To analyze the variables associated with ICU refusal decisions as a life support treatment limitation measure.

DesignProspective, multicentrico.

Scope62 ICU from Spain between February 2018 and March 2019.

PatientsOver 18 years of age who were denied entry into ICU as a life support treatment limitation measure.

InterventionsNone.

Main interest variablesPatient comorities, functional situation as measured by the KNAUS and Karnosfky scale; predicted scales of Lee and Charlson; severity of the sick person measured by the APACHE II and SOFA scales, which justifies the decision-making, a person to whom the information is transmitted; date of discharge or in-hospital death, destination for hospital discharge.

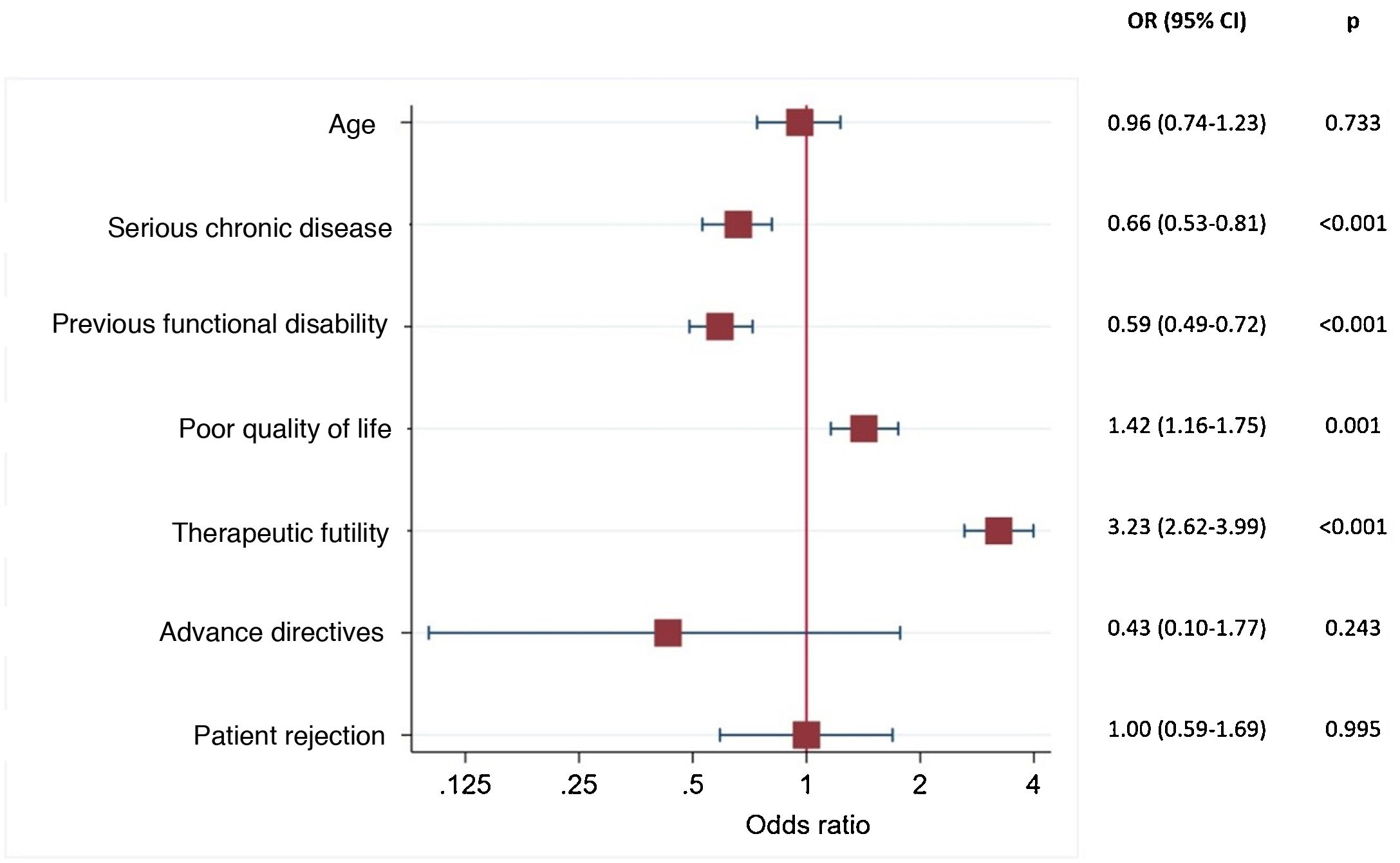

ResultsA total of 2312 non-income decisions were recorded as an LTSV measure of which 2284 were analyzed. The main reason for consultation was respiratory failure (1080 [47.29%]). The poor estimated quality of life of the sick (1417 [62.04%]), the presence of a severe chronic disease (1367 [59.85%]) and the prior functional limitation of patients (1270 [55.60%]) were the main reasons for denying admission. The in-hospital mortality rate was 60.33%. The futility of treatment was found as a risk factor associated with mortality (OR: 3.23; IC95%: 2.62–3.99).

ConclusionsDecisions to limit ICU entry as an LTSV measure are based on the same reasons as decisions made within the ICU. The futility valued by the intensivist is adequately related to the final result of death.

Analizar las variables asociadas a las decisiones de rechazo al ingreso en una Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos (UCI) como medida de limitación de tratamiento de soporte vital.

DiseñoProspectivo, multicéntrico.

ÁmbitoSesenta y dos UCI de España entre febrero de 2018 y marzo de 2019.

PacientesMayores de 18 años a los que se les negó el ingreso a una UCI como medida delimitación de tratamiento de soporte vital.

IntervencionesNinguna.

Variables de interés principalesComorbilidades de los pacientes, situación funcional previa medida por la escala KNAUS y Karnosfky; escalas pronósticas de Lee y Charlson; gravedad del enfermo medida por las escalas APACHE II y SOFA, motivo que justifica la toma de la decisión, persona a la cual es trasmitida la información; fecha de alta o fallecimiento intrahospitalario, destino al alta hospitalaria.

ResultadosSe registraron un total de 2.312 decisiones de no ingreso como medida de limitación del tratamiento de soporte vital (LTSV), de las cuales se analizaron 2.284. El principal motivo de consulta fue la insuficiencia respiratoria (1.080 [47,29%]). La pobre calidad de vida estimada de los enfermos (1.417 [62,04%]), la presencia de una enfermedad crónica grave (1.367 [59,85%]) y la limitación funcional previa de los pacientes (1.270 [55,60%]) fueron los principales motivos esgrimidos para denegar el ingreso. La tasa de mortalidad intrahospitalaria fue del 60,33%. La futilidad del tratamiento se constató como factor de riesgo asociado a mortalidad (OR: 3,23; IC 95%: 2,62–3,99).

ConclusionesLas decisiones para limitar el ingreso en UCI como medida de LTSV se basan en los mismos motivos que las decisiones tomadas dentro de la UCI. La futilidad valorada por el intensivista se relaciona adecuadamente con el resultado final de muerte.

The limitation of life support treatment (LLST) is increasingly frequent in countries in our setting.1 It is regarded as good medical practice, since therapeutic obstinacy and the maintenance of futile treatment measures lacks ethical or scientific justification.2,3

In some cases the decision not to admit a patient to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) is considered to be a form of LLST, and multiple considerations may be involved in such a decision.2,4 However, despite efforts to develop consensus documents and clinical practice guides with the aim of unifying criteria regarding patient admission to the ICU,5 some authors have criticized the lack of information on the processes underlying the acceptance or refusal of admission to intensive care.6,7 Few studies to date have focused on defining the main variables that influence the subsequent in-hospital mortality of these patients.8,9

The present multicenter study was carried out to describe the variables that intervene in the decision to reject admission to the ICU as an LLST measure; determine the frequency and types of such decisions; and analyze the factors associated to in-hospital mortality in these individuals, conducting patient follow-up for up to 90 days of hospital stay, until hospital discharge, or until the death of the patient — whichever occurs first.

Material and methodsStudy designThe ADENI-ICU is a prospective, multicenter observational study. The patient registry was opened in February 2018 — the first patient being recruited on 7 February and the last patient on 18 March. The follow-up period ended on 12 May 2019. The patients were recruited from 62 Departments of Intensive Care Medicine (DICMs) on a consecutive basis over a period of 6 months.

The limited literature on the refusal of admission to the ICU as an LLST measure complicated prior calculation of the study sample size. By extrapolating the results of the ADMISSIONREA study,20 involving 11 French ICUs that recorded 51 patients considered “too ill” to benefit from admission to the ICU over a period of one month, an estimated sample size of approximately 1700 patients could be established.

The study included patients over 18 years of age and considered by the intensivist to not be candidates for admission to the ICU as an LLST measure. The latter was defined as the decision to refuse admission, made by the intensivist evaluating the patient, and supported by one or a combination of the following conditions: advanced patient age, the presence of serious chronic disease, previous functional limitation, estimated poor quality of life, treatment futility, the existence of a justifying living will or advance directives, or patient rejection in person.

Likewise, cases of in-hospital cardiac arrest in which the decision was made to suspend resuscitation as an LLST measure were also documented.

Data collection and study variablesA registry form in paper format was used to collect the study data, followed by entry of the information in an electronic database to create a single registry corresponding to all the participating centers.

The study variables included patient clinical and demographic data (age, gender, usual place of residency, associated comorbidities [supplementary material in electronic format], previous functional status as assessed by the KNAUS10 and Karnofsky scores,11 reason for hospital admission, previous hospital admissions and admissions to the ICU), parameters related to consultation (time, location of the patient at the time of consultation, consulting person, reason for consultation [supplementary material in electronic format] and time elapsed from admission to the time of consultation, and application of the Lee12 and Charlson prognostic scales13), variables related to the decision to refuse admission (patient severity as assessed by the APACHE II14 and SOFA scores,15 the physician making the decision and his/her years of professional experience, time and reason justifying the decision made, the person to which the information was transmitted [relative or patient], degree of agreement and registry in the case history), and evolutive parameters (date of discharge or in-hospital death, patient destination at hospital discharge, and possible changes in the decision to refuse admission, with the corresponding reason).

Patient follow-upThe patients were subjected to follow-up for up to 90 days of hospital stay, until hospital discharge, or until the death of the patient — whichever occurs first.

The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee (CREC) of the reference center. Subsequently, the required documentation was forwarded to the rest of the participating centers to allow approval to be obtained from their respective CRECs. The study only started once the required approval had been obtained from all the centers.

The study was endorsed by the Scientific Committee of the Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine and Coronary Units (Sociedad Española de Medicina Intensiva, Crítica y Unidades Coronarias [SEMICYUC]).

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis of the study sample was made. The results were reported as percentages in the case of categorical variables and as the mean and standard deviation (SD) in the case of continuous quantitative variables.

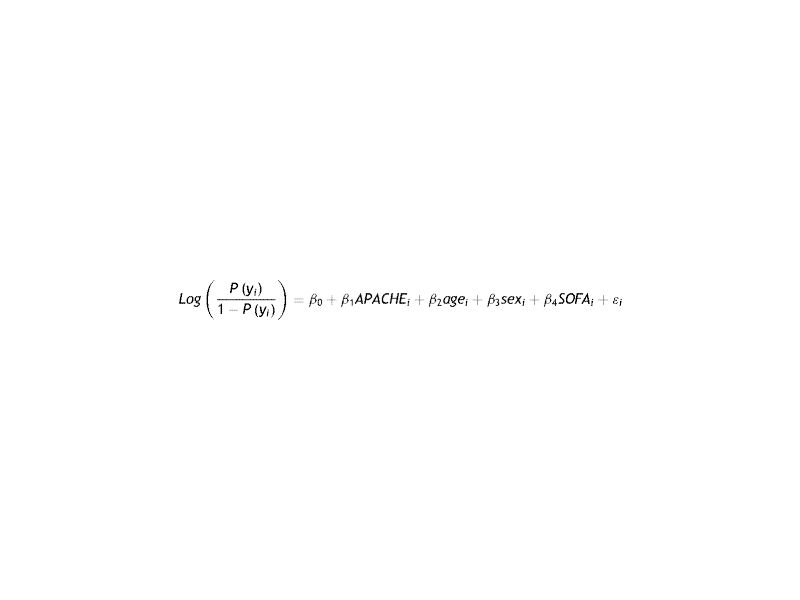

Associations between the different variables and in-hospital mortality were analyzed, with a maximum follow-up of 90 days. Since patients admitted to the same hospital and to hospitals of the same province usually share similar procedures and protocols, we were unable to assume independence between patients. Consequently, triple-level nested logistic regression analysis was performed: province, hospital and patient. To summarize, usual logistic regression models the relationship between a variable such as for example the APACHE score and the probability of death expressed as:

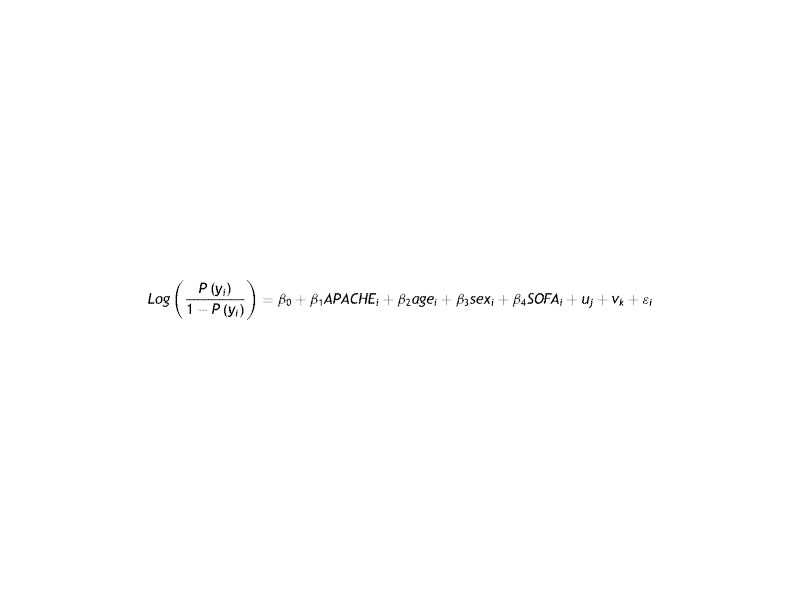

where P(yi) is the probability of death of the patient i; age, gender and the SOFA score take values for each patient; and … is random error. In this formula, the natural logarithm provides the ratio of probabilities of death for each additional point of the APACHE score.However, logistic regression requires independence between observations. Since this cannot be assumed in our study, we performed triple-level nested logistic regression analysis: province, hospital and patient. In this case, the relationship between the APACHE score and the probability of death included three random errors, one for each level of analysis:

where uj is the random error for the interception due to the province and vk is the random error for the interception due to the hospital. The interpretation of the β parameters is the same as before.The results of the mentioned analysis of association are reported as odds ratios (ORs) with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (95%CI) corrected for age, gender, APACHE II score and the SOFA scale.

The Stata version 15.1 statistical package was used throughout.

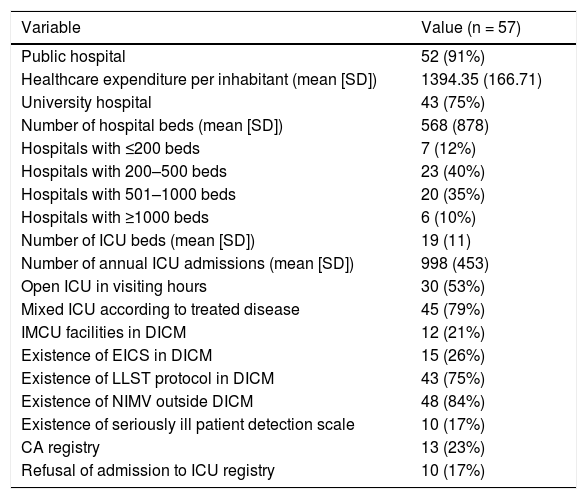

ResultsDuring the study we recorded 2312 decisions of non-admission to the ICU as an LLST measure among the 62 participating centers. The characteristics of the participating centers and Departments (5 failed to supply the required data) are reported in Table 1. Following review of the data, 28 decisions were excluded due to errors in data collection. The final number of analyzed decisions was therefore 2284.

Characteristics of 57 of the 62 hospitals and Departments of Intensive Care Medicine participating in the study.

| Variable | Value (n = 57) |

|---|---|

| Public hospital | 52 (91%) |

| Healthcare expenditure per inhabitant (mean [SD]) | 1394.35 (166.71) |

| University hospital | 43 (75%) |

| Number of hospital beds (mean [SD]) | 568 (878) |

| Hospitals with ≤200 beds | 7 (12%) |

| Hospitals with 200–500 beds | 23 (40%) |

| Hospitals with 501–1000 beds | 20 (35%) |

| Hospitals with ≥1000 beds | 6 (10%) |

| Number of ICU beds (mean [SD]) | 19 (11) |

| Number of annual ICU admissions (mean [SD]) | 998 (453) |

| Open ICU in visiting hours | 30 (53%) |

| Mixed ICU according to treated disease | 45 (79%) |

| IMCU facilities in DICM | 12 (21%) |

| Existence of EICS in DICM | 15 (26%) |

| Existence of LLST protocol in DICM | 43 (75%) |

| Existence of NIMV outside DICM | 48 (84%) |

| Existence of seriously ill patient detection scale | 10 (17%) |

| CA registry | 13 (23%) |

| Refusal of admission to ICU registry | 10 (17%) |

SD: standard deviation; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; IMCU: Intermediate Care Unit; EICS: Extended Intensive Care Service; LLST: limitation of life support treatment; DICM: Department of Intensive Care Medicine; NIMV: noninvasive mechanical ventilation; CA: cardiac arrest.

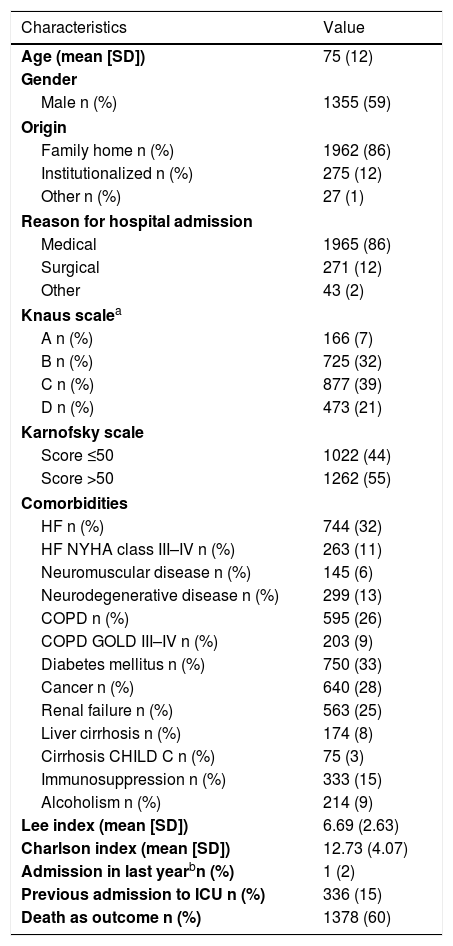

The main clinical-epidemiological variables of the study sample are shown in Table 2.

Main clinical-epidemiological characteristics of the 2284 patients analyzed in the study.

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (mean [SD]) | 75 (12) |

| Gender | |

| Male n (%) | 1355 (59) |

| Origin | |

| Family home n (%) | 1962 (86) |

| Institutionalized n (%) | 275 (12) |

| Other n (%) | 27 (1) |

| Reason for hospital admission | |

| Medical | 1965 (86) |

| Surgical | 271 (12) |

| Other | 43 (2) |

| Knaus scalea | |

| A n (%) | 166 (7) |

| B n (%) | 725 (32) |

| C n (%) | 877 (39) |

| D n (%) | 473 (21) |

| Karnofsky scale | |

| Score ≤50 | 1022 (44) |

| Score >50 | 1262 (55) |

| Comorbidities | |

| HF n (%) | 744 (32) |

| HF NYHA class III–IV n (%) | 263 (11) |

| Neuromuscular disease n (%) | 145 (6) |

| Neurodegenerative disease n (%) | 299 (13) |

| COPD n (%) | 595 (26) |

| COPD GOLD III–IV n (%) | 203 (9) |

| Diabetes mellitus n (%) | 750 (33) |

| Cancer n (%) | 640 (28) |

| Renal failure n (%) | 563 (25) |

| Liver cirrhosis n (%) | 174 (8) |

| Cirrhosis CHILD C n (%) | 75 (3) |

| Immunosuppression n (%) | 333 (15) |

| Alcoholism n (%) | 214 (9) |

| Lee index (mean [SD]) | 6.69 (2.63) |

| Charlson index (mean [SD]) | 12.73 (4.07) |

| Admission in last yearbn (%) | 1 (2) |

| Previous admission to ICU n (%) | 336 (15) |

| Death as outcome n (%) | 1378 (60) |

SD: standard deviation; HF: heart failure.

Department of Intensive Care Medicine consultation was carried out on 1064 occasions in the time window between 15:00 and 23:59 p.m. (47%), and took place in 1124 cases from the hospital emergency room (49%) and on the part of the physician on duty in 1117 cases (49%). The main reason for consultation was respiratory failure (n = 1080 [47%]), followed by altered level of consciousness (n = 911 [40%]) and hemodynamic instability (n = 741 [32%]). Assessment by the DICM in most cases was made by the specialist on duty (n = 1825 [81%]), with a professional experience of 6–15 years (n = 1040 [46%]). At the time of assessment, the mean APACHE II score was 20.38 (±8.52) with a mean SOFA score of 5.99 (±3.97). The mean Lee index was 12.73 (±4.07), while the mean Charlson score was 6.69 (±2.63).

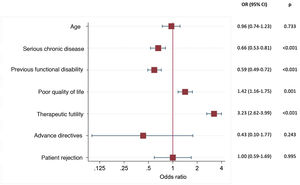

Reasons for deciding non-admission to the ICUThe decision to refuse admission to the ICU was made at initial assessment in almost all cases (n = 2127 [93%]). Estimated poor patient quality of life (n = 1417 [62%]), the presence of serious chronic illness (n = 1367 [60%]), and prior functional limitation of the patients (n = 1270 [56%]) were the main reasons underlying the decision to refuse admission as an LLST measure.

Variables related to the patient course following refusal of admission to the ICU:

Terminal sedation was started in 484 of the cases (21%) following the decision to refuse admission to the ICU.

The patient was informed of the decision in 368 cases (16%), while the family was informed in 1716 (75%). The decision was recorded in the patient case history in most cases (n = 2046 [90%]). Among the patients who were not informed of the decision to refuse admission to the ICU as an LLST measure (n = 1700 [81%]), the reason for consultation was altered level of consciousness in only 46% of the cases (n = 780).

Family disagreement with the decision was recorded in 54 cases (2%), while consulting physician disagreement was recorded in 138 cases (6%). In only 71 cases (3%) did posterior admission to the ICU take place once the decision had been made. Forty percent of these cases corresponded to patients with admission and care criteria as potential organ donors, while 18% corresponded to admissions decided as a consequence of external Department pressures.

The patient destination at hospital discharge was home in 65% of the cases, while in 20% of the cases the destination was a chronic care center.

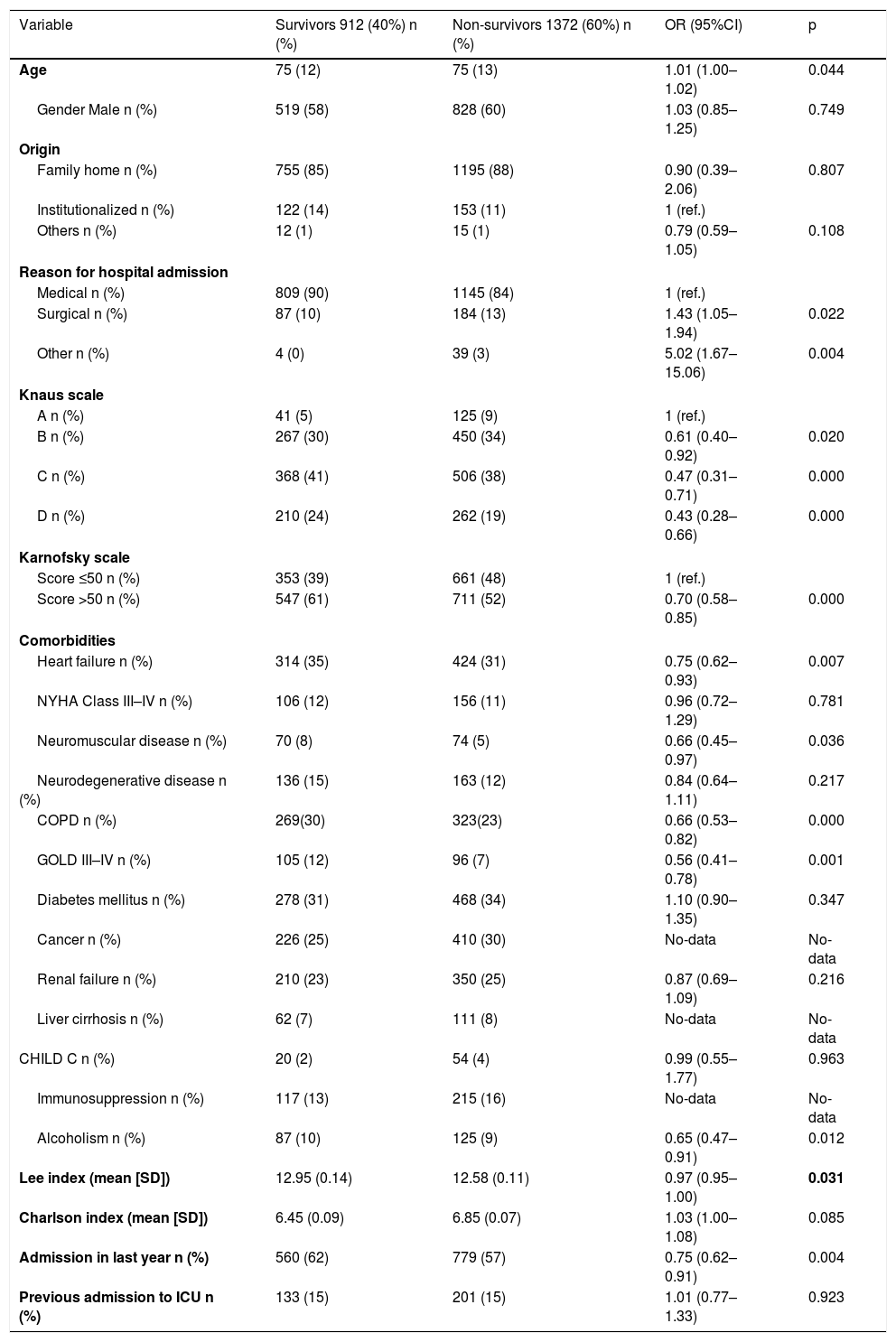

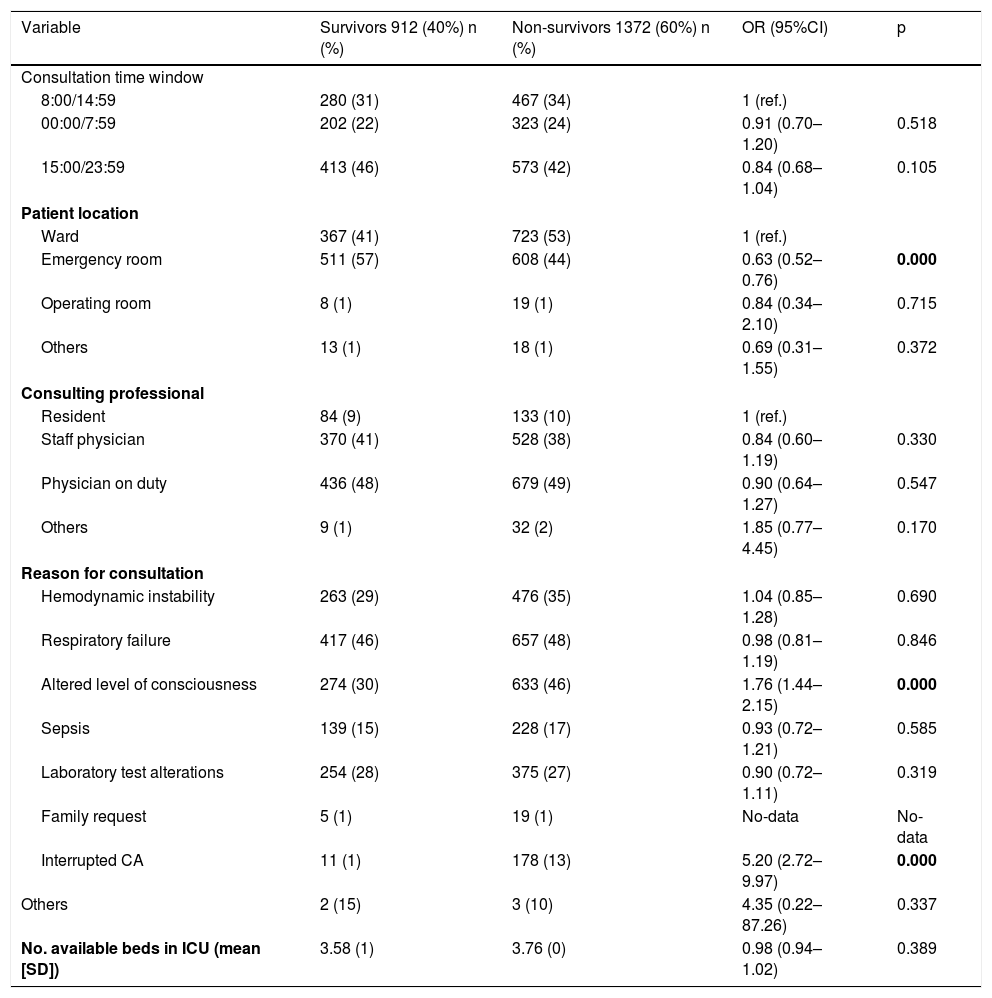

Mortality analysisFollowing the refusal of admission to the ICU as an LLST measure, the in-hospital mortality rate after 90 days in the study sample was 60.33%. The associations between the main clinical epidemiological parameters and mortality are reported in Table 3.

Differences in the characteristics of survivors and non-survivors in the study, and their association to mortality based on triple-level nested logistic regression analysis corrected for age and gender, and the APACHE II and SOFA scores.

| Variable | Survivors 912 (40%) n (%) | Non-survivors 1372 (60%) n (%) | OR (95%CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 75 (12) | 75 (13) | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.044 |

| Gender Male n (%) | 519 (58) | 828 (60) | 1.03 (0.85–1.25) | 0.749 |

| Origin | ||||

| Family home n (%) | 755 (85) | 1195 (88) | 0.90 (0.39–2.06) | 0.807 |

| Institutionalized n (%) | 122 (14) | 153 (11) | 1 (ref.) | |

| Others n (%) | 12 (1) | 15 (1) | 0.79 (0.59–1.05) | 0.108 |

| Reason for hospital admission | ||||

| Medical n (%) | 809 (90) | 1145 (84) | 1 (ref.) | |

| Surgical n (%) | 87 (10) | 184 (13) | 1.43 (1.05–1.94) | 0.022 |

| Other n (%) | 4 (0) | 39 (3) | 5.02 (1.67–15.06) | 0.004 |

| Knaus scale | ||||

| A n (%) | 41 (5) | 125 (9) | 1 (ref.) | |

| B n (%) | 267 (30) | 450 (34) | 0.61 (0.40–0.92) | 0.020 |

| C n (%) | 368 (41) | 506 (38) | 0.47 (0.31–0.71) | 0.000 |

| D n (%) | 210 (24) | 262 (19) | 0.43 (0.28–0.66) | 0.000 |

| Karnofsky scale | ||||

| Score ≤50 n (%) | 353 (39) | 661 (48) | 1 (ref.) | |

| Score >50 n (%) | 547 (61) | 711 (52) | 0.70 (0.58–0.85) | 0.000 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Heart failure n (%) | 314 (35) | 424 (31) | 0.75 (0.62–0.93) | 0.007 |

| NYHA Class III–IV n (%) | 106 (12) | 156 (11) | 0.96 (0.72–1.29) | 0.781 |

| Neuromuscular disease n (%) | 70 (8) | 74 (5) | 0.66 (0.45–0.97) | 0.036 |

| Neurodegenerative disease n (%) | 136 (15) | 163 (12) | 0.84 (0.64–1.11) | 0.217 |

| COPD n (%) | 269(30) | 323(23) | 0.66 (0.53–0.82) | 0.000 |

| GOLD III–IV n (%) | 105 (12) | 96 (7) | 0.56 (0.41–0.78) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus n (%) | 278 (31) | 468 (34) | 1.10 (0.90–1.35) | 0.347 |

| Cancer n (%) | 226 (25) | 410 (30) | No-data | No-data |

| Renal failure n (%) | 210 (23) | 350 (25) | 0.87 (0.69–1.09) | 0.216 |

| Liver cirrhosis n (%) | 62 (7) | 111 (8) | No-data | No-data |

| CHILD C n (%) | 20 (2) | 54 (4) | 0.99 (0.55–1.77) | 0.963 |

| Immunosuppression n (%) | 117 (13) | 215 (16) | No-data | No-data |

| Alcoholism n (%) | 87 (10) | 125 (9) | 0.65 (0.47–0.91) | 0.012 |

| Lee index (mean [SD]) | 12.95 (0.14) | 12.58 (0.11) | 0.97 (0.95–1.00) | 0.031 |

| Charlson index (mean [SD]) | 6.45 (0.09) | 6.85 (0.07) | 1.03 (1.00–1.08) | 0.085 |

| Admission in last year n (%) | 560 (62) | 779 (57) | 0.75 (0.62–0.91) | 0.004 |

| Previous admission to ICU n (%) | 133 (15) | 201 (15) | 1.01 (0.77–1.33) | 0.923 |

SD: standard deviation.

*Knaus scale: Class A: good previous health without functional limitations; Class B: mild/moderate limitation of activities due to chronic disease; Class C: severe but not disabling limitation due to chronic disease; Class D: severe restriction of activity due to disease.

**Hospital admission in the previous calendar year due to the disease causing current consultation of the Department of Intensive Care Medicine.

The assessment requests made from the emergency room were associated to lesser mortality (OR: 0.63; 95%CI: 0.52–0.76), taking as reference the consultations made from the conventional hospital wards. Apart from the cases of cardiac arrest in which the cessation of resuscitation was regarded as an LLST measure, consultation due to patient altered level of consciousness showed the strongest correlation to mortality (OR: 1.76; 95%CI: 1.44–2.15) (Table 4).

Associations between the variables related to consultation of the Department of Intensive Care Medicine and mortality based on multilevel nested logistic regression analysis corrected for age and gender, and the APACHE II and SOFA scores.

| Variable | Survivors 912 (40%) n (%) | Non-survivors 1372 (60%) n (%) | OR (95%CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consultation time window | ||||

| 8:00/14:59 | 280 (31) | 467 (34) | 1 (ref.) | |

| 00:00/7:59 | 202 (22) | 323 (24) | 0.91 (0.70–1.20) | 0.518 |

| 15:00/23:59 | 413 (46) | 573 (42) | 0.84 (0.68–1.04) | 0.105 |

| Patient location | ||||

| Ward | 367 (41) | 723 (53) | 1 (ref.) | |

| Emergency room | 511 (57) | 608 (44) | 0.63 (0.52–0.76) | 0.000 |

| Operating room | 8 (1) | 19 (1) | 0.84 (0.34–2.10) | 0.715 |

| Others | 13 (1) | 18 (1) | 0.69 (0.31–1.55) | 0.372 |

| Consulting professional | ||||

| Resident | 84 (9) | 133 (10) | 1 (ref.) | |

| Staff physician | 370 (41) | 528 (38) | 0.84 (0.60–1.19) | 0.330 |

| Physician on duty | 436 (48) | 679 (49) | 0.90 (0.64–1.27) | 0.547 |

| Others | 9 (1) | 32 (2) | 1.85 (0.77–4.45) | 0.170 |

| Reason for consultation | ||||

| Hemodynamic instability | 263 (29) | 476 (35) | 1.04 (0.85–1.28) | 0.690 |

| Respiratory failure | 417 (46) | 657 (48) | 0.98 (0.81–1.19) | 0.846 |

| Altered level of consciousness | 274 (30) | 633 (46) | 1.76 (1.44–2.15) | 0.000 |

| Sepsis | 139 (15) | 228 (17) | 0.93 (0.72–1.21) | 0.585 |

| Laboratory test alterations | 254 (28) | 375 (27) | 0.90 (0.72–1.11) | 0.319 |

| Family request | 5 (1) | 19 (1) | No-data | No-data |

| Interrupted CA | 11 (1) | 178 (13) | 5.20 (2.72–9.97) | 0.000 |

| Others | 2 (15) | 3 (10) | 4.35 (0.22–87.26) | 0.337 |

| No. available beds in ICU (mean [SD]) | 3.58 (1) | 3.76 (0) | 0.98 (0.94–1.02) | 0.389 |

SD: standard deviation.

Patient severity at the time of consultation, as assessed by the APACHE II and SOFA scores, was associated to an increase in mortality (OR: 1.07 [1.05–1.08], p = 0.000 and OR: 1.28 [1.24–1.33], p = 0.000, respectively) for each point of increase in score. As can be seen in Fig. 1, the futility of treatment was the reason for refusing admission to the ICU with the strongest correlation to in-hospital mortality (OR: 3.23; 95%CI: 2.62–3.99).

No differences in survival were observed on analyzing the physician performing the assessment in terms of either physical location (destination unit, Extended Intensive Care Service [EICS] or physician on duty) or years of experience.

The time elapsed between patient admission to hospital and assessment by the DICM was significantly longer among the patients who subsequently died (7.04 [0.54] versus 3.58 [0.67] days, p < 0.000; OR: 1.02 [1.01–1.03], p < 0.001).

DiscussionThe present study analyzes the decision to refuse admission to the ICU as an LLST measure, based on 2000 registries from 62 Spanish ICUs. It is the first study to adopt a systematic and exclusive approach in this field.

The results obtained highlight a low in-hospital mortality rate after 90 days (close to 60%) among those patients in which admission to the ICU was refused as an LLST measure. It is difficult to establish comparisons with other previous studies analyzing decisions against admission to the ICU in those patients considered to be too ill to benefit from admission, though the reported mortality rates range between 80%–100%.16–19 Despite our high survival rate, however, it cannot be discarded that these survivors were free of disabilities or showed progression of their functional limitation. In effect, up to 20% of the patients discharged from hospital were referred to chronic care centers.

On the other hand, our patients were older on average than the populations analyzed in other studies of similar characteristics,20–23 and only 7.4% had no limitations due to disease.

The results referred to the benefit of admitting or not admitting critically ill elderly patients to the ICU are discordant.24 Although our data show older age to be associated to increased in-hospital mortality following the refusal of admission, it has been postulated that frailty may be a more robust predictor of vulnerability and “recoverability” than chronological age in itself — particularly in the context of serious disease.25,26

The FRAIL-ICU study underscored the association between mortality and frailty in the critically ill. These patients were characterized by a greater percentage of LLST decisions in the ICU.27 This could suggest that lesser mortality in such frail subjects could be explained simply by the fact of avoiding those factors inherent to the intensive care setting that could worsen their prognosis.28

Likewise, and although there are no publications allowing for the comparison of results, we found the percentage of patients proposed for admission to the ICU from the emergency room to have significantly lower mortality than those patients proposed for admission to the ICU from the hospital ward. The fact that such patients came from the emergency room where first assessment was made, with possibilities for clinical improvement, could in part explain the observed low mortality.

Based on our results, the reasons of the intensivist for refusing admission to the ICU as an LLST measure were not significantly different from the LLST decisions described upon admission to the ICU in our setting. The main reasons were the presence of previous serious chronic illness, compliance with advance directives of the patient, prior functional limitation, and qualitative futility.29 Likewise, the INSTINCT study recently reported the impossibility of restoring autonomy, the presence of advanced stage chronic disease and poor quality of life to be the main reasons given for considering admission to the ICU as affording no benefit for the patient.30

Only 16% of the patients were informed about the decision. In this regard, it is true that critically ill patients are often characterized by circumstances that complicate or impede their full participation in the process.31 However, it must be considered that perceived quality of life among elderly ICU stay survivors (as in the case of our series of patients) is no different from that found in younger age groups, and moreover increases over time despite a decrease in activities of daily living.6

In three out of every four cases the decision was agreed with the patient relatives or representatives. However, studies have evidenced that the opinion of the relatives is not a reliable indicator of the wishes of the patient,32 and it has even been reported that the relatives may be unaware of the wishes of the patient in this respect.33 In any case, the level of agreement between the decision of the patient and that of the relatives in a hypothetical case is close to 70%.34 Likewise, the prognosis contemplated by the relatives is based not only on the information they receive from the medical team but also on other imponderable factors such as the robustness of the patient and his/her ability to overcome past diseases, as well as the impression gained from the physical appearance of the patient, etc.35

The present study has limitations. Firstly, the ICUs were not randomly selected but participated voluntarily in the study. Secondly, there are variable criteria among the professionals regarding the decision to admit a patient to the ICU. On the other hand, the 6-month study period might not be representative of the screening procedures over time in each ICU — giving rise to potential bias derived from the seasonal behavior of certain disease conditions. Nevertheless, we consider that the many participating Units and the total duration of the study adequately reflect daily practice in Spanish ICUs. In turn, some decisions might not have been duly recorded (weekends, holidays, etc.). Other possible sources of bias such as variable case registry, the absence of homogeneous protocols, the difference in proactive or upon-demand follow-up of the patients, and the different levels of implication of the hospitals may be considered to have been partially or fully resolved by the statistical analysis made.

It can be concluded that one of the main strengths of our study is the many decisions that have been recorded. This allows us to evidence that the decisions to limit admission to the ICU as an LLST measure are based on the same criteria as the decisions made within the ICU, and that in most cases refusal of admission does not lead to the death of the patients. This raises the hypothesis that the decisive factor in refusing admission was not the seriousness of the disease condition in itself but that the decision was influenced by the procedure and the comorbidities of the patient at the time of assessment. On the other hand, we wish to underscore the viability of the evaluations made by the intensivists in terms of therapeutic futility and the association to posterior mortality.

Author’s contributionsStudy conception and design, and data acquisition: Patricia Escudero Acha, Alejandro Gonzalez Castro.

Statistical analysis: Ines Gomez Acebo.

Data acquisition: Patricia Escudero Acha, Oihana Leizaola, Noelia Lázaro, Mónica Cordero, Ana María Cossío, Daniel Ballesteros, Paula Recena, Ana Isabel Tizón, Manuel Palomo, Maite Misis del Campo, Santiago Freita, Jorge Duerto, Naia Mas Bilbao, Barbara Vidal, Domingo González Romero, Francisco Diaz Dominguez, Jaume Revuelto, Maria Luisa Blasco, Monica Domezain, Mª de la Concepción Pavía Pesquera, Olga Rubio, Angel Estella, Angel Pobo, Alejandro González-Castro; ADENI Study Group.

Drafting of the manuscript or critical review of the intellectual content and final approval of the submitted version of the article: Alejandro Gonzalez Castro, Patricia Escudero Acha, Angel Estela, Angel Pobo, Olga Rubio.

Financial supportNone.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Escudero-Acha P, Leizaola O, Lázaro N, Cordero M, Cossío AM, Ballesteros D, et al. Estudio ADENI-UCI: Análisis de las decisiones de no ingreso en UCI como medida de limitación de los tratamientos de soporte vital. Med Intensiva. 2022;46:192–200.