The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has created new scenarios that require modifications to the usual cardiopulmonary resuscitation protocols. The current clinical guidelines on the management of cardiorespiratory arrest do not include recommendations for situations that apply to this context. Therefore, the National Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Plan of the Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine and Coronary Units (SEMICYUC), in collaboration with the Spanish Group of Pediatric and Neonatal CPR and with the Teaching Life Support in Primary Care program of the Spanish Society of Family and Community Medicine (SEMFyC), have written these recommendations, which are divided into five parts that address the main aspects for each healthcare setting. This article consists of an executive summary of them.

La pandemia por SARS-CoV-2 ha generado nuevos escenarios que requieren modificaciones de los protocolos habituales de reanimación cardiopulmonar. Las guías clínicas vigentes sobre el manejo de la parada cardiorrespiratoria no incluyen recomendaciones para situaciones aplicables a este contexto. Por ello, el Plan Nacional de Reanimación Cardiopulmonar de la Sociedad Española de Medicina Intensiva, Crítica y Unidades Coronarias, en colaboración con el Grupo Español de RCP Pediátrica y Neonatal y con el programa de Enseñanza de Soporte Vital en Atención Primaria de la Sociedad Española de Medicina Familiar y Comunitaria, ha redactado las siguientes recomendaciones, que están divididas en cinco partes que tratan los principales aspectos para cada entorno asistencial. En este artículo se presenta un resumen ejecutivo de las mismas.

The situation created by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has given rise to new scenarios that require changes in the usual cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) protocols while keeping the aim of ensuring that patients who suffer cardiorespiratory arrest (CA) receive the best care without placing the safety of the attending healthcare professionals at risk.

The current clinical guides on the management of CA of the European Resuscitation Council (ERC), the American Heart Association (AHA) or the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) do not offer recommendations referred to situations applicable in this context. With the aim of covering this new scenario, the National Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Plan (Plan Nacional de Reanimación Cardiopulmonar [PNRCP]) of the Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine and Coronary Units (Sociedad Española de Medicina Intensiva, Crítica y Unidades Coronarias [SEMICYUC]), in collaboration with the Spanish Group of Pediatric and Neonatal CPR (Grupo Español de RCP Pediátrica y Neonatal) and the Teaching Life Support in Primary Care program (Enseñanza de Soporte Vital en Atención Primaria [ESVAP]) of the Spanish Society of Family and Community Medicine (Sociedad Española de Medicina Familiar y Comunitaria [SEMFyC]), has produced a series of recommendations on the approach to CA in patients with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, in any location and applicable to all healthcare professionals, based on a review of the available scientific evidence, and as an expert opinion consensus document. Nevertheless, we are aware that this is merely a starting point that needs to be adapted to the local contexts and updated on the basis of new evidence that will arise in future, given the dynamic nature of the pandemic.

Part 1. Safety issues during cardiopulmonary resuscitation in patients with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infectionTypes of transmission and precautionsRespiratory infections can be transmitted through respiratory droplets (measuring 5−10 µm in diameter) or droplet nuclei (measuring < 5 µm in diameter).1 Transmission through droplets takes place via the following mechanisms: direct / close contact (< 1−2 m) with a symptomatic individual, secondary to exposure of the conjunctival and airway mucosa to respiratory droplets; or indirect contact with fomites (objects or surfaces) contaminated by respiratory droplets in the surroundings of the patient.

Airborne transmission through droplet nuclei is different, and is related to persistent suspension in the air of these minute droplets during prolonged periods of time.

According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), SARS-CoV-2 can fundamentally transmit between people through respiratory droplets and contact. In this context, and in addition to the standard precautions, protective measures should include specific protective elements against transmission through contact and through respiratory droplets. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, such transmission may occur under specific conditions characterized by the generation of aerosols, through procedures that can mechanically induce their generation and dispersion (manual ventilation with mask and self-inflating balloon, nebulization, aspiration of secretions or noninvasive mechanical ventilation) or procedures which generate aerosols directly within the airway (orotracheal intubation, chest compression during CPR maneuvering).1–3

Recommendations on protective strategiesIn addition to the standard measures, the specific protective considerations when evaluating CA in a patient with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection should include measures against transmission though contact, through respiratory droplets, and in relation to aerosol-generating activities.4,5

As regards personal protective equipment (PPE), due consideration must be made of the aforementioned mechanisms of transmission, with the inclusion of:

Protective clothing and glovesThe purpose of these elements is to protect against splashing by biological fluids or secretions during resuscitation maneuvering. Furthermore, in situations of high viral transmission risk, it seems reasonable and prudent to intensify the protective measures.6,7

- •

We recommend the use of integral protective equipment such as full body suits or long-sleeved impermeable suits that can be combined with integrated or removable hoods for protection of the head, and shoe coverings. If full body suits or long-sleeved impermeable suits are not available, the use of clinical aprons made of plastic or some other impermeable material should be considered.6

- •

We recommend the use of double gloves during airway access procedures, followed by disposal of the outer gloves.8

- •

When evaluating an individual with COVID-19 who suffers clinical deterioration, we recommend the use of surgical masks or, ideally, FPP2 masks, regardless of the location of the patient.9

- •

Since CPR involves techniques capable of generating aerosols with a high viral transmission risk, we recommend the use of FPP2 masks or, ideally, FPP3 masks, regardless of the location of the patient.7,8

- •

It is advisable to remove the respiratory protective equipment last, once the rest of the PPE elements have been removed and, if possible, outside the patient room.6,7

We recommend the use in all cases of disposable eye protection devices such as integral goggles (preferably), screens or hoods - both when evaluating patients with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 that suffer clinical worsening, and during CPR maneuvering, which can generate aerosols. Eye protective measures are advised due to the risk of eye contamination from splashing or droplets.7,9

Ideally, disposable equipment should be used. If this is not possible, then the protective equipment is to be placed in adequate bags or containers for decontamination following the instructions of the manufacturer.6–9

General considerations- •

It is advisable to clearly inform about the infectious status of the patient with CA at the time of activation of the resuscitation team, whenever new members are incorporated to the team, and when moving the patient to the Unit of destination.10–12

- •

We recommend keeping the number of people conforming the resuscitation team as low as possible in order to minimize exposure.7,8,10,12

- •

All members of the resuscitation team involved in dealing with the patient must make use of the recommended PPE, following the established fitting and removal standards and protocols, and always under due supervision.6–8,10,12 It is crucial for ALL the healthcare staff involved in addressing CA to have received the necessary training – ideally based on clinical simulation methods – for use of the EPI.7

- •

Ideally, the utilization of disposable / single-use PPE is advised. If this is not possible, then disinfection of the equipment is to be considered, with strict adherence to the recommendations of the manufacturer.6–8

- •

It is advisable to have resuscitation kits with all the basic material to perform complete advanced resuscitation, together with adequate PPE for each member of the team dealing with CA.10 In order to prevent cross-contamination, it is advisable to avoid moving CA karts, defibrillators, etc. between different areas of the hospital.

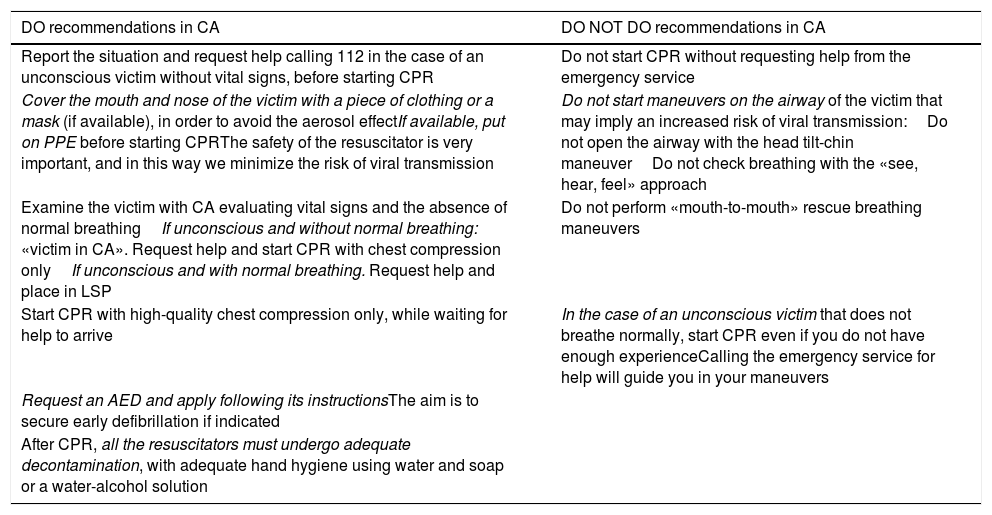

In the context of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, a possible case is defined as a patient with signs of mild acute respiratory infection in which no microbiological diagnostic tests have been made.6 In the community setting, the existing recommendations and prudence should cause us to consider any patient with CA as a victim with possible SARS-CoV-2 infection. Taking into account that 70% of all cases of out-hospital CA occur in the home of the patient, it is possible that the first intervening person may have been exposed to SARS-CoV-2. Based on these premises, our recomendations10,12 are those described in Table 1 and Appendix Bla Fig. 1 (supplementary material).

“Do / do not do” recommendations in the case of community cardiac arrest.

| DO recommendations in CA | DO NOT DO recommendations in CA |

|---|---|

| Report the situation and request help calling 112 in the case of an unconscious victim without vital signs, before starting CPR | Do not start CPR without requesting help from the emergency service |

| Cover the mouth and nose of the victim with a piece of clothing or a mask (if available), in order to avoid the aerosol effectIf available, put on PPE before starting CPRThe safety of the resuscitator is very important, and in this way we minimize the risk of viral transmission | Do not start maneuvers on the airway of the victim that may imply an increased risk of viral transmission:Do not open the airway with the head tilt-chin maneuverDo not check breathing with the «see, hear, feel» approach |

| Examine the victim with CA evaluating vital signs and the absence of normal breathingIf unconscious and without normal breathing: «victim in CA». Request help and start CPR with chest compression onlyIf unconscious and with normal breathing. Request help and place in LSP | Do not perform «mouth-to-mouth» rescue breathing maneuvers |

| Start CPR with high-quality chest compression only, while waiting for help to arrive | In the case of an unconscious victim that does not breathe normally, start CPR even if you do not have enough experienceCalling the emergency service for help will guide you in your maneuvers |

| Request an AED and apply following its instructionsThe aim is to secure early defibrillation if indicated | |

| After CPR, all the resuscitators must undergo adequate decontamination, with adequate hand hygiene using water and soap or a water-alcohol solution |

AED: automated external defibrillator; PPE: personal protection equipment; CA: cardiorespiratory arrest; LSP: lateral safety position; CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

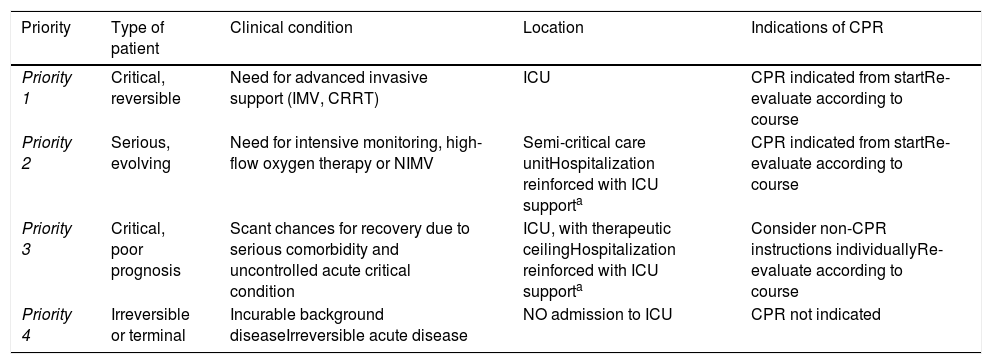

When dealing with any patient admitted to hospital, and from the time of arrival, an individualized management strategy should be planned according to the clinical conditions of the patient, the general recommendations adapted to the local setting, the wishes of the patient, and the criteria of the specialists at all the healthcare levels involved in management of the patient – including the consideration of non-resuscitation instructions.13–17

The SEMICYUC and other scientific societies have proposed a care priority model based on the patient capacity to survive conditioned to the clinical situation, comorbidities and availability of resources, seeking to secure the maximum possible benefit for the largest number of individuals possible in abidance with the principles of proportionality and distributive fairness.15Table 2 summarizes this model, adding specific considerations referred to non-resuscitation instructions for each priority.

Indications of cardiopulmonary resuscitation according to care priority profile.

| Priority | Type of patient | Clinical condition | Location | Indications of CPR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Priority 1 | Critical, reversible | Need for advanced invasive support (IMV, CRRT) | ICU | CPR indicated from startRe-evaluate according to course |

| Priority 2 | Serious, evolving | Need for intensive monitoring, high-flow oxygen therapy or NIMV | Semi-critical care unitHospitalization reinforced with ICU supporta | CPR indicated from startRe-evaluate according to course |

| Priority 3 | Critical, poor prognosis | Scant chances for recovery due to serious comorbidity and uncontrolled acute critical condition | ICU, with therapeutic ceilingHospitalization reinforced with ICU supporta | Consider non-CPR instructions individuallyRe-evaluate according to course |

| Priority 4 | Irreversible or terminal | Incurable background diseaseIrreversible acute disease | NO admission to ICU | CPR not indicated |

CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CRRT: continuous renal replacement therapy; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; IMV: invasive mechanical ventilation; NIMV: noninvasive mechanical ventilation.

Due to the complexity of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the work overload of Intensive Care Units (ICUs), it is not uncommon in areas and wards outside critical care to find patients in more serious condition than usual. These patients must be closely monitored to detect possible clinical worsening, provide timely and opportune treatment, and not delay transfer to the ICU, as part of the measures for preventing CA in high-risk individuals.13

In comparison with the classical practice of alerting the team on duty when extreme monitoring data are detected, monitoring based on early alert scales – particularly the NEWS2 scale – can contribute to the early identification of patients at risk of suffering a poor course and of needing critical care.18,19

Management of patients with clinical deterioration during the COVID-19 pandemicThe first step in patient evaluation is implementation of the pertinent general and specific protection measures, already commented above, allowing a safe approach to patients with clinical worsening, and limiting the intervention to the minimum necessary number of staff members, in order to reduce contacts.16,20,21

At the time when patient worsening is detected, help from the nearest colleague is to be requested, with the evaluation of vital signs.16,22

If no such signs are present, the support team is to be notified immediately, explaining the COVID-19 status of the patient with CA, and CPR is to be started following the corresponding in-hospital protocol.

In the presence of vital signs, the exploration is to be completed with the D-ABCDE approach (Appendix B Fig. 2 and 3 of the supplementary material), which proposes the structured evaluation and management of the clinical problems in order of priority referred to vital body systems, with the purpose of ensuring prompt detection and treatment of those problems that may prove fatal over the short term – arresting patient worsening and the development of CA, and gaining time to allow a duly trained team to start definitive management.5,8,23,24

Part 4. Adaptation of algorithms and techniques in the advanced life support (ALS) setting in patients with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infectionA schematic representation of this adaptation is found in Appendix B Fig. 4 of the supplementary material.

Evaluation of cardiorespiratory arrest- -

Before starting resuscitation maneuvering, the team must make use of PPE affording adequate protection against techniques with a high aerosol generation potential.

- -

Once adequately protected, the presence of CA is to be confirmed, assessing the patient response to stimuli and the presence of spontaneous ventilation and pulse. The “see, hear, feel” maneuver for assessing the presence of breathing is not advised,16,22 since it implies closeness between the airway of the healthcare professional and that of the patient. This risk can be avoided by reliable explorations made at a greater distance, such as palpation or inspection of chest breathing motion.

- •

Guarantee a safe environment.

- •

The members of the resuscitation team should be limited to the minimum number needed to assist the patient. If the intervention of other non-healthcare staff proves necessary, they should make use of PPE if coming into contact with the patient.

- •

Following the confirmation of CA, we recommend early activation of the advanced life support (ALS) team, placing priority on oxygenation and isolation of the airway with an endotracheal tube and cuff.

- •

D-ABCDE approach.

- •

Early activation of the ALS team is required: place priority on oxygenation and advanced airway management, ideally using an endotracheal tube with cuff.

- •

It is advisable to have a CPR kit / bag with the material needed for ALS, dedicated exclusively to that COVID-19 area.

- •

The members of the resuscitation team should be limited to the minimum number needed to assist the patient.

- •

If the patient is subjected to invasive monitoring, cardiac arrest will be considered when all the screen tracings are flat (artery, central venous pressure [CVP], pulsioximetry, capnography).25,26

- •

Quality chest compression should be started as soon as possible, but not before the resuscitator puts on the required PPE.

- •

Continuous compressions are required until advanced airway management becomes possible, ideally with the use of endotracheal intubation.

- •

In centers with experience and availability, we recommend the use of mechanical chest compression, as this reduces the number of intervening professionals during CPR maneuvering.12

The defibrillator (manual or automated) should be used as soon as possible. In the case of witnessed CA with defibrillable rhythm, and in those situations where a defibrillator can be applied immediately for defibrillation and the resuscitator has not been able to put on the corresponding PPE to start CPR, it is reasonable to follow the recommendation of applying three consecutive discharges without previous chest compression or compression between discharges. It has not been shown that defibrillation is able to generate infective aerosols; defibrillation therefore can be applied by individuals with PPE not including measures against aerosol generation, while the resuscitation team puts on the corresponding PPE to then start the management of CA.

- •

Use adhesive patches to avoid direct contact with the patient.

- •

In the event of witnessed arrest with defibrillable rhythm, the resuscitator first should put on the PPE, and then the adhesive patches should be placed and the defibrillator applied.

- •

It is advisable to place patches in patients with conduction alterations and/or risk antecedents. The risk of both tachyarrhythmias and bradycardia may be greater in relation to the drugs used for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection (prolonged QT interval) and the clinical instability of these patients with severe respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)(hypoxemia, need for profound sedation and paralysis, hemodynamic alterations).

In the context of advanced airway management during CPR, we recommend the following:

- •

Priority is to be placed on oxygenation and ventilation strategies with a low risk of generating aerosols:

- -

Avoid the use of manual ventilation with mask and self-inflating balloon before intubation.

- -

Apply HEPA (high efficiency particulate air) filters both in the self-inflating balloon and in the respirators before ventilating the patient.

- -

After analyzing the rhythm and defibrillating any ventricular arrhythmia, patients in cardiac arrest are to be intubated with endotracheal tube with cuff, as soon as possible.

- -

- •

Minimize failed orotracheal intubation attempts.

- -

Decide the person and the strategy for ensuring successful intubation at the first attempt.

- -

Suspend chest compression during intubation.

- -

- •

Consider the use of videolaryngoscopy as first option (if available), since it can reduce the number of laryngoscopy attempts, as well as avoid closeness with the airway – thereby reducing exposure to aerosols.12,27

- •

If intubation is delayed, consider ventilation with a self-inflating balloon and/or the insertion of a supraglottic device – both with HEPA filters.

- •

In already intubated patients, we should adjust the respirator parameters to the situation of CPR. Although there is no evidence for recommending concrete parameters or settings, beyond increasing FiO2 to 1 with a respiratory frequency (RF) of 10 rpm, in line with the general recommendations, pressure-control modes have been suggested, with positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) and inspiratory pressure values allowing venous return and a tidal volume (TV) of approximately 6 ml/kg during chest compression,12 turning off the trigger in order to avoid auto-trigger with the compressions, hyperventilation and trapping.

- •

In the case of orotracheal intubation due to severe respiratory worsening, and in addition to the abovementioned considerations, the following are advised:

- -

Rapid intubation sequence (RIS); this allows intubation in under 1 min, thereby avoiding ventilation with the self-inflating balloon.

- -

In the case of failed intubation or difficult airway, we should follow the DAS guidelines on unexpected difficult airway – ensuring the safety of the medical team at all times.28

- -

- •

We recommend the use of capnography whenever possible.13

The idea of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in prone decubitus (P-CPR) was first proposed by McNeil in 1989.29 Since then a number of studies and experiences have been published on this subject.30–34

Chest compression- •

Intubated patients in prone decubitus:

- -

In order to avoid the generation of aerosols and minimize viral transmission during CPR, we recommend starting chest compression with compression on the thoracic spine without sternal support, over vertebral segments T7-T10.12,35

- -

After obtaining signs of return of spontaneous circulation (RSC), we advise returning the patient to supine decubitus.

- -

- •

Non-intubated patients in prone decubitus:

- -

We recommend placing the patient in supine decubitus and continuing CPR.12

- -

- •

Patients in prone decubitus in the operating room:

- -

If compression over the thoracic spine is contraindicated (surgical incision, known previous lesions), we recommend the two-hands technique in the space between the scapula and the dorsal spine.33

- -

We should follow the recommendations in the general considerations regarding the defibrillation of patients with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. In this case, placement of the adhesive patches will differ, positioning them on the left axillary midline and right scapula, or in both axillary regions.35

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation under ECMOThere are not enough data on the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for the rescue of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection.12 The approach depends on the experience of the center and its conditions in terms of the number of available ICU beds, since the current pandemic generates a great healthcare burden, with scarce available resources.

DrugsThere is no evidence to suggest a change in the indications, timing of administration or dosage of drugs with respect to the general algorithm.

It is important to remember that patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection are often treated with drug substances that prolong the QT interval (hydroxychloroquine, antiretrovirals, azithromycin, levofloxacin, metoclopramide, etc.) or predispose to the appearance of conduction block (darunavir/cobicistat), either alone or in combination with amiodarone.

Although the contraindication of amiodarone in combination with these drugs is referred to chronic treatments, we should consider the alternative use of lidocaine.24,36 If CA is suspected to be secondary to ventricular fibrillation / pulseless ventricular tachycardia due to QT prolongation or torsades de pointes, amiodarone would be contraindicated, and the use of magnesium sulfate would be advisable.

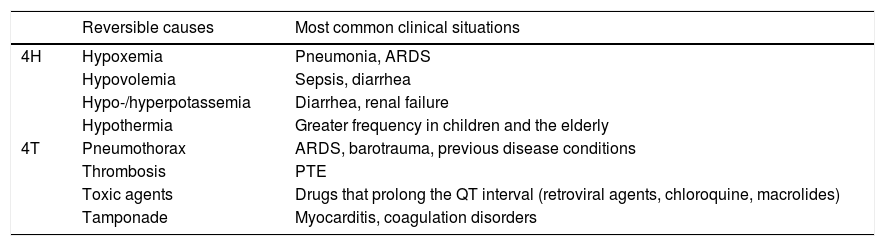

Reversible causesWhen considering and correcting the cause of CA, hypoxia, thrombosis and drug toxicity – particularly due to the direct effect of antivirals and interactions with them – are of particular importance. Clinical suspicion and the ultrasound findings are the basis of the diagnosis, particularly in relation to pulmonary thromboembolism. Management does not differ from that applicable in other patients, beyond the aspects mentioned in the section on drug toxicity in treatment of the infection.13Table 3 summarizes the most prevalent reversible causes in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Potential reversible causes of cardiac arrest in patients with COVID-19.

| Reversible causes | Most common clinical situations | |

|---|---|---|

| 4H | Hypoxemia | Pneumonia, ARDS |

| Hypovolemia | Sepsis, diarrhea | |

| Hypo-/hyperpotassemia | Diarrhea, renal failure | |

| Hypothermia | Greater frequency in children and the elderly | |

| 4T | Pneumothorax | ARDS, barotrauma, previous disease conditions |

| Thrombosis | PTE | |

| Toxic agents | Drugs that prolong the QT interval (retroviral agents, chloroquine, macrolides) | |

| Tamponade | Myocarditis, coagulation disorders |

ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; PTE: pulmonary thromboembolism.

The suspension of CPR is guided by the same considerations as in CA due to other causes. The decision should be made once it becomes clear that continuing CPR will not prove successful.17

Part 5. Management of cardiorespiratory arrest in pediatric patients during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemicThese recommendations (Appendix B Fig. 5 of the supplementary material) are a complement to those established in the roadmap and generic document of the SEMICYUC. With respect to all that is not included in this part, and in the event of doubt, the recommendations applicable to adults will apply – except in the case of newborn infants.

Before cardiorespiratory arrestRegarding the initial considerations to be taken into account before CA, we recommend the following12,16,37:

- •

The start of CPR may be delayed due to difficulties in continuous physical presence monitoring and the need to make use of PPE.

- •

The staff must be aware that in the case of CA, the number of resuscitators should be limited to a maximum of four. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation should only begin once the resuscitators have put on their PPE, which in turn must be effective in protecting against aerosols.

- •

We recommend having the CPR and difficult airway intubation material at hand and near to all critically ill children with coronavirus infection. Each Unit should establish the adequate place and make sure that all the staff members are familiarized with the location and content.

- •

We suggest CA and CPR simulations in children with SARS-CoV-2 infection, ideally in the work setting and with the routine human and material resources.

- •

In the presence of treatment adaptation – limitation instructions including the non-initiation of CPR, the decision is to be reflected in the case history and must be known to the assisting professionals.

- •

In order to adapt care in children with CA, a number of different scenarios can be described12,16,37:

In the community: assistance by citizens. Basic life support- •

It should be considered by default that the child may be infected with SARS-CoV-2, and thus represents a contagion risk for the resuscitators.

- •

We recommend the general sequence of basic CPR, with some modifications, and remembering the priority of ventilation in pediatric CPR.38

- •

If the resuscitators live with the child, they are likely to also be infected; the general sequence of basic CPR therefore can be applied.

- •

The “see, hear, feel” maneuver should be simplified, reducing it to only “see”, in order to reducing the risk of contagion.

- •

Mouth-to-mouth or mouth-to-mouth/nose insufflation can be done through a surgical mask or, if not available, using a cloth mask or piece of clothing.

- •

If the resuscitator is not willing to perform ventilations, at least continuous chest compressions should be made.

In a healthcare center: assistance by professionals with resources. Advanced life support

- •

The person assisting the child should alert his/her colleagues and start CPR immediately. We recommend keeping the number of resuscitators to the minimum necessary. In general, it is advisable to limit the team to four people, who should put on their aerosol-proof PPE before beginning CPR, and should start intervening as they become adequately prepared.

Example of the distribution of roles with four resuscitators:

- -

Non-intubated patient. Supervisor: coordination and supervision of PPE; Supervisor + Resuscitator 2: airway and ventilation; Resuscitator 3: chest compression; Resuscitator 4: monitoring and administration of drugs and fluids.39

- -

Intubated patient. Supervisor: coordination and contact with the exterior; Resuscitator 2: connection-adjustment of the respirator, monitoring-defibrillation and takeover of chest compression; Resuscitator 3: chest compression; Resuscitator 4: administration of drugs and fluids, and recording of events.39

General care of the newborn infant with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in the delivery room should follow the current algorithms referred to stabilization, transition support, resuscitation and oxygen therapy,40 taking into account the following particularities:

- •

It is advisable to reinforce the newborn infant and healthcare staff isolation and protection measures during delivery and possible transfer.41 Transfer to and stay in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) should be in a closed incubator.

- •

We recommend minimizing aerosol-generating procedures such as the aspiration of secretions.

- •

The indicated ventilation device remains a T-piece respirator, with the fitting of a filter to the mask. As an alternative, use can be made of a self-inflating bag, likewise equipped with a filter.

- •

Early intubation and videolaryngoscopy are not indicated in these cases, though protection of the resuscitator with a face screen is necessary. Tubes without a balloon are to be used (and if equipped with a balloon, the latter should not be insufflated).

- •

If necessary, surfactant can be administered using a closed system.

- •

After confirming the instructions, the relatives will be informed (generally the parents), and one of them (or both, if possible) will be allowed to spend some last few moments with the patient, after putting on the required PPE.

- •

Child without invasive ventilation:

- -

We recommend the usual pediatric CPR protocol, ventilating with bag and mask.42 If possible, four-hands ventilation should be performed: one person should affix the bag well to the face with both hands, and the other should operate the self-inflating bag, which is to be fitted with an antibacterial and antiviral filter in the connection with the face mask. The use of an oropharyngeal cannula should be considered.

- -

After 5 rescue insufflations, chest compression should be applied in the absence of vital signs or a pulse frequency of under 60/min with signs of poor perfusion.

- -

We recommend tracheal intubation as soon as possible and performed by the person with greatest experience, using videolaryngoscopy, and maximizing operator safety with a face screen. After intubation, the child should be connected immediately to the respirator, which should be prepared for use.

- -

- •

Child with invasive ventilation:

- -

We recommend adjustment of the respirator parameters. As reference: pressure mode, FiO2 1, limit pressure to secure a tidal volume that expands the chest (approximately 6 ml/kg of ideal body weight), turn off the trigger, adjust the respiratory frequency to 10−12 rpm, adjust PEEP and alarms.

- -

We recommend starting continuous chest compression without turning off the respirator, and always keeping the number of resuscitators to the minimum necessary.

- -

- •

If the child is small and can be placed in the supine position quickly and without risks, CPR should be performed with the patient in supine decubitus.

- •

In the rest of cases, although the efficacy of CPR in prone decubitus is subject to debate, the defibrillation patches should be placed in the anterior-posterior position, with the start of chest compression in prone decubitus, placing the hands at the level of vertebral bodies T7−10.

- •

If early intubation does not prove possible, we can consider using supraglottic devices, ensuring good sealing.

- •

In adolescents, and provided the team is trained in its use, a mechanical chest compression system may be considered.

- •

No recommendation has been established on CPR based on extracorporeal cardiopulmonary support in this situation; the indication should be decided on an individualized basis.

None.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez Yago MA, Alcalde Mayayo I, Gómez López R, Parias Ángel MN, Pérez Miranda A, Canals Aracil M, et al. Recomendaciones sobre reanimación cardiopulmonar en pacientes con sospecha o infección confirmada por SARS-COV-2 (COVID-19). Resumen ejecutivo. Med Intensiva. 2020;155:566–576.

This article is an executive summary of the full document to be published jointly on the website of the PNRCP: https://semicyuc.org/el-plan-nacional-de-rcp.