The humanization of care emerges as a response to something that seems indisputable: the scientific and technological developments in Intensive Care Units. Such development has improved the care of the critically ill patient in quantitative terms, but has perhaps caused the emotional needs of patients, families and professionals to be regarded as secondary concerns. The humanization of healthcare should be discussed without confusing or discussing the humanity displayed by professionals. In this paper we review and describe the different strategic lines proposed in order to secure humanized care, and adopt a critical approach to their adaptation and current status in the field of pediatric critical care.

La corriente humanizadora surge como respuesta a un hecho que parece indiscutible: el desarrollo científico y tecnológico de las Unidades de Cuidados Intensivos. Este ha mejorado el cuidado del paciente crítico en términos cuantitativos y ha relegado, quizá, las necesidades humanas y emocionales de pacientes, familias y profesionales a un segundo plano. La humanización debe ser objeto de debate, sin que esto se confunda con poner en duda la humanidad desplegada por los profesionales. Se analizan y describen en este trabajo las líneas estratégicas sobre las que pivota el cuidado humanizado del paciente crítico, adaptándolas al ámbito pediátrico.

Over the last few years, humanization seems to be a common word in the healthcare setting.1 Whether before or after a therapeutic attitude, humanization is the sweetener that turns the healthcare activity into something different that is still not very well defined.2 If we take a look at the existing medical literature, the evidence that justifies its clinical utility is still scarce and, above all, based on the perceived benefit that this attitude brings to the care of both patients and healthcare providers.

While writing this manuscript, a reference search browsed on PubMed® without strict criteria showed that the humanization of healthcare is at the foundation of 224 papers of which 69 have been published during the last 5 years, and barely 2 are clinical or comparison trials. If we browse this same search on Google®, the number of results obtained is 254,000 that corresponds not only to scientific papers, but also to unfounded studies that add value to this attitude beyond objectivity.3

This humanization trend comes in response to a fact that seems undisputed: the scientific and technological development of Intensive Care Units (ICU) has improved the management of critically ill patients in quantitative terms but also pushed the human and emotional needs of patients, families and healthcare providers aside.3,4 The verb to humanize is controversial and maybe it is with a certain critical perspective that we may find its defense.5 We should not trivialize it or open the doors wide open to interventions that allegedly humanize as an essential part of their sense and utility (an example of this are the wrongly named alternative therapies).6 The debate of humanization should be on the table, but this debate should not put the humanity shown by healthcare providers into question. Thus, we are confronted with the need to know where we stand today and where we’re heading to with our clinical practice.5,7–9

Humanization of pediatric intensive careIn the pediatric setting, the attitude shown toward the patient would be called, in the adult setting, humanized.7 The presence of family members, their participation in the care provided, the nearness to the patient, or the interpretation of signs and symptoms beyond pain, fever, or clinical complications are common practices in the neonatal or pediatric intensivist setting. To some extent the new road faced by the adult population is already happening in our setting.10

In an attempt to structure this point of view, several scientific societies have established the development of a dynamic flight plan that should allow the development of humanization in the context of critically ill patients. Thus, based on the Humanization Plan of Intensive Care Units of the Community of Madrid published back in 2016, our paper outlines and describes the strategic lines upon which the implementation and development of human care in the management of critically ill patients should be built.1 This manuscript should be taken as no protocol or flight plan and all these strategic lines should be summarized and adapted to the pediatric setting.

Open door intensive care unitAn open door intensive care unit (ICU) can be defined as a unit aimed at reducing or eliminating any limitations imposed in the temporal and physical dimensions as well as in the relationships for which there is no justification whatsoever.9 In general, an open door ICU makes reference to the set of rules and regulations established for the good functioning of the ICUs aimed at promoting communication between patients and their families, and between families and healthcare providers. It includes interventions aimed at liberalizing time, the number of visitors, proximity (physical contact, close waiting rooms) and communication.11

Historically in the model of healthcare provided to adult critically ill patients, the policy of visits from family members has been based on a restrictive model.12 It was thought that this pattern favored the healthcare provided to patients in their sickness and also facilitated the job done by the healthcare providers. Thus, the study conducted by Escudero et al. back in 2015 on visit hours and level of comfort in Spanish adult ICUs described that 3.8% of all ICUs allowed visits throughout the day and 9.8% only during day time. The remaining ICUs restricted visit hours to two times a day and only to a limited number of visits.13

In the pediatric setting, visit hours are usually less restricted with a few exceptions like the ones described by Giannini et al. in Italy.14 Children are dependent by nature until they become of age or reach psychological maturity. This makes us have to keep some kind of differential attitude. Parents or caregivers are usually always present in the ICU for two reasons: they are essential for the patients and necessary for the healthcare providers. Parents or caregivers know what's wrong with their child and, at times, they are the catalyst for what the child actually needs. Also, they can interpret certain signs and symptoms which, in turn, facilitates diagnosis and the prescription of therapy.7

Yet despite all this, the presence of caregivers is controversial. When in the presence of serious conditions, when invasive procedures need to be conducted, when the child needs care, or when dealing with life or death situations like cardiac arrests the presence of caregivers is still controversial.15 In most cases, the studies conducted on this issue are based on questionnaires delivered to healthcare providers that do not take into consideration the wishes from the patient or the family (Table 1) so there is actually evidence both for and against the presence of the patient's relatives. On this controversial issue, we should mention here the study conducted by Soleimanpour et al. in which, surprisingly for the authors as they say in their conclusions, the staff from two Swiss ICUs opposed this attitude claiming clinical, spiritual, or labor reasons.16

Reasons and arguments for an open door intensive care unit.

| Visitors do no increase the risk of infectionContinuous communication favors the process of informationThe families can help in the recovery of the patient and be an essential part of the ICU teamThe child has the right to be accompanied by his parents at all time (European Charter for Children in Hospital, 1986)The presence of parents and families reduces the child's stress, fear, and anxiety as well as his needs for sedation and analgesia, favors synchrony with the respirator, and reduces cardiovascular stress and shortens the stay at the pediatric ICUParental participation in the child's care minimizes the parent's anxiety and fear which, in turn, helps in the child's healing processParental participation in the child's care can minimize nursing times tooThe family has the right and responsibility to participate in the end-of-life processIt is good for the ICU to assess the work being done and improve human relations |

Source: Taken from the Humanization Plan of Intensive Care Units of the Community of Madrid.16

Given the discreet scientific evidence and in an attempt to do whatever the patient actually needs and not what we think he may need, we should promote further research on this issue. Awareness and adaptation to a new paradigm when it comes to accompanying patients seems reasonable, but it should always be based on a critical gradual thinking of the criteria developing such new paradigm.

CommunicationCommunication is a key element of human relations and also for those who work on a daily basis in intensive care units. To them, it is essential to be able to inform, ask, and display attitudes or decisions made. It not only involves an information exchange, but also improvement of the parties involved in this communicative process. In the context of healthcare, communication with the patient and his family is a concept we don’t pay too much mind to. Generally speaking, we rather care for clinical communication among different healthcare providers. We seem to be more interesting in acquiring skills to know how to give bad news or manage stressful situations, rather than improving how to communicate better among ourselves.17

It is true that, at the ICU setting, healthcare-focused information is one of the main concerns for patients and families alike and the lack of information or the inability to provide information is at the heart of several claims. In this sense, the pediatric patient is unique because, even though he's got the right to be informed, on many occasions, and given his age, these rights are transferred to his family. Providing information in situations of great emotional load requires communication skills and specific training that most healthcare providers just don’t have.

We should not forget here that, at the ICU setting, team work among the different healthcare providers is essential and requires, among other things, clear, precise, complete and timely communication. Therefore, whenever information is being provided, not only data but also responsibility (such as changing shifts or calls or referring patients to other units or services, etc.), we are witnessing critical moments.11 In turn, conflicts among the staff at the ICU are a common thing and, most of the time, they have to do with ineffective communication patterns. These conflicts arte a threat to the very idea of what a team should be and have a direct influence on the well-being of patients and their families, cause fatigue, discourage among the staff, and elevate the cost of healthcare.

Although there are a few shared models, no specific policies on how to proceed with the provision of information at the ICU setting have been enacted. In Spain these policies are extremely rigid: 80% of adult ICUs provide information just once a day and only 5% of the ICUs provide information as requested by the families.13 The information provided by doctor and nurse together is rare too. In general, the role played by the nursing staff when providing information is insufficient and has not been well-established, yet despite the essential role nurses play in the care of critically ill patients and their families.

Finally, among all the events that take place at an ICU, one of the most stressful of all according to the patients is the inability to speak that eventually leads to panic, insecurity, sleep disorders, and high levels of stress. Most of the patients who die at the ICU cannot communicate their needs and wishes at the end of their lives or give messages to their loved ones. Therefore, it is essential that we improve any attempts of communication with patients with limited communication skills by promoting the use of augmented and alternative communication systems. At the pediatric ICU, the presence of parents and the regular caregivers is considered helpful, yet it has not been fully explored. Actually according to a study conducted by Needle et al. back in 2009, it seems that in one third of the cases, doctors and those in charge of the patient do not perceive the parents’ anxiety and preoccupation, and don’t even provide appropriate information.18 Thus, it is reasonable to believe that their presence is necessary, but this is something that should be explored and studied so we can finally turn this ideal into a true fact with proven sense and utility.10,14

Well-being of patients and healthcare providersThe patient's well-being should be a primary goal same way as his healing and even more important when the latter is not possible. The patient's disease generates discomfort and pain that grows with the interventions performed on him.19 Added to this physical pain, we cannot overlook or ignore the psychological suffering conveyed. Any disease causes uncertainty, pain, anguish…that can bring more suffering that physical pain per se.20 It is obvious that this perspective makes us wonder what is being done and what should be changed.

In the pediatric population, the neonatal stage has always been seen as that stage where these facts are usually underestimated. Studies like the one conducted by Anand et al. back in 2017 show that up to one third of all newborn babies hospitalized in ICUs are not assessed daily of their pain.21 This is worse if we think of the baby's emotional suffering as an added variable.

In the pediatric critically ill patient these aspects should be part of the healthcare provided by giving real importance derived from an adequate rigorous management without implementing far-fetched solutions (should intensivists learn the skills of a clown?).2 Taking care of the routines, the sleep-wakefulness cycle, thirst, cold, family relations and the child's own autonomy should be gradually integrated in his daily activities. Assessing and monitoring pain, finding the right dynamic sedation for the patient, and preventing and managing acute delirium are essential if we wish to improve the patients’ well-being. When it comes to delirium, several research lines are being considered now that claim that this problem is being underestimated while they emphasize its assessment, anticipation, and management. Recent studies like the international study conducted by Traube et al. show a new and interesting horizon on this issue.22

We should also mention here that the labor conditions at an ICU do not contribute to the patient or healthcare provider's well-being. Humanizing is taking care of the caregivers too. Alleviating this psychological discomfort probably requires from healthcare and political institutions a change of paradigm in the way they approach working in these units by providing physical and emotional care for everyone working at an ICU. Working hours pass different from one person to the next, that is true, but acting together based on the actual needs of the staff will improve everyone's well-being at the ICU setting. This is a complex issue though because we’d not only need to change the how but also the how much.23

Presence and participation of the family in the healthcare being providedAs we have already said, family participation in the healthcare process is unusual in neonatal and pediatric ICUs. The guidelines established by the American Society of Pediatrics recommend adapting healthcare to every child and his family individually and being flexible, honest, and impartial both with the procedures performed and with the information provided. Collaboration and support should facilitate the use of the strengths derived from the child's daily care.24 This issue is even more conflicting in adult ICUs where the physical needs and the complications associated with the complexity of management and the way adults move in the ICUs setting are an actual obstacle.25

Based on studies conducted among families of adult patients admitted to ICUs, they have a clear desire to participate in the healthcare process.9 That is why if the clinical conditions are right, families who are willing to do so, should collaborate in this healthcare process but only after being trained and always under the direct supervision of the healthcare providers. Giving the families the opportunity to help in the recovery of the patient can have positive effects on him, on the relatives and on the healthcare providers since they minimize emotional stress and contribute to the nearness and communication of all the parties involved.24 Also, family participation in the daily informative rounds favors the questions being asked and includes the relatives involved in the decision-making process.26

There is greater controversy when it comes to procedures. In general, adult ICU intensivists don’t think that the family should be present while they are implementing their procedures: they talk about the psychological trauma and anxiety that may generate in the family, interfering when doing the procedures, distractions, and the possible impact this may have on the healthcare team as a whole.9,13 This is a turning point due to the different studies conducted so far on these issues. Even though the studies are not conclusive, the presence of the family has not been associated with any negative consequences, but it does cause certain attitudinal changes such as greater preoccupation from the healthcare providers on issues such as privacy, dignity, and pain management while procedures are being witnessed. Also, there is greater family satisfaction, and a better acceptance of the situation which in turn should help during the process of mourning. With respect to the pediatric patient, family presence is also considered beneficial for the patient. In many cases, this statement is empirical and requires the adequate training of all healthcare providers involved. This controversy is still under discussion today from the bioethical point of view. The ‘ayes’ are beating the ‘nays’ but there are still issues under discussion here. That is why the study conducted by Vincent et al. is really interesting. They establish differences with the population of adult patients and wonder what could be done when dealing with cardiopulmonary resuscitation maneuvers. The authors list three (3) facts that should be taken into consideration in the pediatric patient: the child does not usually speak up about his family being present because he doesn’t really know how to do this. There are no studies today that provide actual evidence on the real benefit of this, and the mid- and long-term consequences of this attitude have not been fully explored yet.27

Taking care of healthcare providersIn general, healthcare providers do their job from a vocational perspective. They give themselves to their job on a daily basis because taking care of patients requires commitment and involvement. Also, this gives them enormous personal satisfaction when expectations are met, when the job done is a quality job, when patients get better, when suffering is suppressed or even when they get the credit they deserve. However, when things don’t go as expected, the emotional wear and tear is tremendous. Also, when this happens together with a lack of personal healthcare and well-being, then we may encounter the so-called burnout syndrome.

There is general consensus that this is a response to chronic labor stress with negative connotations since it leads to negative consequences for the individual and for the organization he works at. One of the most widely used conceptualizations of this has been Maslach and Jackson's who characterize the emotional tear syndrome or loss of emotional resources to cope with one's job, the depersonalization disorder or development of negative attitudes, insensitivity and cynicism toward the receivers of healthcare, and the lack of personal fulfillment or trend to perceive one's job in a negative way with feelings of low professional self-esteem.

The consequences of this syndrome are significant and varied and they affect mental health, physical health, quality of life, and the effectiveness of healthcare providers. This situation leads to the need for developing prevention and intervention programs aimed at monitoring and alleviating all these effects. There is only one study on this issue in Spanish pediatric ICUs. It is a study published back in 2000 by Bustinza Arriortua et al. that detailed two (2) facts as the leading causes of the burnout syndrome: institutional conflicts and work overload. Also, this study drew one interesting conclusion: about one third of the pediatric intensivists surveyed were thinking about quitting their job when they were handed out the questionnaires.28

For all these reasons, it seems evident that in the ICU setting there are no landmark studies we can read to try to understand the incidence and consequences derived from this syndrome. Society and organizations have the moral duty, ethical imperative and legal obligation to take care of the caregivers who are exposed to significant physical, emotional, and psychological loads derived from their effort and dedication to their job. To comply with this obligation, a series of basic prioritary goals should be set for the implementation of preventive and therapeutic actions.

Prevention, management, and follow-up of the post-intensive care syndromeOver the last 30 years there has been a dramatic drop in the pediatric ICU mortality rate that has dropped from 20% at the beginning of the 1980s to the actual 2%–6% today.29 This has to do with a greater knowledge of the critically ill child's diseases and conditions, with the arrival of optimal therapies, and with state-of-the-art technologies that facilitate the management of processes that seemed unapproachable in the past. Thanks to this greater capacity for health two situations that have become more and more important in the management of children arise. On the one hand, there are times that it is impossible to go back to a state prior to ICU admission, which leads to unwanted side effects and damages that, in time, and thanks to the child's greater room for improvement and right clinical support, will be partially or fully solved. On the other hand, when returning to a state prior to ICU admission won’t be possible, patients are discharged from the ICU with a total dependence on technology and they end up not being followed prospective and outpatiently by those who those who prescribed them their therapy.30

The so-called post-intensive care syndrome has barely been studied in children. Here we are talking about risk factors when requiring mechanical ventilation, renal clearance, or life-sustaining treatment in the ICU setting.31 In the adult critically ill patient, this syndrome is an entity that has been recently described and affects 30%–50% of the patients. In the case of adult patients, and even though over 50% of the patients come back to their jobs during the first year after their ICU stay, many of them require support when performing activities of daily living (ADL) for long periods of time after being discharged from the ICU. Both physical (persistent pain, ICU-acquired weakness, malnutrition, pressure ulcers, sleep disorders, need for devices) and neuropsychological symptoms (cognitive deficits—memory disorders, attention disorders, speed mental process disorders—or appearance of mental issues —anxiety, depression, or PTSD) can be seen here.

We need observational studies that define accurately the who and the what for in this group of patients Also, it seems reasonable to say that the management of this entity will require multidisciplinary teams including ICU intensivists, rehab specialists, physical therapists, nurses, psychologists, psychiatrists, occupational therapists, and speech therapists. And all them coordinated with the GP to guarantee the continuity of the healthcare process (Table 2). With this goal in mind, the creation of follow-up consultations for patients who have been discharged from the ICU is a new and interesting approach here. But this is something that has already been explored in neonatal ICUs, especially when it comes to the management of premature babies, since this allows us to take care of any unwanted side effects derived from the ICU stay and, most important of all, anticipates any possible prevalent complications in this population of patients.

Measures aimed at preventing the post-intensive care syndrome.

| A: Assessment, prevention, and management of painThe use of validated tools that can be used in all patients at all time is highly recommended |

| B: Wake up and spontaneous breathing trialsProvide analgesia when needed, but withdraw it when needed to prevent overdose and unwanted side effects |

| C: Choose analgesia and sedationThe evidence published in the medical literature helps us decide what the optimal option is based on the patient's individual circumstances |

| D: Delirium: assessment, prevention and managementThe use of validated tools that can be used in all patients at all time is highly recommended |

| E: Exercise and early mobilizationOptimize mobility and work-out for every patient based on their own capacities (through the help that someone from the ICU team may provide) in an attempt to restore mobility |

| F: Family: commitment and empoweringKeeping good communication with the family is essential in every step of the patient's clinical way and empowering the family to become part of the ICU team ensures the best possible healthcare and improves several aspects of the patient's experience. The F reminds us that the patient–family unity is at the center of the healthcare process |

Source: Taken and modified from www.icudelirium.org.

Obviously, this is one of the most controversial issues when it comes to its implementation. According to the standards and recommendations established by the Spanish Ministry of Health and Social Policy, an intensive care unit is defined as an organization of healthcare providers who provide multidisciplinary care in a specific area of the hospital and meet all functional, structural, and organizational prerequisites to ensure safety, quality, and efficiency in the management of critically ill patients.32

The infrastructure of an ICU should facilitate the healthcare process in a healthy environment to improve the physical and physichologica state of patients, healthcare providers, and families alike. We are talking about an environment that should avoid structural stress and promote a state of well-being. There are evidences on this issue that have been published in clinical practice guidelines in the United States and Europe, and also flight plans that have been designed by some nursing associations. It seems that an adequate ICU design may help reduce medical mistakes, improve the patients’ results, reduce the average ICU stay, and play a significant role in cost management.

Based on all this, changes in the arrangement of the ICU are suggested so it can be a comfortable friendly environment for patients, families and healthcare providers alike. We are talking about space where technical efficacy, quality healthcare, and comfort for everyone go hand in hand. Changes that should improve the location of the ICU, its adequacy to users, and the work flow of healthcare providers under certain conditions of light, temperature, acoustics, materials, furniture, and decoration. When it comes to children, these spaces are very compelling to patients and their families, with particularities such as neonatal ICUs.1

As a consequence of this new standard, that seems undisputed from the point of view of common sense and the goals we wish to achieve, new needs arise that not only engage us in attitudinal changes but also in greater financial investments in the ICU setting. Most ICUs need to be refurbished by intensivists who believe in what they’re trying to accomplish. Humanization, in this case, should reach the working space, something that the intensivist cannot change by himself since this is the sole responsibility of institutions. Table 3 summarizes the areas with room for improvement on this regard.

Areas for improving the architecture of intensive care units.

| Interventions with patients | Interventions on the patient's privacy | Patient's privacyIndividual wards with bathroom or close to shared bathrooms |

| Interventions to improve the patient's well-being in his environment | Adequate colors and images (pediatric patients)Natural lightFurniture | |

| Interventions to foster communications and orientation | Calendar. ClockWhite boards, alphabets, specific appsIntercommunicator with the nurse room | |

| Distractions | Reading lights in aware patientsTV setMusicWIFI networkRoom phone (optional) | |

| Avoid light, thermal, and acoustic stress | Monitor temperature and humidityMonitor lightMonitor noise | |

| Interventions in healthcare | Controlled and adequate lightingTake care of acoustics at the working placeAdequate access to documentationSystem of central monitoring with access to all screens and medical equipment for all patients admitted to the ICUPossibility, access, and monitoring by the medical and nursing personnel from all ICU terminalsMake sure that the patient can be observed and monitored at all time from nurse control with no blind spots whatsoever. The distribution of the ICU wards should be circular and nurse control should be at the center. If due to the number of ICU wards available no visual contact with every patient is possible, it is highly recommended to install videocameras for monitoring purposes | |

| Administrative and staff areas | Adequate spaces | Functional approved furniture and specifically designed for the tasks at hand. It should be easy to clean and move and it should be ergonomic to ensure proper postures and avoid unnecessary efforts in a safe wayFriendly home-like colors and furnitureIndividual lockers for the staff to leave their personal items or a change of pajamasCommunication facilities: the staff should have enough elements to be able to communicate such as computers, phones, and other systems for internal communication purposesEnvironmental well-beingRooms for restRooms to eat: an office with a stove, microwave oven, fridge, sink, table and enough chairs is required for the staff to be able to preserve, heat, or prepare their own food |

| Rooms for the staff on call | Adequate furniture (to rest and work)Adequate communication facilities: at least one direct phoneComplete bathrooms equipped with showers and mechanical ventilation systems and separated for both sexesLocker rooms for the staff's personal items | |

| Family members | SignsWaiting roomsAdequate furniture and intimacyFarewell roomRooms for family members in extremely critical situations | |

Source: Modified from the The Humanization Plan of Intensive Care Units of the Community of Madrid, 2016.

Although the main goal of ICUs is to go back, whether totally or partially, to the patient's situation prior to his admission, sometimes this cannot be done. When it comes to this, the therapeutic target needs to change: the main goal changes and is now based on alleviating suffering and providing the best possible care including end-of-life care.7,8,33,34

On this regard, the ethical committee of the Society of Critical Care Medicine establishes that “[…] palliative and intensive care are not mutually exclusive options but rather coexisting options […]” and “[…] the healthcare team has the obligation to provide therapies that alleviate the suffering originated from physical, emotional, social, and spiritual sources”.35

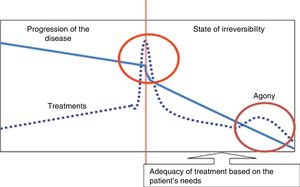

The main goal of palliative care in any clinical setting is to provide comprehensive healthcare to patients and their families so that the moment of death is “[…] free from discomfort and suffering for the patient, the family and the caregivers and in compliance with the patient's wishes and clinical, cultural, and ethical standards […]”. In this context and based on several studies, in the ICU setting, around 10%-30% of all deaths happen after the adequation of life support therapy has already started (Fig. 1).34,36

The adequation of therapies should be part of an overall palliative care plan that should include pharmacological and non-pharmacological measures targeted at the dignity, well-being, and physical, psychological and spiritual needs of patients and their families. This should be a multidisciplinary approach, and everybody involved in the administration of therapies should be in the know.1,36

The complex decisions being made with critically ill patients at the end of their lives can create controversies among healthcare providers and also between healthcare providers and family members and caregivers in the particular case of pediatric patients. Here everybody should have the tools necessary to solve these conflicts. Free open discussions are essential here to create an open, coherent and flexible team culture for the constructive discussion of all questions and worries early and after death has occurred. With this goal in mind, the integration of ICUs in the hospital setting allows us to make adequate and objective assessments of this group of patients. Also, the writing of protocols for life support therapy adequacy and its agreed implementation facilitates how to proceed in these situations. On this regard, and as something supplementary, the creation of documents in tune with the evolutionary characteristics of different diseases, conditions and patients is an obvious need too (such as, for example, the case of chronic patients, long-lasting onco-hematological or respiratory patients).3

ConclusionsAs we have already seen in this paper, humanization is a wide concept that includes multidisciplinary aspects in the management of patients and aims at putting patients and caregivers at the center of healthcare. Each and every aspect of development offers an almost undisputed possibility to improve. Who will be up to humanizing? Could someone really say that this is not necessary? Assuming as a real necessity the big picture of what we’re talking about here, we need to be cautious when dealing with all the ingredients contained in this recipe. We are confronted with a change of paradigm where intangibles -what cannot be measured- will probably surpass what is quantified and measured these days. In time the fact that we are jumping into this overhaul from an ideal setting with scarce evidence can leave everything as a bunch of words without actual evidence.

The road ahead seems clear to see but it is still to be built. As pediatricians, many parts of this road have already been completed and they will seem easy to us. But, as pediatricians, parts of the road such as those that have to do with end-of-life care after ICU admission make us have to be cautious when changing directions. Humanizing seems like a necessary thing to do and it is an adventure that requires much more than just words. They look beautiful on a piece of paper, but it takes more than just that. It takes facts to become real to be able to seriously humanize and so that it does not become just another bumper sticker.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

We wish to thank all pediatric intensivists, adult intensivists, nurses, nurse assistants, families, and patients. Also, we wish to thank the writing team of the Humanization Plan of Intensive Care Units for their accuracy and critical spirit. And finally, we wish to thank those who with very little do so much for the public healthcare system.

Please cite this article as: García-Salido A, Heras la Calle G, Serrano González A. Revisión narrativa sobre humanización en cuidados intensivos pediátricos: ¿dónde estamos? Med Intensiva. 2019;43:290–298.