The current COVID-19 pandemic has rendered up to 15% of patients under mechanical ventilation. Because the subsequent tracheotomy is a frequent procedure, the three societies mostly involved (SEMICYUC, SEDAR and SEORL-CCC) have setup a consensus paper that offers an overview about indications and contraindications of tracheotomy, be it by puncture or open, clarifying its respective advantages and enumerating the ideal conditions under which they should be performed, as well as the necessary steps. Regular and emergency situations are displayed together with the postoperative measures.

La alta incidencia de insuficiencia respiratoria aguda en el contexto de la pandemia por COVID-19 ha conllevado el uso de ventilación mecánica hasta en un 15%. Dado que la traqueotomía es un procedimiento quirúrgico frecuente, este documento de consenso, elaborado por tres Sociedades Científicas, la SEMICYUC, la SEDAR y la SEORL-CCC, tiene como objetivo ofrecer una revisión de las indicaciones y contraindicaciones de traqueotomía, ya sea por punción o abierta, esclarecer las posibles ventajas y exponer las condiciones ideales en que deben realizarse y los pasos que considerar en su ejecución. Se abordan situaciones regladas y urgentes, así como los cuidados posoperatorios.

Tracheotomy is a frequent procedure in Intensive Care Units (ICUs) among patients with respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation (MV).1

In the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, COVID-19 disease in its most severe form manifests as acute respiratory failure that can progress towards acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which in many cases requires the use of MV. According to the different series, between 9.8 and 15.2% of such patients require MV.2–4 Surgical tracheotomy is the most common surgical procedure among critical patients with COVID-19.5

The mortality rate among patients with COVID-19 subjected to MV is high, and can reach 50%.6 These patients need ventilation strategies initially requiring deep sedoanalgesia and even relaxation, protective ventilation, recruitment maneuvering and prone decubitus.7 All this implies that many patients will be on MV for days, with a high risk of developing muscle weakness acquired in the ICU - a situation that complicates weaning from ventilation. The use of specific antiviral drugs can result in interactions with sedatives and analgesics, prolonging their effects.8 The appearance of delirium, which is common in these patients, can also condition successful weaning from MV.

Infection due to SARS-CoV-2 has shown great transmissibility, particularly via the respiratory route and through the dispersion of droplets. Specific recommendations have been made regarding the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and airway management related to intubation and MV. Procedures that generate aerosols pose a high risk of contagion, especially intubation, fiberoptic bronchoscopy and tracheotomy.9

A number of technical recommendations have been made for performing tracheotomy in patients with COVID-19, though there is not enough evidence on certain aspects such as the optimum time for performing the procedure, the type of procedure (surgical versus percutaneous tracheotomy) or the subsequent management of these patients.

Although there are case series describing experience with tracheotomy in patients with COVID-19, there is not enough evidence to establish firm recommendations. Expert consensus and literature reviews in the context of routine clinical practice therefore may be of help in defining interventions that can guide tracheotomy in relation to this disease.

The current recommendations have been developed by the Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine and Coronary Units (SEMICYUC), the Spanish Society of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery (SEORL-CCC) and the Spanish Society of Anesthesiology and Resuscitation (SEDAR). These recommendations are subject to changes in scientific evidence, and can be adapted to the resources available in each moment.

Methodology of the recommendationsIn view of the COVID-19 pandemic and the need to establish recommendations to help professionals in decision making referred to certain clinical procedures - in this case tracheotomy - the SEMICYUC, SEORL-CCC and SEDAR created an ad hoc group. A literature search was made, and the recommendations were established through consensus based on the findings of the search.

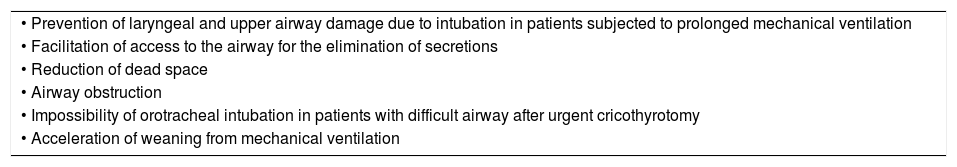

ResultsTables 1 and 2 describe the indications and contraindications referred to tracheotomy.

Indications of tracheotomy in the Intensive Care Unit.

| • Prevention of laryngeal and upper airway damage due to intubation in patients subjected to prolonged mechanical ventilation |

| • Facilitation of access to the airway for the elimination of secretions |

| • Reduction of dead space |

| • Airway obstruction |

| • Impossibility of orotracheal intubation in patients with difficult airway after urgent cricothyrotomy |

| • Acceleration of weaning from mechanical ventilation |

Source: Añón et al.10.

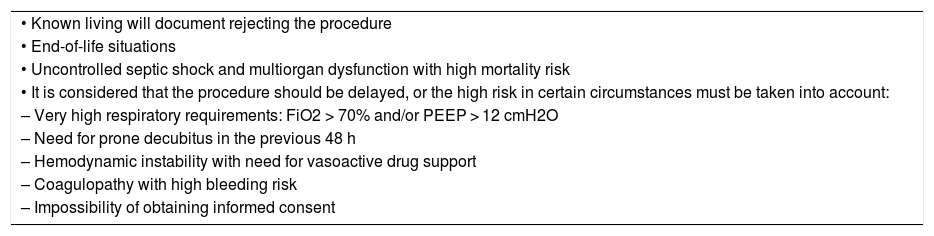

Contraindications of tracheotomy.

| • Known living will document rejecting the procedure |

| • End-of-life situations |

| • Uncontrolled septic shock and multiorgan dysfunction with high mortality risk |

| • It is considered that the procedure should be delayed, or the high risk in certain circumstances must be taken into account: |

| – Very high respiratory requirements: FiO2 > 70% and/or PEEP > 12 cmH2O |

| – Need for prone decubitus in the previous 48 h |

| – Hemodynamic instability with need for vasoactive drug support |

| – Coagulopathy with high bleeding risk |

| – Impossibility of obtaining informed consent |

In routine clinical practice, outside the context of COVID-19, no conclusive data are available on the optimum timing of tracheotomy in the critically ill. This is due to the heterogeneity of the patients included in the studies, the different definitions of early and late tracheotomy employed, and even defects in patient randomization in the clinical trials made. All this means that it is not possible to clearly establish the impact of the timing of tracheotomy in the critically ill upon the outcomes obtained. In the context of patients with COVID-19, it may be appropriate to define early tracheotomy as the technique performed in the first 10 days, while late would refer to tracheotomy performed beyond that time.

Laryngotracheal stenosis following intubation is a well-known risk of prolonged orotracheal intubation, though systematic reviews have not shown the incidence of this complication to be significantly lower in patients subjected to early tracheotomy.11,12

It could be postulated that early tracheotomy does not afford benefits in terms of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) or mortality, though it seems reasonable to perform the technique in patients who are very likely to need prolonged MV - due to its advantages versus intubation in relation to patient wellbeing, ICU stay and duration of MV.13 A recent meta-analysis only reported results regarding a decrease in sedation needs in relation to the timing of tracheotomy.14

Early tracheotomy can increase the contagion risk in patients with COVID-19 and a positive PCR test with a greater viral load. Although the viral clearance rate is not precisely known, in critical patients the viral presence could persist during 2-3 weeks.15 As a result, there are recommendations from scientific societies establishing the criterion of a negative PCR test for performing the technique - an exception being those patients in which orotracheal intubation is unable to secure the airway.16,17 In situations where there may be a scarcity of certain equipment, such as ventilators, early tracheotomy could increase the availability of such resources by reducing the days of MV. This would facilitate access for a larger number of patients with indications of MV. In these circumstances, early tracheotomy may facilitate tracheotomy and nursing care.

A recent study (with data pending publication) has found tracheotomy to allow the suspension of MV an average of four days later, in both early (< 10 days) and late tracheotomies.

At the other extreme, late tracheotomy may serve to better identify patients in which the procedure does not prove useful due to posterior complications such as dysfunction of other organs - with an increased mortality risk - or patients with a better prognosis who will evolve equally favorably and can be extubated. It seems that patients failing to show clinical or radiological remission within 10 days may be more likely to require continuous ventilation and exhibit a more serious course of the disease, including possible death.18

It is advisable to perform tracheotomy in patients with positive PCR testing for COVID-19 from day 14 of orotracheal intubation, and to only consider early tracheotomy in stable patients with a low oxygen demand in which prolonged MV is expected due to other reasons. Early tracheotomy could be considered to optimize the ICU resources.

Surgical tracheotomy versus percutaneous tracheotomyWith regard to the type of procedure, outside the context of COVID-19, there is currently not enough evidence to establish preferences for one type of tracheotomy procedure over another. The decision to use one technique or other can only be based on clinical criteria, experience, and availability. In the current situation of heavy care burden, where the ICU resources are limited, surgical tracheotomy performed by specific surgical teams may favor the procedure and avoid needless delays. It is advisable to consider open tracheotomy or percutaneous tracheotomy (PT) at the discretion of the multidisciplinary team, based on the experience of the center and the availability of the different resources. If on the basis of experience and in the setting of a multidisciplinary team PT is taken to be the technique of choice, then its known contraindications must be considered.

Although the use of fiberoptic bronchoscopy could reduce the risks associated to PT,19 it would not be advisable in patients with COVID-19, since the technique implies an increase in the number of intervening individuals and involves a high risk of aerosol production. If fiberoptic bronchoscopy is considered necessary, it is advisable to use parts that ensure sealing of the insertion of the instrument, and to consider the use of disposable devices.20,21

In these cases, and although there is not enough evidence to recommend its use, in order to reduce the complications associated to the procedure, ultrasound might be useful for increasing precision of the puncture site in patients with difficulties for identifying the anatomical structures.22

In both cases, cleaning of the equipment used must be considered in accordance with the established recommendations.

In patients without significant anatomical alterations of the neck, PT may be regarded as the technique of choice considering the aforementioned recommendations and the availability of trained professionals for performing it. Compared with PT, surgical tracheotomy would allow more controlled and faster access to the airway in patients with a high risk of complications.23 It could be considered in the pandemic stages that produce greater burdens for the professionals in the ICU.

Where to perform tracheotomyPoint of care PT (i.e., at the patient bedside) avoids the need for transfer and suspension of MV, provided it can be performed in individual rooms or negative pressure rooms.

It is advisable to perform tracheotomy in an ICU box or nearby location (such as an operating room) equipped with an isolation system and negative pressure, and with the means needed for the procedure. It is not advisable to perform the technique in COVID-19 patient cohort areas without isolation units. If performed in the operating room, specific considerations apply, with duly marked zones for moving the patient and for carrying out the procedure.24

Surgical technique25–29General recommendations- •

Use of standard tracheotomy surgical material.

- •

As far as possible, we should limit the use of electrical or ultrasound cutting and coagulation systems, or any other devices capable of spreading airborne macroparticles. It is preferable to use cold material and conventional hemostasis systems, except if they cause too much delay in performing the technique.

- •

Closed circuit aspiration systems with antiviral filters are to be used.

- •

The number of staff members present during the procedure should be kept to the necessary minimum.

- •

The most experienced staff possible should perform tracheotomy, in the shortest time possible.

- •

Adequate protective measures are required. PPE: gown, cap, and disposable and impermeable shoe covers; fully sealing facial screen and eye protection (made of plastic and disposable); FFP2 or FFP3 mask or equivalent (N95) and overlying surgical mask. Double surgical gloves are to be preferred.

- •

The goggles, coveralls or similar items are to be tightly sealing. Anti-fogging or similar elements are advisable.

- •

Choose between PT or surgical tracheotomy conditioned mainly to the routine protocol of the center.

- 1

Before opening the trachea:

- •

Ensure adequate pre-oxygenation of the patient (100% oxygen, 5 min).

- •

Complete muscle relaxation of the patient throughout the procedure and particularly at the time of withdrawal of intubation and decannulation, and order to avoid coughing and aerosol production.

- •

Mechanical ventilation is to be suspended before tracheal opening.

- •

- 2

Perform tracheotomy, withdraw the endotracheal intubation tube to the point where the cannula can be positioned with the balloon, without withdrawing it completely; insufflate the cannula balloon.

- 3

Turn on the ventilator, and when correct ventilation has been confirmed (preferably using capnography), withdraw the endotracheal tube and affix the tracheotomy cannula with tape and silk stitches. The tracheotomy cannula balloon must not be deflated once MV has started.

- 4

Collect all the tracheotomy material.

- 5

Remove the surgeon protective material in the operating room or other space according to the applicable norms.

- 6

Leave the operating room or other space according to the applicable norms.

In certain cases, conditioned by ventilatory deterioration of the patient, tracheotomy may have to be performed on an urgent basis in individuals that have not been previously intubated. In these cases cricothyrotomy may be required, using a specific kit.

Urgent tracheotomy is to be avoided as far as possible since it is performed under non-ideal conditions. Good communication with the Departments of Intensive Care Medicine, Anesthesia and Emergency Care is advised, with due assistance in the case of intubations that are expected to be difficult.

- 1

Ensure adequate pre-oxygenation of the patient (100% oxygen, 5 min).

- 2

Complete muscle relaxation to avoid patient movements and coughing.

- 3

Place the tracheotomy cannula and insufflate the balloon.

- 4

Turn on the ventilator and stabilize the patient.

- 5

Affix the cannula.

- 6

If tracheotomy is not possible, cricothyrotomy using the standard technique is indicated.

- 7

If cricothyrotomy has been performed, protocolized tracheotomy is to be performed once the patient has been stabilized and the airway is safe, using a different incision. The cricothyrotomy incision is to be closed after removal of the previous cannula and placement of the cannula in the tracheotomy.

- 8

Analogous to points 4-6 of the previous section (elective tracheotomy).

The care of tracheotomized COVID-19 patients can increase healthcare staff exposure and the risk of spreading the infection.

- •

Allocate the patients to cohort zones according to the COVID-19 situation and risk of contagion.

- •

Patients preferably should be allocated in individual rooms with negative pressure, if available.

- •

The use of PPE during the care of tracheotomized patients always must comply with the recommendations referred to procedures that can generate aerosols - particularly in patients with still positive PCR test results. Such use comprises an impermeable gown, respiratory protection with FPP2 or FFP3 mask, anti-splashing eye protection and gloves. Correct hand hygiene is required before putting on the PPE and after it is removed.10

- •

Tracheotomized patients are to be fitted with a surgical mask over the tracheostomy or over the nasal catheter or oxygen mask if the tracheotomy is closed.

- •

In life-threatening emergency situations, priority should focus on putting on the PPE and calling for help.

- •

Extra PPE kits are to be available in tracheotomized patient areas.

- •

Tracheotomy manipulation and the number of intervening professionals must be kept to a minimum.

- •

Consider a delay in first replacement of the tracheotomy cannula and perform the successive replacements after negative conversion of the virus detection tests.

- •

The use of internal cannulas should be considered in all cases.

- •

Keep the balloon insufflated at all times.

- •

Use closed circuit aspiration systems.

- •

The frequency of tracheostomy cleaning or garment replacement should be adjusted assessing the risk and benefit.

- •

Avoid active humidification and assess the risks and benefits related to cannula obstruction.

- •

Use high-efficiency antimicrobial filters and heat exchangers for MV disconnection.

- •

It is preferable to avoid T-tubes, fenestrated cannulas, and balloon deflation until negative conversion of the virus detection tests.

- •

Multidisciplinary teams trained in tracheostomy management are advised in the case of these patients.

- •

There must be specific resources available for restoring the tracheotomy in the event of decannulation failure.

- •

A system for alerting the Otolaryngology (ENT) Department must be available.

- •

Vision and communication among the team members can be complicated by the use of PPE. Anticipation of the procedures in tracheotomies is required, with the use of short briefing sessions.

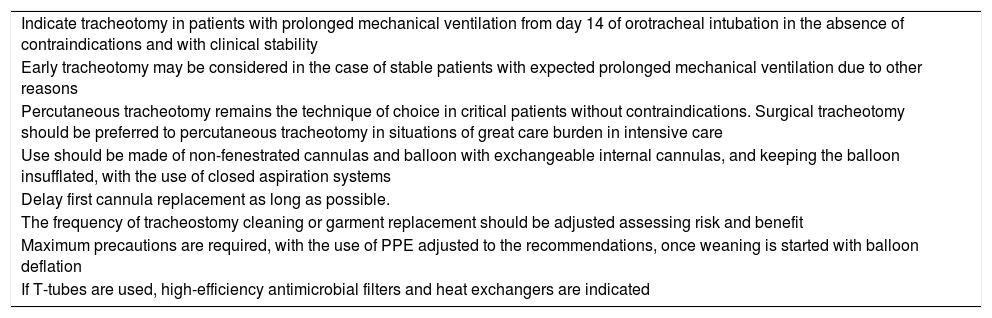

Table 3 summarizes the main conclusions of the consensus document in reference to tracheotomy in patients with COVID-19.

Recommendations regarding tracheotomy in patients with COVID-19.

| Indicate tracheotomy in patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation from day 14 of orotracheal intubation in the absence of contraindications and with clinical stability |

| Early tracheotomy may be considered in the case of stable patients with expected prolonged mechanical ventilation due to other reasons |

| Percutaneous tracheotomy remains the technique of choice in critical patients without contraindications. Surgical tracheotomy should be preferred to percutaneous tracheotomy in situations of great care burden in intensive care |

| Use should be made of non-fenestrated cannulas and balloon with exchangeable internal cannulas, and keeping the balloon insufflated, with the use of closed aspiration systems |

| Delay first cannula replacement as long as possible. |

| The frequency of tracheostomy cleaning or garment replacement should be adjusted assessing risk and benefit |

| Maximum precautions are required, with the use of PPE adjusted to the recommendations, once weaning is started with balloon deflation |

| If T-tubes are used, high-efficiency antimicrobial filters and heat exchangers are indicated |

All these recommendations are based on the current evidence and knowledge of the specialists involved regarding acute respiratory failure secondary to pneumonia due to COVID-19, and it is probable that some indications will change or require adaptation to the resources available in each center in the course of the pandemic.

Authorship/collaboratorsRosa Villalonga Vadell and Manuel Bernal-Sprekelsen have contributed equally as senior authors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Martín Delgado MC, Avilés-Jurado FX, Álvarez Escudero J, Aldecoa Álvarez-Santuyano C, de Haro López C, Díaz de Cerio Canduela P, et al. Documento de consenso de la Sociedad Española de Medicina Intensiva, Crítica y Unidades Coronarias (SEMICYUC), la Sociedad Española de Otorrinolaringología y Cirugía de Cabeza y Cuello (SEORL-CCC) y la Sociedad Española de Anestesiología y Reanimación (SEDAR) sobre la traqueotomía en pacientes con COVID-19. Med Intensiva. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medin.2020.05.002

This article is simultaneously published in Medicina Intensiva (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medin.2020.05.001), in Acta Otorrinolaringológica Española (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otorri.2020.04.002) and in Revista Española de Anestesiología y Reanimación (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redar.2020.05.001), with the consent of the authors and the editors.