Vasospasm-induced late brain ischemia is one complication of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) that can be present in 30% of the patients and is associated with high morbimortality.1 A small percentage of cases do not respond to the recommended treatment with induced hypertension or interventional procedures such as brain angioplasty and the infusion of intraarterial vasodilators, and to this day there are no effective options available when all these therapies fail. We hereby describe a case of refractory vasospasm where stellate ganglion anesthetic block was used with good results.

Sixty-one-year-old patient without a significant medical history admitted due to sudden headache, nausea, and photophobia of 4-day duration due to SAH (WFNS III) following one ruptured aneurysm in the anterior communicating artery. Upon the patient's arrival to the ER, he showed right hemiparesis with brachial predominance and dysphasia that was recovered after the IV administration of nimodipine, fluid therapy, and noradrenaline. Twenty-four hours after admission, one coronary arteriography was conducted followed by the adequate embolization of the aneurysm. During the test, the presence of significant vasospasm was confirmed and it was treated with the local infusion of 2mg of nimodipine in both anterior cerebral arteries and left middle cerebral artery (MCA), and in the left pericallosal artery where 2 additional mg of nimodipine were instilled followed by one balloon angioplasty with good final angiographic results. After completing the procedure, the presence of 3/5 hemiparesis was confirmed in the patient's right arm without dysphasia that improved after increasing the arterial blood pressure.

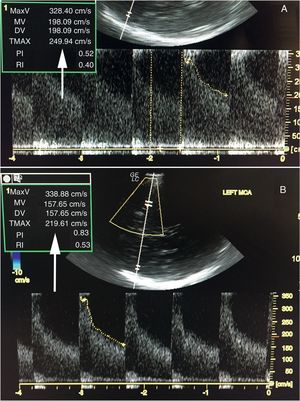

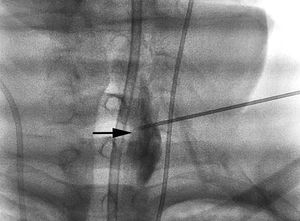

The following 48h included left focality-related fluctuating events and evidence of severe vasospasms in the transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasound with mean velocities of up to 250cm/s in the left MCA and Lindegaard ratio>3. On the third day, the angiography was repeated with a new infusion of 8mg of nimodipine but this time with partial results. The computed tomography scan performed revealed the presence of one small left frontal ischemic lesion. Due to the lack of clinical improvement (right arm paralysis and dysphasia), the Pain Treatment Unit was contacted to perform one left cervical stellate ganglion block procedure that was conducted 4 days after admission and under X-ray imaging (Fig. 1). One bolus of 10ml of bupivacaine at 0.5% was administered and one IV cannula was inserted for the repeated administration of the drug every 12h. Thirty minutes after the block, the right arm partially recovered its strength and the naming of objects improved as well. At that time, the TCD confirmed that mean velocity was reduced 10% in the left MCA (Fig. 2A and B) and that it gradually decreased over the following hours. After 3 days on bupivacaine (6 doses), the patient showed minimum brachial claudication, and no speech disorder. Cervical block was removed without symptom relapse and reduced velocity on the TCD ultrasound of up to 70% with respect to its highest value.

The pathophysiology of cerebral vasospasm is still under discussion but there are numerous theories on this issue: prolonged arterial vasoconstriction, vasoactive neuropeptide release, structural changes in the arterial wall or an exaggerate inflammatory response.2,3 If not diagnosed early, the narrowing of the arterial lumen can increase vascular resistance and reduce blood flow to the brain leading to irreversible cerebral ischemia. There are several factors associated with the appearance of vasospasm. Among the most important ones we find the volume of blood flow in the subarachnoid space (Fisher grading scale), the neurological status on admission (the Hunt–Hess scale or WFNS scales) and the size and location of the aneurysm.4

According to the last recommendations established by the AHA,5 in the presence of focal symptoms indicative of vasospasm, treatment should be based on inducing hypertension (class I, level B) and using intravascular techniques through cerebral angioplasty and/or selective infusion of intraarterial vasodilators (class IIIa, level B). No study recommends the use of any other therapies with enough level of evidence. In cases of vasospasm refractory to these treatments, several different options have been suggested such as the intrathecal administration of vasodilating drugs, the use of a continuous perfusion of intraarterial nimodipine or the stellate ganglion block.6,7

The stellate ganglion regulates the sympathetic tone of head, neck, and upper extremities; its anesthetic block is indicated to control neuropathic pain, in cases of phantom limb pain, hyperhidrosis or vascular failure of upper extremities such as Raynaud's phenomenon due to its vasodilating effect.8 The stellate ganglion block has been used successfully for the management of refractory vasospasm in isolated cases or series of cases; these show that, after the stellate ganglion block using a local anesthetic (usually bupivacaine), there is clinical improvement with partial or complete recovery of neurologic deficit since there is more blood flow coming to the cerebral arteries that are ipsilateral to the block being this effect more significant in younger patients.9,10

In order to perform this technique an adequate anatomical knowledge is essential. We should be paying attention here to the correlation between the cervical sympathetic ganglion chain and other muscle structures (scalene muscles; longus colli muscle, etc.), the esophagus, the trachea, and the neurovascular bundle (recurrent laryngeal nerve, subclavian and vertebral arteries). The technique is ultrasound-or-fluoroscopy guided. The longus colli muscle is the muscle reference, it is lateral to the ganglion and it is between 5mm and 10mm thick in the C6, and 8mm and 10mm thick in the C7. After the block, the denervation of head and neck structures occurs. The signs suggestive of successful blocks are the unilateral appearance of Horner's syndrome, anhidrosis, nasal congestion (Guttman's sign), conjunctival congestion, vein dilatation, and temperature increases of at least 1°C.6 This technique has few complications such as dysphonia or dysphagia, damage to the brachial plexus, hematomas, phrenic nerve block or epidural injection of the drug.

In sum, our case confirms that the stellate ganglion block may be a useful technique as a second-line therapy for the management of SAH-related late cerebral ischemia, especially when the vasospasm is of unilateral predominance.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez Arguiano J, Hernández-Hernández MA, Jáuregui Solórzano RA, Maldonado-Vega S, González Mandly A, Burón Mediavilla J. Bloqueo del ganglio estrellado como terapia de rescate en el vasoespasmo refractario tras hemorragia subaracnoidea. Med Intensiva. 2019;43:437–439.