To measure accessibility to health care among diabetic patients and analyze whether differences in delay explain differences in hospital mortality.

MethodsA retrospective cohort study was conducted in diabetic patients with acute coronary syndrome with ST-segment elevation included in the ARIAM-SEMICYUC registry (2010–2013). Crude and adjusted analyses were performed using unconditional logistic regression.

ResultsA total of 4817 patients were analyzed, of whom 1070 (22.2%) were diabetics.

No differences were found in access to health care between diabetic and non-diabetic patients. Diabetic patients presented with longer patient delay (90min vs. 75min; p=.004) and prehospital delay (150min vs. 130min; p=.002). Once the health system was contacted, diabetic patients had a lower reperfusion rate (50% vs. 57.7%; p<.001), but no longer delay in treatment was observed compared with the non-diabetic individuals. Diabetic patients have greater in-hospital mortality (12.5 vs. 6%; p<.001), though neither patient delay nor prehospital delay was identified as independent predictors of in-hospital mortality.

ConclusionsDiabetic patients had a longer delay in access to health care, though such delay was not independently related to increased mortality.

El objetivo de este estudio es medir la accesibilidad al sistema sanitario de los pacientes diabéticos y analizar si las posibles diferencias en la accesibilidad explican la mayor mortalidad conocida en aquellos.

MétodosEstudio de cohortes retrospectivo, realizado en pacientes diabéticos con síndrome coronario agudo con elevación del segmento ST incluidos en los años 2010 al 2013 del registro ARIAM-SEMICYUC. Se realiza análisis crudo y ajustado mediante regresión logística no condicional.

ResultadosSe han analizado 4817 pacientes, de los cuales 1070 (22,2%) son diabéticos. Los pacientes diabéticos contactan con el sistema sanitario de la misma forma que los pacientes no diabéticos aunque con mayor retraso (retraso atribuible al paciente 90min vs. 75min con p=0,004 y retraso prehospitalario 150min vs. 130min con p=0,002). Una vez dentro del sistema sanitario, estos pacientes tienen menor tasa de reperfusión (50 vs. 57,7%; p<0,001) pero sin objetivar mayor retraso en el tratamiento. Como ya es conocido, los pacientes diabéticos presentan una mayor mortalidad hospitalaria (12,5 vs. 6%; p<0,001); sin embargo, no se identifican como variables predictoras independientes de la mortalidad ni el retraso atribuible al paciente ni el retraso prehospitalario.

ConclusionesLos pacientes diabéticos tienen una mayor demora en el acceso al sistema sanitario, sin embargo no hemos podido objetivar que esta demora se relacione de forma independiente con la mayor mortalidad.

In patients presenting acute coronary syndrome (ACS) with ST-segment elevation (ACSSTE), reperfusion treatment should be provided as soon as possible, and always within the first 12h after symptoms onset.1,2 The total reperfusion time basically comprises two phases: the time taken by the patient to contact the health care system after symptoms onset (patient-attributable delay) and the time from patient contact to the start of reperfusion treatment (health care system-attributable delay).

A number of studies have shown that diabetic patients with ACSSTE take longer in contacting the health care system after symptoms onset,3–7 and this delay has a number of consequences. On one hand it directly influences the decision to perform reperfusion and the choice of treatment provided (fibrinolysis versus percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI]), while on the other hand a longer initial delay contributes to longer total reperfusion times and therefore to more prolonged myocardial ischemia. Of the different factors that may explain this greater delay among diabetic patients, the atypical nature of their symptoms play a particularly important role.3,5,8

The present study aims to determine whether there are differences in accessibility to the health care system (access and reperfusion times) between diabetic patients and no-diabetic individuals. An evaluation is made of the different factors that might influence such differences, and finally an analysis is performed to determine whether differences in delay are able to account for the greater mortality observed among diabetic patients.

MethodsA retrospective cohort study was carried out, based on the data of the ARIAM-SEMICYUC registry, which includes the participation of different Spanish hospitals.9 This registry complies with Spanish legislation on observational post-authorization studies with drugs destined for human use (Order SAS/3470/2009, of 16 December). In addition, recognition as a registry of interest for the national health system was received in May 2012.

Data were collected on those consecutive patients admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU)/Coronary Unit diagnosed upon admission with ACSSTE in the period 2010–2013.

The study variables comprised sociodemographic data (age, gender) and information referred to access to the health care system (place of first contact, form of transfer to hospital), the clinical presentation of ACS (electrocardiogram, first symptom), clinical characteristics upon admission (Killip–Kimball classification, TIMI, GRACE, CRUSADE),10–12 and the reperfusion method used.

Regarding the treatment delays, we analyzed the times attributable to the patient and to the health care system: (a) patient-attributable time (from symptoms onset to first medical contact [FMC]); (b) pre-hospital time (from symptoms onset to arrival in hospital, which coincides with the patient-attributable time in those cases where FMC takes place in hospital); (c) transfer time (in those patients in which FMC does not take place in hospital, this is the time from FMC to arrival in hospital); (d) time from arrival in hospital to administration of fibrinolysis; (e) time from arrival in hospital to PCI; and (f) total reperfusion time censored to 12h (from symptoms onset to reperfusion). We moreover examined mortality in the ICU, in hospital, and after 30 days.

The data were analyzed using the SPSS version 22 statistical package for Mac. In the descriptive statistical analysis, the continuous quantitative variables were expressed as the median and percentiles 25 and 75, while the categorical variables were reported as proportions. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test, while quantitative variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test after confirming non-normal data distribution with the Shapiro–Wilks test. The time variables were analyzed based on Kaplan–Meier survival curves with application of the Breslow test. Two-tailed contrasting of hypotheses was performed, with an alpha level of significance of 5%.

The analysis of mortality was based on the variable hospital mortality, since mortality after 30 days was a non-obligate variable with many data collection losses.

Lastly, binary logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of hospital mortality. Different variables yielding a level of significance of <0.1 in the univariate analysis were entered in the regression model. The association between the predictor variables and mortality was assessed by calculating the adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

ResultsThe study included 4685 patients with ACSSTE, of which 22.85% (1070 subjects) suffered diabetes mellitus.

Table 1 presents the findings of the univariate analysis of the main variables. The diabetic patients were older than the non-diabetic individuals, and females predominated. Acute coronary syndrome manifested differently among the diabetic patients, with more frequent atypical pain or no pain. However, the form of access to the health care system was similar in both groups. In this regard, hospital emergency care was the most common FMC. Likewise, no statistically significant differences were observed in the form of transfer to hospital, though diabetic patients tended to be taken to hospital more often by non-medicalized health care transport means and less often by themselves or by a relative.

Baseline characteristics and evolution. Patients with ACSSTE (n=4817).

| Baseline characteristics | Patients with ACSSTE (n=4817) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DM 22.8% (n=1070/4685) | No DM 77.2% (n=3615/4685) | ||

| Age | 68.5 (60–77) | 62 (52–74) | <0.001 |

| Gender (males) (n=4684) | 795 (74.3%) | 2861 (79.2%) | 0.001 |

| Clinical presentation | |||

| First symptom (n=3575) | 0.003 | ||

| No pain | 42 (5.3%) | 90 (3.2%) | |

| Typical pain | 674 (84.6%) | 2464 (88.7%) | |

| Atypical pain | 81 (10.2%) | 224 (8.1%) | |

| Cardiorespiratory arrest (n=3640) | 37 (4.6%) | 143 (5%) | 0.624 |

| Form of first medical contact (n=4659) | 0.237 | ||

| 061-112 | 208 (19%) | 693 (19.3%) | |

| Physician | 44 (4.1%) | 162 (4.5%) | |

| Primary care center | 317 (29.9%) | 1105 (30.7%) | |

| Hospital emergency care | 396 (37.3%) | 1359 (37.8%) | |

| Hospitalized patients | 33 (3.1%) | 66 (1.8%) | |

| Others | 63 (5.9%) | 213 (5.9%) | |

| Transfer (n=4560) | 0.055 | ||

| Patient-relative | 469 (45.6%) | 1693 (47.9%) | |

| Non-medicalized health care transport | 80 (7.8%) | 196 (5.5) | |

| 061-112 | 394 (38.3%) | 1363 (38.6%) | |

| Others | 85 (8.3%) | 280 (7.9%) | |

| ECG upon admission (n=4589) | <0.001 | ||

| ST elevation >2mm on >2 leads | 787 (75%) | 2787 (78.7%) | |

| ST elevation <2mm or on <2 leads | 230 (21.9%) | 709 (20%) | |

| New CLBB | 32 (3.1%) | 44 (1.2%) | |

| Severity upon admission | |||

| Initial KK (n=4634) | <0.001 | ||

| 1–2 | 923 (87.1%) | 3333 (93.3%) | |

| 3–4 | 137 (12.9%) | 241 (6.7%) | |

| TIMI (n=3466) | <0.001 | ||

| <4 | 266 (34.5%) | 1292 (48%) | |

| ≥4 | 506 (65%) | 1402 (52%) | |

| GRACE (n=4635) | 160 (139–185) | 146 (125–172) | <0.001 |

| CRUSADE (n=4645) | 47 (29–57) | 37 (20–49) | <0.001 |

| Reperfusion rate (n=4666) | 534 (50%) | 3599 (57.7%) | <0.001 |

| Reperfusion method (n=4666) | <0.001 | ||

| None | 194 (18.2%) | 525 (14.6%) | |

| Thrombolysis | 271 (25.4%) | 1067 (29.6%) | |

| Primary PCI | 463 (43.4%) | 1635 (45.4%) | |

| Delayed PCI | 139 (13%) | 372 (10.3%) | |

| Mortality | |||

| In ICU (n=4515) | 82 (8%) | 121 (3.5%) | <0.001 |

| In hospital (n=3746) | 109 (12.5%) | 175 (6%) | <0.001 |

| After 30 days (n=2634) | 116 (19.2%) | 201(9.9%) | <0.001 |

CLBB: complete left bundle block; DM: diabetes mellitus; ECG: electrocardiogram; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; KK: Killip–Kimball; ACSSTE: acute coronary syndrome with ST-segment elevation; ICU: Intensive Care Unit.

Upon arrival in emergency care, the diabetic patients showed a greater presence of complete left bundle block on the ECG tracing, greater heart failure as assessed by the Killip–Kimball score, and increased severity as determined from TIMI, GRACE and CRUSADE. Furthermore, they presented lower reperfusion rates, with less thrombolysis and PCI and a higher late PCI rate. Mortality in the ICU, in hospital and after 30 days was also higher among the diabetic subjects.

Table 2 shows the analysis of the times attributable to the patient and to the health care system. Diabetic patients were seen to take longer in establishing FMC. This was attributable to a longer pre-hospital delay–the time of transfer to hospital being similar in both patient groups. Once the patient had established contact with the health care system, no differences were observed in the treatment times (emergencies-needle time, emergencies-balloon time, FMC-needle time, FMC-balloon time). All times calculated from symptoms onset were longer among the diabetic patients, since they were influenced by patient-attributable delay (symptoms-needle time, symptoms-balloon time, total reperfusion time).

Times related to patient-attributable delay and health care system-attributable delay (expressed in minutes, with median and interquartile range).

| Times | Patients with ACSSTE (n=4817) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DM 22.85% (n=1070/4685) | No DM 77.17% (n=3615/4685) | ||

| Patient delay (n=3382) | 90 (40–210) | 75 (31–183) | 0.004 |

| Pre-hospital delay (n=3709) | 150 (82–284) | 130 (72–267) | 0.002 |

| Transfer delay (n=1879) | 57 (30–90) | 53 (26–86) | 0.18 |

| Symptoms-needle time (n=1297) | 180 (120–270) | 150 (100–250) | 0.005 |

| FMC-needle time (n=934) | 80 (50–128) | 70 (40–115) | 0.115 |

| Emergencies-needle time (n=1003) | 49 (30–84) | 42 (28–75) | 0.126 |

| Symptoms-balloon time (n=2554) | 450 (210–1956) | 375 (190–1560) | 0.012 |

| FMC-balloon time (n=1413) | 134 (95–225) | 125 (90–196) | 0.079 |

| Emergencies-balloon time (n=1227) | 113 (70–192) | 105 (62–169) | 0.065 |

| Total reperfusion time (n=2608) | 195 (135–285) | 175 (120–270) | 0.002 |

DM: diabetes mellitus; FMC: first medical contact; ACSSTE: acute coronary syndrome with ST-segment elevation.

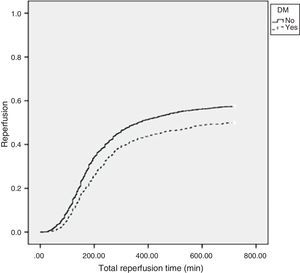

The analysis of the relationship between total reperfusion time and the reperfusion event showed the diabetic patients to be less likely to be reperfused versus the non-diabetic patients (Fig. 1).

The following variables were entered in the regression model: diabetes mellitus, age, patient-attributable delay, reperfusion event, Killip–Kimball score, TIMI, GRACE, CRUSADE, and total reperfusion time. Diabetes and patient severity (TIMI, GRACE and CRUSADE) were identified as independent mortality predictors, though not so patient-attributable delay (Table 3). Furthermore, application of the equation obtained with the model and calculation of the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (=0.9) indicated a very good predictive capacity of the regression model.

Binary logistic regression model.

| Predictor variables | OR (95%CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-attributable delay (h) | 1.017 (0.995–1.041) | 0.129 |

| DM | 1.51 (1.046–2.181) | 0.028 |

| TIMI | 2.314 (1.106–4.841) | 0.026 |

| GRACE | 1.031 (1.025–1.036) | <0.001 |

| CRUSADE | 1.031 (1.017–1.045) | <0.001 |

DM: diabetes mellitus; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

In the present study diabetic patients were seen to present greater patient-attributable delay; as a result, all the times that included this parameter were prolonged in comparison with the non-diabetic individuals. Other authors have published similar findings. The studies of Hasin et al., Woodfield et al. and Goldberg et al. have described longer intervals between symptoms onset and treatment among diabetics compared with non-diabetic individuals.3–5 Ribeiro et al. analyzed patients with ACSSTE according to pre-hospital delay, and found that the group with the longest delays included a larger proportion of diabetic individuals. Furthermore, they identified diabetes as an independent predictor of pre-hospital delays of over 3h.6 Goldberg et al., in a study published after that mentioned above, analyzed data from 14 countries, including Spain (North and South America, Europe, Australia and New Zealand), and found diabetic patients in all these geographical settings to have greater pre-hospital delays.7 However, none of above publications analyzed the possible relationship between this greater pre-hospital delay in diabetics and their increased mortality. In our series, accessibility to the health care system was seen to be similar in diabetic and non-diabetic patients, and once the patients came into contact with the system, the calculated times were similar in both groups. In the year 2002, Colmenero-Ruiz et al. analyzed the differences in the management of patients with ACS among the different Spanish Autonomous Communities, based on the ARIAM registry. They found differences in the form of access to the health care system in the different Communities analyzed, though this was not associated to differences in mortality. There was also important variability in the percentage of diabetic patients from one community to another. However, the possible association between diabetes and the form of access has not been investigated.13 Another finding in our study is the fact that diabetic patients more often experienced atypical symptoms or no pain, which can explain the longer times taken in seeking help. This is consistent with the findings of other authors.5 Leslie et al. analyzed the different causes of pre-hospital delay in patients with ACS–the most frequent reason being problems in correctly interpreting the symptoms and a lack of awareness of the seriousness of the condition.8 In our study we moreover found diabetic patients to have a lesser reperfusion rate and higher mortality–in coincidence with the data reported in the literature.14

Our study was unable to establish an independent association between patient-attributable delay and mortality. The results obtained indicate that the variables independently associated to mortality in patients with ACSSTE are increased initial severity as determined from the TIMI, GRACE and CRUSADE scores, and the existence of diabetes mellitus.

The main limitation of our study is referred to patient follow-up from hospital discharge. For the mortality analysis we decided to use the variable hospital mortality, due to the large data losses associated to the variable mortality after 30 days–though we also consider such losses to be random, and therefore feel that they do not bias our results.

On the other hand, this is a multicenter study involving centers from all over Spain–a fact that ensures a study sample clearly representative of the Spanish population.

ConclusionDiabetic patients take longer in contacting the health care system, though what appears to condition the increased mortality observed in these patient is not the delay in FMC but the fact of having diabetes and the increased severity of the patient condition at hospital admission.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Baeza-Román A, de Miguel-Balsa E, Latour-Pérez J, Díaz de Antoñana-Saez V, Arguedas-Cervera J, Mira-Sánchez E, et al. Accesibilidad al sistema sanitario de los pacientes diabéticos con síndrome coronario agudo con elevación del segmento ST. Med Intensiva. 2016;40:90–95.

The members of the ARIAM-SEMICYUC Group work in Intensive Care / Coronary Units of several Spanish hospitals.