0,41−3,4 | 0,44 |

| Visits during ICU stay | |||||

| No | 21 (72,4%) | 8 (27,6%) | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 29 (63%) | 17 (37%) | 1,53 | 0,57−4,38 | 0,4 |

| Help with daily care | |||||

| No | 22 (33.3%) | 44 (66.7%) | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 3 (37.5%) | 5 (62.5%) | 1,2 | 0,22−5,35 | 0,81 |

| Hospital discharge destination | |||||

| Home | 48 (68,6) | 22 (31,4) | Ref. | ||

| Long-stay facility | 3 (50) | 3 (50) | 2 | 0,34−11,52 | 0,36 |

Data are expressed as n (%) or mean (SD) or median (IQR), as appropriate.

SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; PICS-PH, Post-intensive Care syndrome physical health; PICS-MH, post-intensive care syndrome mental health; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ref, reference category.

The incidence of PICS-F as defined by the presence of primary caregiver burden in our cohort of patients is remarkably high. We expected it to be associated with patient-related factors, with the caregivers themselves and the policies for the care of families during their time in the ICU. However, we did not identify in our sample any family member risk factor for the development of PICS-F. What has determined caregiver burden in our study has been the presence of PICS in the patient (in the physical and mental domains) mediated by the length of mechanical ventilation, sedation and ICU/hospital admission.

PICS-F has previously been defined as the family member's response to the stress caused by the admission of a loved one to an ICU.8 There is great diversity in the literature on how to assess family member or primary caregiver burden in ICU patients.10,11 Caregiver strain assessed with the Zarit scale12 has been extensively studied in other populations like geriatric, oncology, palliative or paediatric.13,14 The Zarit scale has also been used in relatives of critically ill patients to assess PICS-F.15,16 In the systematic review carried out by Beusekom et al.,8 the prevalence ranged from 12.2%–26.2% at 3 months after discharge from the ICU. The cross-sectional study recorded a prevalence of 31.9%, these results being similar to those obtained in our study.

In our sample, caregiver burden is significantly associated with the patient's time variables (days of mechanical ventilation, sedation, ICU stay and hospital admission). These variables are strongly correlated with the presence of PICS in the physical and mental health domains in the patient 3 months after discharge from the ICU.17 The association between PICS physical and mental domain impairment and caregiver burden has also been described by other groups such as Swoboda et al.,18 Choi et al.19 and Iglesias et al.20

As for studies relating the alteration of the mental health domain of the PICS to caregiver burden, Cameron et al.21 found that caregiver emotional distress was greater when ARDS survivors reported more depressive symptoms, results that were also described by Torres et al.14 and recently by Shirasaki et al.22 All these studies are consistent with the results obtained in the present study. Other studies have explored the characteristics of family members or primary caregivers as possible predictors of PICS-F and have found that female sex,23–25 young age,21,24 a spousal relationship with the patient,20 cohabitation with the patient,23 the presence of a pre-existing mental health disorder25 appear to predispose to PICS-F. We have not identified any caregiver risk factors that are associated with the development of PICS-F. This may be due to the deselection bias introduced by the fact that we did not analyze relatives of patients who died within the first 3 months after ICU discharge and those who did not present for consultation or refused to participate in the study. On retrospectively reviewing their demographic characteristics (age, sex, family relationship) there were no significant differences. There are several potentially promising approaches or interventions for the prevention of PICS in both patients and family members that could be initiated in the ICU. These modifiable factors, such as flexible visiting hours, method of debriefing or use of ICU diaries, may result in less post-traumatic stress disorder among family members/caregivers of ICU patients.2,26

In our sample, the possibility of visits or the method of information were not significantly related to less caregiver burden at 3 months, although we cannot conclude that the absence of visits or the different formats of information, whether in person or by telephone, are not associated with the presence of post-traumatic stress disorder in the caregiver, as this variable was not assessed.

In follow-up consultation, once PICS was diagnosed in the patient or in the relative/caregiver, the necessary therapeutic interventions were carried out to guarantee the best health care, either referral to different specialists (rehabilitation, nutrition, mental health) in the case of patients and in the case of relatives, counseling and referral to the mental health unit were provided.

From the results of our study it is clear that one of the main points of preventing PICS-F is also preventing the patient’s own PICS. There is no doubt that there are elements that are not modifiable and depend on the severity of the disease and the functional reserve of the patient. However, we already know of intervention to be carried out in the ICU itself that can help reduce the physical and psychological sequelae. The former include the reduction of length of mechanical ventilation and deep sedations, as well as early mobilization.27,28 As for psychological alterations, there is less evidence, but all aspects related to the humanization of care should be investigated and adopted as a fundamental part of this type of unit.29–31

Our study has the following limitations. Given that our inclusion criteria were based on a length of stay in the ICU of more than a week, the number of patients and caregivers finally recruited was low. The causes of exclusion may also have influenced the results, as the relatives of these patients may have different characteristics to those who participated voluntarily. The visiting regime may have impacted the results. Given that the study was impacted by the COVID pandemic, the visiting regime and the possibility of providing information to family members varied with respect to the usual functioning of the unit. As a result, only 61.3% of visits were authorized and 61.3% of information was provided in person. As this was a pilot and single-centre study with a limited number of patients, it was not possible to perform a multivariate analysis. The results should be considered preliminary and should be confirmed in future studies with higher number of participants. Nevertheless, our preliminary findings may serve as a starting-point for further research.

In summary, in our study one in three family members of patients with risk factors for the development of PICS have caregiver burden at 3 months. The presence of physical deterioration, anxiety or post-traumatic stress in the patient is related to primary caregiver burden. The identification of patients with risk factors for the development of PICS during their stay in the ICU as well as the presence of PICS in the follow-up consultation should raise the alarm that the family member should also be assessed and provided with the corresponding therapeutic assistance.

Authorship and contributionAll authors have made substantial contributions in each of the following aspects:

- (1)

Conception and design of the study: Manuel Colmenero, Julia Tejero Aranguren and Raimundo Garcial del Moral.

- (2)

Acquisition of data,or analysis and interpretation of data: Manuel Colmenero, Julia Tejero Aranguren, M Eugenia Poyatos Aguilera and Raimundo Garcial del Moral.

- (3)

Drafting of the article or critical revision of the intellectual content: Julia Tejero Aranguren, Manuel Colmenero and Raimundo Garcial del Moral.

- (4)

Final approval of the version presented: Manuel Colmenero, Julia Tejero Aranguren, M Eugenia Poyatos Aguilera and Raimundo Garcial del Moral.

All authors declare that they have participated in the research work and/or preparation of the article.

FundingAll authors declare that they have not received funding for this study.

Conflict of interestsAll authors declare that they have no commercial or other conflicts of interest, that they have adhered to the ethical standards applicable to human research studies and have sought approval both from the relevant Ethics Committee and from the participants or their representatives, that this manuscript has not been published in another journal and is not under consideration by another journal, and that they have participated in the study, approved the manuscript and agree to its submission to Medicina Intensiva.