A 35-year-old transsexual (male to female) went to emergency with 24h of mild fever, cough and dyspnoea. Four days before he had been submitted to multiple gluteus subcutaneous injections of polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) microspheres. Patient had a past medical history of uncontrolled hypertension.

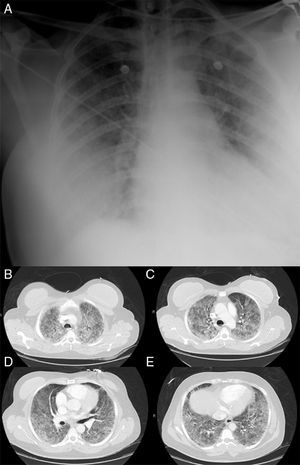

On admission patient had Glasgow Coma Scale Score of 15, tachypnea and tachycardia, with central cyanosis and was sweating. No fever. Blood pressure was 100/70mmHg and respiratory rate 40/min. Arterial blood gas analysis under 15l/min oxygen therapy by a non-rebreathing mask with reservoir showed global respiratory insufficiency and sever acidemia (pH 7.22, pO2 31mmHg, pCO2 49mmHg, HCO3− 17.6mEq/L, SatO2 55%, lactate 6.17mmol/L). Heart auscultation revealed audible S1 and S2 and chest auscultation revealed bilateral rales. The remaining physical examination just was unremarkable with exception of mild redness, warmth and swelling of the gluteus. No fluctuation was detected and no indication for surgical approach was considered. Chest X-ray showed bilateral lung infiltrates (Fig. 1A). At this time was intubated and mechanically ventilated.

On intensive care unit (ICU) admission presented with hypotension, tachycardia, oligoanuric renal failure, mixed acidemia and pO2/FiO2 ratio of 40. Biochemistry showed: normocytic normochromic anaemia, high white blood cells count, coagulation times prolonged, acute renal lesion with hyperkalemia, hyperbilirubinemia 1.49mg/dL [0.3–1.2], conjugated bilirubin 0.79 [0–0.2], hepatic cytolysis high lactate dehydrogenase and C-reactive protein. Patient was started on empirical antibiotic therapy with meropenem due to the inflammatory signs in gluteus.

Electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia with S1Q3T3 pattern. Computed tomography angiography ruled out pulmonary embolism and disclosed bilateral consolidations with air-bronchograms and ground-glass-appearing opacities suggestive of alveolar damage (Fig. 1B–E). Transthoracic echocardiogram revealed normal left ventricular systolic function with no contractility alterations, valve dysfunctions or pericardial effusion.

Pulse contour cardiac output (PiCCO) catheter was placed and haemodynamic monitoring showed low cardiac index (CI), low intrathoracic blood volume index (ITBVI), low central venous oxygen saturation (cvSatO2), high venous-to-arterial CO2 gap (pCO2 gap), high extravascular lung water index (EVLWI) and normal systemic vascular resistance (SVR) on norepinephrine 0.55μg/kg/min. Distributive shock (DS) with vasoplegia, functional hypovolemia and pulmonary oedema complicated with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) was diagnosed (Table 1). Patient was started on vasopressors and continuous renal replacement technique. He developed severe (pO2/FiO2 ratio≤100)1 acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) with need of prone position and curarization.

PiCCO haemodynamic monitoring.

| On admission | After 12h | After 24h | After 36h | After 48h | After 72h | After 96h | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norepinephrine, μg/kg/min | 0.55 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| BP, mmHg | 151/66 | 139/66 | 145/80 | 148/89 | 90/54 | 179/103 | 121/70 |

| HR, bpm | 101 | 100 | 78 | 63 | 62 | 54 | 79 |

| CVP, cm H2O | 13 | 16 | 14 | 16 | 12 | 13 | 10 |

| CI (2.8–3.4) | 2.31 | 3.19 | 2.89 | 2.83 | 2.94 | 2.33 | 3.5 |

| SVR (770–1500) | 1169 | 731 | 1034 | 1115 | 630 | 1720 | 725 |

| EVLWI (3–7) | 21 | 16.7 | 12.4 | 11.3 | 9.8 | 8.2 | 12.4 |

| ITBVI (850–1000) | 486 | 594 | 619 | 676 | 714 | 766 | 1043 |

| paO2, mmHg | 61.5 | 95.3 | 122 | 116 | 70 | 162.6 | 111 |

| aSatO2% | 76 | 94.1 | 96.6 | 96 | 88 | 99.3 | 98 |

| pvO2, mmHg | 29.9 | 54.8 | 52 | 40 | 41 | 32.9 | 43 |

| cvSatO2% | 54 | 79.9 | 79.4 | 67 | 62 | 61.1 | 72 |

| pCO2 gap | 19 | 14.9 | 13.3 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 5.2 |

| FiO2 (21–100%) | 100 | 100 | 80 | 65 | 50 | 70 | 75 |

| PEEP, cm H2O | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 14 | 10 | 12 |

| Lactate, mmol/L | 8.8 | 6.7 | 2.35 | 2.11 | 1.67 | 2.69 | 1.5 |

| Hb, g/dL | 10.9 | 10.8 | 9.6 | 8.6 | 7.7 | 8.5 | 8.3 |

BP, blood pressure; HR, heart rate; CVP, central venous pressure; CI, cardiac index; SVR, systemic vascular resistance; EVLWI, extravascular lung water index; ITBVI, intrathoracic blood volume index; paO2, arterial oxygen partial pressure; aSatO2, arterial oxygen saturation; pvO2, venous oxygen partial pressure; cvSatO2, central venous oxygen saturation; pCO2 gap, venous-to-arterial CO2 gap; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; Hb, haemoglobin.

Serologies for HIV, HBV, HCV, EBV, CMV, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and respiratory virus were negative. Tracheobronchial aspirate, uroculture and pneumococcal and Legionella urinary antigen tests were negative. Three sets of blood culture specimens exhibited no growth. Meropenem stopped on the 5th day of therapy.

Patient remained apyretic, inflammatory markers decreased and gluteus inflammatory signs improved rapidly. Patient remained under continuous renal replacement technique for 5 days with gradual recovery of renal function and vasopressor support was stopped on 2nd day. He was mechanically ventilated for 15 days and was extubated on 16th day.

Chest CT with significant reduction of pulmonary infiltrates. Laboratory tests evidenced recovery of hepatic function with correction of the coagulation disorder.

Patient was transferred to intermediate care on 17th day and then to the general ward, requiring only physical rehabilitation.

Shock is a high mortality acute syndrome characterized by cellular dysoxia, and can lead if not quickly and appropriately managed to organ failure and death. It is classically rated has hypovolemic, cardiogenic, obstructive or distributive. The first three are associated with low CI while distributive shock is associated with normal or supranormal levels of CI,1 impaired distribution of microvascular blood flow and metabolic distress. DS occurs mainly during systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) which can be due to infectious or non-infectious causes. The most common aetiology of DS is septic shock. Non-infectious causes include burns, pancreatitis, toxic shock syndrome, anaphylaxis and drugs or toxins. PMMA is a no biodegradable injectable filling used for a variety of conditions such as percutaneous vertebroplasty and cosmetic soft tissue filling. PMMA subcutaneous injections local complications are nodules, filler migration and granulomas. Mostly described following percutaneous vertebroplasty systemic complications include pulmonary embolism,2 pulmonary embolism with ARDS,3 ventricular perforation,4 intracardiac embolism,5 aortic embolism,6 renal embolism7 and deep vein thrombosis.8

Our patient never had fever. Inflammatory markers decreased rapidly and did not relapse after meropenem has been stopped. No pathogenic organisms were isolated. We assisted to a favourable evolution even in absence of antibiotherapy. These facts make infectious aetiology less probable. Most probable hypothesis due to patient's history of PMMA gluteus subcutaneous injections four days before, absence of positive culture results and favourable evolution just with organ support therapy is SIRS triggered by chemical insult induced by PMMA. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case reported in literature of shock and MODS secondary to subcutaneous injection of PMMA.

Conflicts of interestAll the authors have reported no conflicts of interest.