Invasive mechanical ventilation in the prone position with 16 h-sessions reduces the mortality rate of patients with moderate and/or severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).1

Despite of this, its use in the routine clinical practice is much less generalized than it should, and <50% of the patients with an indication receive this technique.2 However, its use during the COVID-19 pandemic has reached rates above 80%.3,4 This is probably due to the high perception of severity there was during the peak of the pandemic.

Going from the supine to the prone position is a complex procedure that requires time and experienced personnel. It is not a risk-free procedure, and displacements of the orotracheal tube and vascular devices, hemodynamic instability or cases of cardiac arrest have been reported.5

During the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workers have been flooded with work followed by high levels of physical exhaustion, and emotional stress.6 This adds to the lack of experience in the routine clinical practice with the prone position technique by other healthcare personnel that came to help to the intensive care units.

In view of this situation, and to optimize resources and reduce the risk of complications, some centers decided to create dedicated teams with the sole task of performing this procedure.7 In our unit we engaged in prone sessions of up to 48 h instead of the recommended 16 h/day to reduce the total number of changes of position.

The efficacy of the prone position in terms of mortality was confirmed when the sessions, that extended for 8 h/day during the first studies, went on for another 8 h (16 h total).5 However, we still do not know if more hours in the prone position could increase the benefit of this technique. It is plausible to think that with more hours in the prone position the chances of ventilation-induced lung injury are much lower. The risks associated with this increase in the number of hours in the prone position can be facial edema, pressure ulcers, orotracheal tube obstructions, enteral nutrition intolerance, and joint and eye problems.5

The medical literature available on prolonged prone positioning is scarce. We only know of 2 articles that speak of its feasibility, and safety with satisfactory results.8,9

We describe our experience with 17 consecutive patients hospitalized due to COVID-19 and ARDS between March and August 2020. This was a prospective series of patients with retrospective data mining that starts with the patients’ health records. The objective of the study was to assess the feasibility and safety of the technique, not its physiological implication or clinical benefits. A local research ethics committee has approved the publication of this study.

A total of 100% of the patients were placed in the prone position early at the beginning. The patients’ mean age was 60 ± 11 years, 60% were males, and the mean body mass index was 28 ± 5 kg/m2. On day 1, with the prone position already implemented, the mean tidal volume was 375 ± 30 mL (6 ± 1 mL/kg of ideal weight), the FiO2 was 50 ± 7%, the PEEP was 11 ± 1 cmH2O, and the PaO2/FiO2 ratio was 260 ± 80 mmHg. The mean static compliance was 33 ± 7 mL/cmH2O, the plateau pressure was 23 ± 2 cmH2O, and the driving pressure was 12 ± 2 cmH2O. The mean time patients remained on invasive ventilation was 25 ± 9 days, the mean length of the ICU stay was 32 ± 13 days, and the in-hospital overall mortality rate was 18% (3/17).

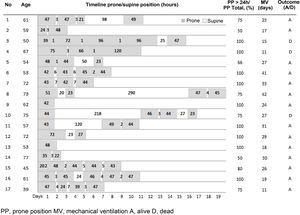

The mean number of sessions in the prone position per patient was 3 ± 1 with a mean duration per session of 46 ± 18 h (Fig. 1). A total of 85% of the sessions exceeded the 24-h mark. The most common adverse event found in 100% of the patients was facial edema (Table 1). The rate of grade ≥ 2 pressure ulcers 7 days after placing the patient in the prone position was 47% in the face, and 29% in the thorax. These rates are higher than those reported by studies with prone sessions of up to 16 h (29% and 18%, respectively).10 Despite of this, both facial edema and grade ≥ 2 pressure ulcers were gone at discharge. None of the patients from the series required total parenteral nutrition so we can assume that tolerance to enteral nutrition was, at least, acceptable. One patient experienced joint issues in his shoulder that probably had to do with the “swimmer” position we used to place him in the prone position. No orotracheal tube obstructions or significant eye problems were reported. The percentage of patients with ventilation-associated pneumonia was 18%, which is somehow similar to the rate reported by studies with ARDS, and 16 h-prone sessions,5 and also to recent series with COVID-19.3,4

Complications of prolonged prone position.

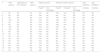

| n | VAP (yes/no) | Obstruction of OTT (yes/no) | TPN (yes/no) | Edema (yes/no) | Pressure ulcersa (yes/no) | Joint problems | Eye problems | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facialb | ICU discharge | Facialb | Thoracicb | ICU discharge | (Yes/No) | (Yes/No) | ||||

| 1 | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| 2 | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 3 | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| 4 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| 5 | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| 6 | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| 7 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 8 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| 9 | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 10 | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 11 | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 12 | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 13 | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 14 | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 15 | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 16 | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 17 | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

ICU, intensive care unit; OTT, orotracheal tube; TPN, total parenteral nutrition; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia.

Our study has limitations. This was a retrospective, single-center study with a small sample and no control group. To generalize its use out of this exceptional situation new experimental studies are required with control groups and focused on the safety profile of this technique.

In conclusion, prolonged ventilation in the prone position with mean sessions of up to 48 h is feasible and reasonably safe. Also, it can be an option for future peaks of the pandemic to reduce the risk involved in every change of position and the workload of healthcare workers.

Please cite this article as: Concha P, Treso-Geira M, Esteve-Sala C, Prades-Berengué C, Domingo-Marco J, Roche-Campo F. Ventilación mecánica invasiva y decúbito prono prolongado durante la pandemia por COVID-19. Med Intensiva. 2022;46:161–163.