To know the implementation and characteristics of non-invasive ventilation (NIV) in the Emergency Departments (EDs) of public hospitals in Catalonia (Spain) and analyze possible differences based on the typology, degree of activity and the availability of an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) in the hospital.

DesignA non-interventional, descriptive study was carried out, using a structured questionnaire divided into 3 sections: 1) professional experience and training; 2) devices used; and 3) clinical scenarios and the use of NIV.

SettingPersons responsible for public EDs in Catalonia.

ResultsFifty-two of the 54 public EDs in Catalonia responded (96.3%). Fifty-one perform NIV, which is mainly initiated by emergency care physicians (78.5%); 66.7% maintain the patient in the ED until discharge; and in 43.1% of the cases the length of stay is >24h. Of the EDs, 39.2% have their own protocol, 35.3% of which are established by consensus with other departments (more frequently in non-county hospitals [p=0.012], and centers with an ICU [p=0.014]), while 25.5% have no protocol, and 43.1% register the activity. Training represents the greatest difficulty for the implementation of NIV, but 19.6% do not provide specific training. When support is needed, the main physician of reference is the intensivist (35.3%) (more frequently in non-county hospitals [p=0.012], and centers with an ICU [p=0.002]).

ConclusionsIn most EDs in Catalonia, NIV is performed by emergency care physicians. Areas needing improvement include drainage of patients once NIV has been started, the promotion of protocols, registry of activity, and training of the healthcare professionals.

Conocer la implantación y características de la ventilación no invasiva (VNI) en los servicios de urgencias hospitalarios (SUH) públicos de Cataluña. Analizar si hay diferencias en función de la tipología, del grado de actividad y de la existencia de una unidad de cuidados intensivos (UCI) en el hospital.

DiseñoEstudio descriptivo, sin intervención, realizado mediante una encuesta estructurada en 3 bloques: 1) profesionales y formación; 2) aparataje utilizado y 3) escenarios clínicos y uso de la VNI.

ÁmbitoResponsables de los SUH públicos de Cataluña.

ResultadosContestaron 52 de 54 SUH públicos (96,3%): 51 realizan VNI, iniciada mayoritariamente por el médico de urgencias (78,5%). El 66,7% mantiene al paciente en urgencias hasta su retirada y en el 43,1% la estancia suele superar las 24h. El 39,2% de los SUH tienen un protocolo propio, el 35,3% consensuado con otros servicios (más en hospitales no comarcales, p=0,012, y con UCI, p=0,014) y el 25,5% no tiene. El 43,1% registran la actividad. El aprendizaje constituye la mayor dificultad para la implantación, pero el 19,6% no contempla la formación reglada regular. En caso de necesitar soporte, el principal médico de referencia es el especialista de Medicina Intensiva (35,3%, más en hospitales no comarcales, p=0,012, y con UCI, p=0,002).

ConclusionesLa VNI la realizan en la mayoría de los SUH los médicos de urgencias. Las áreas de mejora detectadas incluyen el drenaje de pacientes una vez iniciada la VNI, la potenciación de protocolos, el registro de actividad y la formación de los profesionales.

Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) is essential in the management of acute respiratory failure.1 Evidence of the efficacy of NIV in different scenarios was first obtained in the 1990s from clinical trials and subsequently from meta-analyses, mostly conducted in Intensive Care Units (ICUs).2–6 The scenarios with the strongest scientific evidence and highest grade of recommendation in this regard are the exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ECOPD)7 and acute heart failure (AHF).8

The use of NIV has subsequently spread to other care Units, and particularly to hospital Emergency Departments (EDs).9,10 A recent study has shown the most common scenario for the use of NIV in the ED to be AHF (38.0%), followed by ECOPD (34.2%).11 In Spain few studies offer information on the implementation of NIV and its characteristics in the ED. A study published in 2008 found NIV to be applied in 45.7% of the EDs,12 without specifying its implementation in the different Spanish Autonomous Communities, since the EDs in each Community were not detailed, and healthcare organization in Spain implies the possibility of differences among Communities. On the other hand, since 2008 the use of NIV has increased and has even reached the pre-hospital emergency care setting.13,14 In this context, the VENUR-CAT (Noninvasive ventilation in Emergency Departments in Catalonia [VENtilación no invasiva en URgencias en Cataluña]) study was designed with the purpose of knowing the implementation and characteristics of NIV in the EDs of public hospitals in Catalonia (Spain), the training of their professionals, and of analyzing possible differences based on the type of hospital, the degree of activity in the ED, and the availability of an ICU in the hospital.

MethodThe VENUR-CAT study involved a non-interventional descriptive design based on a survey. The latter was developed by the research team during three successive meetings, giving rise to a 22-item questionnaire on NIV, divided into three blocks: one referred to the professionals and training; another addressing the equipment and devices used; and a third block referred to the clinical scenarios and utilization of NIV. The study sample comprised the persons in charge of the public EDs in Catalonia, which totaled 54 at the time of the study.15 The survey was sent by e-mail using the docs.google.com platform a total of 5 times between September and December 2016. Confidentiality of the individual data of the centers was maintained, and the participants were not asked to supply personal data of the professionals in the center. All the questions of the survey had to be answered, and once completed the questionnaire could not be repeated. The non-responders were contacted by telephone to complete the survey during January 2017. The project was approved by the Ethics Committee of Bellvitge University Hospital (code PR285/16).

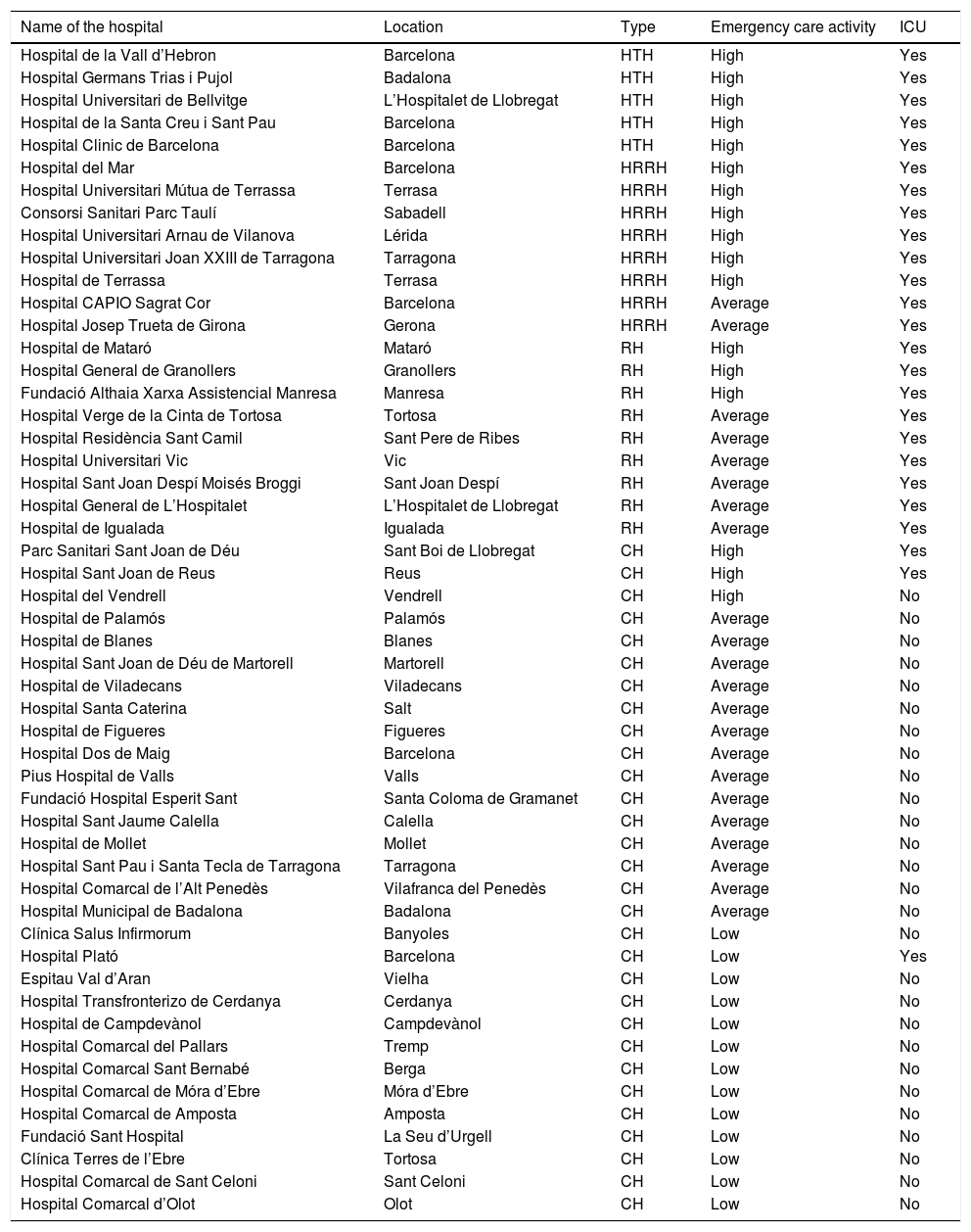

The answers to the survey were individually tabulated in a database using the SPSS version 19.0 statistical package (IBM, North Castle, NY, USA). The hospitals were classified into three categories according to emergency care activity (high activity=over 200 visits a day; average activity=100–200 visits a day; low activity=under 100 visits a day), typology (HTH: high technology hospital, HRRH: high resolution reference hospital, RH: reference hospital, CH: county hospital), and the presence of absence of an ICU (Table 1).16 In order to facilitate comparisons, the research team established dichotomic groupings of the categories emergency care activity (high or average-low activity) and hospital typology (non-county hospital [NcH] or county hospital [CH]).

Classification of the 52 public hospitals, ordered according to type, that participated in the study.

| Name of the hospital | Location | Type | Emergency care activity | ICU |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital de la Vall d’Hebron | Barcelona | HTH | High | Yes |

| Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol | Badalona | HTH | High | Yes |

| Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge | L’Hospitalet de Llobregat | HTH | High | Yes |

| Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau | Barcelona | HTH | High | Yes |

| Hospital Clinic de Barcelona | Barcelona | HTH | High | Yes |

| Hospital del Mar | Barcelona | HRRH | High | Yes |

| Hospital Universitari Mútua de Terrassa | Terrasa | HRRH | High | Yes |

| Consorsi Sanitari Parc Taulí | Sabadell | HRRH | High | Yes |

| Hospital Universitari Arnau de Vilanova | Lérida | HRRH | High | Yes |

| Hospital Universitari Joan XXIII de Tarragona | Tarragona | HRRH | High | Yes |

| Hospital de Terrassa | Terrasa | HRRH | High | Yes |

| Hospital CAPIO Sagrat Cor | Barcelona | HRRH | Average | Yes |

| Hospital Josep Trueta de Girona | Gerona | HRRH | Average | Yes |

| Hospital de Mataró | Mataró | RH | High | Yes |

| Hospital General de Granollers | Granollers | RH | High | Yes |

| Fundació Althaia Xarxa Assistencial Manresa | Manresa | RH | High | Yes |

| Hospital Verge de la Cinta de Tortosa | Tortosa | RH | Average | Yes |

| Hospital Residència Sant Camil | Sant Pere de Ribes | RH | Average | Yes |

| Hospital Universitari Vic | Vic | RH | Average | Yes |

| Hospital Sant Joan Despí Moisés Broggi | Sant Joan Despí | RH | Average | Yes |

| Hospital General de L’Hospitalet | L’Hospitalet de Llobregat | RH | Average | Yes |

| Hospital de Igualada | Igualada | RH | Average | Yes |

| Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu | Sant Boi de Llobregat | CH | High | Yes |

| Hospital Sant Joan de Reus | Reus | CH | High | Yes |

| Hospital del Vendrell | Vendrell | CH | High | No |

| Hospital de Palamós | Palamós | CH | Average | No |

| Hospital de Blanes | Blanes | CH | Average | No |

| Hospital Sant Joan de Déu de Martorell | Martorell | CH | Average | No |

| Hospital de Viladecans | Viladecans | CH | Average | No |

| Hospital Santa Caterina | Salt | CH | Average | No |

| Hospital de Figueres | Figueres | CH | Average | No |

| Hospital Dos de Maig | Barcelona | CH | Average | No |

| Pius Hospital de Valls | Valls | CH | Average | No |

| Fundació Hospital Esperit Sant | Santa Coloma de Gramanet | CH | Average | No |

| Hospital Sant Jaume Calella | Calella | CH | Average | No |

| Hospital de Mollet | Mollet | CH | Average | No |

| Hospital Sant Pau i Santa Tecla de Tarragona | Tarragona | CH | Average | No |

| Hospital Comarcal de l’Alt Penedès | Vilafranca del Penedès | CH | Average | No |

| Hospital Municipal de Badalona | Badalona | CH | Average | No |

| Clínica Salus Infirmorum | Banyoles | CH | Low | No |

| Hospital Plató | Barcelona | CH | Low | Yes |

| Espitau Val d’Aran | Vielha | CH | Low | No |

| Hospital Transfronterizo de Cerdanya | Cerdanya | CH | Low | No |

| Hospital de Campdevànol | Campdevànol | CH | Low | No |

| Hospital Comarcal del Pallars | Tremp | CH | Low | No |

| Hospital Comarcal Sant Bernabé | Berga | CH | Low | No |

| Hospital Comarcal de Móra d’Ebre | Móra d’Ebre | CH | Low | No |

| Hospital Comarcal de Amposta | Amposta | CH | Low | No |

| Fundació Sant Hospital | La Seu d’Urgell | CH | Low | No |

| Clínica Terres de l’Ebre | Tortosa | CH | Low | No |

| Hospital Comarcal de Sant Celoni | Sant Celoni | CH | Low | No |

| Hospital Comarcal d’Olot | Olot | CH | Low | No |

HTH: high technology hospital; CH: county hospital; RH: reference hospital; HRRH: high resolution reference hospital: ICU: Intensive Care Unit.

The results corresponding to qualitative variables were reported as absolute values and percentages, while quantitative variables were expressed as the mean and standard deviation (SD) in the case of a normal distribution (as determined by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test), or as the median and percentiles 25 and 75 (p25–75) in the case of a non-normal distribution. Comparisons between groups were made using the chi-squared test or applying the Fisher exact test for 2×2 contingency tables when the expected values were under 5 in the case of qualitative variables. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Kruskal–Wallis test was used in the case of quantitative variables not exhibiting a normal distribution. In all cases statistical significance was considered for p<0.05.

ResultsFifty-two of the 54 EDs completed the survey (96.3% response rate). Noninvasive ventilation was used in 51 of them (98.1%). The supervisor of the only ED that did not use NIV intended to introduce the technique in future, though difficulties related to learning of the technique were expected.

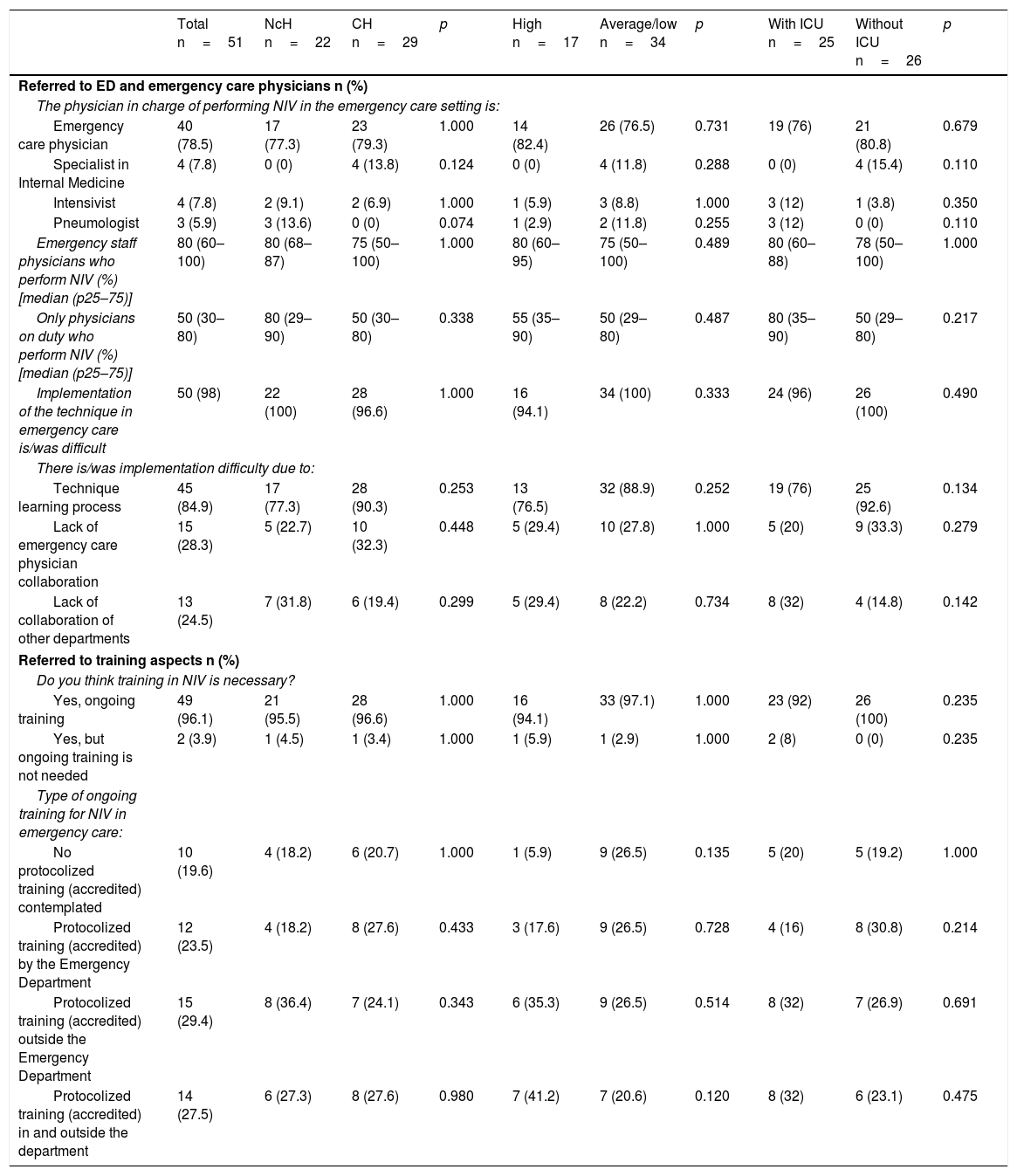

With regard to the professionals and their training (Table 2), NIV was indicated and started by the emergency care physician in 78.5% of the EDs. Eighty percent of the staff physicians 50% of the physicians on duty performed the technique personally. The difficulties for implementing the process were the learning of the technique (84.9%), and a lack of collaboration on the part of the emergency care physicians (28.3%) and physicians from other hospital departments (24.5%). The need for ongoing training was cited by 96.1% of the supervisors, and this training was imparted in similar proportions in the ED and outside the hospital–though no training was recorded in 19.6% of the centers. There were no significant differences in any of these aspects according to the type of hospital, the presence or not of an ICU, or the volume of activity of the ED.

Comparative study of professionals and training, according to the type of hospital, emergency care activity and the presence of an ICU.

| Total n=51 | NcH n=22 | CH n=29 | p | High n=17 | Average/low n=34 | p | With ICU n=25 | Without ICU n=26 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referred to ED and emergency care physicians n (%) | ||||||||||

| The physician in charge of performing NIV in the emergency care setting is: | ||||||||||

| Emergency care physician | 40 (78.5) | 17 (77.3) | 23 (79.3) | 1.000 | 14 (82.4) | 26 (76.5) | 0.731 | 19 (76) | 21 (80.8) | 0.679 |

| Specialist in Internal Medicine | 4 (7.8) | 0 (0) | 4 (13.8) | 0.124 | 0 (0) | 4 (11.8) | 0.288 | 0 (0) | 4 (15.4) | 0.110 |

| Intensivist | 4 (7.8) | 2 (9.1) | 2 (6.9) | 1.000 | 1 (5.9) | 3 (8.8) | 1.000 | 3 (12) | 1 (3.8) | 0.350 |

| Pneumologist | 3 (5.9) | 3 (13.6) | 0 (0) | 0.074 | 1 (2.9) | 2 (11.8) | 0.255 | 3 (12) | 0 (0) | 0.110 |

| Emergency staff physicians who perform NIV (%) [median (p25–75)] | 80 (60–100) | 80 (68–87) | 75 (50–100) | 1.000 | 80 (60–95) | 75 (50–100) | 0.489 | 80 (60–88) | 78 (50–100) | 1.000 |

| Only physicians on duty who perform NIV (%) [median (p25–75)] | 50 (30–80) | 80 (29–90) | 50 (30–80) | 0.338 | 55 (35–90) | 50 (29–80) | 0.487 | 80 (35–90) | 50 (29–80) | 0.217 |

| Implementation of the technique in emergency care is/was difficult | 50 (98) | 22 (100) | 28 (96.6) | 1.000 | 16 (94.1) | 34 (100) | 0.333 | 24 (96) | 26 (100) | 0.490 |

| There is/was implementation difficulty due to: | ||||||||||

| Technique learning process | 45 (84.9) | 17 (77.3) | 28 (90.3) | 0.253 | 13 (76.5) | 32 (88.9) | 0.252 | 19 (76) | 25 (92.6) | 0.134 |

| Lack of emergency care physician collaboration | 15 (28.3) | 5 (22.7) | 10 (32.3) | 0.448 | 5 (29.4) | 10 (27.8) | 1.000 | 5 (20) | 9 (33.3) | 0.279 |

| Lack of collaboration of other departments | 13 (24.5) | 7 (31.8) | 6 (19.4) | 0.299 | 5 (29.4) | 8 (22.2) | 0.734 | 8 (32) | 4 (14.8) | 0.142 |

| Referred to training aspects n (%) | ||||||||||

| Do you think training in NIV is necessary? | ||||||||||

| Yes, ongoing training | 49 (96.1) | 21 (95.5) | 28 (96.6) | 1.000 | 16 (94.1) | 33 (97.1) | 1.000 | 23 (92) | 26 (100) | 0.235 |

| Yes, but ongoing training is not needed | 2 (3.9) | 1 (4.5) | 1 (3.4) | 1.000 | 1 (5.9) | 1 (2.9) | 1.000 | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | 0.235 |

| Type of ongoing training for NIV in emergency care: | ||||||||||

| No protocolized training (accredited) contemplated | 10 (19.6) | 4 (18.2) | 6 (20.7) | 1.000 | 1 (5.9) | 9 (26.5) | 0.135 | 5 (20) | 5 (19.2) | 1.000 |

| Protocolized training (accredited) by the Emergency Department | 12 (23.5) | 4 (18.2) | 8 (27.6) | 0.433 | 3 (17.6) | 9 (26.5) | 0.728 | 4 (16) | 8 (30.8) | 0.214 |

| Protocolized training (accredited) outside the Emergency Department | 15 (29.4) | 8 (36.4) | 7 (24.1) | 0.343 | 6 (35.3) | 9 (26.5) | 0.514 | 8 (32) | 7 (26.9) | 0.691 |

| Protocolized training (accredited) in and outside the department | 14 (27.5) | 6 (27.3) | 8 (27.6) | 0.980 | 7 (41.2) | 7 (20.6) | 0.120 | 8 (32) | 6 (23.1) | 0.475 |

CH: county hospital; NcH: non-county hospital; ED: hospital Emergency Department; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; NIV: noninvasive ventilation.

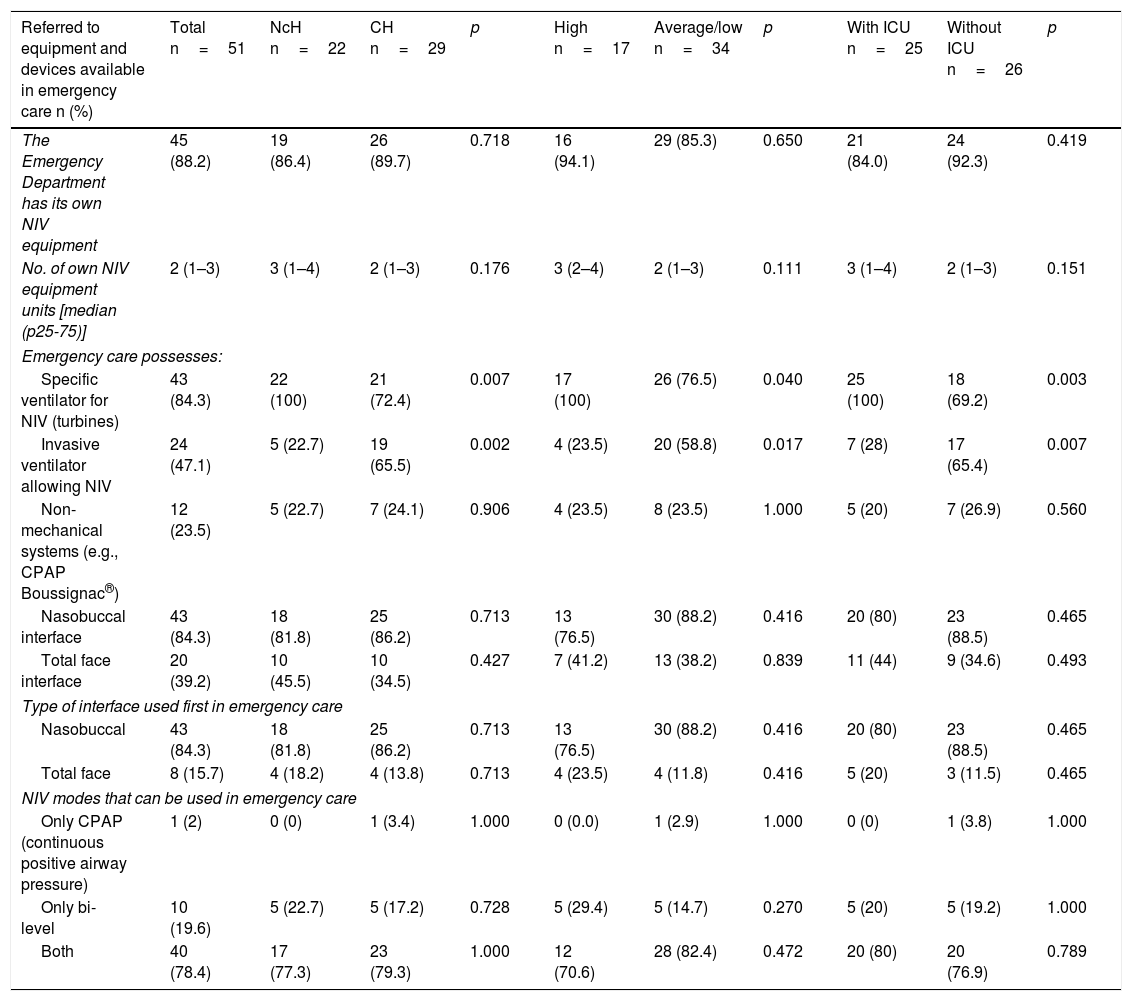

With regard to the equipment and devices used (Table 3), most of the EDs had their own means for performing NIV (88.2%), particularly specific turbine ventilators (84.3%). In turn, 84.3% of the EDs used the nasobuccal interface and 78.4% used both the continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and bi-level ventilation mode. Differences were found among the centers in terms of the type of respirator employed. In this respect, the specific ventilator was more prevalent in NcHs (100% versus 72.4%; p=0.007) and in hospitals with an ICU (100% versus 69.2%; p=0.003), as well as in centers with high emergency care activity (100% versus 76.5%; p=0.04). In contrast, invasive ventilation systems with NIV functions were more prevalent in CHs (65.5% versus 22.7%; p=0.001) and in centers without an ICU (65.4% versus 28%; p=0.007), as well as in hospitals with average/low emergency care activity (58.8% versus 23.5%; p=0.017).

Comparative study of equipment and devices, according to the type of hospital, emergency care activity and the presence of an ICU.

| Referred to equipment and devices available in emergency care n (%) | Total n=51 | NcH n=22 | CH n=29 | p | High n=17 | Average/low n=34 | p | With ICU n=25 | Without ICU n=26 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Emergency Department has its own NIV equipment | 45 (88.2) | 19 (86.4) | 26 (89.7) | 0.718 | 16 (94.1) | 29 (85.3) | 0.650 | 21 (84.0) | 24 (92.3) | 0.419 |

| No. of own NIV equipment units [median (p25-75)] | 2 (1–3) | 3 (1–4) | 2 (1–3) | 0.176 | 3 (2–4) | 2 (1–3) | 0.111 | 3 (1–4) | 2 (1–3) | 0.151 |

| Emergency care possesses: | ||||||||||

| Specific ventilator for NIV (turbines) | 43 (84.3) | 22 (100) | 21 (72.4) | 0.007 | 17 (100) | 26 (76.5) | 0.040 | 25 (100) | 18 (69.2) | 0.003 |

| Invasive ventilator allowing NIV | 24 (47.1) | 5 (22.7) | 19 (65.5) | 0.002 | 4 (23.5) | 20 (58.8) | 0.017 | 7 (28) | 17 (65.4) | 0.007 |

| Non-mechanical systems (e.g., CPAP Boussignac®) | 12 (23.5) | 5 (22.7) | 7 (24.1) | 0.906 | 4 (23.5) | 8 (23.5) | 1.000 | 5 (20) | 7 (26.9) | 0.560 |

| Nasobuccal interface | 43 (84.3) | 18 (81.8) | 25 (86.2) | 0.713 | 13 (76.5) | 30 (88.2) | 0.416 | 20 (80) | 23 (88.5) | 0.465 |

| Total face interface | 20 (39.2) | 10 (45.5) | 10 (34.5) | 0.427 | 7 (41.2) | 13 (38.2) | 0.839 | 11 (44) | 9 (34.6) | 0.493 |

| Type of interface used first in emergency care | ||||||||||

| Nasobuccal | 43 (84.3) | 18 (81.8) | 25 (86.2) | 0.713 | 13 (76.5) | 30 (88.2) | 0.416 | 20 (80) | 23 (88.5) | 0.465 |

| Total face | 8 (15.7) | 4 (18.2) | 4 (13.8) | 0.713 | 4 (23.5) | 4 (11.8) | 0.416 | 5 (20) | 3 (11.5) | 0.465 |

| NIV modes that can be used in emergency care | ||||||||||

| Only CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.4) | 1.000 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | 1.000 | 0 (0) | 1 (3.8) | 1.000 |

| Only bi-level | 10 (19.6) | 5 (22.7) | 5 (17.2) | 0.728 | 5 (29.4) | 5 (14.7) | 0.270 | 5 (20) | 5 (19.2) | 1.000 |

| Both | 40 (78.4) | 17 (77.3) | 23 (79.3) | 1.000 | 12 (70.6) | 28 (82.4) | 0.472 | 20 (80) | 20 (76.9) | 0.789 |

CH: county hospital; NcH: non-county hospital; ED: hospital Emergency Department; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; NIV: noninvasive ventilation.

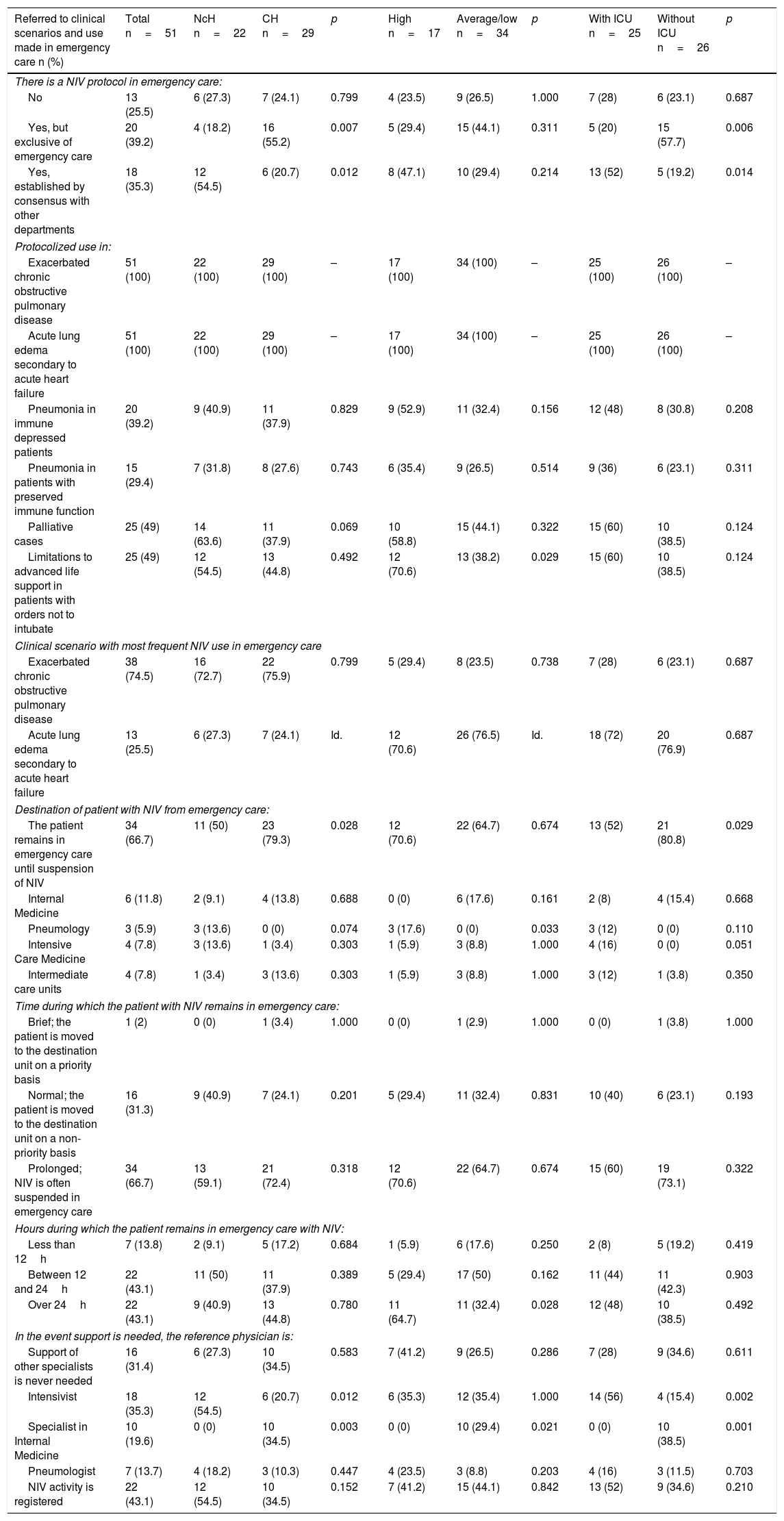

Lastly, with regard to clinical scenarios and use (Table 4), 39.2% of the EDs had protocols of their own, 35.3% had protocols established by consensus with other departments, and 25.5% had no protocol. The indications in all the centers were AHF and ECOPD, and in 49% of the departments the technique was used in patients with limitations to advanced life support (LALS). A total of 66.7% of the ED supervisors informed that NIV was withdrawn in the ED, and that the use of the technique implied prolonged admission to the department (43.1% considered patient stay to exceed 24h). In turn, 68.8% responded that support was required from other specialists in relation to NIV. In these cases, the physician most often acting as reference was the intensivist (35.3%), followed by the specialist in Internal Medicine (19.6%). The comparison among centers showed protocols established by consensus with other departments to be more prevalent in NcHs (54.5% versus 20.7%; p=0.012) and in centers with an ICU (52% versus 19.2%; p=0.014). Likewise, the use of NIV in patients with LALS was more common in high activity EDs (70.6% versus 38.2%; p=0.029), and patients receiving NIV were more frequently admitted to Pneumology in high activity EDs (17.6% versus 0%; p=0.033) and remained more often in the ED in hospitals without an ICU (80.8% versus 52%; p=0.029). With regard to the supporting specialist, the intensivist was significantly more often involved in NcHs (54.5% versus 20.7%; p=0.012) and in centers with an ICU (56% versus 15.4%, p=0.002). In contrast, the specialist in Internal Medicine was more often involved in CHs (34.5% versus 0%; p=0.003), in centers without an ICU (38.5% versus 0%; p=0.001), and in average/low activity EDs (29.4% versus 0%; p=0.021).

Comparative study of clinical scenarios and use, according to the type of hospital, emergency care activity and the presence of an ICU.

| Referred to clinical scenarios and use made in emergency care n (%) | Total n=51 | NcH n=22 | CH n=29 | p | High n=17 | Average/low n=34 | p | With ICU n=25 | Without ICU n=26 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| There is a NIV protocol in emergency care: | ||||||||||

| No | 13 (25.5) | 6 (27.3) | 7 (24.1) | 0.799 | 4 (23.5) | 9 (26.5) | 1.000 | 7 (28) | 6 (23.1) | 0.687 |

| Yes, but exclusive of emergency care | 20 (39.2) | 4 (18.2) | 16 (55.2) | 0.007 | 5 (29.4) | 15 (44.1) | 0.311 | 5 (20) | 15 (57.7) | 0.006 |

| Yes, established by consensus with other departments | 18 (35.3) | 12 (54.5) | 6 (20.7) | 0.012 | 8 (47.1) | 10 (29.4) | 0.214 | 13 (52) | 5 (19.2) | 0.014 |

| Protocolized use in: | ||||||||||

| Exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 51 (100) | 22 (100) | 29 (100) | – | 17 (100) | 34 (100) | – | 25 (100) | 26 (100) | – |

| Acute lung edema secondary to acute heart failure | 51 (100) | 22 (100) | 29 (100) | – | 17 (100) | 34 (100) | – | 25 (100) | 26 (100) | – |

| Pneumonia in immune depressed patients | 20 (39.2) | 9 (40.9) | 11 (37.9) | 0.829 | 9 (52.9) | 11 (32.4) | 0.156 | 12 (48) | 8 (30.8) | 0.208 |

| Pneumonia in patients with preserved immune function | 15 (29.4) | 7 (31.8) | 8 (27.6) | 0.743 | 6 (35.4) | 9 (26.5) | 0.514 | 9 (36) | 6 (23.1) | 0.311 |

| Palliative cases | 25 (49) | 14 (63.6) | 11 (37.9) | 0.069 | 10 (58.8) | 15 (44.1) | 0.322 | 15 (60) | 10 (38.5) | 0.124 |

| Limitations to advanced life support in patients with orders not to intubate | 25 (49) | 12 (54.5) | 13 (44.8) | 0.492 | 12 (70.6) | 13 (38.2) | 0.029 | 15 (60) | 10 (38.5) | 0.124 |

| Clinical scenario with most frequent NIV use in emergency care | ||||||||||

| Exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 38 (74.5) | 16 (72.7) | 22 (75.9) | 0.799 | 5 (29.4) | 8 (23.5) | 0.738 | 7 (28) | 6 (23.1) | 0.687 |

| Acute lung edema secondary to acute heart failure | 13 (25.5) | 6 (27.3) | 7 (24.1) | Id. | 12 (70.6) | 26 (76.5) | Id. | 18 (72) | 20 (76.9) | 0.687 |

| Destination of patient with NIV from emergency care: | ||||||||||

| The patient remains in emergency care until suspension of NIV | 34 (66.7) | 11 (50) | 23 (79.3) | 0.028 | 12 (70.6) | 22 (64.7) | 0.674 | 13 (52) | 21 (80.8) | 0.029 |

| Internal Medicine | 6 (11.8) | 2 (9.1) | 4 (13.8) | 0.688 | 0 (0) | 6 (17.6) | 0.161 | 2 (8) | 4 (15.4) | 0.668 |

| Pneumology | 3 (5.9) | 3 (13.6) | 0 (0) | 0.074 | 3 (17.6) | 0 (0) | 0.033 | 3 (12) | 0 (0) | 0.110 |

| Intensive Care Medicine | 4 (7.8) | 3 (13.6) | 1 (3.4) | 0.303 | 1 (5.9) | 3 (8.8) | 1.000 | 4 (16) | 0 (0) | 0.051 |

| Intermediate care units | 4 (7.8) | 1 (3.4) | 3 (13.6) | 0.303 | 1 (5.9) | 3 (8.8) | 1.000 | 3 (12) | 1 (3.8) | 0.350 |

| Time during which the patient with NIV remains in emergency care: | ||||||||||

| Brief; the patient is moved to the destination unit on a priority basis | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.4) | 1.000 | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | 1.000 | 0 (0) | 1 (3.8) | 1.000 |

| Normal; the patient is moved to the destination unit on a non-priority basis | 16 (31.3) | 9 (40.9) | 7 (24.1) | 0.201 | 5 (29.4) | 11 (32.4) | 0.831 | 10 (40) | 6 (23.1) | 0.193 |

| Prolonged; NIV is often suspended in emergency care | 34 (66.7) | 13 (59.1) | 21 (72.4) | 0.318 | 12 (70.6) | 22 (64.7) | 0.674 | 15 (60) | 19 (73.1) | 0.322 |

| Hours during which the patient remains in emergency care with NIV: | ||||||||||

| Less than 12h | 7 (13.8) | 2 (9.1) | 5 (17.2) | 0.684 | 1 (5.9) | 6 (17.6) | 0.250 | 2 (8) | 5 (19.2) | 0.419 |

| Between 12 and 24h | 22 (43.1) | 11 (50) | 11 (37.9) | 0.389 | 5 (29.4) | 17 (50) | 0.162 | 11 (44) | 11 (42.3) | 0.903 |

| Over 24h | 22 (43.1) | 9 (40.9) | 13 (44.8) | 0.780 | 11 (64.7) | 11 (32.4) | 0.028 | 12 (48) | 10 (38.5) | 0.492 |

| In the event support is needed, the reference physician is: | ||||||||||

| Support of other specialists is never needed | 16 (31.4) | 6 (27.3) | 10 (34.5) | 0.583 | 7 (41.2) | 9 (26.5) | 0.286 | 7 (28) | 9 (34.6) | 0.611 |

| Intensivist | 18 (35.3) | 12 (54.5) | 6 (20.7) | 0.012 | 6 (35.3) | 12 (35.4) | 1.000 | 14 (56) | 4 (15.4) | 0.002 |

| Specialist in Internal Medicine | 10 (19.6) | 0 (0) | 10 (34.5) | 0.003 | 0 (0) | 10 (29.4) | 0.021 | 0 (0) | 10 (38.5) | 0.001 |

| Pneumologist | 7 (13.7) | 4 (18.2) | 3 (10.3) | 0.447 | 4 (23.5) | 3 (8.8) | 0.203 | 4 (16) | 3 (11.5) | 0.703 |

| NIV activity is registered | 22 (43.1) | 12 (54.5) | 10 (34.5) | 0.152 | 7 (41.2) | 15 (44.1) | 0.842 | 13 (52) | 9 (34.6) | 0.210 |

CH: county hospital; NcH: non-county hospital; ED: hospital Emergency Department; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; NIV: noninvasive ventilation.

Noninvasive ventilation is performed in practically all EDs of public centers in Catalonia. This means that implementation of the technique, at least in this Autonomous Community, has been completed since the year 2008, when it was estimated that a little under one-half of all EDs in Spain used NIV (45.7%).12 This generalized implementation of NIV has undoubtedly been facilitated by technological advances in the ventilators, which are now more versatile and portable, thereby allowing them to be used in other settings such as pre-hospital emergency care and conventional hospital wards. A registry in patients with ECOPD has shown a significant increase in the use of NIV, from 1% in 1998 to 4.5% in 2008–with a concomitant decrease in invasive mechanical ventilation from 6% to 3.5% in the same period of time.17 Another registry involving 70 ICUs in France showed a significant increase in the use of NIV in different clinical scenarios over a period of only 5 years, from 16% in 1997 to 23% in 2002 (p<0.001).18 However, this increased use of NIV does not appear to be so significant in the case of AHF. In effect, the EAHFE registry, which analyzes 5845 episodes of AHF in three different periods, revealed an incidence of NIV utilization ranging from 3.2% in 2007 to 6% in 2009 and 4.5% in 2011 (p=0.24).19

Our data coincide with those published by Andreu-Ballester et al.12 in that the emergency care physician is the professional who generally performs NIV in the ED. We likewise coincide in the greater use of the nasobuccal interface, which offers important advantages in terms of convenience of use,20 and in the greater utilization of specific ventilators for performing NIV. This aspect is understandable: the current performance of these ventilators results in improved patient tolerance and effectively compensates air leakage, reducing asynchronies, improving the ventilator-patient relationship and thus ensuring increased success of the technique. The ICU ventilators designed for invasive ventilation in turn offer performances allowing them to be used also for NIV. Nevertheless, the difficulty of compensating leakage is an important limitation to the use of these systems–though such problems are increasingly less relevant thanks to the technological developments. A third category of ventilators has recently been introduced, offering shared performance (ICU ventilation and specific NIV) and allowing polyvalent use in different scenarios–particularly in relation to patient transfer.21 This would explain the increased presence of ICU ventilators in EDs of CHs and of hospitals with average or low activity, since they afford increased polyvalence, and in the event mechanical ventilation proves necessary the same ventilator can still be used.

Acute heart failure and ECOPD are the clinical scenarios in which NIV is most often used. In both cases the technique reduces patient mortality and the need for intubation. It therefore forms part of first line patient management, with a maximum level of evidence.9,10 In clinical practice it is in these scenarios where NIV proves most useful and offers greater patient benefit. In this respect, a survey of 132 EDs in the United States (with a 90% response rate) assessed NIV in three clinical scenarios–exacerbated asthma, ECOPD and AHF–and concluded that according to physician opinion, the technique is most useful in the latter two scenarios (p<0.001).22 Moreover, in these scenarios mortality is lower when compared with other NIV application settings,23 and this consequently inspires a degree of confidence among the professionals. Nevertheless, it must be remembered that the need for NIV identifies patients at increased risk of suffering adverse events.24

The management of patient stay is of great importance for EDs.25 In this regard, NIV is associated to prolonged admission: 86.2% of the EDs surveyed in our study reported a stay of over 12h, and in 66.7% of the cases NIV was suspended in the ED. The VNICat registry, involving the participation of 11 EDs in Catalonia, and which consecutively documented 159 NIV episodes during a one-month period in the ED, offers higher objective values, with an 83.1% incidence of NIV withdrawal in the ED. The authors associated this to deficiencies in management continuity of the technique.11 A study carried out in four Canadian hospitals and involving 618 patients requiring ventilatory support in the ED–484 invasive mechanical ventilation (78.3%), 118 NIV (19.1%), and 16 both (2.6%)–reported longer median stays in the ED among the patients subjected to NIV (16.6h, interquartile range [IQR]: 8.2–27.9) than in those subjected to mechanical ventilation alone (4.6h, IQR: 2.2–11.1) or both techniques (15.4h, IQR: 6.4–32.6). The authors attributed this difference in stay to the stabilization period usually seen in such patients, causing them to be left under observation and thus avoid needless admission to the ICU.26 This circumstance is even more notorious on considering that it is in the high activity hospitals of the VENUR-CAT study, where patient drainage should be more adequate, in which there are more patients with stays exceeding 24h. These are the centers where we find a greater percentage of patients subjected to LALS–the latter being a further reason underlying prolonged admission. In many hospitals, in situations of LALS, the patient is not considered a candidate for admission to the ICU, and is kept under observation in the ED. This practice is very debatable, however, since LALS should not be seen as a contraindication to ICU admission, though it can be understandable in the face of a progressively increasing ICU demand.27,28 This circumstance has already been described in the setting in which our study has been carried out, and the imbalance between ICU demand and number of available beds complicates early admission to intensive care, and can even imply that critical patients are unable to be admitted to the ICU–this situation in turn being associated to poorer prognostic outcomes.29

Our study describes a low incidence of NIV protocols established by consensus with other hospital departments. A possible solution to prolonged ED stay would be fluid communication and collaboration among the different participants in the NIV management process–this strategy having been shown to offer improved outcomes in other scenarios with use of the so-called lean method.30,31

Two aspects amenable to improvement are professional training and registry of the activity carried out. A large percentage of the responders in our study considered that difficulties implementing the technique are a consequence of problems associated to the learning process. If adequate training in the technique is not provided and knowledge of the technology is lacking, and an efficacy registry is moreover not kept, the impression is that NIV is of little help. In this regard, a survey of 46 Italian hospitals found the percentage registry of results to be very low (15%), and the perceived usefulness of the technique was poor, since 73% of those interviewed considered that NIV was able to avoid intubation in less than one-half of the cases.32 Another study by the same authors, involving nurses outside the ICU but who in principle could make use of NIV, found that only 13% considered training in NIV to be adequate, and pointed to the need for further training.33 The basic premise of NIV is to be well informed about the indications of the technique, how it is carried out, patient monitoring, ventilator technology and expendable materials use.34,35

The present study has several limitations. A first limitation refers to the method, since this is an opinion survey of the persons in charge of the EDs, who might not be involved in clinical practice, and therefore may have a less exact view of NIV than those involved in patient care. We consider that this does not constitute a major limitation, however, since these department supervisors are in charge of material resources, training organization, registries and protocols. Another possible limitation is that we have only considered public hospitals. In this regard, in Catalonia, private centers globally account for 16% of all ED consultations.16 We therefore are unable to analyze the situation referred to NIV use in these EDs. A further aspect not contemplated in our study is patient care continuity between the pre-hospital and the hospital setting, though implementation at hospital level in the studied setting is not very high.11

In conclusion, our study shows that NIV has been fully implemented in the public EDs of Catalonia, and that the technique is fundamentally performed by the emergency care physician, though there is room for organizational improvement closely related to the management of time and the continuity of patient care. The existence of protocols and support from the specialist in Internal Medicine is more prevalent in county hospitals and in centers with an ICU. More protocols established by consensus with other departments are needed in order to facilitate the transfer of these patients to the ICU or to intermediate care units in situations of prolonged NIV. Improved training efforts and activity registries are also needed.

Authorship/collaborationsSigning author contribution has been as follows:

- •

Javier Jacob: design of the investigation, design of the survey questions, statistical analysis and drafting of the manuscript.

- •

José Zorrilla: design of the investigation, design of the survey questions and drafting of the manuscript.

- •

Emili Gené: design of the investigation, design of the survey questions and drafting of the manuscript.

- •

Gilberto Alonso: design of the investigation, design of the survey questions and drafting of the manuscript.

- •

Pere Rimbau: design of the investigation, design of the survey questions and drafting of the manuscript.

- •

Francesc Casarramona: design of the investigation, design of the survey questions and drafting of the manuscript.

- •

Cristina Netto: design of the investigation, design of the survey questions and drafting of the manuscript.

- •

Pere Sánchez: design of the investigation, design of the survey questions and drafting of the manuscript.

- •

Ricard Hernández: design of the investigation, design of the survey questions and drafting of the manuscript.

- •

Xavier Escalada: design of the investigation, design of the survey questions and drafting of the manuscript.

- •

Òscar Miró: design of the investigation, design of the survey questions, statistical analysis and drafting of the manuscript.

None.

Thanks are due to the supervisors of the Emergency Departments of Catalonia for their participation, and to Alicia Díaz for her field work in relation to the interviews. The present study received support from the Societat Catalana de Medicina d’Urgències i Emergències (SoCMUE) limited to covering the administrative costs of the survey.

Please cite this article as: Jacob J, Zorrilla J, Gené E, Alonso G, Rimbau P, Casarramona F, et al. Ventilación no invasiva en los servicios de urgencias hospitalarios públicos de Cataluña. Estudio VENUR-CAT. Med Intensiva. 2018;42:141–150.