With the aim of minimizing variability in critical patient care, the Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine and Coronary Units (Sociedad Española de Medicina Intensiva, Crítica y Unidades Coronarias [SEMICYUC]) has recently published its recommendations on “what to do” and “what not to do”, endorsed by the corresponding Working Groups (WGs).1,2 The management of patients with central nervous system (CNS) disease is a clear example reflecting the need to standardize the treatment protocols.3

From the Neurointensive and Trauma Care WG of the SEMICYUC, we decided to conduct a survey of neurocritical patient care with the aim of knowing the characteristics of the Departments of Intensive Care Medicine (DICMs) that manage such patients and the availability of the different techniques, as well as of analyzing certain controversial aspects in the clinical management of the disorders involved (traumatic brain injury [TBI], vertebral and spinal cord injury, non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage [SAH] and acute hemorrhagic and ischemic cerebrovascular disease [ACVD]). Scientific endorsement of the SEMICYUC was obtained. No approval from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee was considered necessary, in view of the voluntary and anonymous nature of participation in the study, which moreover did not involve the compilation of patient information. The survey was submitted to the Heads of Department on 7 November 2018, allowing an open reply period of three months. In the event of a duplicate response, that obtained first was entered in the analysis of results. The data obtained were subjected to descriptive statistical analysis, with calculation of the number (percentage) or median (interquartile range [IQR]). The present study reports the findings referred to patients with CNS trauma.

We received 45 replies with four duplicates; the valid responses thus totaled 41 (response rate 22.3%). The responding centers are indicated in Annex A (Supplementary material). The survey was answered by Heads of Department (36.6%), Section chiefs (19.5%) and staff physicians (43.9%). The hospitals were largely public (90.9%), university-related (85.4%), reference centers in Neurosurgery (80.5%) and of third level (61%), with training of residents in Intensive Care Medicine (75.6%). The median (IQR) number of hospital beds was 650 (480), while the number of DICM beds was 19 (14). A total of 68.3% of the centers monitored quality indicators.

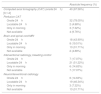

The availability of imaging techniques and interventional radiology resources is summarized in Table 1. With regard to point-of-care techniques, the availability in the participating centers was: intracranial pressure (ICP) (80.5%), jugular vein oxygen saturation (46.3%), tissue pressure (53.7%), transcranial doppler/duplex (90.2%), near-infrared spectroscopy (26.8%), intermittent (92.7%) or continuous electroencephalography (17.1%) and cerebral microdialysis (4.9%). With regard to clinical management, 61% of the centers administered antibiotic prophylaxis in neurocritical patients with diminished consciousness. The rehabilitation starting time was: first week (43.9%), 1–3 weeks (46.3%) and >3 weeks (9.8%).

Availability of imaging techniques and interventional radiology resources in the participating hospitals.

| Absolute frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

| Computed axial tomography (CAT) (onsite 24h) | 40 (97.56%) |

| [0,1-2] | |

| Perfusion CAT | |

| Onsite 24h | 32 (78.05%) |

| Locatable 24h | 2 (4.88%) |

| Only in morning | 3 (7.32%) |

| Not available | 4 (9.76%) |

| Brain and spinal cord MRI | |

| Onsite 24h | 18 (43.90%) |

| Locatable 24h | 8 (19.51%) |

| Only in morning | 13 (31.71%) |

| Not available | 2 (4.88%) |

| Interventional radiology, bleeding control | |

| Onsite 24h | 7 (17.07%) |

| Locatable 24h | 21 (51.22%) |

| Only in morning | 6 (14.63%) |

| Not available | 7 (17.07%) |

| Neurointerventional radiology | |

| Onsite 24h | 6 (14.63%) |

| Locatable 24h | 19 (46.34%) |

| Only in morning | 3 (7.32%) |

| Not available | 13 (31.71%) |

A total of 31 centers (75.6%) assisted patients with TBI. The median (IQR) patients per year seen in the participating centers was 47 (35). The intensivist supervised initial care in 67.7% of the cases.

A total of 90.3% of the centers provided anti-seizure prophylaxis according to the Brain Trauma Foundation guidelines. In turn, 64.5% of the participating centers reported ICP monitoring in 76–100% of all patients with structural damage and a Glasgow coma score <9. In 92.9% of the cases, ICP was monitored using an intra-parenchymal sensor. Noradrenalin was the drug used to secure the brain perfusion pressure targets (100%).

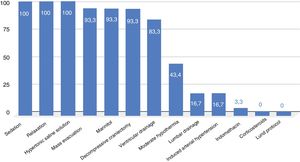

The treatments used for ICP control are summarized in Fig. 1. In the event of hyperventilation, the pressure range was 31−35mmHg in 95.5% of the cases. A total of 74.2% reported a specific management protocol. In turn, 45.2% had participated in multicenter studies over the last 5 years.

Vertebral and spinal cord injuryA total of 28 centers (70.7%) treated patients with vertebral and spinal cord injuries. The median (IQR) patients per year seen in the participating centers was 5 (5). The intensivist supervised initial care in 55.2% of the cases.

High-dose corticosteroids were routinely used by 34.5% of the centers. Likewise, 75.9% sought to secure normal pressure values (mean blood pressure [MBP] 65−70mmHg), while 24.1% resorted to induced arterial hypertension (MBP 85−90mmHg). Noradrenaline was the drug of choice for the management of spinal shock (96.6%).

Spinal fixation time: first 24h (14.8%), 24h-7 days (63%) and >7 days (22.2%). A total of 25.9% of the participating centers performed dural sac decompression in 76–100 % of their patients within the first 24h; 31.2% had a specific management protocol. In turn, 6.9% had participated in multicenter studies over the last 5 years.

Based on the results obtained, the management of TBI was seen to be homogeneous, probably as a result of good implementation of the successive editions of the Brain Trauma Foundation guidelines.4 Adherence to the guidelines proved variable and was associated to the grade of recommendation, with greater adherence in relation to the medical treatment recommendations, in more seriously ill patients, and in the reference centers.5

Greater variability was observed in the management of patients with vertebral and spinal cord injury. One out of every three centers used high-dose corticosteroids, in line with the results of the NASCIS studies. These studies were strongly criticized, however.6,7 Furthermore, corticosteroid use is associated to an increased number of complications.8 In this regard, the Neurointensive and Trauma Care WG of the SEMICYUC issued a “do not use” recommendation referred to routine corticosteroid administration in patients with vertebral and spinal cord injury.2 Regarding pressure management, only one out of every four centers elevated MBP to 85−90mmHg in the early phase. This strategy could be used as a treatment alternative, particularly in cervical spin injuries.9 A more notorious observation is the limited number of centers (25.9%) that reported dural sac decompression in the first 24h in 76–100% of their patients. This procedure was evaluated in the STASCIS trial, and was associated to neurological improvement at 6 months.10 These results, together with the limited number of centers with a specific management protocol, reflect the need for further training in this devastating condition, in order to reduce the variability of the treatments used. Grouping patients in specialized reference centers, and the use of specific registries, could improve the outcomes.

As the main limitation of our study, mention must be made of the low response rate. The information obtained by the survey therefore might not reflect routine practice in all Spanish DICMs.

The authors are grateful to all the centers that participated in the survey.

Please cite this article as: Llompart-Pou JA, Barea-Mendoza JA, Pérez-Bárcena J, Sánchez-Casado M, Ballesteros-Sanz MA, Chico-Fernández M et al. Encuesta de atención al paciente neurocrítico en España. Parte 1: Traumatismos del sistema nervioso central. Med Clin (Barc). 2021;45:250–252.