Research in the critically ill is complex by the heterogeneity of patients, the difficulties to achieve representative sample sizes and the number of variables simultaneously involved. However, the quantity and quality of records is high as well as the relevance of the variables used, such as survival. The methodological tools have evolved to offering new perspectives and analysis models that allow extracting relevant information from the data that accompanies the critically ill patient. The need for training in methodology and interpretation of results is an important challenge for the intensivists who wish to be updated on the research developments and clinical advances in Intensive Medicine.

La investigación en el enfermo crítico es compleja por la heterogeneidad de los pacientes, por las dificultades para alcanzar tamaños de muestra representativos y por la cantidad de variables que intervienen de manera simultánea. Sin embargo, se beneficia de la cantidad y calidad de registros, así como de la relevancia de las variables utilizadas, como la supervivencia. Las herramientas metodológicas han evolucionado ofreciendo nuevas perspectivas y modelos de análisis que permiten extraer información relevante de la riqueza de datos que acompaña al enfermo crítico. La necesidad de formación en metodología y en interpretación de resultados constituye un importante reto para los intensivistas que deseen estar al día en las líneas de investigación y en los nuevos avances de la Medicina Intensiva.

The series of methodology we start in Medicina Intensiva tries to bring the clinician closer to different methodological issues that we have considered relevant in the research setting of critically ill patients.

Critical disease has some special conditions when it comes to generating scientific knowledge.1 On the one hand, the amount of monitoring and the availability of tests in these patients provides a great deal of analyzable information. Also, the high impact of physiopathological aspects allows us to go deep into applied basic research. Due to the patients’ fast progression and rates of survival, variable mortality is commonly used, generating high interest and clinical relevance to clinical researches. On the other hand, the velocity of changes, complexity, and interrelation of variables and simultaneous treatments, working schedules, and difficulties trying to find homogeneous enough patients in one single center elevates the requirements of study designs, and resources needed.2

All these challenges lead to two (2) fundamental issues. On the one hand, the need to find tools for statistical analysis adjusted to data, and possible designs with critically ill patients, which is why new and diverse approaches are needed. On the other hand, it is important to improve methodological training for research purposes and also for the interpretation of results. In this series we do not wish to write a statistical treaty, but draw an interesting picture including general aspects of result interpretation as advanced topics among which we will find new strategies of analysis, or big data.

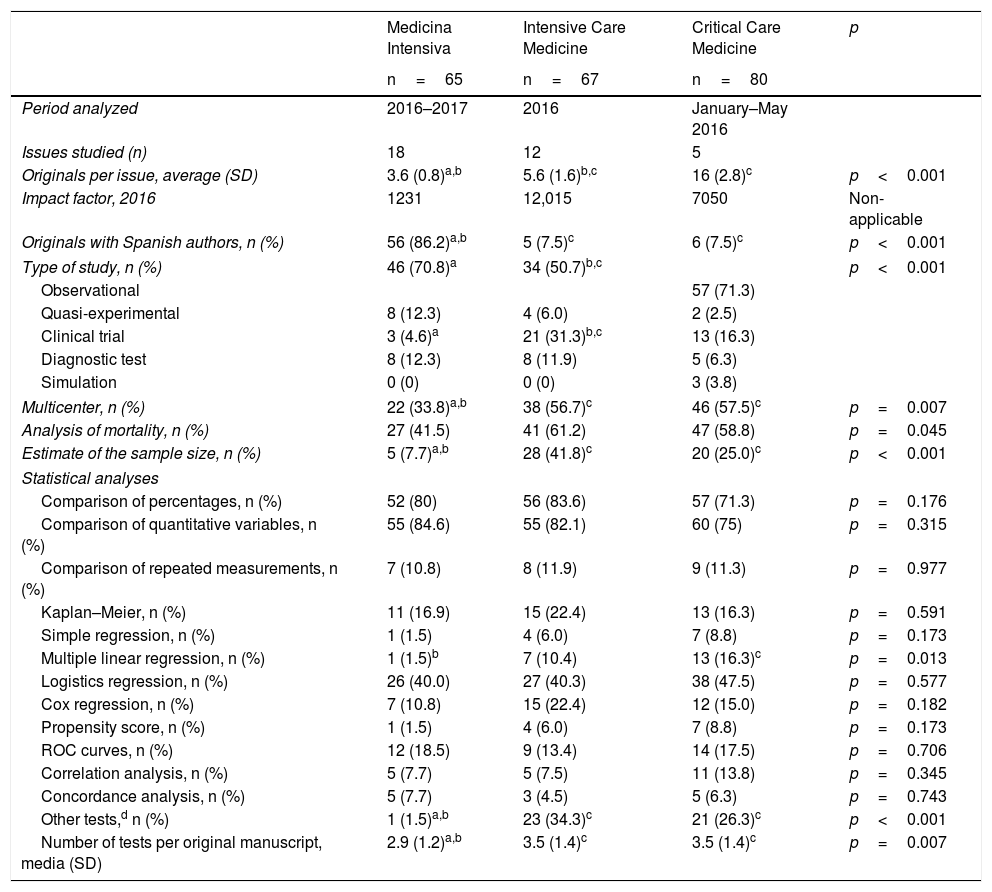

In one comparative analysis of the statistical techniques used in 3 journals dedicated to the critically ill patient (Medicina Intensiva, Intensive Care Medicine, and Critical Care Medicine), we analyzed the methodological procedures used in one recent sample of the original manuscripts published during 2016 and 2017 (Table 1). Other than the differences seen in the number of original manuscripts published per issue, and in the presence of Spanish authors in the three (3) journals, we found significant differences in the type of studies conducted and in the complexity of the methodology used. Although the three journals mostly use observational studies, compared to the other two journals, Intensive Care Medicine includes a higher percentage of clinical trials, being such trials rare in Medicina Intensiva (4.6%). In Medicina Intensiva, the percentage of multicenter studies is lower than in the other two journals, and there are not too many estimates of the size of the sample either, probably due to the fact that fewer clinical trials are published.

Comparative analysis of the statistical methodology used in the original manuscripts published in three (3) journals within the intensive care setting.

| Medicina Intensiva | Intensive Care Medicine | Critical Care Medicine | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=65 | n=67 | n=80 | ||

| Period analyzed | 2016–2017 | 2016 | January–May 2016 | |

| Issues studied (n) | 18 | 12 | 5 | |

| Originals per issue, average (SD) | 3.6 (0.8)a,b | 5.6 (1.6)b,c | 16 (2.8)c | p<0.001 |

| Impact factor, 2016 | 1231 | 12,015 | 7050 | Non-applicable |

| Originals with Spanish authors, n (%) | 56 (86.2)a,b | 5 (7.5)c | 6 (7.5)c | p<0.001 |

| Type of study, n (%) | 46 (70.8)a | 34 (50.7)b,c | p<0.001 | |

| Observational | 57 (71.3) | |||

| Quasi-experimental | 8 (12.3) | 4 (6.0) | 2 (2.5) | |

| Clinical trial | 3 (4.6)a | 21 (31.3)b,c | 13 (16.3) | |

| Diagnostic test | 8 (12.3) | 8 (11.9) | 5 (6.3) | |

| Simulation | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.8) | |

| Multicenter, n (%) | 22 (33.8)a,b | 38 (56.7)c | 46 (57.5)c | p=0.007 |

| Analysis of mortality, n (%) | 27 (41.5) | 41 (61.2) | 47 (58.8) | p=0.045 |

| Estimate of the sample size, n (%) | 5 (7.7)a,b | 28 (41.8)c | 20 (25.0)c | p<0.001 |

| Statistical analyses | ||||

| Comparison of percentages, n (%) | 52 (80) | 56 (83.6) | 57 (71.3) | p=0.176 |

| Comparison of quantitative variables, n (%) | 55 (84.6) | 55 (82.1) | 60 (75) | p=0.315 |

| Comparison of repeated measurements, n (%) | 7 (10.8) | 8 (11.9) | 9 (11.3) | p=0.977 |

| Kaplan–Meier, n (%) | 11 (16.9) | 15 (22.4) | 13 (16.3) | p=0.591 |

| Simple regression, n (%) | 1 (1.5) | 4 (6.0) | 7 (8.8) | p=0.173 |

| Multiple linear regression, n (%) | 1 (1.5)b | 7 (10.4) | 13 (16.3)c | p=0.013 |

| Logistics regression, n (%) | 26 (40.0) | 27 (40.3) | 38 (47.5) | p=0.577 |

| Cox regression, n (%) | 7 (10.8) | 15 (22.4) | 12 (15.0) | p=0.182 |

| Propensity score, n (%) | 1 (1.5) | 4 (6.0) | 7 (8.8) | p=0.173 |

| ROC curves, n (%) | 12 (18.5) | 9 (13.4) | 14 (17.5) | p=0.706 |

| Correlation analysis, n (%) | 5 (7.7) | 5 (7.5) | 11 (13.8) | p=0.345 |

| Concordance analysis, n (%) | 5 (7.7) | 3 (4.5) | 5 (6.3) | p=0.743 |

| Other tests,d n (%) | 1 (1.5)a,b | 23 (34.3)c | 21 (26.3)c | p<0.001 |

| Number of tests per original manuscript, media (SD) | 2.9 (1.2)a,b | 3.5 (1.4)c | 3.5 (1.4)c | p=0.007 |

SD: standard deviation. ROC: receiver operating characteristics.

Methods used: Bayesian analysis (1), qualitative analysis (1), clusters analysis (2), analysis of the main components (2), multiple concordance analysis (1), mediation analysis (1), factorial analysis (1), fractal analysis (1), decision tree (1), generalized estimating equations (2), phi statistics (1), gradient boosted machine (1), G-Study (1), Inverse probability treatment weighting (IPWT) (2), jointpoint regression (1), K-nearest neighbors (1), Locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOWESS) (2), Modified early warning systems (MEWS) (1), negative binomial model (1), generalized linear model (12), generalized mixed linear model (2), structural marginal model (4), simulation models (2), Montecarlo (2), network maps (1), neural network (1), Cochran-Armitage trend test (2), random forest (1), binomial regression (1), Poisson regression (5), competitive risks (2), temporal series (4), support vector machine (1) and Cuzick's test (1).

On the statistical analyses, the number of tests used is much lower in Medicina Intensiva than it is in the other two journals, although in the most common methods we did not find any significant differences, except in the multiple linear regression analysis. Where we did find a clear difference is in the use of more advanced statistical methods, almost inexistent in the original manuscripts from Medicina Intensiva, but present in one third of the originals from Intensive Care Medicine and Critical Care Medicine. The greater use of advanced tests has become a common practice and is a clear improvement compared to similar assessments made in high-impact factor journals some 20 years ago.3

In sum, we found a significant difference in the level of design complexity and statistical analysis in the manuscripts submitted to Medicina Intensiva compared to the other two (2) journals.

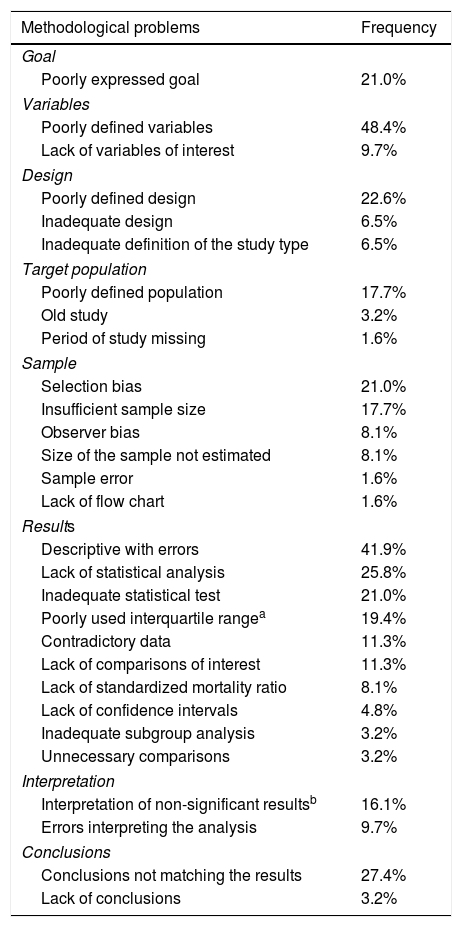

On the other hand, in one review conducted on a sample of 62 original manuscripts submitted for publication to Medicina Intensiva from 2016 through 2017, we found a series of methodological problems that are shown in Table 2 being the most common ones, per frequency of appearance, the inadequate definition of variables, the mistakes made in the description of results, the fact that conclusions did not match the results, the lack of statistical analysis (multivariate models, above all), the existence of not very clear designs, the inadequate presentation of the goal, selection biases, and the use of inadequate statistical tests for analysis. These problems have also been found in other publications4 and, in this sense, the use of reviewers trained in statistics during the review process has proven a useful tool to improve the quality of the articles published5 and implies some sort of ethical commitment.6

Main methodological problems found in the first review of original manuscripts submitted to Medicina Intensiva from 2016 through 2017.

| Methodological problems | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Goal | |

| Poorly expressed goal | 21.0% |

| Variables | |

| Poorly defined variables | 48.4% |

| Lack of variables of interest | 9.7% |

| Design | |

| Poorly defined design | 22.6% |

| Inadequate design | 6.5% |

| Inadequate definition of the study type | 6.5% |

| Target population | |

| Poorly defined population | 17.7% |

| Old study | 3.2% |

| Period of study missing | 1.6% |

| Sample | |

| Selection bias | 21.0% |

| Insufficient sample size | 17.7% |

| Observer bias | 8.1% |

| Size of the sample not estimated | 8.1% |

| Sample error | 1.6% |

| Lack of flow chart | 1.6% |

| Results | |

| Descriptive with errors | 41.9% |

| Lack of statistical analysis | 25.8% |

| Inadequate statistical test | 21.0% |

| Poorly used interquartile rangea | 19.4% |

| Contradictory data | 11.3% |

| Lack of comparisons of interest | 11.3% |

| Lack of standardized mortality ratio | 8.1% |

| Lack of confidence intervals | 4.8% |

| Inadequate subgroup analysis | 3.2% |

| Unnecessary comparisons | 3.2% |

| Interpretation | |

| Interpretation of non-significant resultsb | 16.1% |

| Errors interpreting the analysis | 9.7% |

| Conclusions | |

| Conclusions not matching the results | 27.4% |

| Lack of conclusions | 3.2% |

Number of originals analyzed=62.

It is, therefore, evident that there is margin for improvement in methodological design, and in the analysis and interpretation of results in all research studies submitted to our journal. The Editorial Committee of Medicina Intensiva, directed by Dr. Garnacho Montero, understands that this journal needs to draw and promote studies of high methodological quality that, in time, will improve the impact factor and promote the submission of new quality studies.7 Within this virtuous circle setting, this series is born in an attempt to improve the quality of our investigations.

This series begins with a general reflection on the particularities that affect the studies of critically ill patients, and we will be discussing the difficulties, different approaches, and new strategies defined to make scientific knowledge move forward. Also, we will be analyzing the interpretation of statistical results in its most basic and advanced aspects, trying to facilitate an adequate understanding of the terminology used in the most common scientific literature. This paper is a review of common methodological errors made in clinical research, some of which can be more or less innocent, but all will undoubtedly help the reader keep a critical view of the information presented here. We will also be reviewing a fundamental aspect known as the bioethics of clinical research–very important for the editorial team,7 a historical summary will be presented here, followed by an analysis of the different ethical requirements that are mandatory in the clinical research of critically ill patients.

When we open up the arsenal of statistical tools available, three (3) reviews can be conducted: one review on the techniques used to determine the causality of observational studies with an emphasis on propensity score analysis; a second review on new techniques of alternative analysis such as hybrid studies, nested case–control studies, recursive partitions, or competitive events, one article discussing the development of systematic reviews, and meta-analyses as sources of knowledge. Lastly, we have addressed a popular issue these days by including an update on big data–the tool that will probably revolutionize the way we understand the clinical information available, and, ultimately, condition the way we make decisions.

We hope that the readers of Medicina Intensiva find this series of methodology interesting, and a source of inspiration to keep moving forward in the fascinating world of clinical research in the critically ill patient.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interests associated with this article whatsoever.

Please cite this article as: García Garmendia JL. Actualización en metodología en Medicina Intensiva. Med Intensiva. 2018;42:180–183.