Contribution to validation of the Braden scale in patients admitted to the ICU, based on an analysis of its reliability and predictive validity.

DesignAn analytical, observational, longitudinal prospective study was carried out.

SettingIntensive Care Unit, Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Seville (Spain).

PatientsPatients aged 18years or older and admitted for over 24h to the ICU were included. Patients with pressure ulcers upon admission were excluded. A total of 335 patients were enrolled in two study periods of one month each.

InterventionsNone.

Variables of interestThe presence of grade I–IV pressure ulcers was regarded as the main or dependent variable. Three categories were considered (demographic, clinical and prognostic) for the remaining variables.

ResultsThe incidence of patients who developed pressure ulcers was 8.1%. The proportion of grade I and II pressure ulcer was 40.6% and 59.4% respectively, highlighting the sacrum as the most frequently affected location. Cronbach's alpha coefficient in the assessments considered indicated good to moderate reliability. In the three evaluations made, a cutoff point of 12 was presented as optimal in the assessment of the first and second days of admission. In relation to the assessment of the day with minimum score, the optimal cutoff point was 10.

ConclusionsThe Braden scale shows insufficient predictive validity and poor precision for cutoff points of both 18 and 16, which are those accepted in the different clinical scenarios.

Contribuir a la validación de la escala de Braden en el paciente ingresado en la UCI mediante un análisis de su fiabilidad y validez predictiva.

DiseñoAnalítico, observacional, longitudinal y prospectivo.

ÁmbitoUnidad de Cuidados Intensivos del Hospital Virgen del Rocío (Sevilla).

PacientesSe incluyeron los pacientes de 18años o más que permanecieron ingresados en la unidad durante más de 24h. Fueron excluidos los pacientes que presentaron úlceras por presión al ingreso. En total, 335 pacientes fueron incluidos durante dos períodos de estudio de un mes de duración cada uno de ellos.

IntervencionesNinguna.

Variables de interés principalesComo variable principal se consideró la aparición de UPP en estadios del I al IV. Para el resto de variables se tomaron 3 categorías: demográficas, clínicas y de pronóstico.

ResultadosLa incidencia de pacientes que desarrollaron úlceras por presión fue del 8,1%. Un 40,6% han sido de estadio I y un 59,4% de estadio II, destacando el sacro como localización más frecuente. El valor del coeficiente alfa de Cronbach en las valoraciones consideradas ha indicado una fiabilidad de buena a moderada. En las 3 valoraciones realizadas un punto de corte de 12 se presentó como óptimo en la valoración del primer y segundo días de ingreso. En relación a la valoración del día con puntuación mínima, el punto de corte óptimo fue 10.

ConclusionesLa escala de Braden muestra una insuficiente validez predictiva y pobre precisión tanto para un punto de corte de 18 como de 16, que son los aceptados en los distintos escenarios clínicos.

Patients admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) usually present the failure of one or more organs or systems, or even multiorgan failure (MOF), and often require life support measures such as mechanical ventilation, continuous sedation, vasoactive medication and a range of devices including catheter, drains and tubes, as well as immobilization. Such measures have a significant negative impact upon one of the main mechanisms for preserving skin integrity–mobility–leaving patients highly vulnerable to the development of pressure ulcers (PUs).1,2 In this regard, although PUs can be found in many healthcare settings, they are particularly relevant in the ICU, with incidences ranging widely between 3.3% and 52.9%.3,4 Pressure ulcers are not recognized as an actual cause of mortality during hospital admission, though they are associated to both mortality and to other complications in patient recovery, with an increased risk of infection, in-hospital malnutrition, prolonged stay, increased nursing care burden, and healthcare cost increments.5

The identification of patients at risk is essential for the correct implementation of preventive programs and adequate resource utilization. In this regard, different risk assessment scales have been developed with the aim of helping healthcare professionals to identify individual risks for the development of PUs.6

A risk assessment scale should be able to distinguish between patients with and without a risk of suffering PUs. Validated risk assessment tools are recommended, in this respect, though it is not clear which tool is best suited to a concrete healthcare setting.7

At present, only 7 scales have been validated for use in the ICU. Three of them have been specifically developed for application in critical patients (Cubbin–Jackson, Norton Mod. Bienstein and Jackson–Cubbin), while the remaining four are of a more general nature (Norton, Waterlow, Braden and Braden Mod Song-Choi).8

The greatest efforts to analyze the risk factors underlying PUs have undoubtedly been made by Barbara Braden and Nancy Bergstrom, who were the first (and to date the only) authors to develop a conceptual map of the development of PUs. The Braden scale was developed in 1985 in the United States, in the context of a research project in sociosanitary centers, with the aim of resolving some of the limitations of the Norton scale. The authors developed their scale based on a conceptual scheme in which they compiled, ordered and related the existing knowledge of PUs.9,10 The Braden scale consists of 6 subscales: sensory perception, skin exposure to humidity, physical activity, mobility, nutrition and the hazard posed by friction and/or shear forces. It is a negative scale, i.e., the lower the score, the higher the corresponding risk, with a range of between 6 and 23 points. Patients at risk are defined by a score of ≤18, and are in turn subclassified as: very high risk (≤9 points), high risk (10–12 points), moderate risk (13–14 points) and low risk (15–18 points).11

In their initial study, Bergstrom et al.10 reported a sensitivity of 83% and a specificity of 64% for a cut-off point of 16. Fifteen years later, the same authors recommended a cut-off point of 18 as being more appropriate, as it allowed the inclusion of older and physiologically more unstable individuals of both Caucasian and Afro-American origin.12 However, this optimized cut-off point might not be the best option in all clinical settings, due to differences in patient characteristics and risk factors. The present study was designed to contribute to the validation of the Braden scale in patients admitted to an ICU, based on the analysis of its reliability and predictive validity.

Material and methodsA prospective, longitudinal, observational analytical study was carried out. The study population consisted of patients admitted to an adult ICU in a general third-level hospital. The ICU has 72 beds, of which 10 correspond to an intermediate care unit. Data collection was carried out in two phases. The first phase, with a duration of 31 days, started on 9 February 2015 and ended on 12 March 2015. The second phase, with a duration of 32 days, started on 30 May 2015 and ended on 30 June of that same year. The study included patients aged 18 years or older and admitted to the Unit for more than 24h. Patients with PUs at the time of admission were excluded, as were those admitted to the intermediate care unit. Patients requiring readmission were regarded as new cases. Patients were monitored until the time of appearance of the first PU or until the time of discharge or death. In the event of appearance of PUs, the patients were further monitored in case they developed a new ulcer, with evaluation of the course of already established ulcers.

With regard to the sample size, in order to secure a precision of 3% in the estimation of a proportion by means of a normal asymptotic confidence interval with two-tailed 95% finite population correction, and assuming an expected incidence of PUs in the general population of 8% (as this has been the mean incidence over the last 5 years), with a total population in this ICU registering a stay of over 24h of 1800 patients a year, it would be necessary to include 268 experimental units in the study. Taking into account an expected loss rate of 15%, we considered it necessary to recruit 316 experimental units in the study.

Data collectionThe data were collected daily by 5 investigating nurses through direct observation. The appearance of PUs was recorded in the patient history, along with the corresponding details (date of appearance, stage, location and outcome). Use was made of the four-stage PU classification and staging system recommended by the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) and the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP).13 The confirmation of PU grade was based on the opinion of a second investigating nurse, in order to establish the final diagnosis. The Braden scale was used to assess the risk of appearance of PUs. A score of >18 points was considered to indicate no risk of PU; 15–18 points was indicative of mild risk; 13–14 points was indicative of moderate risk; 10–12 points was indicative of high risk; and ≤9 was considered indicative of very high risk. In accordance to this risk, we applied the preventive measures contemplated in the PU prevention protocol of our ICU. Each patient was evaluated daily until the end of the monitoring period. In a first phase, we considered the following parameters for the analysis of reliability and validity: the score in the first 24h of admission, the score on the second day of admission, and the minimum score obtained during patient stay in the ICU. In a second phase, we repeated the analysis of reliability and validity, with the exclusion of stage I PUs.

Variables and instrumentsThe primary or dependent variable was the appearance during patient admission of PUs in stages or categories from I to IV, and in any body location. The additional categories for the United States were not considered.

Three categories were established for the rest of the variables:

- 1.

Demographic: age and gender.

- 2.

Clinical: duration of stay in the ICU, patient origin, readmission or no readmission, comorbidities, diagnosis upon admission, nursing care burden measured with the Nursing Activities Score (NAS), complications and outcome variables (limitation of therapeutic effort [LTE], death).

- 3.

Prognostic: daily PU risk score based on the Braden scale and SAPS 3 score upon admission as severity indicator.

The project was carried out following the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki regarding the ethical principles for the conduction of medical research in human subjects.

All records and questionnaires were kept by the principal investigator. Patient identification was limited to the assigned case number, thereby complying with Spanish legislation referred to personal data protection (Organic Act 15/1999 of 13 December).

Authorization to carry out the study was requested from the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Andalusia, which did not consider it necessary to obtain patient informed consent, since no interventions of any kind were contemplated in the study.

Statistical analysisAn exploratory analysis of the data was carried out to identify extreme values and characterize differences between subgroups of individuals, as well as to detect alterations in quantitative variables in order to establish possible breaches in the statistical assumptions. A descriptive analysis of the sample was then made. Numerical variables were reported as the mean and standard deviation (SD) in the case of those parameters with a normal distribution, and as the median and quartiles in the case of parameters with a non-normal distribution. Qualitative variables in turn were reported as absolute frequencies and percentages.

Incidence was calculated as cumulative incidence. The incidence rate or incidence density was calculated as the ratio between the number of PUs occurring in the course of admission to the ICU and the sum of the periods of stay in the ICU of each of the individuals in the course of the study period per 1000 days of stay.

A bivariate inferential analysis was carried out to compare quantitative/numerical variables between patients who developed ulcers and those who did not. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used, since normality of the quantitative variables could not be assumed. Likewise, the relationship between qualitative variables in the two groups was explored using the chi-squared test or the Fisher exact test. The corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were also calculated.

In order to check the reliability of the items that conform the Braden scale, we analyzed its internal consistency in the study sample based on the Cronbach alpha coefficient. The Spearman correlation coefficient (rs) was used to determine the subscales exhibiting the greatest correlation to total risk obtained from the Braden scale, while the coefficient of determination (rs2) was used to establish the percentage variability of the Braden scale explained by each of the subscales.

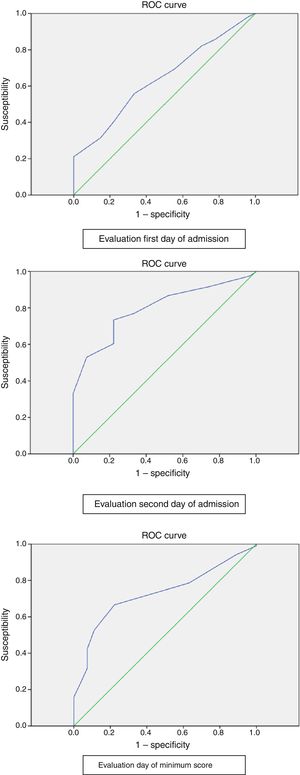

Analysis of the validity of the scale was based on the calculation of sensitivity, specificity, efficacy or accuracy, the positive predictive value, the negative predictive value, and the likelihood ratio. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted, with calculation of the area under the curve (AUC).

Data analysis was carried out using the IBM SPSS version 20.0 statistical package for MS Windows.

ResultsThe study sample consisted of 335 patients. A total of 154 patients were not included, since their stay in the ICU was less than 24h. Fifteen patients were excluded due to the presence of PUs at the time of admission. The mean patient age was 59.76 years (SD±14.30), and 61.5% were males. The median ICU stay was four days (p25=2.0; p75=4.0).

Of the 335 included patients, 27 developed PUs. The PU incidence rate was therefore 8.1%. Three of these patients developed two PUs, while one developed three ulcers. A total of 32 PUs was therefore recorded. On expressing incidence as the incidence rate corresponding to patients who developed PUs, the result was 11.72 per 1000 days of stay (95%CI: 7.88–16.82).

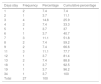

With regard to stage, 13 PUs (40.6%) corresponded to stage I and 19 (59.4%) to stage II. There were no stage III or IV ulcers. The PUs had multiple locations (see Table 1), with the sacrum being the most frequently affected zone (n=19; 59.4%). The median time to appearance of the ulcers was 7 days (p25=3.5; p75=11), with a range of 1–34 days. Most of the ulcers (88.9%) appeared in the first 14 days of admission to the Unit. The frequency and percentage distributions are shown in Table 2. Only one patient was classified as presenting no ulcer risk at the evaluation made in the first 24h (Table 3). At evaluation on the second day of admission, of the 27 patients who developed PUs, 6 were classified as mild risk, 14 as high risk and 7 as very high risk cases. On the day of the minimum score, one patient was classified as mild risk, one as moderate risk, 15 as high risk, and 10 as very high risk.

Time of appearance of the pressure ulcers.

| Days stay | Frequency | Percentage | Cumulative percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 7.4 | 7.4 |

| 2 | 1 | 3.7 | 11.1 |

| 3 | 4 | 14.8 | 25.9 |

| 4 | 2 | 7.4 | 33.3 |

| 5 | 1 | 3.7 | 37 |

| 6 | 1 | 3.7 | 40.7 |

| 7 | 3 | 11.1 | 51.8 |

| 8 | 2 | 7.4 | 59.2 |

| 9 | 2 | 7.4 | 66.6 |

| 11 | 3 | 11.1 | 77.7 |

| 12 | 1 | 3.7 | 81.4 |

| 13 | 2 | 7.4 | 88.8 |

| 18 | 1 | 3.7 | 92.5 |

| 19 | 1 | 3.7 | 96.2 |

| 34 | 1 | 3.7 | 100 |

| Total | 27 | 100 |

Classification of pressure ulcer (PU) risk on the first day of admission and development of PUs.

| Frequency | Percentage | Cumulative percentage | Appearance of PUs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||||

| No risk (>18) | 1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1 | 0 |

| Mild (15–18) | 100 | 29.9 | 30.2 | 96 | 4 |

| Moderate (13–14) | 80 | 23.9 | 54.1 | 75 | 5 |

| High (10–12) | 104 | 31 | 85.1 | 92 | 12 |

| Very high (≤9) | 50 | 14.9 | 100 | 44 | 6 |

| Total | 335 | 100 | 308 | 27 | |

Table 4 shows the independent variables seen to be significantly associated to the development of PUs in the univariate analysis.

Comparison of variables in patients who developed pressure ulcers (PUs) and those who did not.

| Total (n=335) | Patients without PUs (n=308) | Patients with PUs (n=27) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 59.76±.30 | 59.41±14.11 | 63.74±16.12 | 0.036 |

| Male gender | 61.5% | 59.7% | 81.5% | 0.026 |

| Origin | 0.001 | |||

| Ward/other hospital | 24.8% | 22.4% | 51.9% | |

| Emergency/operating room | 75.2% | 77.6% | 48.1% | |

| Comorbidity: diabetes | 20.3% | 18.8% | 37% | 0.024 |

| Duration of stay in ICU | 4.0 (2.0–8.0) | 4.0 (2.0–7.0) | 13.0 (8.0–25.0) | <0.001 |

| SAPS 3 (severity and prognosis) | 56.0 (45.0–68.0) | 54.0 (44.0–66.0) | 74.0 (62.0–83.0) | 0.000 |

| Risk of PU Braden scale | 13.0 (11.0–15.0) | 13.0 (11.0–15.0) | 12.0 (10.0–13.0) | 0.015 |

| Complications | 32.2% | 27.6% | 85.2% | <0.001 |

| Outcome variables | ||||

| LTE | 7.5% | 6.5% | 18.5% | 0.023 |

| Death | 13.7% | 12.7% | 25.9% | 0.055 |

In order to assess the reliability of the items that conform the Braden scale, we examined the internal consistency of the scale in our sample of patients, using the Cronbach alpha coefficient,14,15 which allowed us to quantify the degree of partial correlation of the items, i.e., the degree to which the items of the construct were related. The Cronbach alpha coefficient in the assessment made in the first 24h was 0.443, which indicates moderate correlation between the items. On the second day of admission the coefficient increased to 0.722, which indicates good reliability, with a strong correlation between the items. In turn, on the day of the lowest score, the Cronbach alpha coefficient was 0.561, indicative of moderate reliability. In a second phase, with the exclusion of stage I PUs, the Cronbach alpha coefficient in the assessment made in the first 24h was 0.425, which indicates moderate correlation between the items. On the second day of admission the coefficient increased to 0.690, which indicates good reliability, with a strong correlation between the items. In turn, on the day of the lowest score, the Cronbach alpha coefficient was 0.543, indicative of moderate reliability.

The subscales showing the greatest correlation to total risk as determined by the Braden scale (i.e., the subscales to which the risk observed in our sample was fundamentally attributable) were sensory perception, mobility and friction/shear forces at all three evaluations, considering all the ulcer stages and also after excluding stage I ulcers. The Spearman correlation coefficient (rs) was used to calculate these correlations.

Based on the coefficient of determination (rs2), we determined the percentage of variability of the Braden scale explained by each of the subscales (Table 5 shows both the correlation coefficients and coefficients of determination according to the day of observation). At evaluation on the first day of admission, 64% of the variability of the Braden scale was explained by sensory perception, 60.3% by mobility and 36.9% by friction/shear forces. At evaluation on the second day of admission, 70.8% of the variability of the Braden scale was explained by sensory perception, 67% by mobility and 37.3% by friction/shear forces. Lastly, on the day of the minimum score, 68.3% of the variability of the Braden scale was explained by sensory perception, 61.1% by mobility and 41% by friction/shear forces. Very similar values were recorded after excluding the stage I PUs.

Correlation coefficients and coefficients of determination with the Braden scale according to the day of the observation.

| Day of observation | Braden scale: subscales | Spearman correlation coefficient (rs) | Coefficient of determination (rs2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| First day of admission | Sensory perception | 0.800 | 0.640 |

| Humidity | 0.195 | 0.038 | |

| Activity | 0.087 | 0.0075 | |

| Mobility | 0.777 | 0.603 | |

| Nutrition | 0.431 | 0.185 | |

| Friction/shear forces | 0.608 | 0.369 | |

| Second day of admission | Sensory perception | 0.842 | 0.708 |

| Humidity | 0.330 | 0.108 | |

| Activity | 0.369 | 0.136 | |

| Mobility | 0.819 | 0.670 | |

| Nutrition | 0.611 | 0.373 | |

| Friction/shear forces | 0.779 | 0.606 | |

| Day of minimum score | Sensory perception | 0.827 | 0.683 |

| Humidity | 0.291 | 0.084 | |

| Activity | 0.091 | 0.008 | |

| Mobility | 0.782 | 0.611 | |

| Nutrition | 0.552 | 0.304 | |

| Friction/shear forces | 0.641 | 0.410 | |

| Exclusion of stage I PUs | |||

| First day of admission | Sensory perception | 0.798 | 0.636 |

| Humidity | 0.203 | 0.041 | |

| Activity | 0.087 | 0.0075 | |

| Mobility | 0.779 | 0.606 | |

| Nutrition | 0.425 | 0.180 | |

| Friction/shear forces | 0.603 | 0.363 | |

| Second day of admission | Sensory perception | 0.835 | 0.697 |

| Humidity | 0.339 | 0.114 | |

| Activity | 0.371 | 0.137 | |

| Mobility | 0.816 | 0.665 | |

| Nutrition | 0.609 | 0.370 | |

| Friction/shear forces | 0.771 | 0.594 | |

| Day of minimum score | Sensory perception | 0.821 | 0.674 |

| Humidity | 0.324 | 0.104 | |

| Activity | 0.081 | 0.0065 | |

| Mobility | 0.789 | 0.622 | |

| Nutrition | 0.528 | 0.278 | |

| Friction/shear forces | 0.656 | 0.430 | |

With regard to validity and predictive capacity (Table 6), a cut-off point of 12 was found to be optimum, as it offered the best balance between sensitivity and specificity at evaluation on the first and second days of admission–sensitivity and specificity being 66.7% and 55.8%, respectively, on the first day of admission, and 77.8% and 73.4% on the second day of admission. With regard to evaluation on the day of the minimum score, the optimum cut-off point was identified as 10, with a sensitivity of 77.8% and a specificity of 66.6%. On excluding the stage I ulcers, a cut-off point of 12 was seen to be optimum, as it offered the best balance between sensitivity and specificity at evaluation on the first day of admission–sensitivity and specificity being 70.6% and 55.8%, respectively. A cut-off point of 11 in turn was seen to be optimum on the second day of admission, with a sensitivity of 82.4% and a specificity of 76.9%. Finally, with regard to evaluation on the day of the minimum score, the optimum cut-off point was identified as 10, with a sensitivity of 82.4% and a specificity of 66.6%.

Predictive validity of the Braden scale according to the day of observation.

| Day of observation | Cut-off point | Sensitivity 95%CI | Specificity 95%CI | PPV 95%CI | NPV 95%CI | LR+ 95%CI | LR− 95%CI | Accuracy 95%CI | AUC 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First day of admission | 12 | 66.7% (47.8–81.4) | 55.8% (50.3–61.3) | 11.7% (7.5–17.7) | 95% (90.8–97.4) | 1.51 (1.12–2.03) | 0.60 (0.34–1.04) | 56.7% (51.4–61.9) | 66.8% (57.6–76.0) |

| Second day of admission | 12 | 77.8% (59.2–89.4) | 73.4% (68.2–78.0) | 20.4% (13.7–29.2) | 97.4% (94.5–98.8) | 2.92 (2.22–3.84) | 0.30 (0.15–0.62) | 73.7% (68.8–78.2) | 79.5% (72.6–86.4) |

| Day of minimum score | 10 | 77.8% (59.2–89.4) | 66.6% (61.1–71.6) | 16.9% (11.4–24.5) | 97.2% (93.9–98.7) | 2.33 (1.80–3.00) | 0.33 (0.16–0.68) | 67.5% (62.3–72.3) | 72.8% (65.0–80.7) |

| Exclusion of stage I PUs | |||||||||

| First day of admission | 12 | 70.6% (46.9–86.7) | 55.8% (50.3–61.3) | 8.1% (4.7–13.6) | 97.2% (93.6–98.8) | 1.60 (1.52–2.23) | 0.53 (0.25–1.12) | 56.6% (51.2–61.9) | 65.6% (53.8–77.4) |

| Second day of admission | 11 | 82.4% (59.0–93.8) | 76.9% (71.9–81.3) | 16.5% (10.1–25.8) | 98.8% (96.4–99.6) | 3.57 (2.65–4.82) | 0.23 (0.08–0.64) | 77.2% (72.4–81.5) | 81.9% (74.1–89.8) |

| Day of minimum score | 10 | 82.4% (59.0–93.8) | 66.6% (61.1–71.6) | 12.0% (7.3–19.1) | 98.6% (95.8–99.5) | 2.46 (1.88–3.23) | 0.27 (0.09–0.75) | 67.4% (62.1–72.3) | 73.2% (64.2–82.2) |

AUC: area under the ROC curve; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; LR+: positive likelihood ratio; LR−: negative likelihood ratio; NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value.

Fig. 1 shows the areas under the ROC curves. The analysis of AUC revealed moderate discriminating capacity (66.8%) at evaluation on the first day of admission and on the day of the minimum score (72.8%), with good discriminating capacity (79.5%) at evaluation on the second day of admission. Very similar values were recorded after excluding the stage I PUs.

DiscussionThe incidence of PUs recorded in our ICU (8.1%) is lower than the rates reported by other authors in similar clinical settings. Only Tescher et al.3 recorded a lower incidence (3.3%); however, these authors did not include stage I PUs, due to their reversible nature, and moreover included individuals from 10 ICUs and 7 intermediate care units. In our study, 40.6% of the ulcers corresponded to stage I, and we moreover did not include patients admitted to the intermediate care unit. The mentioned findings could be attributable to the fact that nursing staff training and sensitization result in a high tendency to report both the risk and appearance of PUs. In effect, our Unit has adopted a PU prevention protocol comprising the systematic evaluation of ulcer risk based on the Braden scale, which allows nurses to quickly introduce a series of preventive measures adjusted to the detected risk level. These measures are those recommended by the GNEAUPP in its general guidelines on the management of PUs.16 Brunet and Kurcgant17 published the incidence of PUs before and after the implementation of a prevention protocol. The latter was established in order to identify patients at risk of developing PUs and introduce preventive measures that were clearly contemplated in the protocol. The authors documented an important decrease in ulceration rate from 41.02% before the protocol to 23.1% after its implementation.

In the present study, of the 27 patients with PUs, 23 developed one ulcer (85.1%), three developed two ulcers (11.1%), and one developed three PUs (3.7%). In all the reviewed studies, most patients developed a single PU. In the study published by Campanili et al.,18 100% of the patients developed a single ulcer. Data similar to those of our own study were published by Tayyib et al.,19 who documented one ulcer in 81.8% of the patients, two ulcers in 12.1%, and three PUs in 6.1%. The most commonly affected location was the sacral zone (59.4%). In the study carried out by Oliveira et al.,4 the incidence of PUs in the sacral zone was 65.8%, versus 61% in the study of Catala et al.20 and 60% in the study published by Matos et al.21 Of note is the study of Roca-Biosca et al.,22 where PUs of the face (ears, nose and mouth), caused by medical devices, and sacral ulcers (ischium, buttocks and sacral zone) showed the same frequency (31.6%).

At present, we are working in the ICU with instruments for assessing PU risk that have not been specifically developed for this concrete clinical setting. As a result, they might not be adequate, since they do not take into account risk factors that are practically exclusive of the ICU.23 With regard to the evaluation of ulcer risk based on the Braden scale in our setting, 99.7% of the patients were classified as presenting PU risk in the first 24h after admission to the Unit. Of these subjects, 29.9% presented mild risk, 23.9% moderate risk, 31% high risk, and 14.9% very high risk. A total of 307 patients (91.6%) were considered to be at risk, but did not develop PUs. All the patients that did develop PUs were classified as being at risk. In the investigation carried out by Slowikowski and Funk,24 almost 60% of the patients were classified as presenting high or very high ulcer risk, while 29.8% presented moderate risk, 10% low risk, and only two patients were considered to have no ulcer risk (0.5%). Thus, 99.5% of the patients were classified as being at risk of developing PUs. In the study published by Cremasco et al.,25 98.7% of the patients were classified with PU risk from the time of admission, while in the sample of Brunet and Kurcgant,17 99.1% of the patients were classified as being at risk of developing PUs.

On the basis of these studies it can be concluded that between 75% and 90% of the patients were classified as being at risk of developing PUs, but finally did not develop ulcers. Application of the Braden scale over-predicts the risk of PUs, thus making it difficult to draw conclusions regarding its true predictive capacity. Indeed, if this scale predicts that almost 100% of all patients in the ICU setting are at risk of developing PUs, potentially unnecessary preventive measures may be adopted–resulting in excessive healthcare costs and inefficient use of professional working time. On the other hand, it could be postulated that thanks to the adoption of such preventive measures–which the professionals know to be important–not all patients at risk of developing PUs actually develop ulcers.

In our study, the Braden items or subscales that showed the greatest correlation to the total risk score (i.e., those items or subscales to which the risk observed in our sample was largely attributable) were sensory perception, mobility and friction/shear forces. There was no significant difference in relation to the activity subscale between the patients who developed PUs and those who did not. This observation is consistent with the data reported by earlier studies in the intensive care setting. Most of the patients in this setting are bedridden and show little variation in their level of activity. In the study published by Cox,26 out of the 6 subscales, only mobility and friction/shear forces were identified as significant predictors of PUs. Although the evidence confirms that the Braden score acts as a predictor of PUs in critical patients, the investigations on the contribution of the scores of the different subscales have been limited, and the results have been inconclusive.

In our study, the Braden score corresponding to the first day of admission showed very high sensitivity for a cut-off point of 18 (100%), though specificity was very low (0.3%), in the same way as the positive predictive value (8.1%). For a cut-off point of 16, sensitivity was 100%, specificity 7.8%, and the positive predictive value 8.7%. Similar results were obtained on applying the scale on the second day of admission and on the day of the minimum score. These values, for both cut-off points, suggest a high proportion of false-positive results. A cut-off point of 12 afforded the best balance between sensitivity and specificity, and in positive predictive value and negative predictive value, on occasion of the evaluations on the first and second day of admission. In the study carried out by Hyun et al.27 in three ICUs (two medical and one surgical Unit), the optimum cut-off point was found to be 13, which is similar to the value established in our own study. Serpa et al.28 likewise identified an optimum cut-off point of 12 on occasion of the evaluation on the first day of admission, and of 13 on occasion of the subsequent evaluations.

The analysis of the AUC revealed moderate discriminating capacity (66.8%) for evaluation on the first day of admission and on the day of the minimum score (72.8%), with good discriminating capacity (79.5%) for evaluation on the second day of admission. In the case of the previously mentioned study by Hyun et al.,27 the AUC was 67.2% for a cut-off point of 13, while Serpa et al.28 recorded an AUC of 77.8% on occasion of the evaluation on the first day, and of 77.9% on the third day.

ConclusionsThe recorded incidence of PUs in our series was 8.1%. Expressed as incidence rate, the result was 11.72 per 1000 days of stay. A total of 40.6% of the ulcers corresponded to stage I and 59.4% to stage II, with the sacrum being the most frequently affected zone. With regard to reliability, at evaluation on the second day of admission, the Cronbach alpha coefficient was 0.722, which is indicative of good reliability, though the latter was only seen to be moderate on occasion of the rest of the evaluations. In the present study, a cut-off point of 12 with an AUC of 79.5% at evaluation on the second day of admission yielded the best predictive value in our critical care setting. On excluding stage I ulcers, a cut-off point of 11 with an AUC of 81.9% at evaluation on the second day of admission yielded the best predictive value. It can be concluded that the Braden scale in our investigation showed insufficient predictive validity and poor precision, discriminating patients at risk of developing PUs with cut-off points of both 18 and 16, which are those accepted in the different clinical scenarios.

Authors’ contributionMarta Lima-Serrano performed the statistical analysis and interpretation of the data, with critical review of the manuscript, and approved the final version for publication.

M. Isabel González-Méndez designed the study, supervised its correct implementation, drafted the manuscript, and approved the final version for publication.

Inmaculada Alonso-Araujo participated in data acquisition, with critical review of the manuscript, and approved the final version for publication.

Catalina Martín-Castaño participated in data acquisition, with critical review of the manuscript, and approved the final version for publication.

Joaquin Salvador Lima-Rodriguez participated in the design of the investigation and in interpretation of the data, with critical review of the manuscript, and approved the final version for publication.

Financial supportThe authors declare that no financial support of any kind was received for carrying out the study or for preparing the article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no financial or personal conflicts with other persons or organizations capable of having an inadequate influence upon their work.

Please cite this article as: Lima-Serrano M, González-Méndez MI, Martín-Castaño C, Alonso-Araujo I, Lima-Rodríguez JS. Validez predictiva y fiabilidad de la escala de Braden para valoración del riesgo de úlceras por presión en una unidad de cuidados intensivos. Med Intensiva. 2018;42:82–91.