Many studies have demonstrated the importance of oral hygiene in the prevention of nosocomial pneumonia among patients admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). The adoption of oral health care protocols for reducing the risk of hospital infections and systemic disorders is also of great importance in the public and private healthcare setting.1

Such infections are commonly acquired as a result of aspiration of the mucous contents in the mouth and pharynx, and are related to the percentage presence of dental biofilm in patients admitted to the ICU – a percentage that increases with the duration of admission.2 Biofilm can act as a reservoir for respiratory pathogens that are well protected against the host defense mechanisms, becoming more resistant to antibiotic treatment and more difficult to eliminate.3,4

In the concrete case of nosocomial infections caused by gramnegative microorganisms, ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is the most common pulmonary infection in the ICU, and develops 48-72hours after endotracheal intubation and the start of invasive mechanical ventilation – with an associated 40% increase in mortality risk.5,6

Simple measures such as patient tooth brushing twice a day and the use of oral antiseptics are able to reduce morbidity-mortality in the ICU. However, it is necessary to individualize each case according to the clinical condition of the patient, in order to ensure that the correct protocol is used. In this context, conscious and intubated patients differ both in the type of microbial colonization of the oral cavity and in the required treatment.7

Considering the above, we carried out a study of two oral hygiene protocols in patients admitted to the ICU of Hospital Evangélico de Londrina-PR (Brazil) in order to compare their efficacy in reducing dental biofilm and bacteria in saliva.

A pilot study was carried out between February and July 2017 in the mentioned ICU, involving patients of either sex and over 18 years of age. The patients were subjected to mechanical ventilation with orotracheal intubation or tracheostomy, a nasogastric tube and parenteral nutrition. Eight volunteers meeting the abovementioned inclusion criteria were included in the study and randomized to two intervention groups:

- –

Group 1: Sterile dressing soaked in aqueous 0.12% chlorhexidine solution and wrapped around the tip of a wooden spatula (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.A) Oral hygiene steps - protocol 1 (group 1): 1A) Hygiene kit; 2A) Spatula wrapped in dressing soaked with oral antiseptic solution (0.12% chlorhexidine digluconate); 3A) Buccal side brushing of the lower right teeth; 4A) Brushing of the lower anterior sector; 5A) Buccal side brushing of the lower left teeth; 6A) Buccal side hygiene of the upper right teeth; 7A) Brushing of the upper anterior sector; 8A) Buccal side brushing of the lower left teeth; 9A) Cleaning of the tube; 10A) Cleaning of the lips. B) Aspiration tooth brush (DentalClean®): 1B) Brush connected to the hospital vacuum aspiration system; 2B) The arrow indicates the aspiration control orifice. The brush only aspirates when the orifice is sealed with the finger; 3B) The arrow indicates the brush aspiration site. Note the sachet containing 0.12% chlorhexidine digluconate gel manufactured and supplied by DentalClean® (Industria Brasilera, Londrina-PR, Brazil). C) Oral hygiene steps - protocol 2 (group 2): 1C) Collector bottle; 2C) Suction tube connection to the hospital vacuum system, with the suction brush; 3C) Connected brush; 4C) Tooth brush soaked in non-alcoholic 0.2% chlorhexidine; 5C) Hygiene kit - 0.12% chlorhexidine gel; 6C) Brushing movements, pressing the brush lightly against the upper right gingiva; 7C) Brushing movements, pressing the brush lightly against the upper anterior gingiva; 8C) Brushing movements, pressing the brush lightly against the upper left gingiva; 9C) Brushing movements, pressing the brush lightly against the lower left gingiva; 10C) Anteroinferior brushing movements; 11C) Brushing movements, pressing the brush lightly against the lower right gingiva; 12C) Soft brushing movements, pressing the brush lightly against the upper right gingiva; 13C) Cleaning of the tongue, from posterior to anterior; 14C) Lip cleaning.

- –

Group 2: A brush connected to the ICU suction system and introduced in the mouth of the patient to first aspirate saliva and residues (Fig. 1B). Then, 0.12% chlorhexidine gel was dispensed in small portions onto the brush and correct brushing was carried out (Fig. 1C).

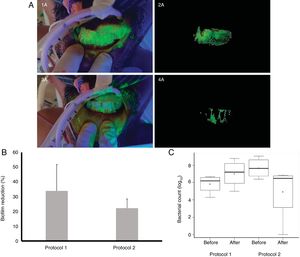

The variation in dental biofilm was assessed using fluorescence with automated recording and digital imaging analysis based on pixel measurement8 (Fig. 2A).

A) Biofilm staining technique: 1A) Intraoral view of fluorescein application before oral hygiene in group 2; 2A) Elimination of the bacterial plaque zone with Adobe Photoshop®; 3A) Intraoral view of fluorescein application after oral hygiene in group 2; 4A) Elimination of the bacterial plaque zone with Adobe Photoshop® after brushing. B) Percentage pixel quantification referred to biofilm reduction before and after the oral hygiene protocols. C) Mean and standard deviation of the total microbial presence before and after oral hygiene.

Dental plaque was evidenced using 1800mg/l of fluorescein sodium (Sigma-Aldrich®) diluted in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at a pH of 7.2 as indicator solution.9

Percentage pixel quantification of the biofilm before and after oral hygiene (Fig. 2B) revealed no significant biofilm reduction with the two protocols. In group 1 the total microbial count before oral hygiene was 5.84 log10 CFU/ml, followed by an increase to 7.04 log10 CFU/ml after oral hygiene. In group 2 the total microbial count before oral hygiene was 7.69 log10 CFU/ml, followed by a decrease to 4.95 log10 CFU/ml after oral hygiene. Although the difference failed to reach statistical significance (t-test, p <0.05)(Fig. 2C), it is important to note that brushing and aspiration proved effective in reducing the oral microbiota (group 2).

Although scantly documented, concern about oral infections as a primary source of systemic infectious processes in totally dependent patients admitted to the ICU has been a relevant element in interdisciplinary team discussions. The measures seeking to reduce infections of oral origin include local hygiene techniques and care.10

The second hygiene protocol (group 2) was seen to be more effective, since it reduced the presence of bacterial plaque as evidenced by pixel quantification, and lowered the bacterial count in the hospitalized patients subjected to mechanical ventilation.

We thus underscore the importance of correct oral hygiene in preserving oral and systemic health among patients admitted to the ICU. Our study used a new hygienization technique for patients in the ICU that may be extended to other bedridden dependent patients, whether in hospital or elsewhere. An efficient oral brushing technique may reduce the presence of pathogenic bacteria in patient saliva.

FundingThe present study received no funding from organizations.

TBSZ thanks DentalClean®, one of the leading tooth brush and dental gel, antiseptic and floss manufactures in Latin America, for kindly donating the special brushes used in this study.

Please cite this article as: Santos Zambrano TB, Poletto AC, Gonçalves Dias B, Guayato Nomura R, Junior Trevisan W, Couto de Almeida RS. Evaluación de un protocolo de cepillado dental con aspiración en pacientes hospitalizados en la unidad de cuidados intensivos utilizando análisis de imagen y microbiología: estudio piloto . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medin.2019.06.003.