To describe the needs of the families of patients admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and the opinion of ICU professionals on aspects related to the presence of patient relatives in the unit.

DesignA prospective descriptive study was carried out between March and June 2015.

SettingPolyvalent ICU of León University Healthcare Complex (Spain).

ParticipantsTwo samples of volunteers were studied: one comprising the relatives emotionally closest to the primarily non-surgical patients admitted to the Unit for over 48h, and the other composed of ICU professionals with over three months of experience in the ICU.

InterventionOne self-administered questionnaire was delivered to each relative and another to each professional.

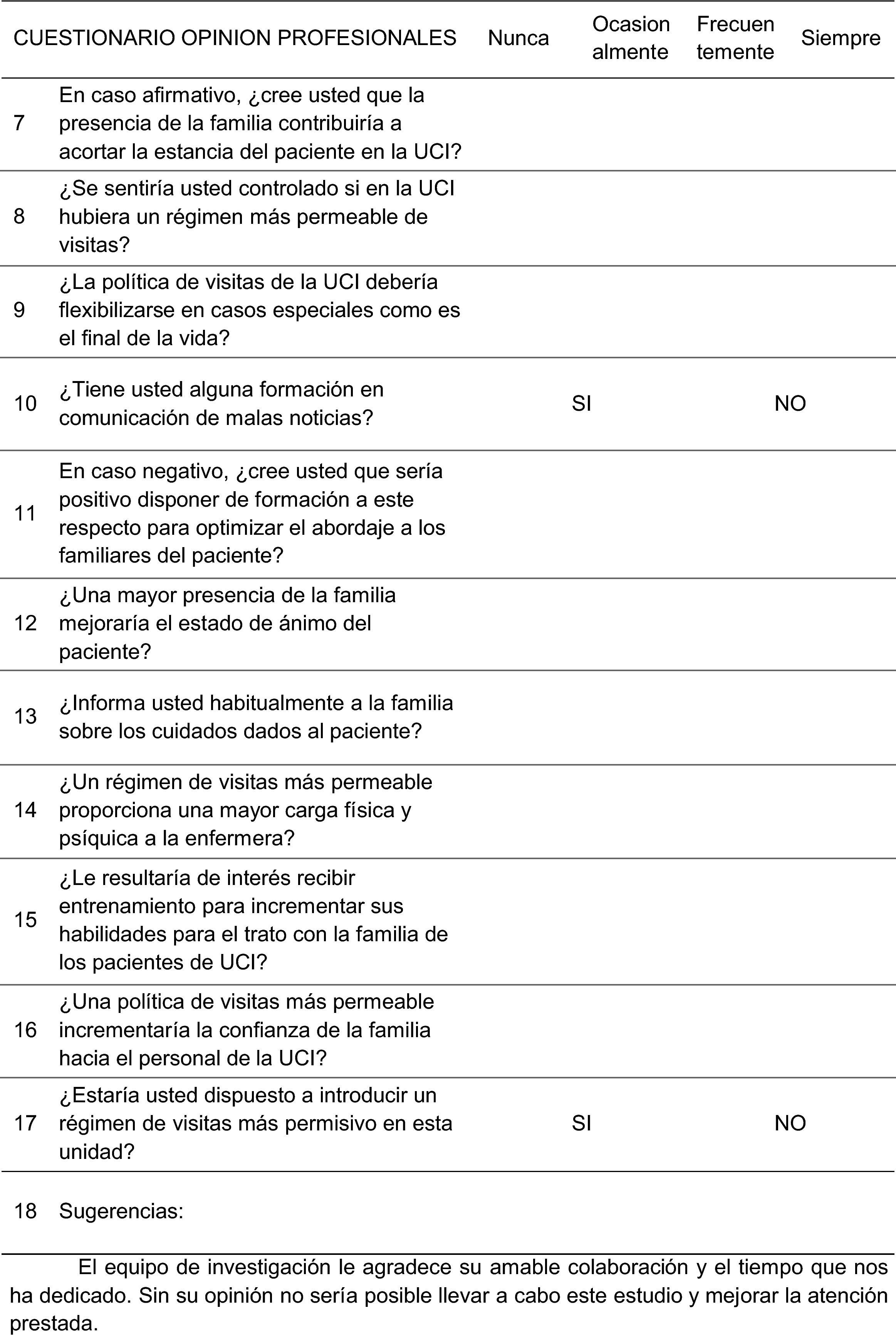

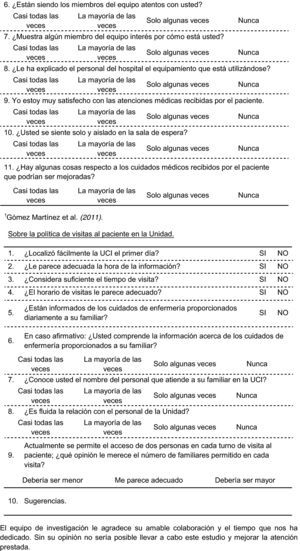

Main variables of interest: Sociodemographic data were collected. The variables in the questionnaire for relatives comprised the information received, closeness to the patient, safety of care, the support received, and comfort. In turn, the questionnaire for professionals addressed empathy and professional relationship with the family, visiting policy, and the effect of the family upon the patient.

ResultsA total of 59% of the relatives (35/61) answered the questionnaire. Of these subjects, 91.4% understood the information received, though 49.6% received no information on nursing care. A total of 82.9% agreed with the visiting policy applied (95.2% were patient offspring; p<0.05). Participation on the part of the professionals in turn reached 76.3% (61/80). A total of 59.3% would flexibilize the visiting policy, and 78.3% considered that the family afforded emotional support for the patient, with no destabilizing effect. On the other hand, 62.3% routinely informed the family, and 88% considered training in communication skills to be needed.

ConclusionsInformation was adequate, though insufficient in relation to nursing care. The professionals pointed to the need for training in communication skills.

Describir las necesidades de la familia del paciente ingresado en la UCI y la opinión de sus profesionales sobre aspectos relativos a la presencia familiar en la unidad.

DiseñoEstudio descriptivo prospectivo realizado entre marzo y junio de 2015.

ÁmbitoUCI polivalente del Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León.

ParticipantesDos muestras de voluntarios. Una compuesta por el familiar más próximo afectivamente a cada paciente ingresado en la unidad más de 48h, no primariamente quirúrgico. Otra de profesionales sanitarios con antigüedad superior a 3 meses en la UCI.

IntervenciónSe entregó un cuestionario autoadministrado a cada familiar y otro a cada profesional.

Variables de interés principales: se recogieron datos sociodemográficos. Las variables del cuestionario para familiares fueron: la información recibida, la proximidad al paciente, la seguridad en los cuidados, el apoyo recibido y la comodidad. La empatía y la relación profesional hacia la familia, la política de visitas y el efecto de la familia sobre el paciente fueron las variables del cuestionario para profesionales.

ResultadosParticipó el 59% de los familiares (35/61). El 91,4% comprendió la información recibida, aunque un 49,6% no recibió información sobre cuidados de enfermería. El 82,9% (95,2% eran hijos de pacientes, p<0,05) mostró conformidad con la política de visitas. La participación profesional fue del 76,3% (61/80). Un 59,3% flexibilizaría la política de visitas y para el 78,3% la familia apoya emocionalmente al paciente sin inestabilizarlo. Un 62,3% informaba habitualmente a la familia, estimando necesaria la formación en habilidades de comunicación un 88%.

ConclusionesLa información fue adecuada, resultando insuficiente en cuanto a los cuidados de enfermería. Los profesionales reclamaron formación en habilidades de comunicación.

The patient family setting comprises all those people related to the patient through affection, feelings or blood ties.1,2 In line with the ecological model of Bronfenbrenner,3 each member of the family experiences anxiety and concern in one form or other in the event of illness and hospital admission of a loved one.4,5 During this period, family life becomes disorganized, and each member experiences stress and anxiety,5,6 which in turn worsen when admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) proves necessary, because of the associated waiting and uncertainty, and the possibility of the death of the patient.7

Intensive Care Units in principle do not contemplate the presence of patient relatives in the Unit for prolonged periods of time.8 These Units are generally designed on a closed basis, and their environmental conditions, characterized by high technology, noise and artificial lighting, do not contribute to mitigate stress.2 These factors, associated to obligate separation between the patient and family imposed by the generally restrictive visiting regimens of these Units, further increase the impact for the family of experiencing the admission of a relative to intensive care.9–11

The literature underscores the need to offer professional care aimed at satisfying the needs of the family of the critical patient.1,4,9–13 In this regard, it is regarded as a priority concern for families to receive information in terms they can understand, with the provision of emotional and spiritual support. Furthermore, families should be able to perceive safety in the patient care environment, with access to the patient bedside, and should have comfortable facilities in which to spend the waiting period.1,4,6,11,13–17 However, the professional setting remains scantly sensitive to such needs,2,11,12 and is almost exclusively focused on patient care.16 The typical organizational model of these Units moreover complicates integration of the families, since the ICU is conceived as a work space, not as a scenario for interaction between professionals and users.12,18

A number of authors regard the family as a valuable tool for the integral management of the critical patient. On one hand, families contribute to lessen patient stress and delirium derived from the disease process and iatrogenic factors–with no complications being clearly attributable to the presence of the relatives at the patient bedside–and on the other hand they might contribute to shorten the stay of the patient in the ICU.2,14,19 Furthermore, the presence of a relative at the patient bedside improves communication and safety by allowing better understanding on the part of the professionals of certain patient expressions.9,20 In turn, the family has information that may exert a decisive influence upon the clinical outcome. The existing evidence therefore recommends family participation with the professional team in the deliberations referred to management of the patient.1,21,22

An analysis of the literature has only identified two studies that jointly address professional opinion and the perception of the relatives of the critical patient regarding the needs of the family17,23–despite the importance of combined consideration of the influence of the ICU setting and the professional and family points of view when conducting research in this field.

The aim of this study is to describe the needs of the families of patients admitted to the ICU and the opinion of the critical care professionals on aspects related to the presence of patient relatives in the Unit.

Patients and methodsStudy designA prospective correlational study was carried out between 1 March and 30 June 2015 in an adult polyvalent ICU.

Study contextThe Unit in this study has 16 individual closed boxes, a nurse/patient ratio of 1/2 and a nursing assistant/patient ratio of 1/4. There are two physicians on duty. This ICU does not cover patients in which the primary indication of admission is of a cardiological and/or surgical nature, since the hospital possesses a Coronary Unit and a resuscitation ward for surgical cases. However, the ICU does attend post-neurosurgery cases. The visiting policy contemplates two time intervals for visits by relatives: from 13:00h to 13:30h and from 19:00h to 19:30h, with access to the box of two relatives per patient. Medical information is provided upon admission and every 24h. Information referred to nursing care is left to the criterion of each professional. At the time of admission, a nursing assistant provides the family with a document explaining the norms of the Unit.

Study sampleDiscretional, non-probabilistic sampling was used to conform a study group of relatives of patients admitted to the ICU, and another group of healthcare professionals belonging to the Unit. The sample of relatives consisted of all the relatives of patients admitted during the study period and who met inclusion criteria consistent with those found in the literature6: age over 18 years; no mental or cognitive problems for answering the questionnaire; a primary cause of admission other than scheduled surgery; and an ICU stay of over 48h. Only one relative per patient was selected. The sample of healthcare professionals in turn consisted of all the physicians, nurses and nursing assistants working in the mentioned ICU during the study period and with at least three months of experience in the ICU as inclusion criterion.

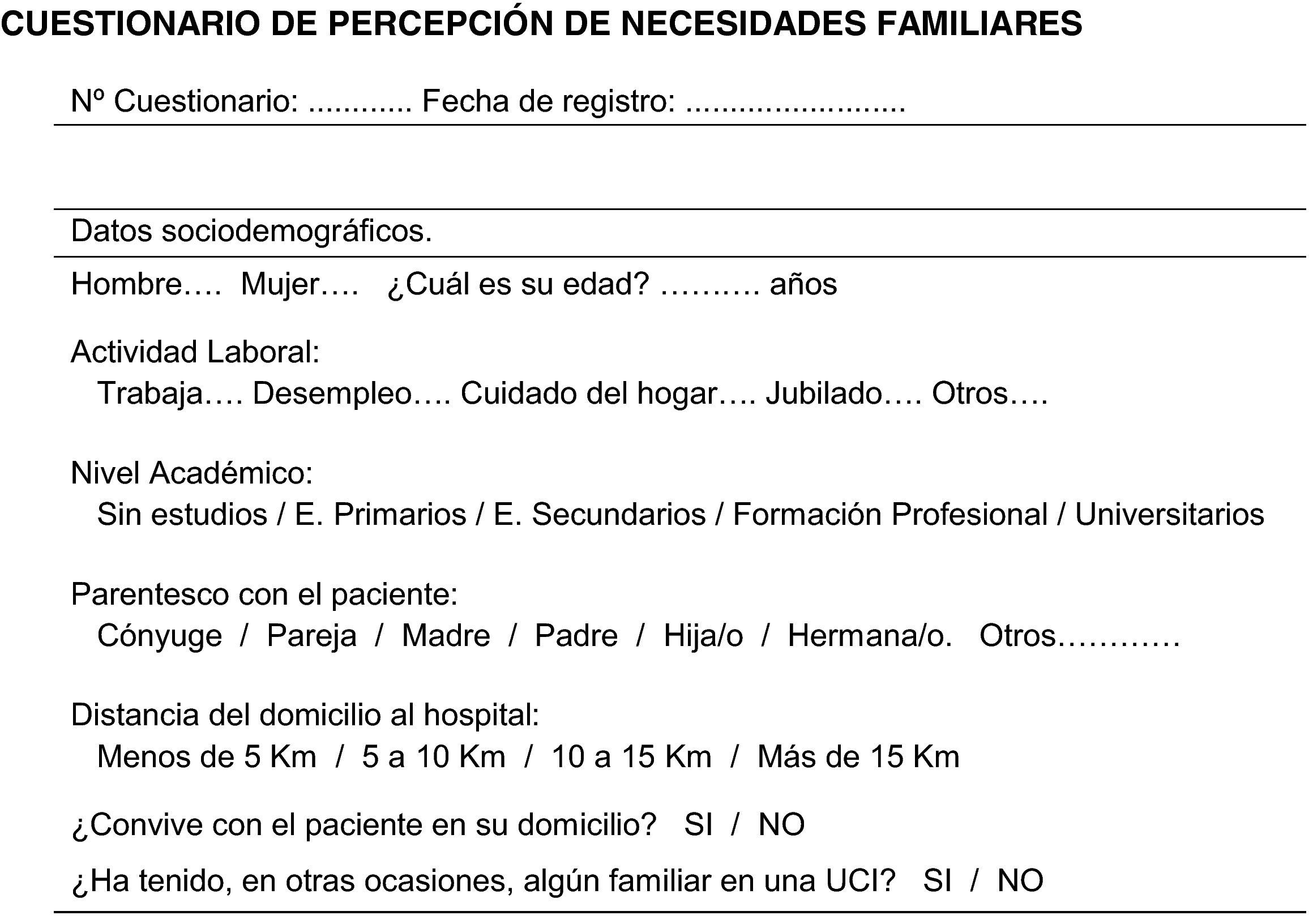

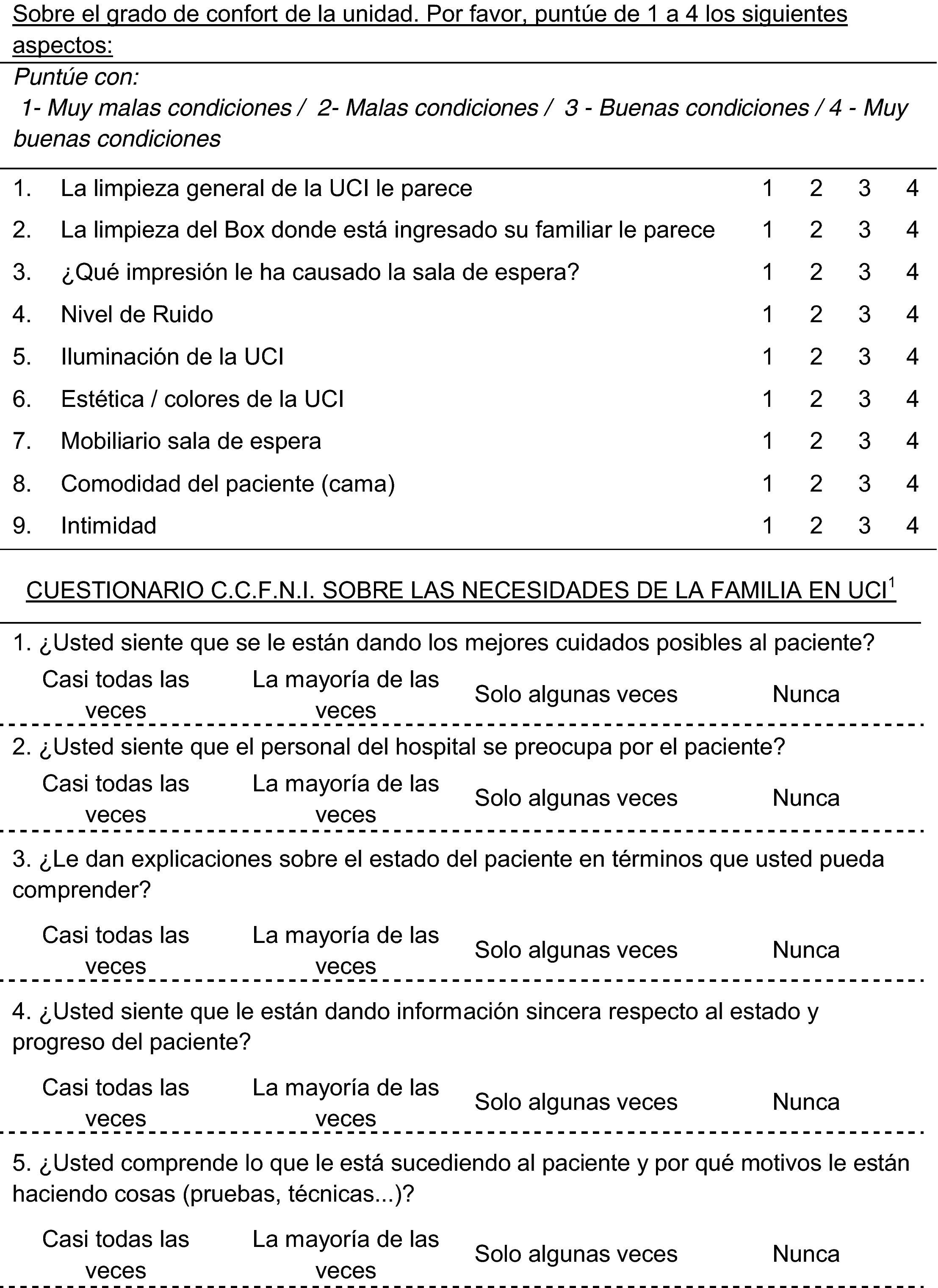

Study variablesThe following sociodemographic variables were recorded in the sample of relatives: age, gender, occupational activity, educational level, relation (kinship) to the patient, distance from home to hospital, cohabitation or non-cohabitation with the patient, and previous experiences of admission to the ICU. Each of the 5 factors referred to perceived family needs found in the literature were taken as dependent variables1,4,6,13–17: information received and its understanding, proximity to the patient, safety of the patient care environment, support received by the family, and comfort of the facilities.

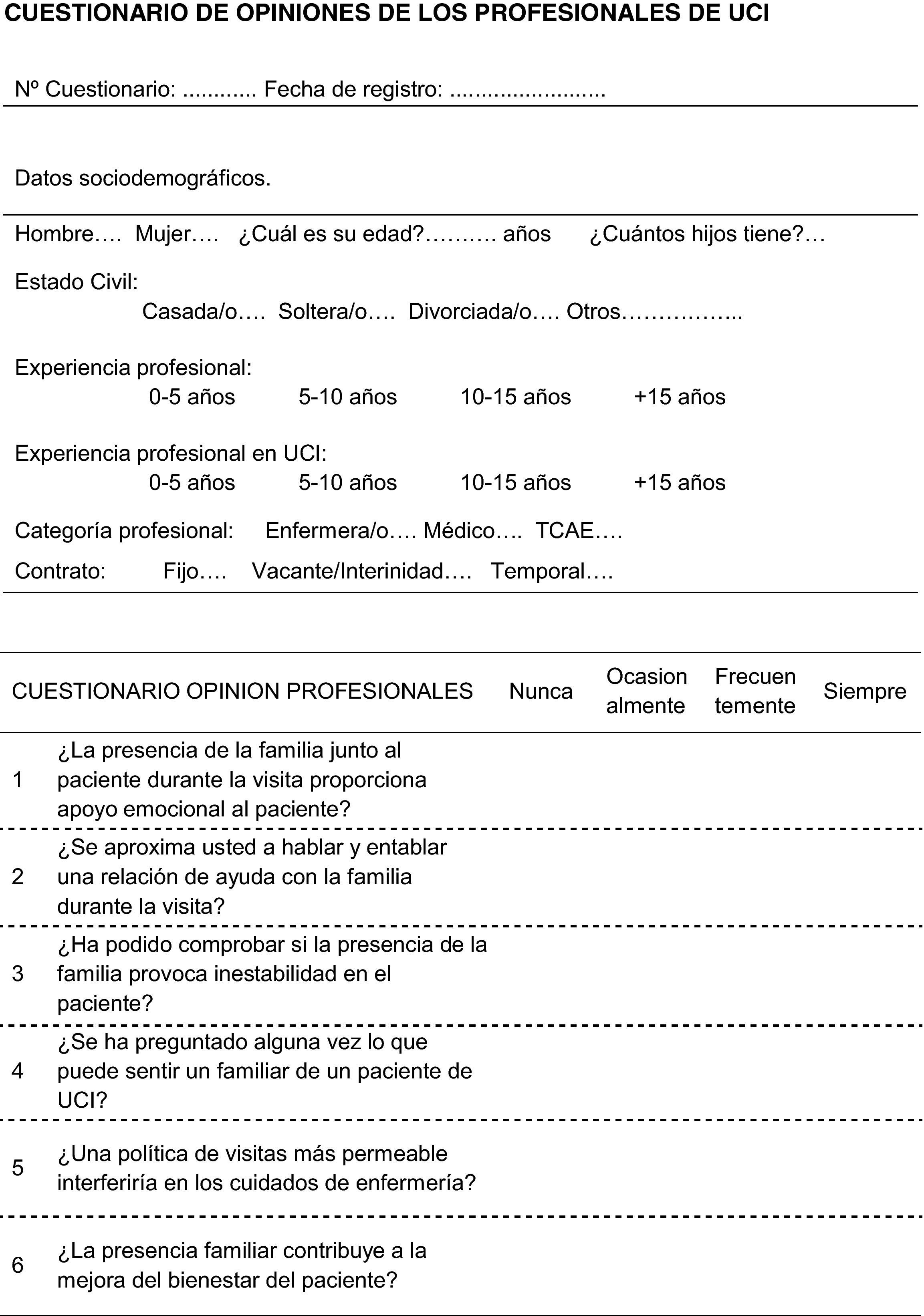

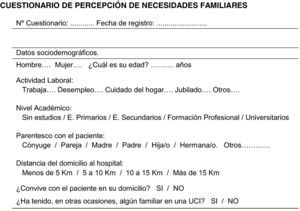

The study of the opinion of the professionals involved the documentation of sociodemographic variables: age, gender, marital status, number of offspring, profession, type of job contract, professional experience and experience in the ICU. The dependent variables in turn were defined as empathy of the professional toward the family, relationship of the professional with the family, rating of the visit as an added difficulty, opinion on open visiting policies, and opinion on the effect of the presence of relatives upon the patient.

InstrumentTwo self-administered questionnaires were used: one explored the perceptions of the relatives of patients admitted to the ICU (Annex 1), while the other evaluated the opinions of the professionals in the Unit (Annex 2). Each questionnaire was accompanied by instructions and an informed consent form guaranteeing confidentiality, the voluntary and anonymous nature of participation, and the possibility of withdrawing from the study at any time. In addition, the subjects were invited to know the results at the end of the study. During the daily visit, voluntary collaborators trained in the procedure and unrelated to the study group and ICU personnel provided each participant with a form to be delivered to the administrative office of the ICU.

The questionnaire for the relatives consisted of 29 items: 24 Likert-type multiple response items and 5 dichotomic response items, divided into two areas: one comprising the short version of the Critical Care Family Needs Inventory, validated for the Spanish population by Gomez et al.,24 with the obtainment of written permission from the authors for use of the instrument in our study; and another comprising a series of ad hoc questions based on the studies published by Pérez et al.,18 Santana et al.23 and Llamas et al.,6 with the purpose of exploring aspects not addressed by the available version of the Critical Care Family Needs Inventory.

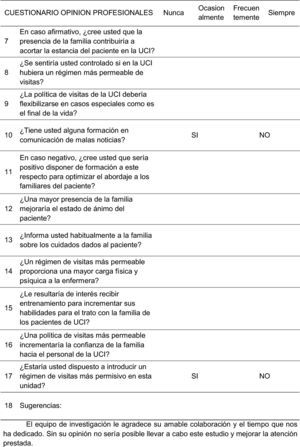

The consulted literature yielded no validated instruments for knowing the opinion of professionals referred to the subject of our study. We therefore developed an ad hoc questionnaire following the criteria of Marco et al.,25 Berti et al.26 and da Silva et al.10 in this respect. A form comprising 17 items was produced: 15 Likert-type multiple response items and two dichotomic response items. Both instruments also recorded sociodemographic information and contained an area for suggestions.

The validity of the contents of both instruments was ensured by adopting strict literature criteria in the course of their development, and subjecting both tools to analysis by a group of experts. Each questionnaire was validated for understanding based on two groups of volunteers, with incorporation of the observations to the final forms.

Statistical analysisThe Epi Info version 3.5.4 freeware package was used for the statistical analysis of the results. The Student t-test and chi-squared test were used, together with bivariate contrasting based on analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical significance was defined by a two-sided type I error probability of ≤5%, as assessed by a Pearson p-statistic of p≤0.05.

The present study was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee on 24 March 2015.

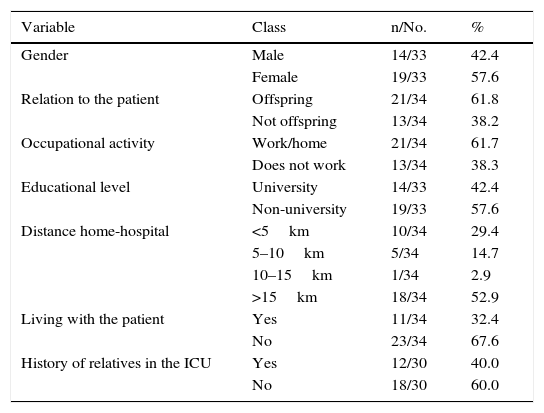

ResultsCharacteristics of the participantsA total of 61 questionnaires were distributed among the relatives of patients admitted to the ICU during the study period, with a response rate of 59% (35/61). The mean age of the relatives was 44.8±13.4 years. The predominant profile was that of a female, offspring of the patient, not living with the patient, and with a first experience with the ICU. Table 1 shows the demographic data corresponding to the relatives.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the families of the patients in the ICU.

| Variable | Class | n/No. | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 14/33 | 42.4 |

| Female | 19/33 | 57.6 | |

| Relation to the patient | Offspring | 21/34 | 61.8 |

| Not offspring | 13/34 | 38.2 | |

| Occupational activity | Work/home | 21/34 | 61.7 |

| Does not work | 13/34 | 38.3 | |

| Educational level | University | 14/33 | 42.4 |

| Non-university | 19/33 | 57.6 | |

| Distance home-hospital | <5km | 10/34 | 29.4 |

| 5–10km | 5/34 | 14.7 | |

| 10–15km | 1/34 | 2.9 | |

| >15km | 18/34 | 52.9 | |

| Living with the patient | Yes | 11/34 | 32.4 |

| No | 23/34 | 67.6 | |

| History of relatives in the ICU | Yes | 12/30 | 40.0 |

| No | 18/30 | 60.0 |

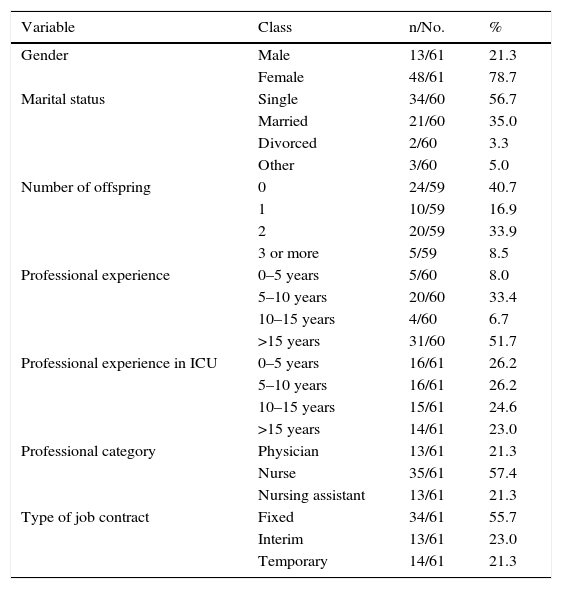

A total of 80 questionnaires were distributed among the healthcare professionals of the ICU, with a response rate of 76.3% (61/80). The mean age of the professionals was 42.8±9.4 years. The predominant profile was that of a female, nurse and with over 15 years of professional experience. Table 2 shows the demographic data corresponding to the healthcare professionals.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the healthcare professionals of the ICU.

| Variable | Class | n/No. | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 13/61 | 21.3 |

| Female | 48/61 | 78.7 | |

| Marital status | Single | 34/60 | 56.7 |

| Married | 21/60 | 35.0 | |

| Divorced | 2/60 | 3.3 | |

| Other | 3/60 | 5.0 | |

| Number of offspring | 0 | 24/59 | 40.7 |

| 1 | 10/59 | 16.9 | |

| 2 | 20/59 | 33.9 | |

| 3 or more | 5/59 | 8.5 | |

| Professional experience | 0–5 years | 5/60 | 8.0 |

| 5–10 years | 20/60 | 33.4 | |

| 10–15 years | 4/60 | 6.7 | |

| >15 years | 31/60 | 51.7 | |

| Professional experience in ICU | 0–5 years | 16/61 | 26.2 |

| 5–10 years | 16/61 | 26.2 | |

| 10–15 years | 15/61 | 24.6 | |

| >15 years | 14/61 | 23.0 | |

| Professional category | Physician | 13/61 | 21.3 |

| Nurse | 35/61 | 57.4 | |

| Nursing assistant | 13/61 | 21.3 | |

| Type of job contract | Fixed | 34/61 | 55.7 |

| Interim | 13/61 | 23.0 | |

| Temporary | 14/61 | 21.3 |

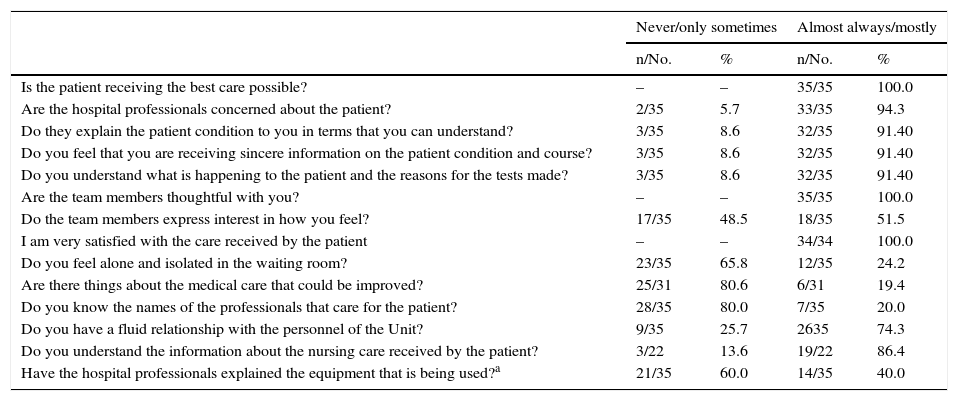

For the bivariate analysis, we stratified the perceptions of the relatives of the patients in the ICU according to the gender, occupational activity and educational level of the interviewed relative, as well as according to the patient relationship (kinship or no kinship), and cohabitation or non-cohabitation with the patient. The results are reported per the 5 needs identified in the consulted literature. Table 3 shows the results of family perception referred to the need for information and the support received, as well as the needs referred to the perception of safety in caring for the patient in the ICU.

Perceptions of the family (information, support and safety).

| Never/only sometimes | Almost always/mostly | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/No. | % | n/No. | % | |

| Is the patient receiving the best care possible? | – | – | 35/35 | 100.0 |

| Are the hospital professionals concerned about the patient? | 2/35 | 5.7 | 33/35 | 94.3 |

| Do they explain the patient condition to you in terms that you can understand? | 3/35 | 8.6 | 32/35 | 91.40 |

| Do you feel that you are receiving sincere information on the patient condition and course? | 3/35 | 8.6 | 32/35 | 91.40 |

| Do you understand what is happening to the patient and the reasons for the tests made? | 3/35 | 8.6 | 32/35 | 91.40 |

| Are the team members thoughtful with you? | – | – | 35/35 | 100.0 |

| Do the team members express interest in how you feel? | 17/35 | 48.5 | 18/35 | 51.5 |

| I am very satisfied with the care received by the patient | – | – | 34/34 | 100.0 |

| Do you feel alone and isolated in the waiting room? | 23/35 | 65.8 | 12/35 | 24.2 |

| Are there things about the medical care that could be improved? | 25/31 | 80.6 | 6/31 | 19.4 |

| Do you know the names of the professionals that care for the patient? | 28/35 | 80.0 | 7/35 | 20.0 |

| Do you have a fluid relationship with the personnel of the Unit? | 9/35 | 25.7 | 2635 | 74.3 |

| Do you understand the information about the nursing care received by the patient? | 3/22 | 13.6 | 19/22 | 86.4 |

| Have the hospital professionals explained the equipment that is being used?a | 21/35 | 60.0 | 14/35 | 40.0 |

| No | Yes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/No. | % | n/No. | % | |

| Are you informed about the nursing care received by the patient on a daily basis? | 17/35 | 48.6 | 18//35 | 51.4 |

Most of the relatives (91.4%) described the information received as comprehensible and sincere, and 51.4% reported having received daily information about the nursing care of the patient. In turn, 86.4% of the patients claimed to understand the information referred to such care. However, on stratifying such perception according to educational level, important differences were observed, since 71.4% of the university graduates versus 36.8% of the non-university graduates reported never or only sometimes having received daily information referred to nursing care–though statistical significance was not reached (p=0.051). In this same line, 60% of those interviewed reported never or only sometimes having received information on the equipment used in the ICU to attend the patient. This answer was more frequent among the university graduates (78.6%) than among the non-university graduates (42.1%) (p=0.03).

With regard to emotional support, the relatives unanimously agreed that the team members were attentive; 74.3% of those interviewed claimed to have a fluid relationship with the personnel, despite the fact that 80% did not know the name of the professional attending them. The relatives perceived safety in the patient care environment, rated patient care as the best care possible, and all of them claimed to be satisfied with the professional care received by the patient.

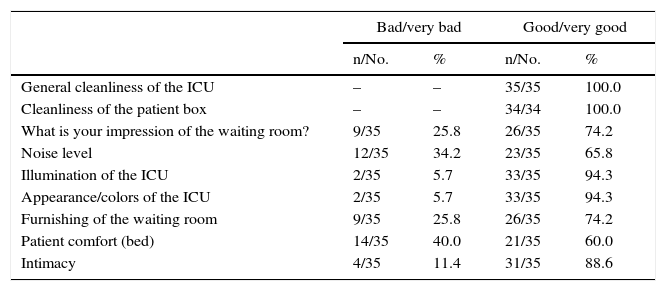

Table 4 shows the results referred to the need for closeness to the patient in the ICU, the Unit visiting policy, and the need for comfort referred to the facilities of the ICU. The relatives accepted the current visiting policy, including the number of relatives allowed to access the patient during the visit (88.6%), the duration of the visit (82.9%), and the visiting time intervals (85.7%). This latter perception was significantly more frequent among the offspring of the patients (95.2%; p=0.03). The conditions referred to cleanliness in the Unit were rated as good or very good (100%). The same rating was given by 94.3% of those interviewed in reference to the maintenance conditions of the facilities and illumination. Intimacy in the Unit was rated as good or very good by 88.6% of the relatives, and 74.2% gave the same rating to comfort and furnishing of the waiting room. Of note is the fact that 34.2% of the relatives described the sound conditions of the Unit as bad or very bad.

Perceptions of the family (visiting policy and comfort).

| Bad/very bad | Good/very good | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/No. | % | n/No. | % | |

| General cleanliness of the ICU | – | – | 35/35 | 100.0 |

| Cleanliness of the patient box | – | – | 34/34 | 100.0 |

| What is your impression of the waiting room? | 9/35 | 25.8 | 26/35 | 74.2 |

| Noise level | 12/35 | 34.2 | 23/35 | 65.8 |

| Illumination of the ICU | 2/35 | 5.7 | 33/35 | 94.3 |

| Appearance/colors of the ICU | 2/35 | 5.7 | 33/35 | 94.3 |

| Furnishing of the waiting room | 9/35 | 25.8 | 26/35 | 74.2 |

| Patient comfort (bed) | 14/35 | 40.0 | 21/35 | 60.0 |

| Intimacy | 4/35 | 11.4 | 31/35 | 88.6 |

| No | Yes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/No. | % | n/No. | % | |

| Did you easily find the ICU the first day? | 12/34 | 35.3 | 22/34 | 64.7 |

| Was the timing of information adequate? | 4/35 | 11.4 | 31/35 | 88.6 |

| Was the visiting time sufficient? | 6/35 | 17.1 | 29/35 | 82.9 |

| Was the timing of visits adequate?a | 5/35 | 14.3 | 30/35 | 85.7 |

| Not adequate | Adequate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/No. | % | n/No. | % | |

| What do you think about the number of relatives allowed? | 4/35 | 11.4 | 31/35 | 88.6 |

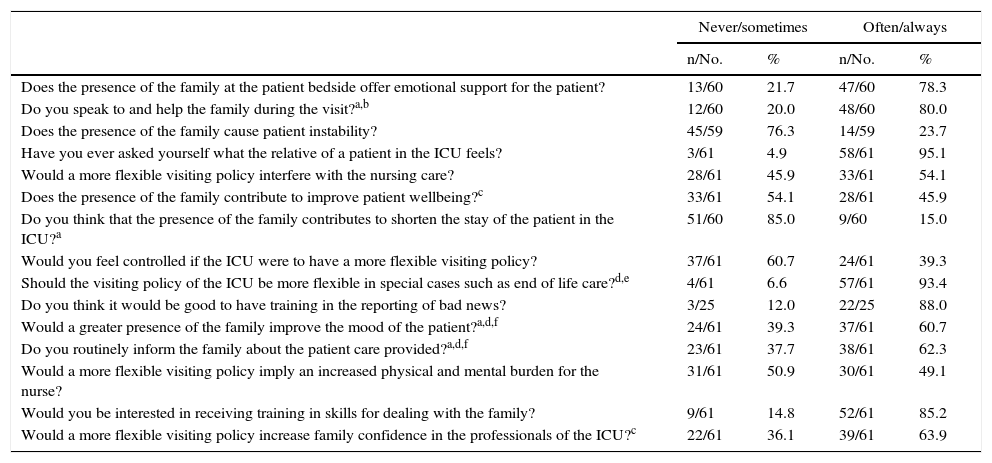

The opinions of the professionals in our ICU were stratified per gender, professional category, type of contract and experience in the ICU. Table 5 describes the results of the healthcare professionals regarding aspects associated to the family of the patient.

Opinions of the professionals of the ICU.

| Never/sometimes | Often/always | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/No. | % | n/No. | % | |

| Does the presence of the family at the patient bedside offer emotional support for the patient? | 13/60 | 21.7 | 47/60 | 78.3 |

| Do you speak to and help the family during the visit?a,b | 12/60 | 20.0 | 48/60 | 80.0 |

| Does the presence of the family cause patient instability? | 45/59 | 76.3 | 14/59 | 23.7 |

| Have you ever asked yourself what the relative of a patient in the ICU feels? | 3/61 | 4.9 | 58/61 | 95.1 |

| Would a more flexible visiting policy interfere with the nursing care? | 28/61 | 45.9 | 33/61 | 54.1 |

| Does the presence of the family contribute to improve patient wellbeing?c | 33/61 | 54.1 | 28/61 | 45.9 |

| Do you think that the presence of the family contributes to shorten the stay of the patient in the ICU?a | 51/60 | 85.0 | 9/60 | 15.0 |

| Would you feel controlled if the ICU were to have a more flexible visiting policy? | 37/61 | 60.7 | 24/61 | 39.3 |

| Should the visiting policy of the ICU be more flexible in special cases such as end of life care?d,e | 4/61 | 6.6 | 57/61 | 93.4 |

| Do you think it would be good to have training in the reporting of bad news? | 3/25 | 12.0 | 22/25 | 88.0 |

| Would a greater presence of the family improve the mood of the patient?a,d,f | 24/61 | 39.3 | 37/61 | 60.7 |

| Do you routinely inform the family about the patient care provided?a,d,f | 23/61 | 37.7 | 38/61 | 62.3 |

| Would a more flexible visiting policy imply an increased physical and mental burden for the nurse? | 31/61 | 50.9 | 30/61 | 49.1 |

| Would you be interested in receiving training in skills for dealing with the family? | 9/61 | 14.8 | 52/61 | 85.2 |

| Would a more flexible visiting policy increase family confidence in the professionals of the ICU?c | 22/61 | 36.1 | 39/61 | 63.9 |

| No | Yes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/No. | % | n/No. | % | |

| Do you have any training in the reporting of bad news?b | 26/61 | 42.6 | 35/61 | 57.4 |

| Would you be willing to accept a more flexible visiting regimen in the Unit? | 24/59 | 40.7 | 35/59 | 59.3 |

A total of 95.1% of the professionals claimed to have experienced empathy with the feelings of the relatives of patients admitted to the Unit. Eighty percent routinely established a relationship characterized by help for the family of the patient – the frequency being significantly higher among males than females (100% versus 74.5%, respectively; p=0.04), as well as among professionals with over 15 years of experience in the Unit than in those with less than 5 years of experience (85.7% versus 52.3%, respectively; p=0.01). In turn, 62.3% of the professionals claimed to routinely inform the family about patient care. Significant differences (p=0.0001) were recorded in this respect according to professional category: 100% of the physicians, 62.9% of the nurses and 23.1% of the nursing assistants claimed to offer information on a regular basis. There were also significant differences (p=0.01) in the provision of information according to gender and the type of job contract: males provided information more often than females (92.3% versus 54.2%, respectively), and fixed personnel provided information more often than interim personnel (28.6%).

A total of 57.4% of the professionals (83.3% males and 52.1% females) claimed to have training in reporting bad news, with significant differences (p=0.01) according to professional category: 92.3% were physicians, 52.9% were nurses, and 38.5% nursing assistants. In turn, 85.2% of the professionals reported interest in receiving training of this kind.

Over one-half of the professionals (63.9%) considered that increased flexibility of the visiting policy would improve family confidence in the professionals of the ICU. This opinion was significantly more prevalent (p=0.01) among professionals with fixed (73.5%) and interim contracts (71.4%) than among professionals with temporary contracts (30.8%). There was also a significantly more prevalent opinion (p=0.02) in favor of a more flexible visiting policy in exceptional situations, such as end of life care, among the professionals with fixed (97.1%) and interim contracts (100%). According to professional category, this opinion was expressed by 97.1% of the nurses, 100% of the nursing assistants and 76.9% of the physicians (p=0.02).

A total of 78.3% of the interviewed professionals considered that the presence of the family affords emotional support for the patient. Regarding the possible improvement in patient mood state as a result of the presence of the family, we recorded significant differences according to gender and type of job contract (p=0.01), as well as according to professional category (p=0.001). By gender, 92.3% of the males and 54.2% of the females were of this opinion, in the same way as 73.5% of the fixed personnel and 28.6% of the interim personnel, and 100% of the physicians, 62.9% of the nurses and the 23.1% of the nursing assistants. The opinion that the family might contribute to patient wellbeing was significantly more often expressed (p=0.001) by males (84.6%) than females (35.6%). There were also significant gender differences (p<0.05) referred to the possible influence of the family in shortening patient stay in the ICU–females expressing disagreement with this idea more often than males (89.6% versus 66.7%, respectively).

DiscussionThe present study relates the perceptions of the families of the patients admitted to our ICU to the opinions of the professionals, in a way analogous to the study published by Santana et al.23 The participation rate among the professionals was similar to that of the mentioned study, with a somewhat lower participation on the part of the relatives of the patients. The methodological design of the study and the admission dynamics inherent to Units of this kind during the study period conditioned the sample size of this group. However, by selecting a single relative per patient (the relative affectively closest to the patient), we believe that data duplication bias was avoided. Likewise, and in line with the methodology of Llamas et al.,6 the anonymous nature of the questionnaires avoided bias associated to direct questioning by an interviewer.

The evidence found in the literature points to comprehensible and true information from the professional as the most important need for the family of the patient.1,4–9,11,15,23 Our results reflect a positive opinion of the family regarding the information supplied on the condition of the patient, the care strategy and treatment offered. The relatives rated such information as sincere, comprehensible and adequate in terms of the time interval in which it is provided – this being consistent with other studies6,23 and with the recommendations of the reviews1,21 and international clinical practice guides.27,28 However, the results obtained underscore an increased demand for information on the part of relatives with a university education, confirming the tendency found in the literature7 toward a progressive and individualized demand for information, in contrast to the promptness and simplicity characterizing the traditional paternalistic approaches in this respect. In addition, our results, in line with those of Pérez et al.,18 indicate a low proportion of relatives who claim to have received information on nursing care and the equipment used for patient care. Nevertheless, those interviewed considered such information (when provided) to be easy to understand, in coincidence with the observations of Llamas et al.6

It is therefore clear that the family need for information is not fully satisfied in our setting. A quantitative, though not qualitative, defect is observed in the information received from the nursing personnel in our ICU. The results indicate that all the physicians informed the families, compared with only two-thirds of the nurses. The informative model of this ICU could be one of the factors underlying this information defect.

Nurses traditionally tend to provide limited information in the belief that this function is exclusive of the medical personnel.18 In relation to this idea, Zaforteza et al.12 have reported that imbalances in power relations among members arise within multidisciplinary teams, leading to asymmetries and the cession, restriction or prevalence of attributes and criteria among professionals. These circumstances could lie at the root of the observed nursing information deficiencies. Furthermore, they could explain why the nurses with the greatest experience and occupational stability within the ICU were those who more often claimed to offer information and establish a helping relationship with the relatives.

In line with the observations of some authors,7 we consider that a model based on the complementary distribution of information tasks among the professionals is the best option for offering global information to the family of the patient. According to this model, the nursing personnel would supply information on patient care, rest, comfort and mood state, as well as on the technological equipment used and the reasons for certain types of care, while information referred to the clinical diagnosis, management strategies and prognosis would clearly be the responsibility of the medical personnel.4,7 On the other hand, fluid communication within the team is essential in order to improve patient safety and optimize the clinical outcomes.12

Of note is the observation that most of the professionals with training in reporting bad news were physicians. However, in line with the consulted literature,4 the great majority of the interviewed professionals considered it advisable to have such training as a means to satisfy the family need for information. We coincide with Escudero et al.4 in the need to receive adequate communication training, and in the same way as Pérez et al.18 encourage nursing professionals to pursue the necessary change in mentality in order to satisfactorily inform the family about the nursing care received by the patient.

As evidenced by the literature, family access to the patient bedside becomes more important when the loved one is admitted to intensive care.1,8,9,11 Our visiting policy follows a closed standard, as defined by Giannini.29 The results obtained show the relatives to accept this policy, and in coincidence with Pérez et al.,18 we consider that the desire of the family to allow the patient to rest might be the cause of such acceptance. However, we agree with many authors that respect of the rights of the patients and their families, as well as improved satisfaction of their needs, require the adoption of open-door visiting policies in the ICU. In this regard, such open policies have been shown to reduce stress and anxiety among the patients and families, and increase confidence in the healthcare professional – in concordance with some of our own results.1,4,6,7,9,10,18,23,30,31

The interviewed professionals were predominantly in favor of greater flexibility of the current visiting policy. Many studies consider that adequate visiting policies suited to each Unit should arise from professional consensus based on the recommendations of the guides centered on patient and family care. Such visiting policies inevitably cannot be associated to any institutional or corporate criterion, and must seek to respect the rights of the patients and their families as a fundamental concern.2,7,9,10,12,18,32

Our results evidence duality in professional opinion about the possible effect of the presence of the family at the patient bedside. On one hand, such a presence is seen as a source of support, wellbeing and improved mood state for the patient, though on the other hand it is considered to generate an increased physical and psychological burden, as well as a feeling of control over the professionals that would interfere with patient care. In our opinion, and despite the evidence of the benefits of family presence at the patient bedside,1,4,7,9,11,20,29 this duality introduces a factor of uncertainty blocking any attempt to advance in flexible visiting policies designed to satisfy the needs of the family.

The interviewed families considered professional attention to be friendly and fluid, in line with the findings of Santana et al.23 However, they reported little personnel implication toward them, and often did not know the name of attending professional. The literature indicates that family perception of support is directly related to the visiting policy and empathy on the part of the professionals. In this regard, the lack of a reference professional tends to be a source of stress and anxiety for the family. In these situations, the family itself, and other families of other patients, become an informal source of support that offsets the lack of formal support.6,32 We agree with Pardavila and Vivar7 in the need to introduce a formal support network based on synergies with social workers, psychologists and religious counseling services, in order to satisfy the needs of those families or patients that require such support.

On the other hand, our results suggest adequate attention to the family need to perceive a safe patient care environment, in line with the observations of the literature that regard this as one of the most important issues.1,7,15–17 The environmental and hygiene conditions of the Unit were almost unanimously rated as adequate. However, and in coincidence with Escudero et al.,11 environmental noise is seen to remain a problem in many ICUs.

As limitations of the study, mention must be made of the limited sample size, the lack of validation of the questionnaire for the professionals, and of part of the questionnaire for the families, as well as the fact that data collection took place while the patient was still in the ICU. All this precludes the extrapolation of our results beyond the context of this study. Nevertheless, the findings are consistent with the available evidence,1,4,6,7,9–11,15–18,21,23,30,31 which confers internal validity of the data obtained.

Further efforts are required in this line of research, adopting qualitative and quantitative approaches to develop homogeneous methodologies and adequately validated measurement instruments allowing the extrapolation of results and continued progress in care centered on the patients and their families.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors thank the Nursing Management and the Department of Intensive Care Medicine of the CAULE, as well as the Department of Nursing and Physiotherapy of the University of León for the facilities and support received in relation to the present study. Thanks are also due to the professionals of the ICU of the CAULE for their collaboration, and to the families of the patients who volunteered to participate in the study.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez-Vallejo A, Fernández D, Pérez-Gutiérrez A, Fernández-Fernández M. Análisis de las necesidades de la familia del paciente crítico y la opinión de los profesionales de la unidad de cuidados intensivos. Med Intensiva. 2016;40:527–540.