T lymphotropic viruses, types i (HTLV-I) and ii (HTLV-II) were the very first retroviruses ever identified in human beings. The HTLV-I virus causes tropical spastic paraparesis or HTLV-I-related myelopathy (degenerative neurological disease), T-cell leukemia in the adult, and other conditions like B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, uveitis, arthritis, and dermatitis.1,2 The HTLV-II, however, has not been clearly associated with any diseases or conditions yet, but traditionally the screening microbiologic analysis always includes the HTLV I/II. Most HTLV-I-positive patients never develop clinical signs, yet high viral loads or immunosuppression due to HIV co-infection or immunosuppressant drugs may lead to developing the disease. These viruses are endemic in places like Japan, Sub-Saharan Africa, the Caribbean, and Central and South American where between 6% and 37% of all healthy adults over 40 are HIV-positive. Transmission happens through sexual intercourse, parenteral route, and mother-to-baby contact through breastfeeding. To categorize a geographical area as endemic, some authors suggest that the prevalence of HTLV-I in some populations should be between 1% and 5%.3

The transmission of HTLV-I through blood transfusions has been reported in multiple studies and the screening for antibodies against HTLV I/II viruses is mandatory in the blood banks of several countries.4 Nowadays in Spain and other countries, only the HTLV-I is screened to look for the presence of antibodies in blood and organ donors with risk factors.5 The transmission of HTLV after transplantation of solid organs from infected donors has been documented extensively.6,7 Back in 2003, the first 3 cases of HTLV-I transmission after transplantation of 1 liver and 2 kidneys from the same infected donor8–11 were reported. All organ receivers presented with tropical spastic paraparesis that lead to paralysis or very high disability.

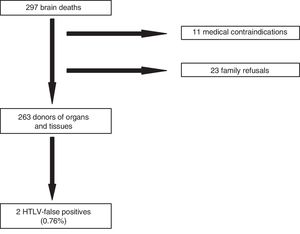

Taking into consideration the importance of the transmission of this infection through solid organ transplantation, we studied the prevalence of antibodies against HTLV I/II lymphotropic viruses in potential organ donors of Asturias, Spain. Then we analyzed all brain deaths that occurred in the intensive care units from 2014 through 2018, both years included. We collected epidemiological data and serological test results for the HTLV I/II viruses in potential organ donors after excluding negative and medical contraindications for donation. The risk factors for HTLV I/II infection analyzed were the geographical region of birth/habitual residence, drug addiction through parenteral route, and high-risk sexual activity. The screening for antibiotics was conducted using the chemiluminescent assay (CLIA) with the Liaison XL automated system (Liaison® XL murex recHTLV-I/II, DiaSorin). This system detects anti-HTLV-I and anti-HTLV-II antibodies simultaneously without discriminating HTLV-I from HTLV-II antibodies. The CLIA-positive specimens were confirmed in a second ELISA test and then sent to Instituto de Salud Carlos III for Western Blot confirmation test. The CLIA technique was conducted for 1h and the cost of the chemically reactive agent were €3. Conducting this test meant no delay in the logistics of the donation process. A total of 297 brain deaths were analyzed. Of these, 11 were discarded due to medical contraindication and 23 due to refusal to donate (Fig. 1). Of the 263 brain deaths that were organ donors, 139 (52.9%) were males and 124 (47.1%) were women with a mean age of 62.4 years and an average hospital stay from admission until organ extraction of 4.73 days. Eight hundred and forty-one organs were extracted from these donors, out of which 610 were transplanted. Regarding nationality, only 9 donors (3.4%) were foreigners out of which 4 (1.5%) came from countries at risk (Colombia, Cuba, Dominican Republic, and Peru). Regarding other risk factors, only 1 donor (0.4%) was involved in high-risk sexual activity. Two potential donors (0.76%) tested HTLV I/II-positive in the CLIA, one of them with a threshold value of 1.3 arbitrary units (upper limit of normal: 1.0) that was considered a false positive. In the other one, the CLIA showed 4.0 arbitrary units and was discarded as a donor. The Western Blot tested negative in both cases confirming the false positive results, representative of 0.76% of all determinations. These results conditioned the loss of 1 donor. In light of our study, we concluded that the seroprevalence for HTLV I/II in potential organ donors in Asturias is low. However, the progressive increase of migration flows, the difficulty obtaining risk factors in the clinical history, and the rate of asymptomatic unaware HTLV I carriers may increase the risk of HTLV transmission through organ transplants. On the other hand, transplanted patients on immunosuppressant therapy have more chances of developing HTLV-I-related conditions that are associated with a higher mortality rate and significant disability. Therefore, to improve the quality and safety of transplanted organs, the next review of the Study Group on Infection in Compromised Hosts Consensus Document from the Transplant Infection and National Transplant Organization of the MSC on selection criteria of donors regarding the transmission of infections12,13 will be recommending the universal screening for HTLV-I with serological tests of all organ donors.

Conflicts of interestNone reported.

Please cite this article as: Leizaola Irigoyen O, Leoz Gordillo B, Balboa Palomino S, Rodríguez Perez M, Mahillo Durán B, Escudero Augusto D. Seroprevalencia de anticuerpos frente a virus linfotrópicos humanos (HTLV I y II) en donantes de órganos. Med Intensiva. 2020;44:451–453.