The arrhythmic storm due to sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (SMVT) is a life-threatening condition in which the catheter ablation procedure is key for management purposes, especially in the presence of a scar.1,2 Similarly, it is advisable to look for the presence of coronary ischemia and proceed to correct it.2 Yet none of these procedures is risk-free, especially in the presence of hemodynamic instability or severe ventricular dysfunction. In this paper we will see an example of the utility of ECMO in this clinical scenario.

A seventy-year-old male was admitted to our center ER after receiving three (3) discharges from his automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator (AICD). He had a prior history of diabetes and arterial hypertension. Also, ten (10) years ago he suffered from an episode of SMVT with a left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) of 30%, chronic occlusion of his right and circumflex coronary arteries with lack of viability in such territories based on the single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scan, which is why an AICD was implanted followed by amiodarone.

The patient was admitted to the Acute Cardiology Care Unit, his AICD checked, and then it was confirmed that the discharges had been appropriate following an episode of SMVT. While the patient was being monitored, common self-limiting episodes of such arrhythmias were seen, which is why treatment with procainamide in perfusion was prescribed and the AICD therapies disconnected.

This time, the echocardiogram showed a LVEF of 25% and the coronariography showed one severe de novo lesion in the proximal anterior descending artery. After heart-team discussion of the case, it was decided to revascularize the anterior descending artery and perform the ablation of the SMVT. Both were high-risk procedures, which is why hemodynamic support with venoarterial ECMO was taken into consideration.

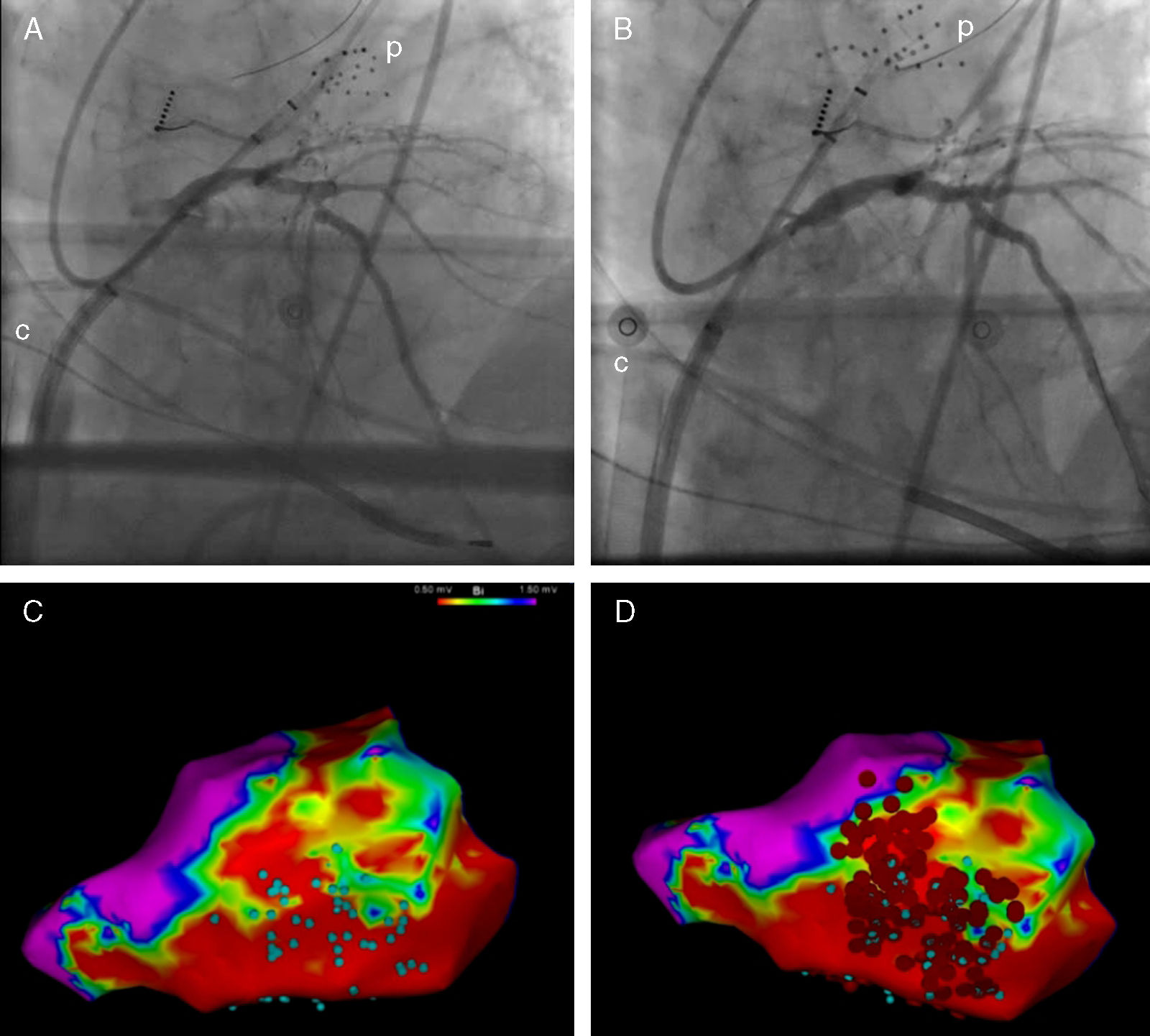

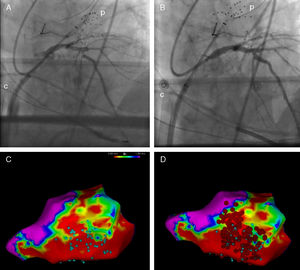

The intervention was conducted at the electrophysiology lab with intubation, sedation with Propofol, analgesia with remifentanil and cisatracurium for muscle relaxation. In the first place, the left ventricle was accessed using the transseptal puncture technique; then one IV bolus dose of heparin was administered with ECMO support percutaneous implantation through the femoral approach. The Cardiohelp® device was used (Maquet, Germany), with a 15F arterial cannula and a 23F venous cannula. The ECMO support was initiated with 1.5bpm and with the possibility of increasing flow if necessary. The next step was to treat the stenosis of the anterior descending artery by implanting one drug-eluting stent (Fig. 1A and B). During this revascularization, the arterial blood pressure dropped and pulsatility disappeared, which is why the ECMO flow was brought to 3bpm in order to keep the average blood pressure above 60mmHg. This situation was maintained for another 15min due to myocardial stunning, after which pulsatility slowly recovered. And that is when the ablation started. Endocardial voltage mapping during sinus rhythm was created using one multidetector-row catheter with the CARTO® 3 system (Biosense Webster Inc., USA); 1.5 and 0.5mV were the voltage limits used to define scar and dense scar. Also, inside the scar, electrogram areas with isolated or potentially delayed components (Fig. 1C) were identified. During the scheduled pacing no SMVTs were induced, but ventricular fibrillation was induced that had to be terminated through defibrillation. Once again, we saw that after the shock a period of several minutes of hypotension and loss of pulsatility followed, during which the ECMO support was increased. Finally, one arrhythmic substrate extensive ablation procedure was conducted (Fig. 1D).

Pre- (A) and postoperative coronary intervention fluoroscopy (B). Endocardial voltage mapping showing inferior–lateral scar. Electrogram areas with isolated or potentially delayed components (C, blue dots) and ablation sites (D, red dots). c: ECMO venous cannula; p: electrophysiology mapping and imaging catheter.

After finishing the procedure, the patient remained hemodynamically stable and with a good pulse amplitude, which is why it was decided to remove the circulatory support system. The decannulation was conducted in the lab by the vascular surgeon with vein and femoral artery repair. The patient's progression was favorable without SMVT recurrences, and he was discharged from the hospital five (5) days after the procedure.

The case presented here shows the benefits that circulatory support can provide in the management of arrhythmic storms. This support can be necessary in cases of incessant forms of arrhythmia and hemodynamic instability, and also as the back-up of high-risk therapeutic interventions. In particular, the patient described above had a high-risk coronary anatomy with a significant lesion in his only patent blood vessel, which elevated the risk of the revascularization and the ablation procedure.

Today, there are several hemodynamic support devices available to conduct high-risk percutaneous procedures: counter-pulsation balloon, TandemHeart®, Impella®, venoarterial ECMO.3 Of all, the ECMO support guarantees a full circulatory support and a minimum interference when manipulating the catheters. There is prior experience using ECMO support in percutaneous revascularization procedures, in the implantation of percutaneous valves, and in the ablation of arrhythmias,3–6 and it has also been used for the hemodynamic rescue of arrhythmic storms.6,7 On the other hand, ECMO implantation, initially surgical, has evolved toward percutaneous cannulation, making it a useful tool fully available for all hemodynamic and electrophysiology labs.8,9

Our case illustrates the possibilities of ECMO in the circulatory support of percutaneous devices. Also, it has the peculiarity of being the first case ever reported in medical literature where two (2) consecutive procedures (coronary revascularization and ablation) were conducted with short-term support with the advantage of reducing health care time and avoiding second cannulations.

Please cite this article as: Sousa-Casasnovas I, Ávila-Alonso P, Juárez-Fernández M, Díez-Delhoyo F, Martínez-Sellés M, Fernández-Avilés F. Tormenta arrítmica resuelta tras angioplastia y ablación bajo soporte con oxigenación de membrana extracorpórea venoarterial. Med Intensiva. 2018;42:504–506.